Over the past three months we have followed the stories about the first three kings of Israel—Saul, David, and Solomon—to the point where we heard Solomon praying for wisdom (1 Ki 3, two Sundays back) and then Solomon praying to dedicate the Temple (1 Ki 8, last Sunday). We also,saw how these two selections present Solomon in a very positive light, whilst other parts of the story reveal a scheming, power-hungry despot. The “nasty” Solomon has disappeared; we have heard only about them “nice” Solomon.

Now the lectionary takes us forward into a series of texts known collectively as “the Wisdom Literature”. Over the next three months, we will hear from a number of the books collected under this rubric in the Protestant Canon of the Old Testament (Song of Songs, Proverbs, Esther, Job, and Ruth). (If you use the lectionary readings for All Saints Day on 1 Nov, you will also encounter the Wisdom of Solomon, a book found in the Deuterocanonical works in the Roman Catholic Canon.)

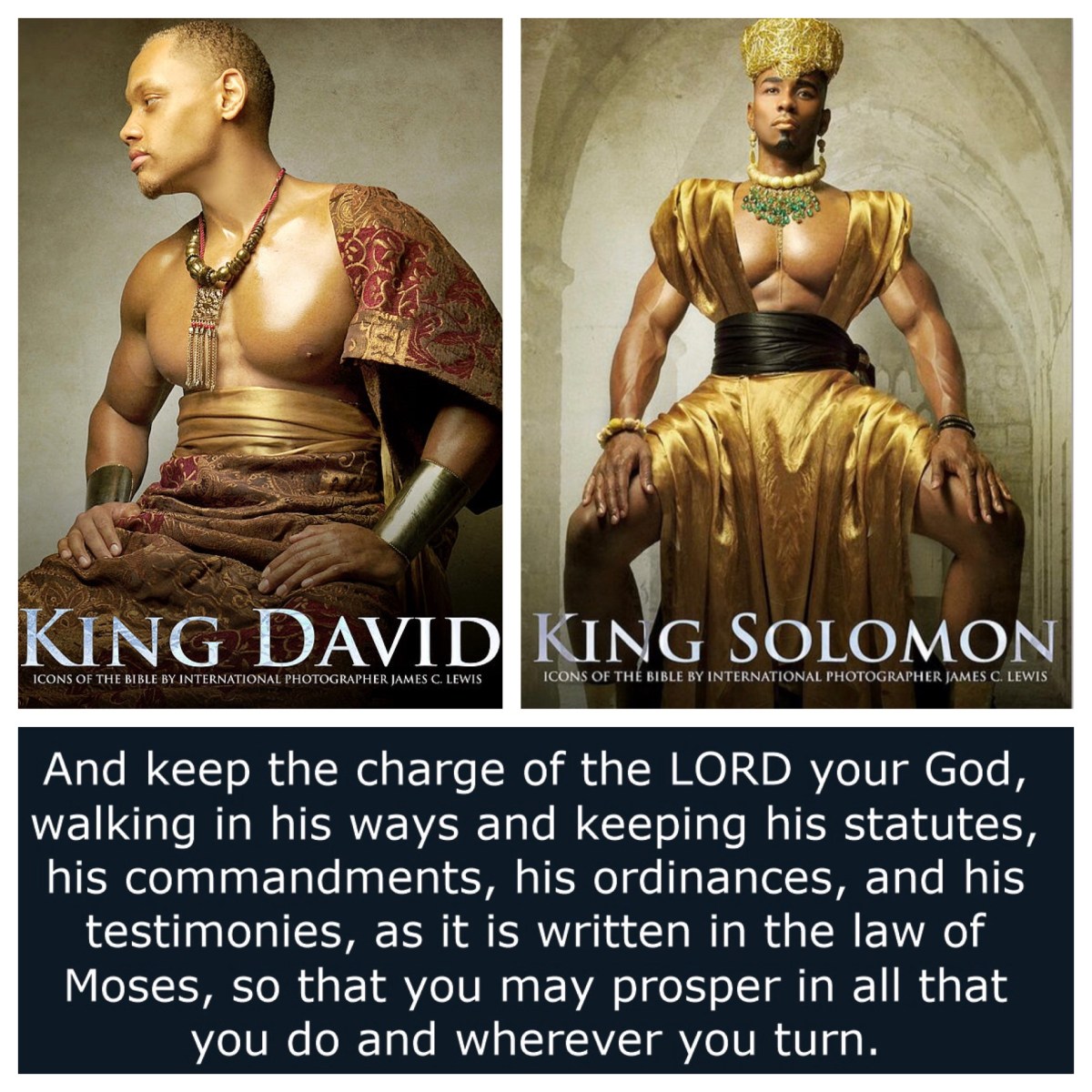

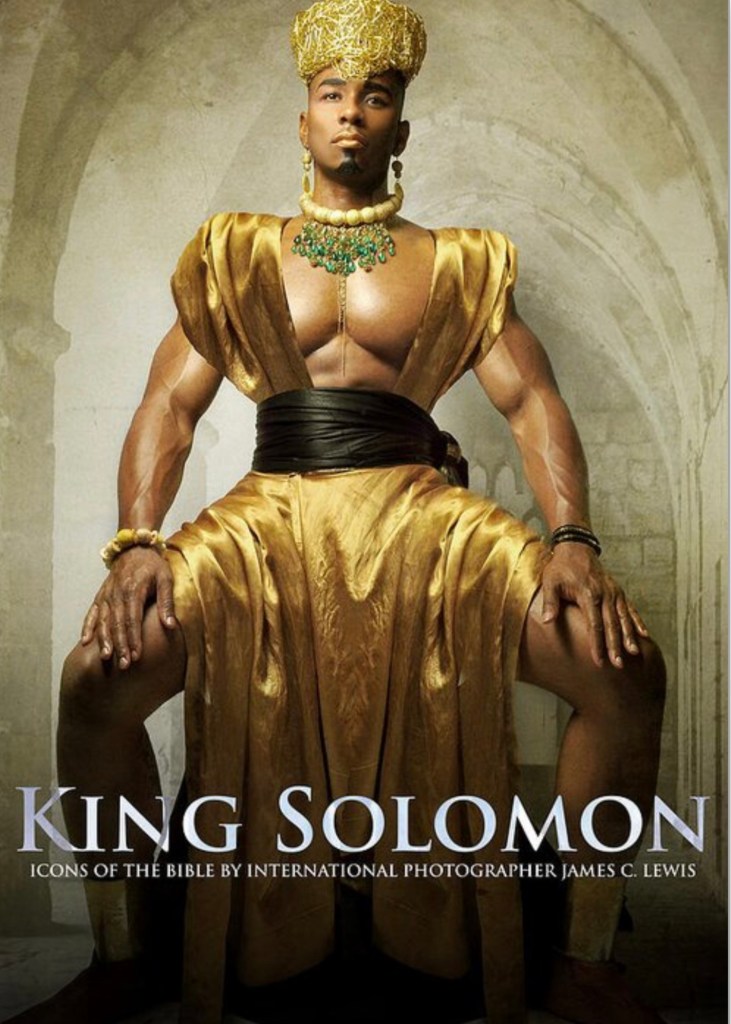

The ongoing tradition has been very kind to Solomon. He is remembered much more for his wisdom than his warmongering. It is his gentle reflections on life that persist in popular imagination, not his aggressive actions towards family members that we saw a couple of weeks back. In 1 Kings 4:32, it is stated that Solomon “composed three thousand proverbs, and his songs numbered a thousand and five”. There are two psalms, Ps 72 and Ps 127, which are attributed to Solomon, while three whole books—Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Songs—are claimed to have been written by Solomon. This is where his legendary wisdom can be accessed!

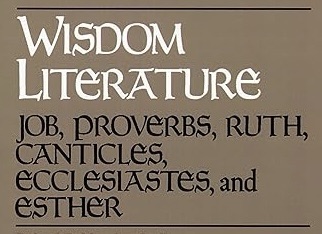

Proverbs begins “The proverbs of Solomon son of David, king of Israel: for learning about wisdom and instruction, for understanding words of insight …” (Prov 1:1–2). We will come to Proverbs in future weeks. Ecclesiastes begins, “The words of the Teacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem: ‘I, the Teacher, when king over Israel in Jerusalem, applied my mind to seek and to search out by wisdom all that is done under heaven’” (Eccles 1:1). Unfortunately, Ecclesiastes is set only once by the lectionary, in another season.

