For the passage from Hebrew Scripture this coming Sunday, the lectionary offers us selected verses from 2 Sam 6:1–19. Last week, we heard the brief account of how David, the king of Judah, took the city of Jerusalem from its inhabitants, the Jebusites, and was anointed as king of “all Israel” (5:1–10). Next week, we will hear of the promise that God makes to David, that “I will make for you a great name … your throne shall be established forever” (7:1–14).

In between these two pivotal events, establishing beyond doubt that David was both the conqueror supreme of the earlier inhabitants and the progenitor of a dynasty—“the house of David”—that would hold power for centuries to come, we have a curious, yet significant, account relating to The Ark of the Covenant (6:1–19). David uses the Ark to reinforce and undergird his authority; his intention in bringing into the city, Jerusalem, was to confirm absolutely that he was God’s anointed, in Jerusalem, ruling over all Israel.

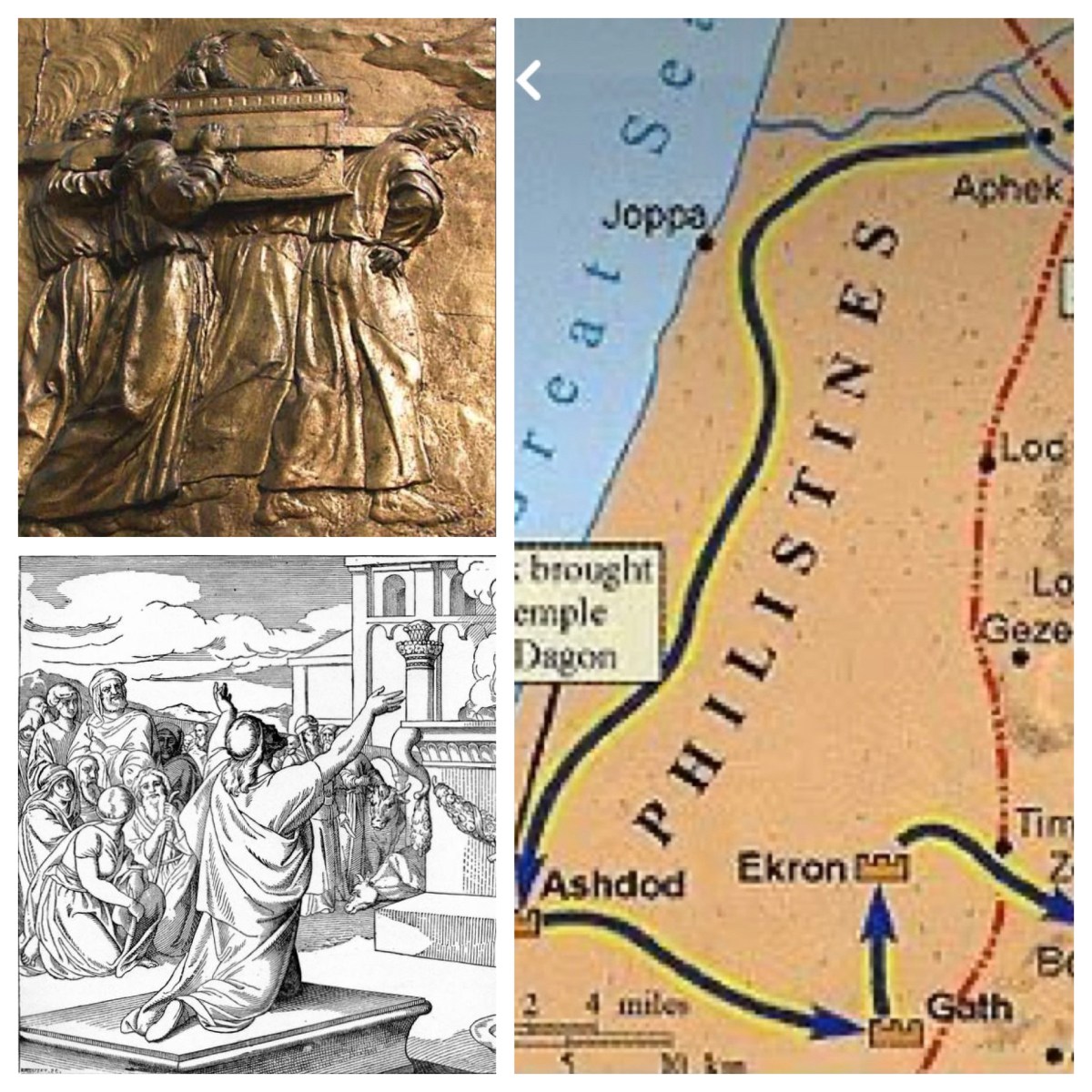

The Ark of the Covenant had long been a focal point for people in Israel. It had travelled with them from the wilderness days (Num 10:33–36), being carried along the way by the Levites (Deut 10:8). In the book of Deuteronomy, it is important because it contained “the book of the law” which Moses had written, and which was to be read to the people of Israel every seven years (Deut 31:9–13; se also Exod 40:20).

