The passage we explore today takes us into the world of politics in ancient Judea. It is the story of Herod, Herodias, and John the baptiser (Mark 6:14–29). The Herod in this story is Herod Antipas, the son of Herod the Great, who features in Matthew’s account of the birth of Jesus, as the ruler ordering the killing of “all the children in and around Bethlehem who were two years old or under” (Matt 2:16). He is the same Herod to whom Jesus was sent in the course of his trial before Pilate—at least, according to Luke’s account (Luke 23:6–12).

Just as the birth and death of Jesus are each immersed in the politics of the day, so too the death of John the Baptist is best understood in terms of the politics of the day. The story appears at this point, midway through Mark’s narrative, even though John had been beheaded at the command of Herod Antipas some time earlier (Mark 6:17).

Luke, in fact, locates the arrest of John immediately after reporting his baptising and preaching activity “in the wilderness” (Luke 3:1–20), before mentioning, in a brief aside, that Herod had beheaded John (Luke 9:9).

Mark, once again, provides us with plentiful details about the incident: Herod’s protection of John (Mark 6:20), that he liked to listen to John (6:21), his granting of a wish to his daughter Herodias (6:22), the consultation Herodias then had with her mother (6:24), the grief of Herod when he had to adhere to his promise to fulfil the wishes of Herodias (6:26), and the reverent disposal of John’s body by his disciples (6:29). Matthew reports each of these elements, with far fewer words—although he does add that John’s disciples, after burying his body, “went and told Jesus” (Matt 14:12).

Luke omits all of these details, noting only the arrest and the beheading of John in terse narrative comments. John makes no mention at all of Herod, and in his Gospel the figure of the Baptist serves primarily to point to Jesus as Messiah (John 1:6–8, 15, 19–28, 29–34; 3:25–30; 5:33; 10:41). John the evangelist knows that John was baptising (3:23), in apparent competition with the disciples of Jesus (4:1–2); perhaps these were the disciples of John who left him to follow Jesus (1:35–42)? The evangelist also knows that he was arrested (3:24), but reports nothing of his death.

So Mark offers a rich narrative with many details. It seems that this was a story “doing the rounds” at the time. The story criticised Herod—who was not popular among the Jews. Telling the story gave an indirect way to criticise him, albeit in an indirect way. The “hero” of the story—John, who tragically meets his death—is the polar opposite of Herod. John was austere, ascetic, and obedient to God; Herod was profligate, extravagant, and ran his territory of Galilee according to Roman custom.

One detail that neither Mark, nor the other evangelists, includes, is that the Hebrew name of Herodias, the daughter of Herod Antipas, was Salome—the name by which she is best known in subsequent art and literature. Salome’s “dance of the seven veils” (another detail absent from the Gospel narratives!) is renowned, having inspired paintings by Titian and Moreau, an 1891 play by Oscar Wilde, a 1905 opera by Richard Strauss, and a 1953 film starring Rita Hayworth.

Indeed, in his recent book Christmaker (Eerdmans, 2024), Prof. James McGrath observes that “the best-known elements of the story—the dance of Salome, the promise of Herod, and John’s head on a platter—are the ones about which a historian has the most reason to be sceptical” (p.116).

In fact, even in a number of manuscripts (from the 500s onwards, and especially in the Latin versions), the name of the woman we find named in our Bibles as Herodias (6:22) is missing; in these, she is called “the daughter of Herodias” (and thus the granddaughter of Herod Antipas). But this is a minor point compared to some other factors.

So what do we make of this story? Why has Mark chosen to tell it?