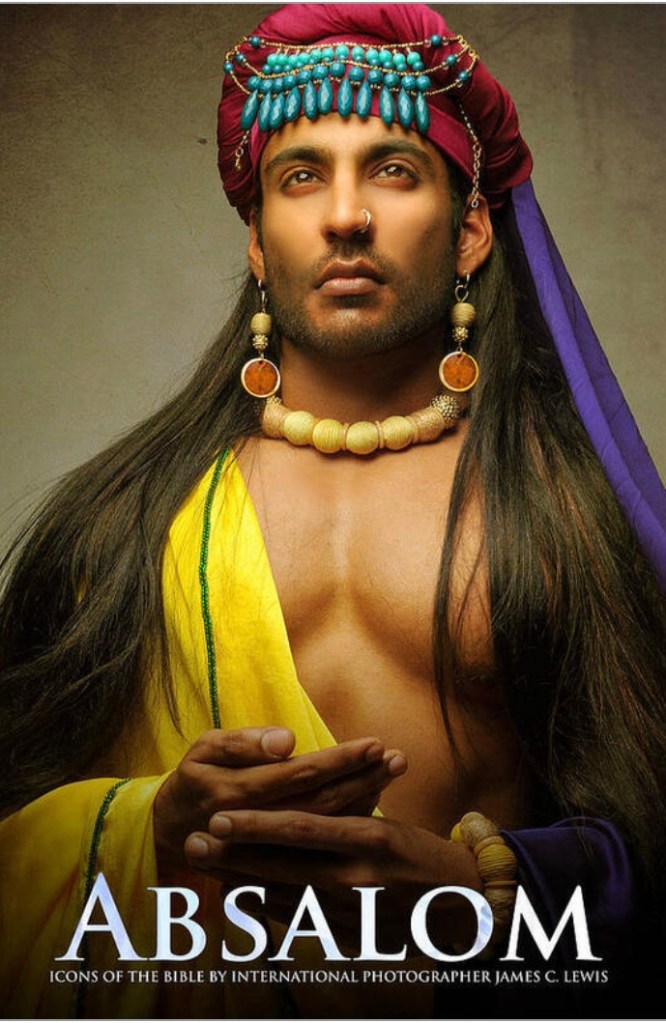

a miniature from the opening of Ecclesiastes (in Latin)

in the Bible of the Monastery of Santa Maria de Alcobaça, c. 1220s (National Library of Portugal ALC.455, fl.207).

Songs of Songs has the heading, “The Song of Songs, which is Solomon’s” (Song 1:1). We hear one short passage from the Song this coming Sunday; but the work deserves a longer introduction. Elizabeth and I have taught sessions on this book over the years, and she has written material from which I have drawn to develop the following blog, so I am grateful to her for a number of insights into this book.

The Song of Songs (also known as Song of Solomon) is one of the Hebrew Bible’s most beautiful texts; it is also highly controversial. The name itself suggests something grand; in true Hebraic style, the repetition of a word simply intensifies and magnifies the word. When God completed creation “and saw everything that he had made, and indeed, it was very good” (Gen 1:31), the Hebrew is tov tov (literally, “good good”). So the first two words of this book, shir ha-shirim, could well mean “the best of songs”.

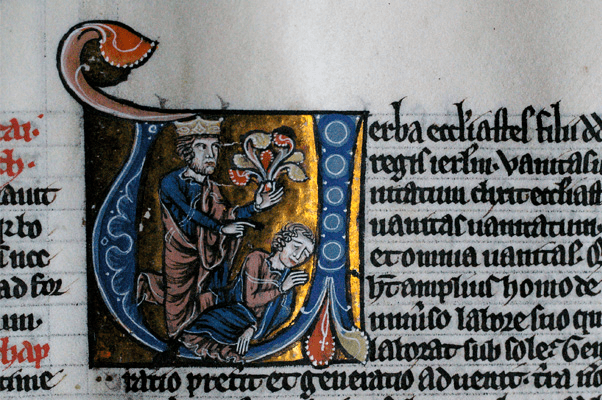

of The Song of Songs;;a minstrel playing before Solomon

(15th century Rothschild Mahzor)

Of course, numerous commentators have noted that there is no mention of God anywhere in this book; so that has raised questions about why it was included as one of the Megilloth in Kethuvim, the third section of the Jewish Torah; from which, it has been included in the Christian Old Testament. We know the rabbis debated this very issue; it was Rabbi Akiba who most strenuously argued for its inclusion (in tractate Yadaim 3.5, in the Mishnah). Akiba concluded that “the whole world is not as worthy as the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel; for all the writings are holy but the Song of Songs is the holy of holies.”