Another perspective is offered in the priestly prescriptions relating to the complex system of sacrifices and offerings that was overseen by the priests, that are reported in excruciating detail in Exodus 25—30 and then again in Leviticus 1—7. Here, the significance of the Ark is primarily that it contained the Mercy Seat (Exod 25:17–22). It was the smearing of blood on the Mercy Seat, performed once a year by the High Priest on the Day of Atonement, that secured the forgiveness of all the sins of the people from the past year (Lev 16:1–34; see esp. vv.14–15).

The narrative of Numbers draws these two strands together, when it reports that “when Moses went into the tent of meeting to speak with the Lord, he would hear the voice speaking to him from above the mercy seat that was on the ark of the covenant from between the two cherubim; thus it spoke to him” (Num 7:89). So the significance of the Mercy Seat in the Ark of the Covenant is high.

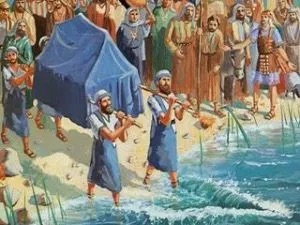

Regardless of the significance invested in the Ark, its presence with the people during the 40 years in the wilderness was important. It appears at the end of that period of time, when Joshua prepares to lead the people into the land of Canaan. On the command of Joshua, “while all Israel were crossing over on dry ground, the priests who bore the ark of the covenant of the Lord stood on dry ground in the middle of the Jordan, until the entire nation finished crossing over the Jordan” (Josh 3:17). The miraculous power of the Ark is thus demonstrated.

was photography at the time???

It is referred to only once in the whole of Judges, in the closing scenes, after the abomination perpetrated by the Benjaminites in Gibeah (Judg 19). The Israelites had “inquired of the Lord (for the ark of the covenant of God was there in those days)”, and received the voice of God from the ark, “go up, for tomorrow I will give them into your hand” (Judg 20:27).