Three Herods: untangling the knots

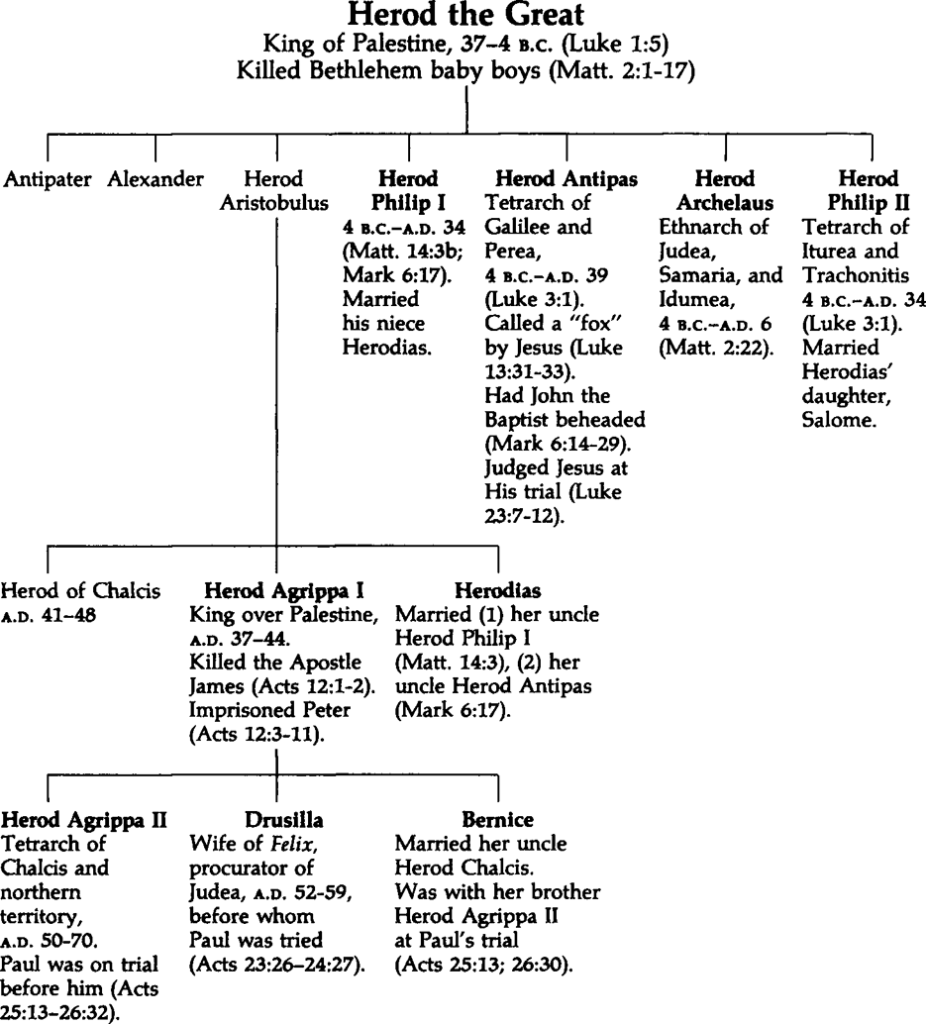

The Herod who appears in this story that Mark and Josephus each tell is one of three Herods mentioned in the New Testament. What follows is an attempt to untangled the knots of history and make clear where each Herod fits.

We begin with the Roman general Pompey leading Roman troops into Jerusalem in 63 BCE. Pompey granted Hyrcanus II the throne, under Roman oversight; Hyrcanus II ruled until 40 BCE. As a Roman protectorate, Judea had the right to have a king. Hyrcanus was a Hasmonean, a member of a priestly family that had worked itself into a position of power in Jerusalem after the revolt in the time of Antiochus Epiphanes (175—167 BCE).

The revolutionary activity of the Maccabees, led by a priest, Mattathias, and his five sons, sought to expel the foreigners from Israel. When Antiochus had a pagan symbol placed into the holy Temple, “Mattathias and his sons tore their clothes, put on sackcloth, and mourned greatly” (1 Macc 2:14). In the face of orders from the king’s officers, Mattathias declared, “I and my sons and my brothers will continue to live by the covenant of our ancestors. Far be it from us to desert the law and the ordinances. We will not obey the king’s words by turning aside from our religion to the right hand or to the left” (1 Macc 2:20–22).

The family of Mattathias and their followers were given the Hebrew name Maccabees, meaning hammer—reflecting the hammer blows they struck, again and again, against their enemies. From 167 BCE they fought an armed insurgency which eventually brought victory over the Seleucids in 164 BCE. For a time, Jews would rule Israel once again.