For many church fathers, the physical sexuality present in the Song made them quite wary of the book. They generally cautioned against reading it until a “mature spirituality” had been obtained, so that the Song would not be misunderstood and lead the reader into temptation. Origen wrote a commentary on the Song, allegorising throughout. The carnal, fleshy references were all considered to be analogies (or allegories) referring directly to spiritual, heavenly things. Origen was the master of allegorical meaning—something along the lines of “the text says ‘this’, but ‘this’ points to ‘that’, which is its deeper and intended meaning”.

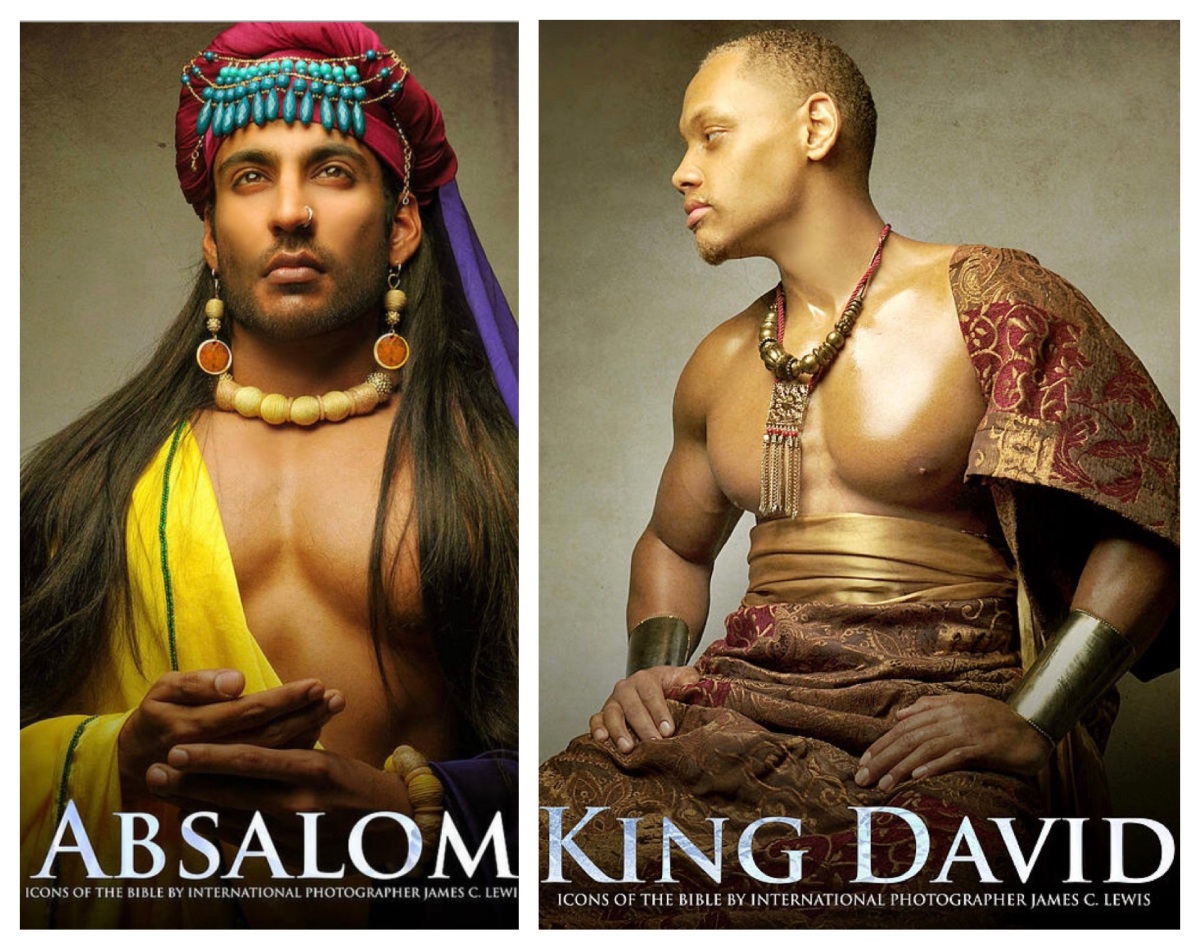

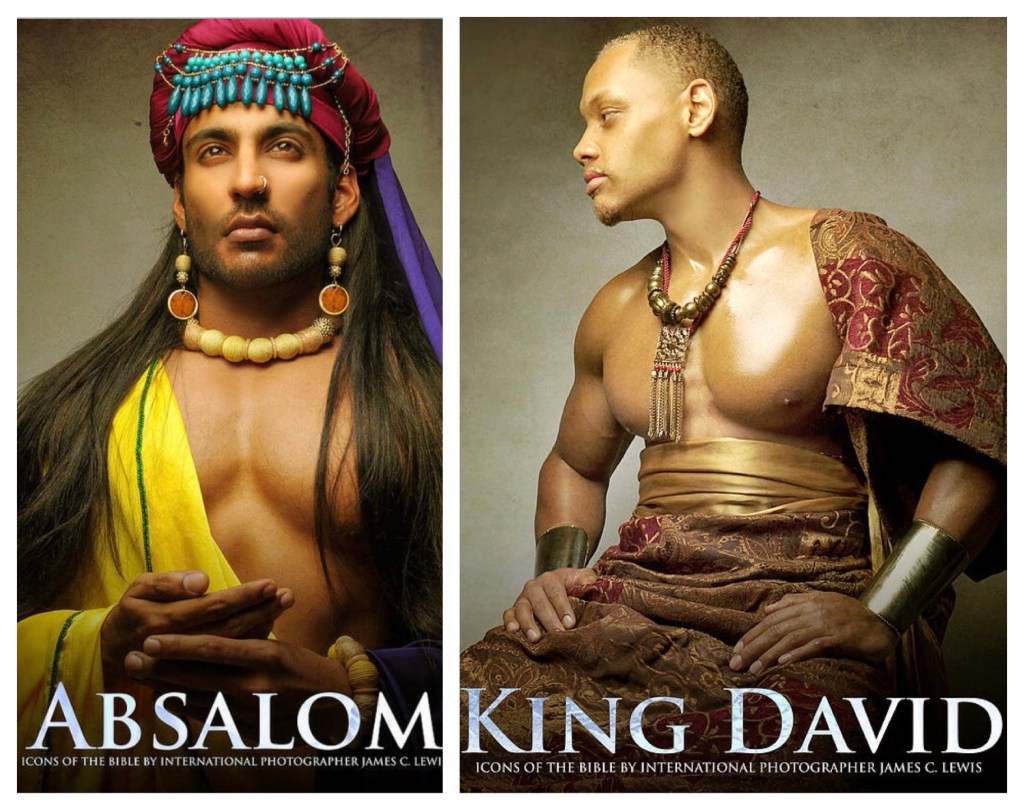

With God completely absent from the book, the two main characters are a man and a woman; the book contains a series of love songs between them, in which they express their love for one another in poetic form. The man is identified early on as the King (1:4, 12), and then explicitly identified as Solomon (3:9–11). Accordingly, the book has traditionally been identified as being by Solomon himself. In this view, perhaps, the wisdom of God might be conveyed in some way through his words?

However, scholars attempting to date the book disagree about this authorship, and have offered a wide range of possible dates for its composition. Because the Song contains elements characteristic of poems written in the courts of Egypt and Mesopotamia, could it be quite old? Does the dominance of an oral culture in antiquity mean that songs composed long ago were remembered and passed on by word of mouth for centuries before being written down? Could this mean the Song came from Solomon, or from his court?

Do the number of words that reflect an Aramaic influence point to a later origin of the Song in the period of the Exile onwards (from the 6th century BCE)? Was it a compilation made even later, after the exiles had returned and were firmly resettled in the land, in the 3rd century BCE, when other compilations of wisdom were being made? The debate continues.

