This year, on 26 January, no doubt many people around Australia will gather to cook at the BBQ and swim in the surf. Families and friends will enjoy a relaxing time on a public holiday. Somewhere in the background, perhaps, there will hover a sense of satisfaction that we are “the lucky country” full of “mates and cobbers”, where there is “a fair go” for everyone, a country in which we can wave our flags, have our BBQs, kick back and relax.

Indeed, around the world, people who call Australia home will most likely be gathering, perhaps with fellow-Aussies, to celebrate the day. I know that when I was living in a foreign country, 40 years ago, I did just that—finding some other Australians in the university’s Graduate Student Housing to share in a meal as we celebrated “being Australian” in a foreign land.

That was all almost half-a-lifetime ago, now; and my perspective on this has changed somewhat, I confess. I am still, as I was then, a fervent republican, believing that Australia needs to be a completely independent nation with no role at all for the inbred imperialist family whose forbears colonised this continent and who still have a formal, legal role in the affairs of this country, from many thousands of kilometres away.

And I am still resolutely opposed to the primitive tribal tendencies inherent in nationalism, and its ugly cousin jingoism, because of the emotional damage that this does to impressionable minds, and the consequent savagery that it has unleashed in warfare across the years.

The cost of war is immense and long-enduring; the “victory” won by a nation in prosecuting war is fleeting by comparison. War means injury and death, to our own troops, and to the troops of those we are fighting against. Every death means a family and a local community that is grieving. There is great emotional cost just in one death, let alone the thousands and thousands that wars incur. To say nothing of the damage done to civilians, particularly women and children, as “collateral damage” in these nationalistic enterprises. Jingoistic nationalism fuels the appetite for warfare.

So it is with some small degree of satisfaction that I note that the many congregations of the Uniting Church of have held a Day of Mourning to reflect on the dispossession of Australia’s First Peoples and the ongoing injustices faced by First Nations people in this land. This resets and reorients the focus of the time around the “national day” of Australia.

For those of us who are Second Peoples from many lands, this focus offers an opportunity to lament that we were and remain complicit in the ongoing consequences of this dispossession. It also invites us to consider what we might do to move away from that negative trajectory.

The observance of a Day of Mourning on the Sunday before 26 January arises from a request from the Uniting Aboriginal and Islander Christian Congress (UAICC) which was endorsed by the 15th Assembly in 2018. Since then, many Congregations have held worship services that reflect on the effects of invasion, colonisation and racism on First Peoples. (This year it took place on Sunday 21 January.)

The first Day of Mourning took place in 1938, after years of work by the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) and the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA). In a pamphlet published for the occasion, it was stated that “the 26th of January, 1938, is not a day of rejoicing for Australia’s Aborigines; it is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years’ so-called “progress” in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country.”

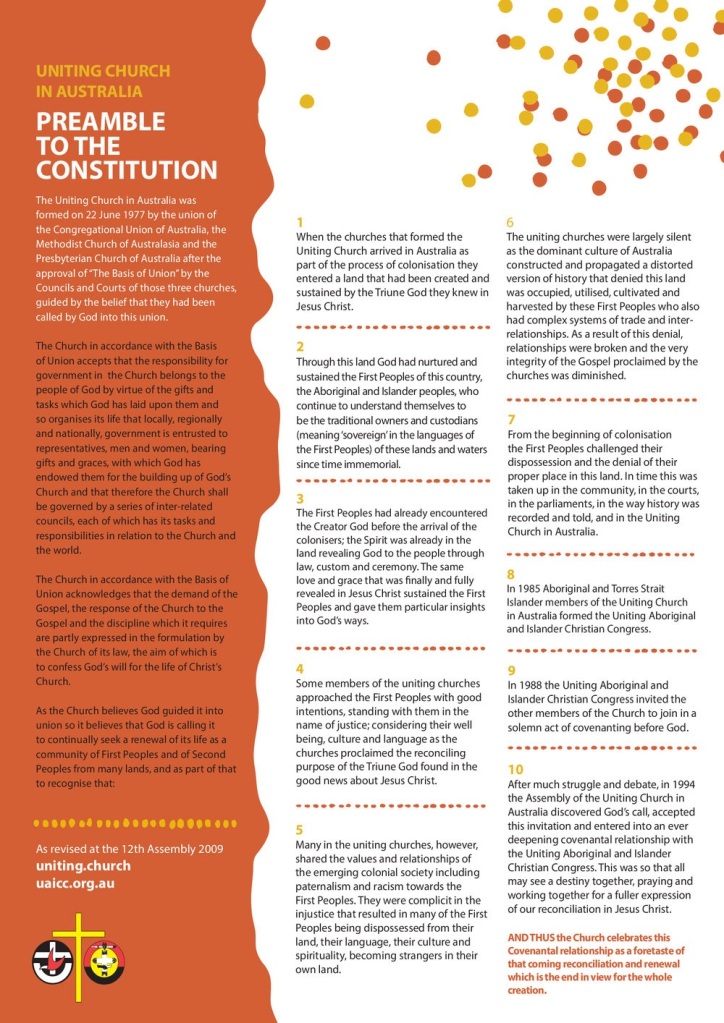

The Uniting Church has acknowledged that our predecessors in the denominations which joined in 1977 to form the Uniting Church have been “complicit in the injustice that resulted in many of the First Peoples being dispossessed from their land, their language, their culture and spirituality, becoming strangers in their own land”. That itself is a cause for lament and mourning.

The Uniting Church has also recognised that people in these churches “were largely silent as the dominant culture of Australia constructed and propagated a distorted version of history that denied this land was occupied, utilised, cultivated and harvested by these First Peoples who also had complex systems of trade and inter-relationships”.

[The quotations above come from the Revised Preamble to the Constitution of the Uniting Church in Australia, adopted in 2009]

See https://ucaassembly.recollect.net.au/nodes/view/442

In worship resources prepared in relation to this Revised Preamble, people are invited to affirm the general belief that “the Spirit has been alive and active in every race and culture, getting hearts and minds ready for the good news: the good news of God’s love and grace that Jesus Christ revealed”, as well as the specific statement four our context, that “from the beginning the Spirit was alive and active, revealing God through the law, custom and ceremony of the First Peoples of this ancient land”.

People are also invited to confess “with sorrow the way in which their land was taken from them and their language, culture and spirituality despised and suppressed”, as well as the reality that “in our own time the injustice and abuse has continued; we have been indifferent when we should have been outraged, we have been apathetic when we should have been active, we have been silent when we should have spoken out.”

So on 26 January this year, as a nation of multicultural complexity, with diverse narratives of origins and developments over the years, we would do well to follow this lead, and ensure that what happens on this day might include realistic mourning for what has been done in past years, and for what this means in our own time for First Peoples of this country; and perhaps some indications as to how we are planning and working to rectify injustice and overturn oppression.

Alongside the celebration of the ways that Australia has become a vibrant, strengthened “modern nation”, we would do well to include this note of reality and expression of hope for those who have, unfairly and in a disproportionate way, shouldered the burden of inequity over the decades.

It would be good for the trite, simplistic, jingoistic approach to our national day to incorporate some maturity in how we think about, reflect upon, and commit to act in relation to First Peoples. The sorry saga of last year’s referendum should at least prod us in this direction, surely?