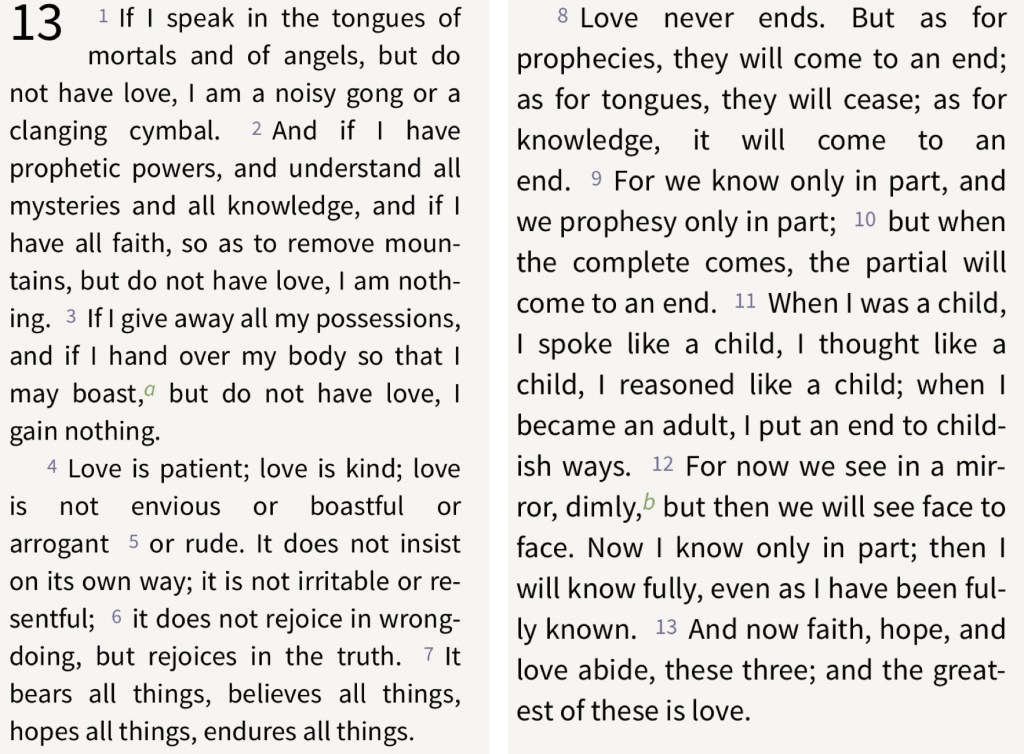

For the passage to be read and heard this coming Sunday, the Narrative Lectionary has proposed what is perhaps the most well-known part of Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians: the chapter on love (1 Cor 13:1–13). Paul waxes lyrical about love, telling the Corinthians that love “bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things; love never ends” (13:7–8), and builds to a wonderful rhetorical climax in which he affirms that “faith, hope, and love abide, these three; and the greatest of these is love” (13:13).

As well as being a rhetorical tour de force, and the most beloved part of this letter of Paul, this chapter is also, in my view, the most misunderstood and misused chapter of this letter—as I will attempt to explain below.

It is clear from Paul’s description that, when the community in Corinth gathered for worship, there was a high degree of disorder manifested. Paul devotes four chapters to this issue (11:1—14:40). Throughout this section of the letter, Paul writes with a single focus in mind; he writes to bring order and decency to this situation (14:40).

He begins his consideration of the disorder evident in the community by asserting the importance of maintaining “the traditions just as I handed them on to you” (11:2), reminding them of words that “I received from the Lord” and duly “handed on to you” (11:23). He instructs the Corinthians to seek to speak to others in worship “for their upbuilding and encouragement and consolation” (14:3).

He advises them to exercise their spiritual gifts appropriately; to “strive to excel in them for building up the church” (14:12), to “not be children in your thinking … but in thinking be adults” (14:20). He advises them, “let all things be done for building up” (14:26), noting that “all things should be done decently and in order” (14:40), for “God is a God not of disorder but of peace” (14:33).