The family given the name Maccabees had at its centre a number of descendants of Hashmon (referred to by Josephus as Asmoneus at Jewish Antiquities 12.265). Thus the string of rulers drawn from this family for the ensuing century, until 63 BCE, are known as the Hasmoneans. The first three rulers from this family were sons of Mattathias: Judah (164–160), his youngest brother Jonathan (160–142), and then his oldest brother Simon (142–134). Each, in turn, moved the religious and cultural practices away from the initial zealous intention to restore Torah and Temple to Israel.

The Hasmoneans believed they should not only sit on the throne of Judah, but also exercise the responsibilities of the High Priest. Claiming this religious leadership was not in accord with the tradition that the priests came from the descendants of Aaron, the brother of Moses, descending through the tribe of Levi (Num 1:48–54; 1 Chron 6:48; 2 Chron 13:10–12; Ezek 44:15). That the Hasmonean high priests were not priests in this precise lineage was a problem for the more traditional members of Israelite society, and would foster discontent and rivalry amongst various groups with Israelite society.

In the midst of growing discontent and instability, in 40 BCE the Roman Senate declared Herod of Idumea to be “King of the Jews”. One of Herod’s many wives was Marianne, the granddaughter of both Aristobulus II and Hyrcanus II. (Aristobulus’s son, Alexander, had married Alexandria, the daughter of Hyrcanus. They were the parents of Marianne.) So he had married into the Hasmonean family.

It is said that Antigonus, the brother of Alexander and son of Aristobulus, had cut off Hyrcanus’s ears to make him unsuitable for the High Priesthood, so Antigonus ruled for three years in defiance of Rome’s decree. Herod, with the support of Mark Anthony, seized power in 37 BCE and held power until his death in 4 BCE. Hasmonean rule was at an end; Herod was an Idumean, the son of an Idumean man, Antipater, who served in the court of Hyrcanus II, and his wife Cypros, from a Nabatean Arab princess. He has been raised as a Jew, but to many Jews he was not a Jew, but an Idumean (the kingdom that had evolved from the Edomites, to the south of Judah).