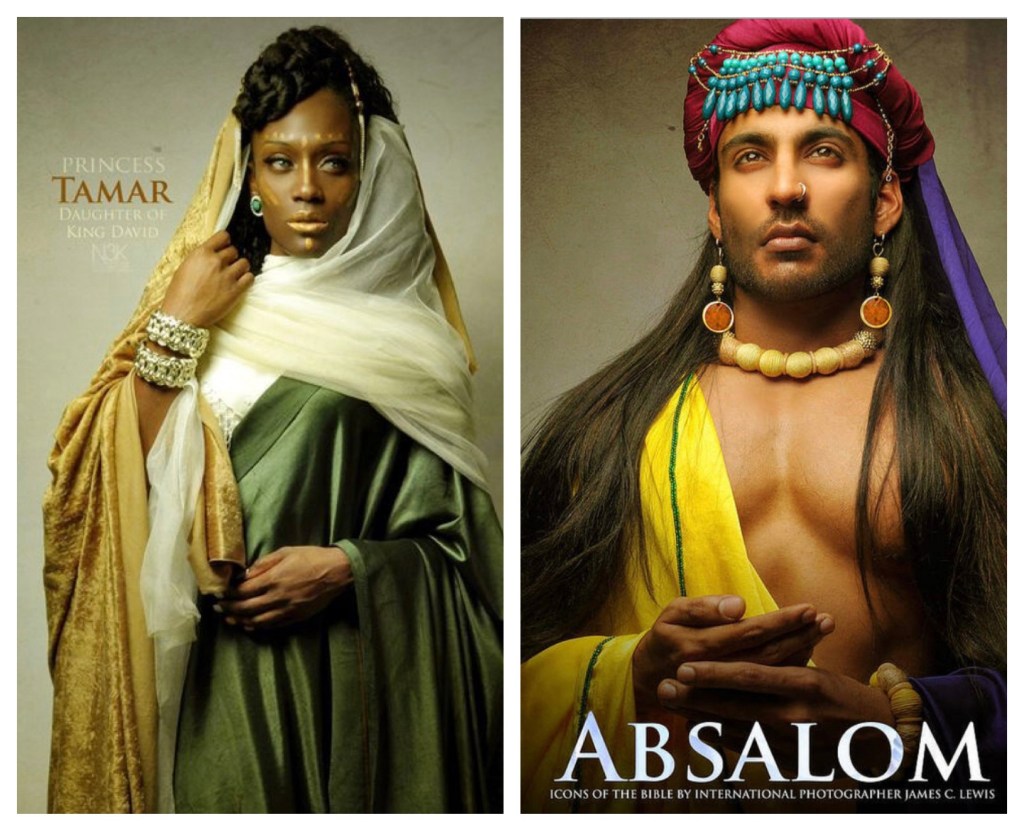

The woman character, described as “black and beautiful” (1:5), is later addressed as a Shulammite (6:13). Rabbinic interpreters, noting that her name means that she is “the one who brings peace” (8:10), relating her name either to shalom, peace (which is the basis for the name of Solomon himself). Other suggestions for her curious name identifies it with the village of Shunem or Shulem (the home of Abishag, King David’s beautiful attendant, 1 Ki 1:1–4); or the Mesopotamian war goddess Shulmanitu, who was perhaps also known as Ishtar.

by Gustavo Moreau, a 19th century French artist

It is notable that the woman plays a prominent role in this book; does she, perhaps, represent the female Wisdom character that is found in Proverbs and later wisdom literature? There is a suggestion from more recent commentators that, just as the book of Job was included in scripture to present an alternative view to the theology of Deuteronomy (God blesses the righteous and punishes the wicked), so the Song was included in the Hebrew canon to counter the many prophetic references which portray the idolatrous choices of Israel through the image of an adulterous woman. It’s an enticing possibility.

“Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth”, the Song begins, as the female character sings of her deep love for the king; “your love is better than wine, your anointing oils are fragrant, your name is perfume poured out; therefore the maidens love you!” (Song of Songs 1:1–3). Immediately the direct physicality of the poetry is evident. This continues right throughout the book.

