This coming Sunday, we read the story of David’s adultery with Bathsheba (2 Sam 11:1–15). This story is known and remembered through the ages—although it is often misinterpreted, in explanations that “blame the woman” for what, in the text, is clearly a series of actions undertaken explicitly by the man who has power, the man who decides to “take” the woman. In this regard, this ancient story resonates strongly with the experience of millions, if not billions, of women in the modern world. The #MeToo movement attests to the ongoing occurrence of sexual exploitation and abuse of women by men with power.

So the man, David, is depicted as exercising a shameful demonstration of sheer power, expressed through sexual violence. He was the King of Israel, and so had become accustomed ordering people around and getting what he wanted.

And it was, after all, “the spring of the year, the time when kings go out to battle” (2 Sam 11:1). He should have been with his troops as they were fighting the Ammonites, but instead he was walking on the rooftop, looking down into the bathing room of a nearby house where Bathsheba was bathing.

Let’s note that it was David who was up on the roof; Bathsheba was not bathing on the roof; he was looking down on her. The text is explicit: “David rose from his couch and was walking about on the roof of the king’s house, [when] he saw from the roof a woman bathing” (11:2). We’ll come back to him in a subsequent post.

In what follows, I am grateful to my wife, Elizabeth Raine, for what she has shared with me as we have explored this story. Elizabeth has spent much time with the texts relating to Bathsheba, and I have benefitted from her knowledge—and, of course, from the female perspective on this story which males need to hear and understand and appreciate.

The woman, Bathsheba, by contrast to the man, is apparently compliant in their coming together; well, what choice did she have, as David was the king, ruler supreme, with courtiers and soldiers ready to do his bidding? She had no chance, it would seem, of avoiding the trap set by David. And it is noteworthy that we hear nothing, in this narrative, of her thoughts about the whole incident. She is completely without voice in the story.

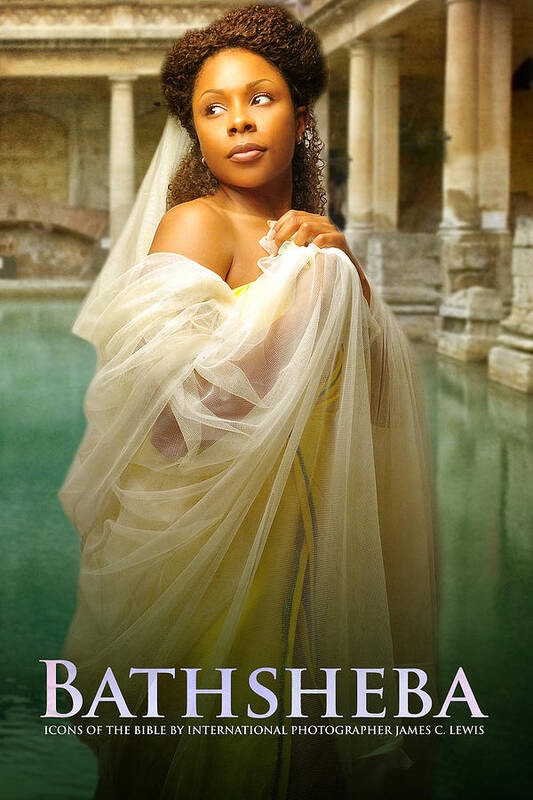

When we first meet Bathsheba in this passage, she is described as “very beautiful” (2 Sam 11:2). Let’s remember that David himself was first revealed to the readers and hearers of the ancient narrative saga as “ruddy, he had beautiful eyes and was handsome” (1 Sam 16:12). The same had been said of handsome Joseph (Gen 39:6), “a handsome young man” named Saul (1 Sam 9:2), and the same would later be said of Adonijah, a son of David (1 Ki 1:6), and much later of Daniel, with his companions in the Chaldean court (Dan 1:4). Commenting favourably on the physical appearance of a character was part of the craft of the ancient storyteller.