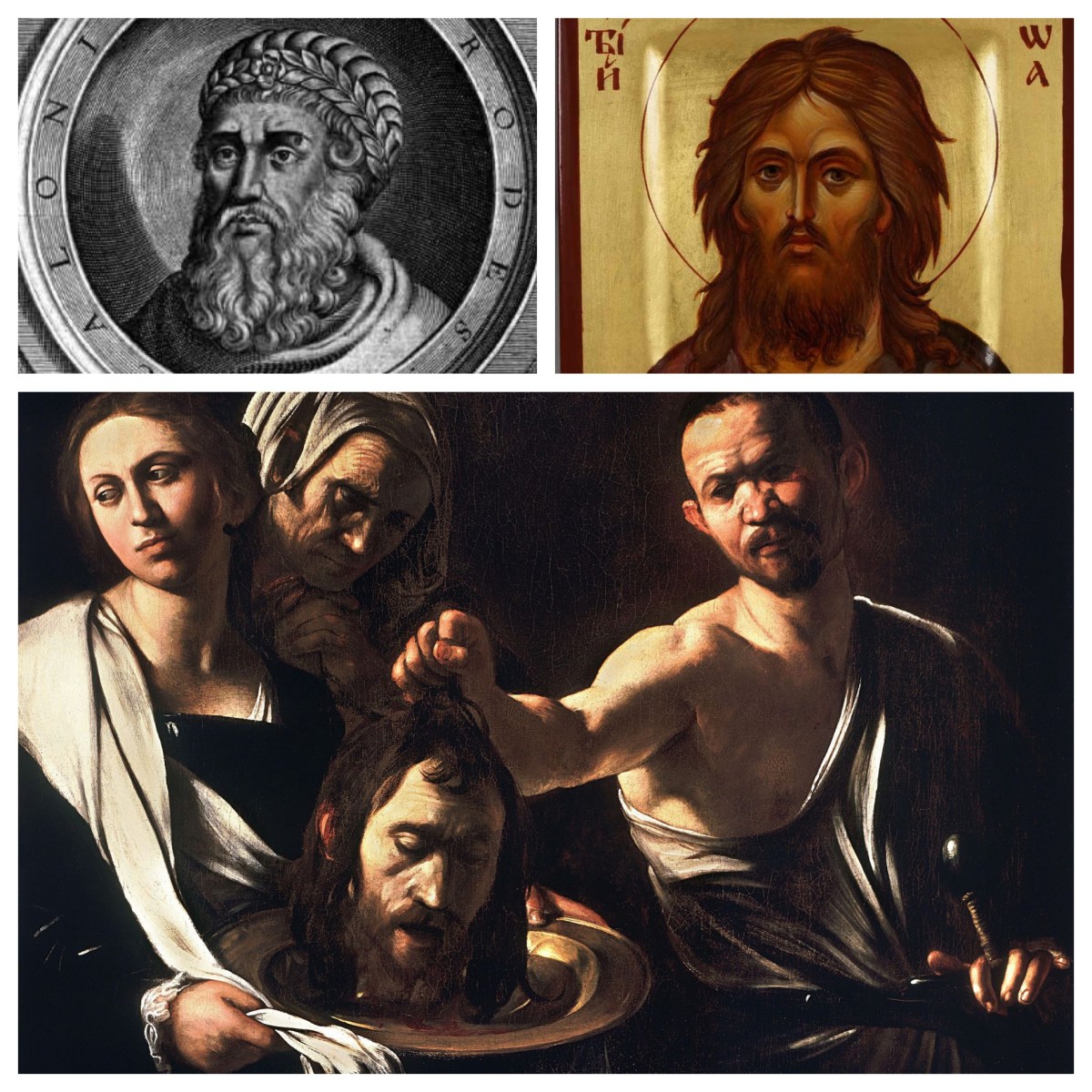

in light of the tradition that he was born in Ashkelon;

one of his younger sons, Herod Antipas (bottom left),

and his grandson through Aristobulus,

Herod Agrippa (bottom right)

Later, after the death of Herod, one third of his kingdom (the region of Galilee) came under the control of Herod Antipas, the son of Herod the Great and one of his wives, Malthace, from Samaria. Herod senior was “Herod the Great”, the king who, according to Matthew, ordered the slaughter of all males born in Israel (Matt 2:16–18).

Herod Antipas, his son, was, according to Mark, the ruler who, against his better judgement, ordered the beheading of John the baptiser (Mark 6:17–29). Herod Agrippa was another member of the family, a grandson of King Herod by another of his wives, Mariamne, who ruled as King of Judea from 41 to 44 CE. He appears as “King Agrippa” in Acts 24—25, when Paul is brought to Caesarea, the seat of government, to be judged by Agrippa, his consort Bernice, and the Roman Governor Festus.

So today’s story from Mark 6 involves the middle Herod, Herod Antipas. His relationship with John the Baptist is what lies at the heart of the account in Mark 6.

Why did Herod put John to death?

We actually have two detailed accounts of the death of John. Mark, as we have seen, portrays Herod as equivocating. He tries to move the primary responsibility of John’s death away from Herod, by interspersing his daughter and her request. Perhaps Mark feels the need to excuse the Roman-supported ruler of the time, to avoid having the Jesus movement portrayed as a terrorist movement?

After all, even though Jesus was clearly crucified under orders from the Roman Governor, Pilate (Mark 15:15), Mark does have Pilate bow to the pressure of the crowd that is calling out “crucify him”, by asking the question, “what evil has he done?” (15:12–14). It is Mark who provides our earliest source for placing the blame on the chief priests”, who had stirred up the crowd to press for Jesus to be crucified (15:10–11). So if there an apologetic purpose in the passion narrative—blame the Jews, excuse the Romans–then is a similar apologetic happening in the story of John’s death?—blame Herodias, excuse Herod.

There is an account written later than Mark, by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, in his history of the Jews, which he wrote under Roman patronage in the latter decades of the first century CE. Here, Josephus pins the blame squarely on Herod.

Herod Antipas had divorced his first wife Phasael, who was the daughter of the king of Nabataea. Herod Antipas then married Herodias, who had previously been married to Herod’s half-brother Herod II. John was publically critical of this (Mark 6:18; Matt 14:4; Luke 3:18).

John’s criticisms of Herod’s divorce and subsequent marriage did not sit well with Herod. John’s popularity meant that he was persuading many others to this negative view of Herod. Indeed, God later vindicates the criticisms made by John, according to Josephus, who says that God punished Herod by his later defeat in battle. Josephus writes:

“Herod had put him to death, though he was a good man and had exhorted the Jews to lead righteous lives, to practise justice towards their fellows and piety towards God, and so doing to join in baptism.

