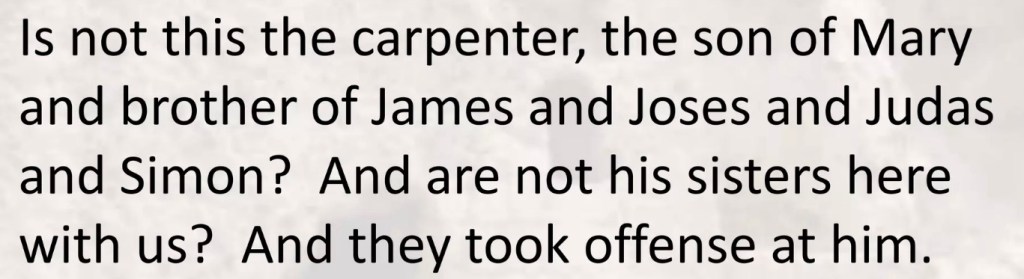

The offering from the narrative lectionary this coming Sunday (Mark 6:1–29) begins with the scene where Jesus goes to the synagogue in his hometown, Nazareth (6:1–6) and is rejected by those who “took offence at him” (6:3). Although he spoke with wisdom and performed acts of power (6:2), he is scorned as merely “the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon … and his sisters, here with us” (6:3).

You can imagine the murmurs amongst the people of the town. “He was not the eloquent preacher. Not the erudite teacher. Not the compassionate healer. Not the dazzling miracle-worker. Just plain old Jesus, the carpenter, from a local family. Nothing to look at here. Nothing of importance. A nobody, really. But he has pretensions. And we can’t stand for that, can we?”

Perhaps I’m being a little harsh on the townsfolk? Perhaps there is more to Jesus than they recognised, and perhaps Mark’s narrative might indicate that it is not wise to stereotype Jesus, as they were doing?

Earlier in his narrative, Mark has told of an encounter that Jesus had with his family when he came out of a house in Capernaum (3:20). Some onlookers in Capernaum describe him as being “out of his mind” (ἐξέστη, 3:21). This is a term that literally means that he was “standing outside of himself”, as if in a kind of dissociative state. It may be that this was the reason that Jesus was returning to his family?

The encounter doesn’t go well, however. Scribes have come from Jerusalem. They have already been antagonistic towards Jesus, questioning whether Jesus was blaspheming (2:6–7), and casting doubts on his choice of dinner guests (“why does he eat with tax collectors and sinners.”, 2:16). There will be further disputation with scribes (7:1–5; 9:14; 12:28, 38–41) and they will be implicated in the plot to arrest Jesus (11:18, 27; 14:1, 43, 53; 15:1) and in his death (8:31; 10:33).

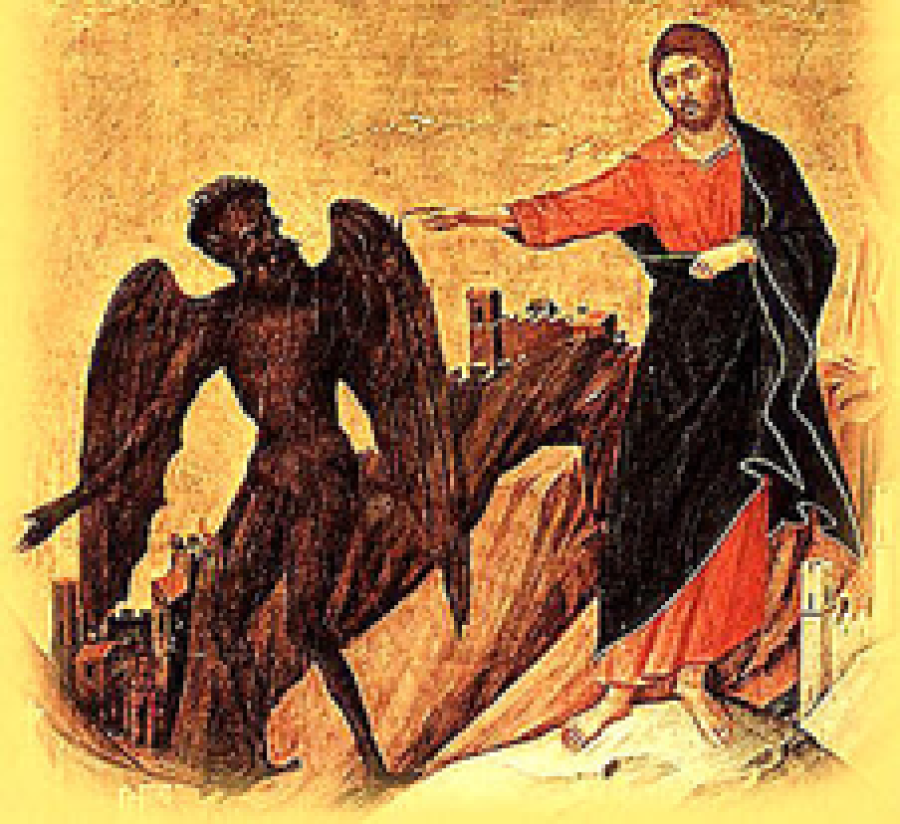

These scribes—hardly friends—articulate what others present may well have been thinking: “he has Beelzebul” (3:22). The charge of demon possession correlates with the accusation levelled at John 10:20. It appears to have been one way that Jesus was stereotyped by others.