Bathsheba stands in a line of even more women who are introduced into the story as “beautiful”: Sarai (Gen 12:11), Leah and her sister Rachel (Gen 29:17), Abigail (1 Sam 25:3), Tamar, the daughter of David (2 Sam 13:1; 14:27), Abishag the Shunnamite (1 Ki 1:3–4), as well as Hadasseh, known as Esther (Est 2:7), the daughters of Job Job 42:15), and the “black and beautiful” lover in the Song of Songs (Song 1:5, 15–16; 4:1, 7), praised as being “as beautiful as Tirzah” (Song 6:4).

Alongside this, Bathsheba is identified in the typical terms of the day, through her relationships with key men: “Bathsheba, daughter of Eliam, the wife of Uriah the Hittite” (11:3). However, although Bathsheba has married a foreigner, a Hittite, she did have an Israelite lineage. Her father, Eliam, is identified as the son of “Ahithophel the Gilonite” (2 Sam 23:33)—that is, he was from Giloh, a town in Judah (2 Sam 15:12) which is listed amongst the towns in “the hill country” that were taken under Joshua’s command and allocated to Judah (Josh 15:51). So she should not be regarded as foreign; she is of David’s own people.

Although we know that the lineage of Uriah was Hittite, from the area to the north of Israel, he nevertheless served in the army of the Israelites, as one of “the servants of David” (2 Sam 11:17). Indeed, we subsequently learn that both Eliam and Uriah were among the chiefs, many of them from foreign tribes, who are numbered amongst “The Thirty” who had joined David’s troops in battle (2 Sam 23:24–38). They were renowned as “mighty warriors” who served David’s cause in these battles (2 Sam 23:8). So Bathsheba’s family had been important for David in gaining and retaining his powerful position.

So the man, David, is depicted as exercising a shameful demonstration of sheer power, expressed through sexual violence. He was the King of Israel, and so had become accustomed ordering people around and getting what he wanted. And it was, after all, “the spring of the year, the time when kings go out to battle” (2 Sam 11:1). He should have been with his troops as they were fighting the Ammonites, but instead he was walking on the rooftop, looking down into the bathing room of a nearby house where Bathsheba was bathing. Let’s note that he was up on the roof; she was not bathing on the roof; he was looking down on her. The text is explicit: “David rose from his couch and was walking about on the roof of the king’s house, [when] he saw from the roof a woman bathing” (11:2). We’ll come back to him in a subsequent post.

As well as this story of Bathsheba’s first encounter with David, she features at two key moments later in the narrative. In 2 Sam 12, we learn the sad news that “the Lord struck the child that Uriah’s wife bore to David, and it became very ill … [then] on the seventh day the child died” (12:15, 18). David, having been physically attracted to Bathsheba and having had intercourse with her, was deeply affected: “he pleaded with God for the child … fasted, and went in and lay all night on the ground” (12:16).

Curiously, once David had learnt that the child had died, he immediately resumed regular life, telling his servants, “while the child was still alive, I fasted and wept … but now he is dead; why should I fast? Can I bring him back again?” (12:21, 23). Strikingly, by contrast, we hear nothing of what Bathsheba felt or thought on this sad occasion. Was she also deeply affected? We might presume so, but the narrator does not choose to convey that.

Did Bathsheba resume normal life as soon as the child died? We might recoil in horror at this thought, and imagine her as carrying out the prescribed period of mourning; but again, the narrator says nothing at all about her reaction. She mourns in silence, unheard, unseen. The woman who was so badly mistreated by the king in her first encounter with him, who learnt that she needed to be subservient to him, has no agency in this later scene. She has been muted.

To his credit, however, the narrator does reveal that David then took care of Bathsheba—although the narrative is sparse at this point, reporting simply that “David consoled his wife Bathsheba, and went to her, and lay with her; and she bore a son, and he named him Solomon” (12:24). Was this to console her, or to satisfy his need for the woman he had chosen to bear him a son and heir? Was his grief for the dying child all about his lineage, rather than for the people involved?

At any rate, amidst the many offspring that David eventually produced (18 sons and one daughter, that we know of), from various wives and concubines, this child, Solomon, was already marked from the start as special; “the Lord loved him, and sent a message by the prophet Nathan; so he named him Jedidiah, because of the Lord” (2:25). Jedidiah means, simply, “beloved of the Lord”.

