This coming Sunday, the lectionary offers the one and only chance in three years to hear from the book of Esther. (The passages offered are Esther 7:1–6, 9–10; 9:20–22.) There is a lot to note in considering this story, so I am devoting two blogs to it. In Part One I considered the historical and social context. Part Two (this blog) now explores theological issues which are embedded in this story.

This material was originally developed by my wife Elizabeth Raine and myself in the course of teaching a whole course on the Wisdom Literature; you can watch videos of the various sessions at

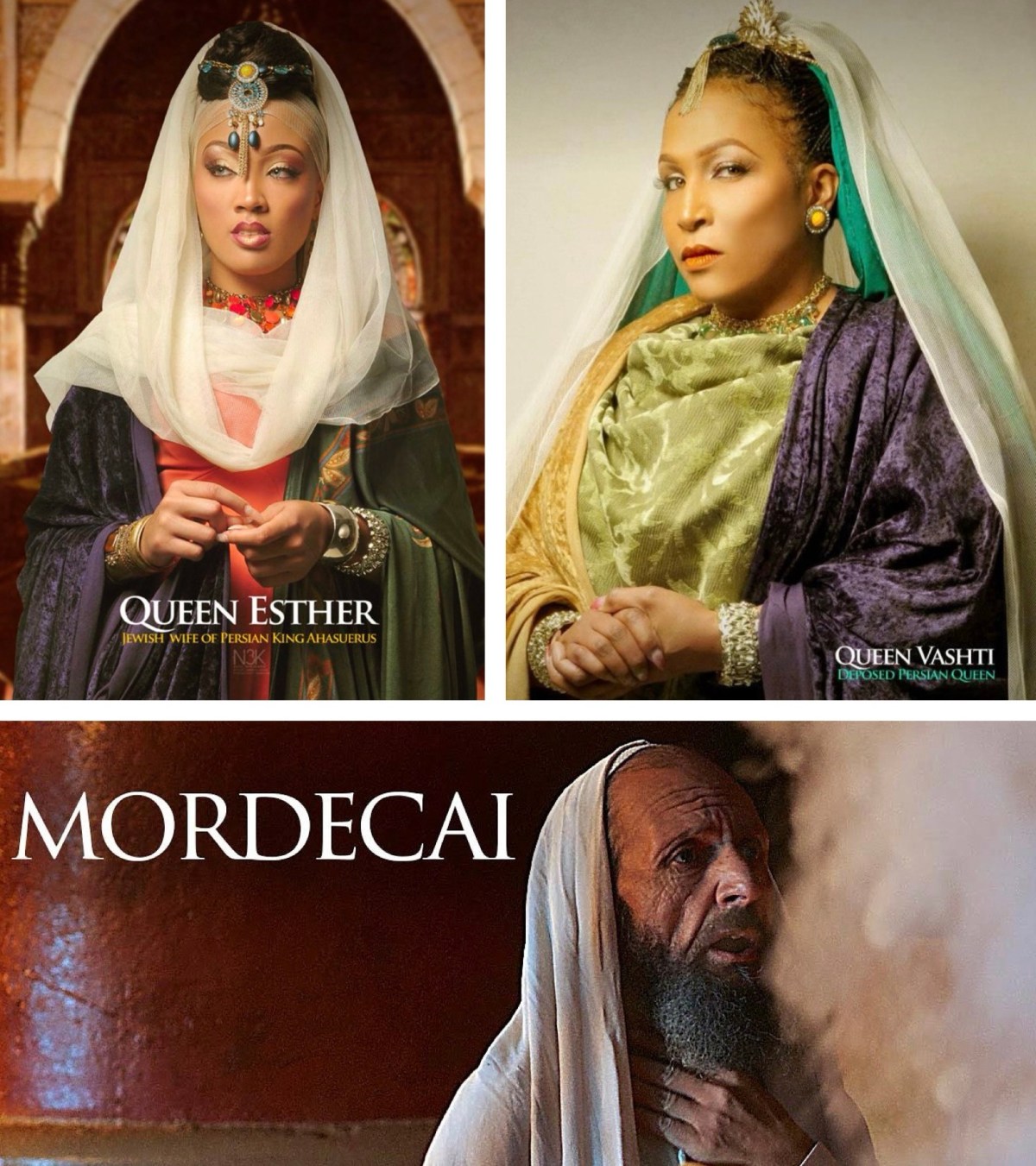

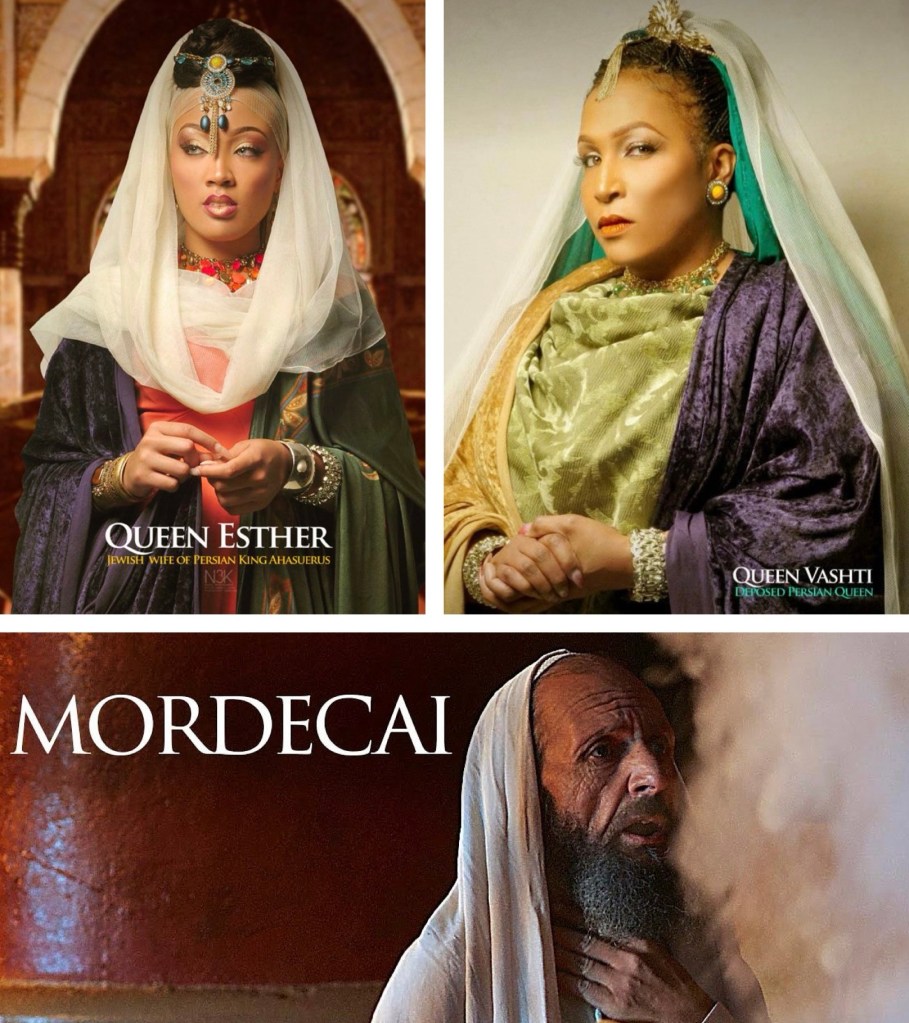

The book of Esther tells the story of how two wise and courageous Jews, Mordecai and Queen Esther, aided by the providential hand of fate, foil the genocidal schemes of Haman, the “enemy of the Jews”.

Jewish identity is a key issue in this story. Vashti refuses to appear before Ahasueris “wearing the royal crown, in order to show her beauty” (1:11). The rabbis later interpret this to mean “wearing only the royal crown”—that is, stark naked except for the crown! Esther then takes part in a “beauty contest” (2:1—4) which involves not only parading before the king, but “pleasing the king” (2:4)—an explicitly sexual activity (see 2:13—14). Esther is chosen to be the Queen (2:17). But there is a crucial element in the story that occurs when Esther, taking the advice of Mordecai, decides to hide the fact that she is Jewish (2:20).