Beelzebul (Βεελζεβοὺλ), “the ruler of the demons”, is known from earlier scriptural references to Baal-zebub in 1 Kings 1:2–6, 16, where he is described as “the god of Ekron”, a Philistine deity. There is scholarly speculation that Beelzebul may have meant “lord of the temple” or “lord of the dwelling”, from the Hebrew term for dwelling or temple (as found at Isa 63.15 and 1 Kings 8.13); or perhaps it was connected with the Ugaritic word zbl, meaning prince, ruler.

Jesus refutes the charge in typical form, by telling a parable (3:23–27) that ends with the punchline about “binding the strong man” (τὸν ἰσχυρὸν δήσῃ). This potent phrase encapsulates something that sits right at the heart of the activities of Jesus in Galilee—when he encounters people who are possessed by demons, and when he casts out those demons, he is, in effect “binding the strong man”.

The notion that a demon would bind the person that they inhabited is found at Luke 13:16, and in the book of Jubilees (5:6; 10:7-11). The book of the same title by Ched Myers provides a fine guide to reading the whole of Mark’s Gospel through this lens (see https://chedmyers.org/2013/12/05/blog-2013-12-05-binding-strong-man-25-years-old-month/)

The accusation that refers to “blasphemy against the Holy Spirit” (3:29) may well reflect the stereotype that Jesus was demon-possessed (3:30). That stereotyped view of Jesus cannot be allowed to stand, for it cannot be justified in any way—at least, in Mark’s view.

So we see that there was dispute about Jesus, even beyond his hometown of Nazareth. There were those who sought to stereotype him in a negative way.

So Jesus goes to his hometown, with his disciples, and participates in the local synagogue on the sabbath. What do we know of his status in his hometown?

“In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan” (Mark 1:9) is how Jesus is introduced in this Gospel. Mark takes us straight to the adult Jesus, bypassing the newborn infant who appears in other narratives. There is no explanation of his background; no stories from his childhood, to show the nature,of his character (such as were common in biographies written by educated folks in the Hellenistic world).

There is certainly no mention of Bethlehem, nor the rampage of Herod; nor any reference to magi travelling from the east, bearing gifts; nor to a census ordered under Quirinius, necessitating short-term accommodation. There is no story of the infant Jesus at all—and most strikingly, no mention of Mary and Joseph as the parents of Jesus in the opening scenes of this earliest Gospel.

Rather, in Mark’s narrative reporting the beginning of the good news about Jesus, the chosen one, Jesus explicitly distances himself from his family. “Who are my mother and my brothers?”, he asks, when confronted by scribes from Jerusalem and labelled as “out of his mind” by his own family (Mark 3:21, 33).

In this week’s passage, the people of his hometown (Nazareth) do not identify as “son of Joseph”—only in John’s book of signs do his fellow-Jews identify him as “son of Joseph” (John 6:42). So it is up to Luke and Matthew, each in their own way, to link Jesus, as a newborn, to these parents.

In Mark’s account of the scene when the adult Jesus returns to his hometown, he is “the carpenter, the son of Mary” (6:3). This is the only time that the name of his mother appears in this earliest account of Jesus; and there is simply no mention, by name, or by relationship, of his putative father. (Some scribes later modified this verse (Mark 6:3) to refer to him as “son of the carpenter and of Mary”, to align Mark’s account with how Matthew later reports it at Matt 13:55.)

Other than this one reference, Mark makes no reference to Jesus’s parents. He is simply, and consistently identified as “the son of God” (Mark 1:1; 3:11; 5:7; 9:7; 15:39). On one occasion, he is addressed as “son of David” (10:47–48; although this description is the subject of debate at 12:35–37).

More often, in this earliest of Gospels, using a term taken from Hebrew Scripture, Jesus refers to himself, or others refer to him, as “the son of humanity” (more traditionally translated as “the son of man”) (2:10, 28; 8:31, 38; 9:9, 12, 31; 10:33, 45; 13:26; 14:21, 41, 62; see Ezek 2:1, 8; 3:1, 4, 16; etc; and Dan 7:13). The origins and identity of Jesus, in Mark’s eyes, relate more to the larger picture—of his Jewish heritage, in his relationship to the divine, and with his role for all humanity—than to the immediacy of parental identification.

Mark ensures that we grasp this larger picture of Jesus in the way he presents Jesus. He also indicates that it is not proper to stereotype Jesus, describing him in demeaning terms, objectifying him as problematic or as “other”. It is a practice that we would do well to emulate in our relationships with others. And in considering Jesus, we should push beyond the stereotypes to discover the person who Jesus really is.