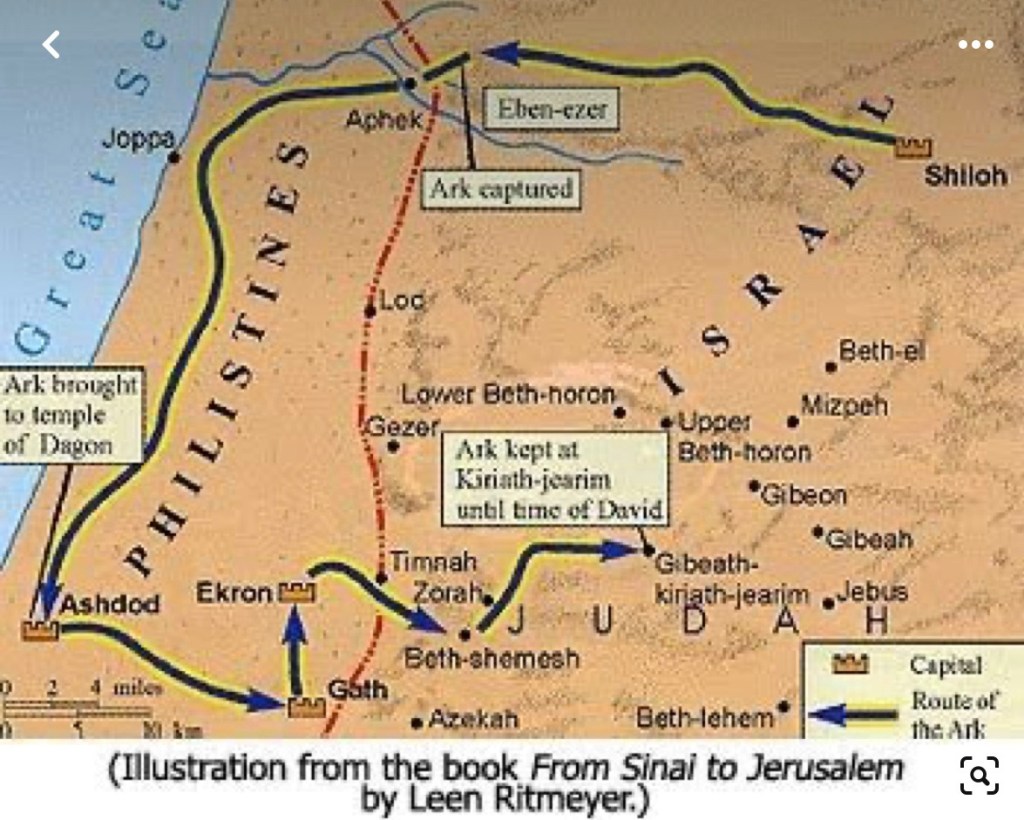

Soon after, in the very first battle with the Philistines in 1 Samuel, the Ark was captured. It had been in “the temple of the Lord” at Shiloh when Eli was priest (1 Sam 1:20, 24-28; 3:2–3), but after losing their encounter with the Philistines at Aphek, the Israelites decided to bring the Ark from Shiloh to the battlefield to reverse the result (4:1–4). The presence of the Ark, at first discomforting to the Philistines, was not able to turn the tide; “Israel was defeated, and they fled, … there was a very great slaughter, for there fell of Israel thirty thousand foot soldiers; the ark of God was captured” (4:10–11).

The Ark was sent first to Ashdod (5:1), then to Enron (5:10), before it was returned to Israel seven months later (6:1–16). They had placed inside the Ark “five gold tumours and five gold mice, according to the number of the lords of the Philistines” (6:4–5), “one for Ashdod, one for Gaza, one for Ashkelon, one for Gath, one for Ekron” (6:17). These images served as a guilt offering to the Lord God, in the hope that they would be “healed and ransomed” (6:3).

But the people of Beth-shemesh shied away from having this potent artefact in their village; after all, it has killed seventy descendants of Jeconiah who “did not rejoice with the people of Beth-shemesh when they greeted the ark of the Lord” (6:17). So it was sent on to Kiriath-jearim, where it remained without incident for 20 years (7:1–2).

The Ark then fades from the story during those years, as the narrative turns to the question of kingship (1 Sam 8—10) and Saul is eventually anointed as King (10:1). It remains absent from the accounts of Saul’s battles (1 Sam 11—14) until, out of the blue, Saul calls for the Ark to be brought to Gibeah, in the hill country of Ephraim, where he had made his base (1 Sam 14:16–18), and the particular battle being waged against the Philistines was won (14:23). Presumably it continues its travels with Saul; the next time it is mentioned is in the story we read this week in 2 Sam 6.

in an illuminated manuscript held by the J. Paul Getty Museum.

In this week’s story, David effects a change in the role played by the Ark. It is brought into Jerusalem and stays grounded there; in due course, a permanent temple will be built on the site under Solomon. When David is forced to flee the city (2 Sam 15:13–18), he takes the Ark with him to the edge of the wilderness (15:23–24), but then orders it to be sent back into the city (15:25–29). The Ark will remain as a symbol of his rule over the city and, indeed, the whole nation.

Writing in With Love to the World, Michael Brown reflects on the militaristic colonizing of King David, as he consolidates and reinforces his dominance. He observes that “David, the just-minted king of an expanded territory was starting something big and new. His royal city, permanent army, and large harem pointed to a very different reign. Yet those who prized the traditions might have queried whether this reign had legitimacy.”

This is where the Ark comes into play. Brown continues, observing that it was now “perfect timing for the ark, languishing in the back blocks but traditionally identified closely with God’s presence, to be brought by David to the new royal city as a symbol of God’s blessing.”