“In [John’s] view this was a necessary preliminary if baptism was to be acceptable to God. They must not employ it to gain pardon for whatever sins they committed, but as a consecration of the body implying that the soul was already thoroughly cleansed by right behaviour.

“When others too joined the crowds about him, because they were aroused to the highest degree by his sermons, Herod became alarmed. Eloquence that had so great an effect on mankind might lead to some form of sedition, for it looked as if they would be guided by John in everything that they did.

“Herod decided therefore that it would be much better to strike first and be rid of him before his work led to an uprising, than to wait for an upheaval, get involved in a difficult situation and see his mistake. Though John, because of Herod’s suspicions, was brought in chains to Machaerus, the stronghold that we have previously mentioned, and there put to death, yet the verdict of the Jews was that the destruction visited upon Herod’s army was a vindication of John, since God saw fit to inflict such a blow on Herod.” (Jewish Antiquities 18.116–19)

Josephus sides with God, in arguing that Herod did the wrong thing by putting John to death—and he paid for it later on. Mark sides a little more with Herod, in seeking to excuse him and shift the blame elsewhere.

So we might well ponder: How do we respond to the idea that as they tell the story of John and Herod, both the evangelist Mark, and Flavius Josephus have apologetic purposes? Josephus puts the blame on Herod. Mark shapes the story to excuse certain people and shift the blame to others. Does this cause us to question the historical value of these texts? Are we more inclined to believe Mark rather than Josephus? or the other way around? Why might that be?

John and the prophetic tradition

The fact that Herod finds John to be of interest is rather unusual. As a ruler under Roman control, he might be expected to want to repress Jewish voices, to ensure that order is kept in society. And yet, Herod has a Jewish heritage, and would know of the importance of the voice of the prophets within that heritage.

Nathan called out David for his adultery (2 Sam 12). Elijah spoke boldly against King Ahab (1 Ki 17–19, 21) and King Ahaziah in Samaria (2 Ki 1). Elisha spoke out to King Jehoram (2 Ki 3). Amos spoke out against King Jeroboam (Amos 7). Isaiah declared the word of the Lord to Hezekiah (2 Ki 20).

Haggai likewise guided Zerubbabel, the governor of Judah, after the exile (Hag 1) and at the same time Zechariah was making declarations to King Darius of Persia (Zech 7). The role of the prophet was to be an essential, irritant in the ears of rulers, to be the niggling (and perhaps even booming) voice in the ears of rulers.

John stands, it would seem, in that tradition. Not only was he an irritant to “people from the whole Judean countryside and all the people of Jerusalem” (Mark 1:5), calling them to repentance and baptizing them as they confessed their sins. He was also, according to this story, an irritant to the ruler of the time—Herod Antipas. Herod, Mark says, regarded John as “a righteous and holy man” (6:20)—high praise indeed. Herod, Mark says, “protected” John and “liked to listen to him” (6:20). And yet, he is persuaded to arrest and then behead John, not of his own initiative, but by keeping the promise he had made to Herodias (6:26–28).

We have noted briefly that the stories of the death of John and the death of Jesus have certain similarities. John functioned as a prophet, apparently speaking to those in power. Jesus also conducted himself in a prophetic manner, speaking about the kingdom which God was going to bring in—although he talked about this, not directly to those in power, but to the people of Galilee and, ultimately, of Jerusalem.

John’s popularity was his undoing; it seemed that many liked to listen to John and accepted his criticisms of Herod and Herodias. Jesus’s popularity was also his undoing. Large crowds had followed Jesus since early in Galilee (2:13; 3:20, 32; 4:1; 5:21; 24, 30–31; 6:34; 7:14; 8:1–2, 34; 9:14–15, 25; 10:1, 46; 11:18; 12:37).

The Jewish leadership in Jerusalem were offended at the teachings they heard from Jesus in the temple; “they wanted to arrest him, but they feared the crowd” (Mark 12:12). in similar fashion, Mark notes that those priests and scribes “were afraid of the crowd, for all regarded John [the Baptist] as truly a prophet” (11:32).