Bathsheba reappears in the narrative in 1 Kings 1—2, where she speaks as his wife to the king, intervening in matters of the state. First, she attends to the aged, dying king, intervening into the matter of succession. She is introduced here in relation to another male, to whom she was related; this time, she is identified as “Bathsheba, Solomon’s mother” (1 Ki 1:11). Already, as the reign of King David wanes, the star of the future King Solomon was rising.

Her involvement is because she has learnt from Nathan that Adonijah was positioned to succeed David. So Nathan uses Bathsheba to intercede for her son, reminding David of his desire for Solomon to succeed him (1:11–21). David confers with Nathan (1:22–27), and again with Bathsheba (1:28–31), before he orders the action to be taken: “have my son Solomon ride on my own mule, and bring him down to Gihon; there let the priest Zadok and the prophet Nathan anoint him king over Israel” (1:33–34). And so the deed was done. The voice of Bathsheba, at last expressed, was heard. And yet: she only speaks on the urging of Nathan. Her voice is appears conditional, tentative.

Bathsheba is involved in matters of state a second time, after the death of David (2:10), when “Solomon sat on the throne of his father David; and his kingdom was firmly established” (2:12). Here, Adonijah son of Haggith approaches her with a request that she advocate with her son on his behalf (2 Sam 2:13–18). Bathsheba submissively acquiesces to his request, and petitions her son, now the king. Adonijah, it must be noted, was smitten with Abishag the Shunammite, previously described as “very beautiful”, who had served David in his last months (1:1–4).

The intervention of Bathsheba backfires, however; on hearing of Adonijah’s request, King Solomon explodes: “Adonijah has devised this scheme at the risk of his life!” (2:23), and issues the order, “today Adonijah shall be put to death” (2:24). And so, according to the narrator, “King Solomon sent Benaiah son of Jehoiada; he struck him down, and he died” (2:25). Bathsheba has sought exercise her relational influence in these two scenes, seeking to persuade the King on particular courses of action. The first was successful, but not the second. Her attempts to gain a voice in the story of Israel and its kings—one her husband, another her son—seem to be a failure.

After this, there is no further mention of Bathsheba; her son Solomon proceeds to remove other possible contenders for the throne, so that “the kingdom was established in the hand of Solomon” (2:46) and he rules with power and wisdom for decades to come. We remember him primarily for his wisdom. We remember Bathsheba primarily for what David did with her and to her.

The role of Bathsheba in the encounter with David has regularly been misrepresented. In popular (mis)understanding, she is thought to have seduced David. This is not, however, the case. Nothing in the text of 2 Samuel indicates this in any way.

I spent a *happy* eight minutes googling conservative websites to see what they said about Bathsheba’s sin. On setapartpeople.com, we read, “David’s sin was very great, and Bath-sheba’s very small. David’s sin was deliberate and presumptuous; Bath-sheba’s only a sin of carelessness. David committed deliberate adultery and murder; Bath-sheba only carelessly and undesignedly exposed herself before David’s eyes. We have no doubt that David’s sin was great, and Bath-sheba’s small. Yet it remains a fact that Bath-sheba’s little sin was the cause of David’s great sin.” Yoiks.

On gloriouschurch.com, “Anonymous” writes, “Yet the fact remains that it was Bathsheba’s small sin that instigated David’s great sin. It was her minor act of indiscretion, her thoughtless little exposure of her body, that was the spark that kindled a great devouring flame. ‘Behold how great a matter a little fire kindleth!’ On the one side, only a little carelessness, only a little thoughtless unintentional exposure of herself before the eyes of David.”

This website continues, “But on the other side, [she instigates] adultery and guilt of conscience; murder and the loss of a husband; the death in battle of other innocent men; great occasion for the enemies of the Lord to blaspheme; the shame of an illegitimate pregnancy and the death of the child; the uprising and death of Absalom; the defiling of David’s wives in the sight of all Israel; the sword never departing from David’s house (2 Samuel 12:11-18).” Yes, I would remain anonymous, too, after that little diatribe seeking to place the weight of blame for all of David’s sins on Bathsheba!