The Ark once again does not feature in the story told in the ensuing chapters, until after David has died (1 Ki 2:10). Once he is king, Solomon “came to Jerusalem where he stood before the ark of the covenant of the Lord; he offered up burnt offerings and offerings of well-being, and provided a feast for all his servants” (1 Ki 3:15). The Ark was due to be superseded by the Temple, in whose inner courtyard the Ark would be placed (1 Ki 6:19).

And so, at the dedication of the Temple, “the priests brought the ark of the covenant of the Lord to its place, in the inner sanctuary of the house, in the most holy place, underneath the wings of the cherubim” (1 Ki 8:6, 21). The narrator declares that “there was nothing in the ark except the two tablets of stone that Moses had placed there at Horeb, where the Lord made a covenant with the Israelites, when they came out of the land of Egypt” (1 Ki 8:9).

Cathedral of Sainte-Marie, Auch, France.

We hear nothing more of the Ark until centuries later when Jeremiah, in exile, reports the words of the Lord: “when you have multiplied and increased in the land, in those days, they shall no longer say, “The ark of the covenant of the Lord.” It shall not come to mind, or be remembered, or missed; nor shall another one be made.” (Jer 3:16). According to an even later report, Jeremiah himself had taken “the tent and the ark and the altar of incense” and his them in a cave on “the mountain where Moses had gone up and had seen the inheritance of God” (2 Macc 2:1–5, referring to Mount Sinai of Exod 19:16–25; 24:15–18).

Cue the movie featuring Indiana Jones and the raiders of the lost ark … … …

A critical issue for us, from the story of the Ark and how it was used in ancient Israel, is the interplay between political and religious leadership that is portrayed in the Hebrew Bible narratives.What might tgat mean for people of faith today, as we reflect on and live out our faith in the public life of society?

Throughout all ancient societies, religion was very closely linked to the political situation of the particular society. In the years leading up to the story that we hear this coming Sunday, the people of Israel had been engaged in one war after another. Even when the Israelites were settled in the land, they did not have control of the whole of the land of Israel. Only after he has won victory in a number of battles, could David claim to be king of Israel. The story we hear this Sunday was when the whole land had, at last, been placed under his control.

To celebrate, he declares that Jerusalem is to be the capital city, and to commemorate this event, the Ark is brought into the new capital city. From this point onwards, not only is Jerusalem the political capital of Israel, but it is also the place where God dwells, where God is to be found.

David knows that the ruling monarch must be seen to be favoured by God. What better way than to make his chosen capital the centre of the religion of Israel? Any disgruntled Jews from the northern kingdom cannot attack David’s city without seeming to attack God, so David has astutely consolidated his grip on the monarchical power.

In one way, it makes sense to link religious celebration with political victory. This is a natural connection that people have often made throughout history – thanking the god who they worship when a significant military victory is won.

But it is also a dangerous practice. It can lead to political leaders making claims about God being on their side and not on the other side. It can lead to arrogant actions. It can lead to a distortion of religion, when it is pressed into the service of the state. The kings of ancient Israel are not immune to these charges; from Samuel onwards, prophet after prophet had made it very clear that kings frequently put self and power before their obedience to God.

In today’s world there are many instances of corrupt governments and abuse of power, where human rights are ignored and God’s name is abused. Russia, China, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, various Middle Eastern countries, Myanmar and some other Asian nations, and quite a number of sub-Saharan African countries come to mind. And even democracies, heading by the United States of America, display indications of the abuse of power and the presence of corruption. The problem is endemic.

As people of faith, we need to be on our guard against the temptation to use our faith to claim superiority or act unethically. Rather, our faith should guide us to act in ways that influence for good the politics of the society in which we live. Only then can we expect the church to inspire and transform the society around us. Only then can we truly be called people of God.

See also

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.

You can subscribe on your phone or iPad via an App, for a subscription of $28 per year. Search for With Love to the World on the App Store, or UCA—With Love to the World on Google Play. For the hard copy resource, for just $28 for a year’s subscription, email Trevor at wlwuca@bigpond.com or phone +61 (2) 9747-1369.