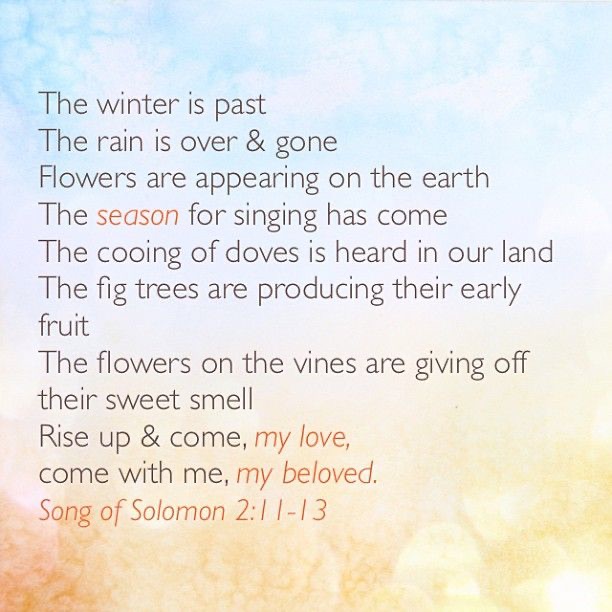

The passage proposed by the lectionary for this coming Sunday (Song 2:8–13) describes a wonderfully green scene, with springtime flowers reflecting the flowering of love that we can see in the poems. The lovers enjoy the beauty of Spring, which, for the young woman, is not unlike the beauty of her lover. The scene speaks of fertility, growth and beauty. Indeed, as one of the Megilloth (five short books, each read in full at a different Jewish festival), this book has been traditionally chanted by Jews each Passover, because of its thematic connection with springtime.

Back in the opening verses of the song (1:1–8), we have met the Shulammite princess who is in love with King Solomon; she is “black and beautiful” (v.5). She desires her lover’s kisses (v.2) and regularly addresses him as “my beloved” (1:13–14, 16; 2:3, 8–10, 16–17; 4:16; 5:2, 4–10, 16; 6:2–3; 7:11, 13; 8:14). She boasts to her handmaidens of his physical desirability, which they obviously find attractive: “your love is better than wine, your anointing oils are fragrant, your name is perfume poured out” (vv.2–3). Later she boasts that “my beloved is all radiant and ruddy … his head is the finest gold, his locks are wavy, black as a raven” (5:10–11). She tenderly describes his eyes, his cheeks, his lips, his arms, his legs, his body, and his sweet speech (5:12–16).

He, in turns, passionately admires his “fair one” (2:10, 13), describing her sweet voice and lovely face (2:14), telling her “how beautiful you are, my love, how very beautiful” (4:1) and exulting in her eyes, her hair, her teeth, her lips, her mouth, her cheeks, her neck, and her two breasts (4:1–5). Her love is “much better than wine” (4:10); he portrays her, modestly, as “a garden locked, a fountain sealed” (4:12) before more explicitly declaring, “your channel is an orchard of pomegranates with all choicest fruit” (4:13), “a garden fountain, a well of living water and flowing streams” (4:15). The language, poetic and lyrical, conveys a deep-seated erotic feeling.

The explicit nature of the relationship is continued in the ensuing poem of the princess; “I had put off my garment”, she says; “I had bathed my feet … my beloved thrust his hand into the opening and my inmost being yearned for him” (5:4). So, she says, with her fingers and hands dripping, “I opened to my beloved” (5:6). But he had disappeared; she was “faint with love” (5:8)—and then, “my beloved has gone down to his garden, to the bed of spices, to pasture his flock in the gardens and to gather lilies” (6:2). He flatters her; “you are beautiful as Tirzah, my love, comely as Jerusalem” (6:4), continuing with words of praise for her feet, her thighs, her navel, her belly, her two breasts, her neck, her eyes, her nose, and her hair (7:1–5).

“How fair and pleasant you are, o loved one, delectable maiden” (7:6), he sings, returning again to her breasts and her kisses (7:8–9). So, at last, he invites her “into the fields, to the vineyards”, to see ”whether the vines have budded, whether the grapes blossoms have opened and the pomegranates are in bloom” (7:11–12). It is, finally, a scene of consummation; “there I will give you my love” (7:12).

The Song ends with a statement of complete and total commitment, when the woman says to the king, “set me as a seal upon your heart, as a seal upon your arm” (Song 8:6). This refers to the practice of stamping a seal over a document to show that it is legally enforceable.

Hebrew Scripture refers to the seal of King Ahaz of Judah (1 Ki 21:8) and Ahasuerus, king of the Medes (Esther 8:8). A seal was the size of a fingertip, made of stone or bone, engraved with a figurative design. It was a precious personal item for people of high status; so the woman in these songs is indicating that she wishes to be a precious personal part of the king’s life. (Elizabeth and I used these words in our wedding vows to each other, to indicate the same thing.)