In many churches today, “good discipleship” or “being a good Christian” would seem to be equated with “being a good citizen”. John provides a model that steps out of the bounds of “good citizenship”. Is this a model for us to consider? For instance, in the Code of Ethics and Ministry Practice in my own church (the Uniting Church in Australia), section 6.2 states that “It is unethical for Ministers deliberately to break the law or encourage another to do so. The only exception would be in instances of political resistance or civil disobedience.”

Ministers have been arrested for protesting against laws that they believe, as a matter of conscience, to be unethical, or against their principles. They are standing in the tradition of John and the prophets before him—although nobody who has done this has, to my knowledge, been beheaded like John was!!

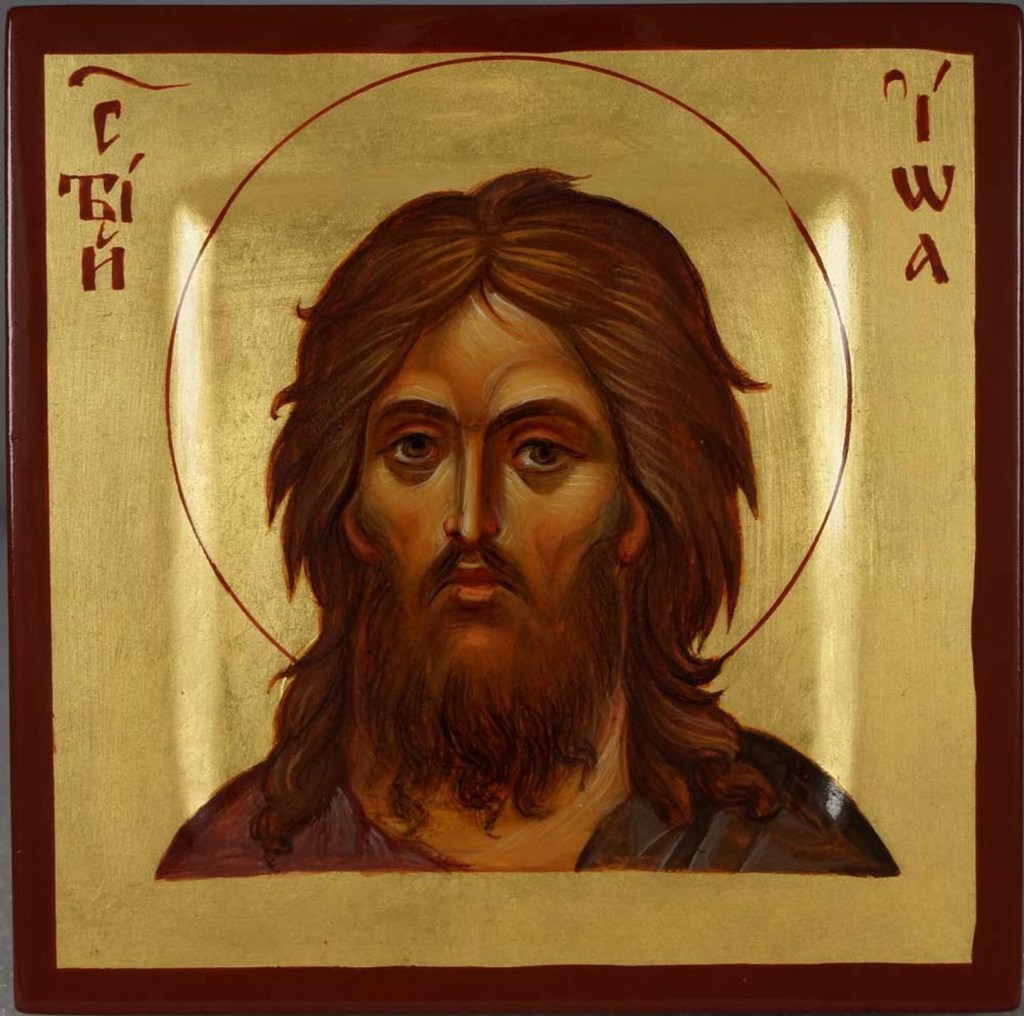

Salome with the Head of John the Baptist

(c. 1607–1610; National Gallery, London)