The hymn in chapter 13 is an integral part of that overarching purpose. As well as his reminder of “the traditions just as I handed them on to you” (11:1), Paul asserts that they must acknowledge that “what I am writing to you is a command of the Lord” (14:37). He happily draws from various authorities; he alludes to scriptural ideas (11:3, 7–9, 10; 14:4), directly cites Hebrew scripture (14:21, 25), refers to the words of Jesus (11:24–25), claims the precedent of nature (11:14) and church custom (11:16), and in a controversial passage, refers to what takes place “in all the churches of the saints” (14:33b–34).

Chapter 12 contains an adaptation of an image which was extensively used in political discussions about the city state (“the body is one and has many members”, 12:12) as well as what may be a reference to a developing baptismal liturgy within the early church (“we were all baptised into one body”, 12:13) and a very early creedal statement (“Jesus is Lord”, 12:3).

Throughout these chapters, those who are inclined to diverge from Paul’s commands are portrayed in negative terms: they are “contentious” (11:16), showing “contempt” (11:22), acting “in an unworthy manner” (11:27) and with “dissension” (12:25); their behaviour conveys dishonour (12:22–26) and shame (14:35).

The selfish behaviour of some at the common meal warrants their condemnation (11:32) and justifies the illness and death that has occurred within the community (11:30). The individualistic participation of others in communal worship builds up themselves, but not others (14:4, 17); they are not intelligible in speech (14:9), but are unproductive in their minds (14:14) and childish in their thinking (14:20), leaving themselves open to the risk, “will they not say that you are out of your mind? (14:23).

In the centre of this section stands the famous “hymn to love” (12:31–13:13), now often treated in isolation and over-romanticised. In context, the passage provides a sharp, pointed polemic against the Corinthian community. The qualities they possess are consistently inadequate when measured against love.

The speech of the Corinthians is like “a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal” (13:1), an allusion to the mayhem brought about by speaking in tongues in worship (1:5; 12:10, 28–30; 14:6–8). Whilst they readily express their “prophetic powers” in worship (11:4–5; 12:10, 28–30; 14:1, 4–5, 23–24, 29–32, 37, 39), for Paul, these abilities are nothing without love (13:2).

Likewise, they claim that they are able to understand mysteries (2:7; 4:1; 14:2, 23) and have knowledge (1:5; 8:1–3, 7, 10, 11; 12:8; 14:6) as well as faith (2:5; 12:9; 15:14, 17; 16:13); but Paul insists that all of these are nothing in isolation from love (13:2).

Elsewhere in his letter, Paul directly accuses the Corinthians that they are precisely what love is not. Love does not boast (13:4), but Paul regards the the Corinthians as being boastful (1:29; 3:21; 4:7; 5:6). Love is not arrogant (13:4), but in Paul’s eyes the Corinthians are arrogant or “puffed up” (translating the same Greek word in 4:6, 18–19; 5:2; 8:1).

Love does not rejoice in wrongdoing (13:6), but Paul berates the Corinthians for taking fellow-believers to court to seek redress for wrongs; indeed, “you yourselves wrong and defraud—and believers at that” (6:7–8). Love means that people do not insist on their own way (13:5), but Paul considers that the way that some behave in relation to meat offered to idols in the marketplace advantage; “do not seek your own advantage”, he advises them, “but that of the other” (10:24).

In like manner, when they gather to celebrate the supper of the Lord, “when the time comes to eat, each of you goes ahead with your own supper, and one goes hungry and another becomes drunk” (11:21). Selfishness and acting without regard for the other characterises their common life.

Love “hopes all things” (13:7), but some in the community at Corinth are accused of failing to share in the hope of the resurrection (15:12–19). The assertion that “we know only in part” (13:9–10) is directed squarely against the Corinthian claim to have full knowledge (8:1, 10–12) whilst the image of the child, not yet adult (13:11), reflects Paul’s criticism of the Corinthians as infants, not yet ready for solid food (3:1–2; 14:20).

So the hymn alleged to be in praise of love is, more accurately, a polemical censure of the Corinthians’ shortcomings, in which every word used and every phrase shaped by Paul cuts to the heart of the inadequacies of the Corinthian community. Try preaching that at a wedding!!