The songs of this book end with the woman’s plea for the man to come quickly to her; “make haste, my beloved” (8:14) signals her aching desire for her lover. From beginning to end, this book is saturated with deep-seated longing, with unfettered desire, and unbounded hope.

Are the words of this poetry to be interpreted literally; are they actual words of a king, yearning for his lover, and the responses of the lover of the king, yearning for his touch (and more)? Or is there another level of meaning? The explicit erotic language of this poetry has sent shivers of horror down the spines of interpreters, from antiquity through to modernity. How could such poetry be considered to be “the word of the Lord”?

Our response to that question, it seems to me, is governed by the way that we view this material world. Is it an evil, unredeemed prison, from which we must seek release? Or is it the creation of a deity who has embued all physical matter with a spark of divinity? If it is the former, then this earthy, sensual language must point beyond, to a spiritual dimension; we are to interpret it as symbolic of God’s heavenly realm. If it is the latter, we are to accept and rejoice in the literal meaning of the poetry.

My view is that there is nothing at any point throughout these Hebrew songs which gives any clue at all that we are to interpret them in a “spiritualised” manner, as so many have done. Throughout ancient Israelite texts, and on into Second Temple Judaism and then Rabbinic Judaism, material things are good, valued, and to be enjoyed. It is only the deep-seated teaching of hellenistically-inspired interpreters, schooled in the Platonic view that the spirit is good but the flesh is evil, that points in such a direction. Instead, we must surely accept that the abundantly erotic and exuberant language in these songs must be taken precisely in that fashion: as a celebration of earthly, material sexuality.

There is an abundance in the language used throughout the Song of Songs. Abundance was celebrated in ancient Israelite society—especially abundance in material, physical elements. The spirit-inspired Balaam forsees that for Israel, “water shall flow from his buckets, and his seed shall have abundant water, his king shall be higher than Agag, and his kingdom shall be exalted” (Num 24:7). When David’s troops came into Hebron to celebrate David’s accession to the throne, their neighbours brought “abundant provisions of meal, cakes of figs, clusters of raisins, wine, oil, oxen, and sheep, for there was joy in Israel” (1 Chron 12:40).

The prophet Ezekiel declares that God promises the exiles of Israel, “I will summon the grain and make it abundant and lay no famine upon you. I will make the fruit of the tree and the produce of the field abundant” (Ezek 36:29–30), while Joel rejoices, inviting the children of Zion to “be glad and rejoice in the Lord your God; for he has given the early rain for your vindication, he has poured down for you abundant rain, the early and the later rain, as before” (Joel 2:23). Speaking through a later prophet, the Lord invites people to “come to the waters … come, buy wine and milk without money and without price … eat what is good, and delight yourselves in rich food” (Isa 55:1–2).

The psalmists rejoice in God’s “abundant goodness” (Ps 31:19; 145:7), “abundant mercy” (Ps 51:1; 69:16), that God is “abundant in power” (Ps 147:5), promising that “the meek shall inherit the land and delight themselves in abundant prosperity” (Ps 37:11). One writer rejoices that, year after year, the Lord “crowns the year with [his] bounty”, singing that “you visit the earth and water it, you greatly enrich it; the river of God is full of water; you water its furrows abundantly, settling its ridges, softening it with showers, and blessing its growth” (Ps 65:9–11).

This physical imagery of abundance is strongly evocative of the joyful Spring scene in Song of Songs that we hear this Sunday: “the flowers appear on the earth; the time of singing has come, and the voice of the turtledove is heard in our land; the fig tree puts forth its figs, and the vines are in blossom; they give forth fragrance” (Song 2:12–13).

In his exploration of this book, Tom Gledhill remarks on the imagery of the man bounding through the countryside and calling the woman out of her home to join him in the explosion of nature in springtime as part of a recurrent theme in the Song: “The rural countryside motif is an expression of untrammelled freedom and exhilaration, of energetic enthusiasm and adventure, travelling new and unexplored pathways, taking the risks that a new liberty entails.”

Gledhill notes that “the tiny spring flowers are sparkling forth amongst the new shoots of the undergrowth … there is a hint of future blessings in the references to the fig tree and the vines in blossom. Our lovers are part and parcel of this explosion of new life and new hope.” (The Message of the Song of Songs, IVP, 1994, pp. 132–133). Is this perhaps a pointer to the divinity that these poems are making? — a pointer to the deity who creates the world and oversees the cycles of fertility and abundance?