So Esther stands as a symbol of Jews who lived successfully in an alien culture. As a woman, she was not in a position of power, just as Diaspora Jews were not members of the power elite (although when she marries the King, and becomes Queen, she does acquire power). As an orphan, she was separated from her parents, as Diaspora Jews are separated from their mother-country. With these handicaps, she had to use every skill and advantage she had, as Diaspora Jews did. They, like Esther, had to adapt themselves to the situation.

Israelites and Canaanites are each signalled within this story. Haman, an Agagite, is a descendant of the people of Canaan (3:1), later described as “the enemy of all the Jews” (3:10; 9:24). He is descended from Agar, King of the Amalekites, whom the men of Saul (an ancestor of Mordecai) had defeated (1 Sam 15:1—9), in obedience to the word of the Lord, “attack Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have; do not spare them” (1 Sam 15:3).

The bad behaviour of Haman in the story of Esther (chs.3—5) is met by the resolute intransigence of Mordecai. He is not going to give way; when Haman presses the point, Mordecai stands up to him. Just as his ancestor, Saul, had fought against the Amalekites, so Mordecai opposes Haman. He will not let him have his way.

The story offers a striking portrayal of just how the Israelites perceived the Canaanites. It offers food for thought in the conflicted and increasingly difficult situation in modern Israel, where the “Canaanites” or “Amelakites”—modern- day Palestinians—are viewed with intense suspicion. Indeed, the government of the modern state of Israel appears utterly focussed on “extermination” as the fundamental policy with regard to the Palestinians. (I note that last year, Prime Minister Netanyahu was reported to have said that Israel is “committed to completely eliminating this evil from the world,” adding “you must remember what Amalek has done to you, says our Holy Bible. And we do remember.”)