And various websites, too many to cite and too terrible to actually quote (CBE International, Fossil Creek Church of Christ, My Only Comfort, Elmwood Baptist, the Gospel Broadcasting Network, Moving Towards Modesty … and more), provide careful and specific advice for women and girls on “dressing modestly” (drawing first of all, of course, from 1 Pet 3:1–4) in which the sin of Bathsheba being naked in full sight of the King is cited. (But just try bathing while you are still dressed and taking care of your modesty and still getting properly cleaned !!)

So did Bathsheba seduce David by being naked and stimulating his lust? In fact, the narrative of 2 Sam 11 says no such thing, nor does it provide any warrant at all for suggesting this. Bathsheba is presented as entirely innocent—indeed, as completely passive—in what takes place. Bathsheba is simply taking a bath (v.2).

Yes, Bathsheba was “very beautiful” (v.3), but it was up to David to manage himself appropriately when he happened to see Bathsheba bathing. The common misinterpretation of the incident follows the standard misogynistic practice of blaming the woman for seducing the man, and excusing the man because he was caught by the wiles of the wicked woman. That is not what the text says!

Writing in With Love to the World, Amel Manyon notes that “David used his positional power to force Bathsheba into immorality”, and then observes, “As a leader, we should not use our power to take what does not belong to us. At the time, Bathsheba would have had no choice but to obey her leader, the King—but that is not an excuse for the leader to justify his actions.”

Reflecting on this story in the light of the teachings of Jesus (Mark 9:42–48), James McGrath says, “I’ll take the opportunity to express appreciation for Jesus’ teaching that tells men to pluck out eyes and cut off organs if they are sure they cannot keep from sinning. He doesn’t say to remove someone or something else because it is not the thing that is found tempting that is to blame.” See

The rabbis have much to say about Bathsheba. In the Jewish Women’s Archive, Prof. Tamar Kadari indicates that the Rabbis were well aware of Bathsheba’s innocence and David’s sinfulness. She writes that Bathsheba “had been appointed for David during the six days of Creation, but ‘he enjoyed her as an unripe fruit’, that is, he married her before the proper time, when the fruit [the fig] was still unripe. He rather should have waited until she was ready for him, after the death of Uriah (BT Sanhedrin 107a). This exposition is based on a wordplay, since, in the Rabbinic period, bat sheva was the name of an especially fine type of fig (see Mishnah Ma’aserot 2:8).”

See https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/bathsheba-midrash-and-aggadah

In the Jewish Virtual Library, it is noted that Bathsheba “was not guilty of adultery since it was the custom that soldiers going to war gave their wives bills of divorce which were to become valid should they fail to return and Uriah did fall in battle (Ket. 9b)”. The article also notes that rabbis later held Bathsheba in high regard: “She was a prophet in that she foresaw that her son would be the wisest of men.”

Then the article claims that Bathsheba “is numbered among the 22 women of valor (Mid. Hag. to Gen. 23:1)”—although I can’t find any such list of 22 “women of valour”. There are seven matriarchs—Sarah, Hagar, Rebekah, Leah, Rachel, and Bilhah and Zilpah—and (with one overlap, Sarah), seven prophets—Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah, and Esther—but no list of 22 women. Nevertheless, it is clear that Bathsheba was valued and honoured in rabbinic writings.

And so should we, too; from a most unpropitious start, she ended up an apparently significant character in David’s life, if the stories in 1 Kings 1—2 are to be accepted. And then, of course, in Christian scripture and tradition, this woman is (anonymously) given a place in the lineage of Jesus that Matthew reports in his “account of the origins of Jesus”, when he notes that “David was the father of Solomon by the wife of Uriah” (Matt 1:6b). She is a part of the reason that the (fictive) descent of Jesus from David is claimed; she is one of just four women identified in this genealogy as ancestors of the Messiah himself.

So here’s to Bathsheba! Long may we remember, honour, and value her.

My thanks to Elizabeth Raine for her insights into the character of Bathsheba and the narratives about her.

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.

You can subscribe on your phone or iPad via an App, for a subscription of $28 per year. Search for With Love to the World on the App Store, or UCA—With Love to the World on Google Play. For the hard copy resource, for just $28 for a year’s subscription, email Trevor at wlwuca@bigpond.com or phone +61 (2) 9747-1369.