In the Additions to Esther, Haman is further described as “Haman son of Hammedatha, a Bougean” (3:1; 12:6). Bougean is believed to be a term of shame and disgrace (its precise origin is unknown.) A variant text calls him a “a Macedonian”, clearly reflecting the dominance of the empire established by Alexander the great, a Macedonian, from 334 BCE onwards.

Kingship is also an issue in this story. The absolute power of kings in the ancient world seems strange to us, accustomed as we are to the democratic rule of law. But in many parts of the ancient world a king was thought of as a living god. He was a sacred person who embodied, in his person, the state or kingdom that he governed. His physical body was clearly not immortal, but he was thought of as someone who was more than human, with a special and unique connection with the immortal gods. Because of this, he could do what he wanted even when, as in this case, it was clearly unjust.

It is true that Israel had kings. However, they believed that the King served God, who was the true King; and every King was held to account by a Prophet, who declared “the word of the Lord” to the King. When it did have great kings like David or Solomon, it emphasized their humanity. In the Israelite mind, kingship was very close to tyranny, and had to be constantly hedged around with precautions to stop it becoming despotic.

Esther as comedy? This is a serious suggestion! The story told in Esther contains many of the stereotypical characters that appear in vaudeville, burlesque, or farce—there is a hero, a fool, a beautiful heroine, and a bad guy. One commentator says, “all the characters are types; the largest interpretative problems melt away if the story is taken as a comedy associated with a carnival-like festival” (A. Berlin, Esther, JPS, 2001). What do you think about characterising this book as a comedy?

Finding where God is at work is another theological issue that this story addresses. God is not explicitly mentioned in the story of Esther. There may be some places where you might think that God is at work in what transpires (for example: “the roll of the dice”, the fasting of the Jews, and the many coincidences in the story). But this is implied, not explicitly stated. As you read the story, how might you hear the invitation to “find ways that God is at work in what happens”? (There are resonances, perhaps, with the claim that is often made today, that “God’s mission is in the world” and so the call to the church is to “seek out ways that God is at work in the world and join with God in that work”.)

So why is Esther in the canon? We might note some problems: There is no mention of God—Neither Esther nor Mordecai seem to follow Jewish Law—Esther is married to a Gentile—Esther does not follow the food laws of Leviticus (she eats non-kosher food)—The account of Purim does not mention prayers, sacrifices, or any religious ceremony

But there are also some positives: The story is set in the Dispersion, outside of Israel—Esther appears powerless but is able to achieve her goal—Esther offers a positive role model for living successfully in the Dispersion—Purim celebrates the ingenuity of a wise woman in a foreign place

So do you think it is a good thing that Esther is in the canon of scripture??

The Additions to Esther. The book of Esther exists in Hebrew Scriptures in its Hebrew original. In the Roman Catholic scriptures, there is a longer version of Esther which contains six so-called Additions. This version is written in Greek and is 150 verses longer. This longer version ends, “In the fourth year of the reign of Ptolemy and Cleopatra, Dositheus, who said that he was a priest and a Levite, and his son Ptolemy brought to Egypt the preceding Letter about Purim, which they said was authentic and had been translated by Lysimachus son of Ptolemy, one of the residents of Jerusalem.” (11:1).

In the Additions to Esther, the extra verses provide more character development, supply information missing from the Hebrew text, and add an explicit religious dimension—God is mentioned at 2:20; 4:8; 6:1, 13. It is clear that the Jews are saved by God. God works primarily through Mordecai. Esther becomes the romantic heroine of the sideline plot, not the centre-stage star.

Finally: how might Esther relate to Lady Wisdom? The book of Proverbs portrays Wisdom in ways that show she can operate well in “ordinary, everyday life”. Esther and Mordecai operate in the messy circumstances of the royal court of Persia. They manage to find a way through the situations they face which works out well in the end. Is this a valid connection?

Looking back over the story, we can see that the book tells a story that is not located in Israel, about morally compromised people, with no active involvement in the story by God. How do we understand it?

From the point of view of a Jew living in the Diaspora, the story ends on a positive note. Mordecai has an influential position (10:3). Persian records include positive references to the Jews (10:2). Future generations of Jews celebrate Purim (9:26-32). It assures the people of Israel that God is with them, even when they are living in exile, even when they are acting in morally compromised ways.

From the point of view of a Jew living in Israel, there are no references to the rebuilding of Zion (Ps 102:16), no indication that the nations will come to Zion to worship the God of Israel (Isa 60:1-3). The future of the Jews appears to lie in the capricious and untrustworthy hands of the Persian Empire. It displays the precarious nature of Jewish identity, and the fact that the fate of being a Jew lies in foreign control.

What do you think?