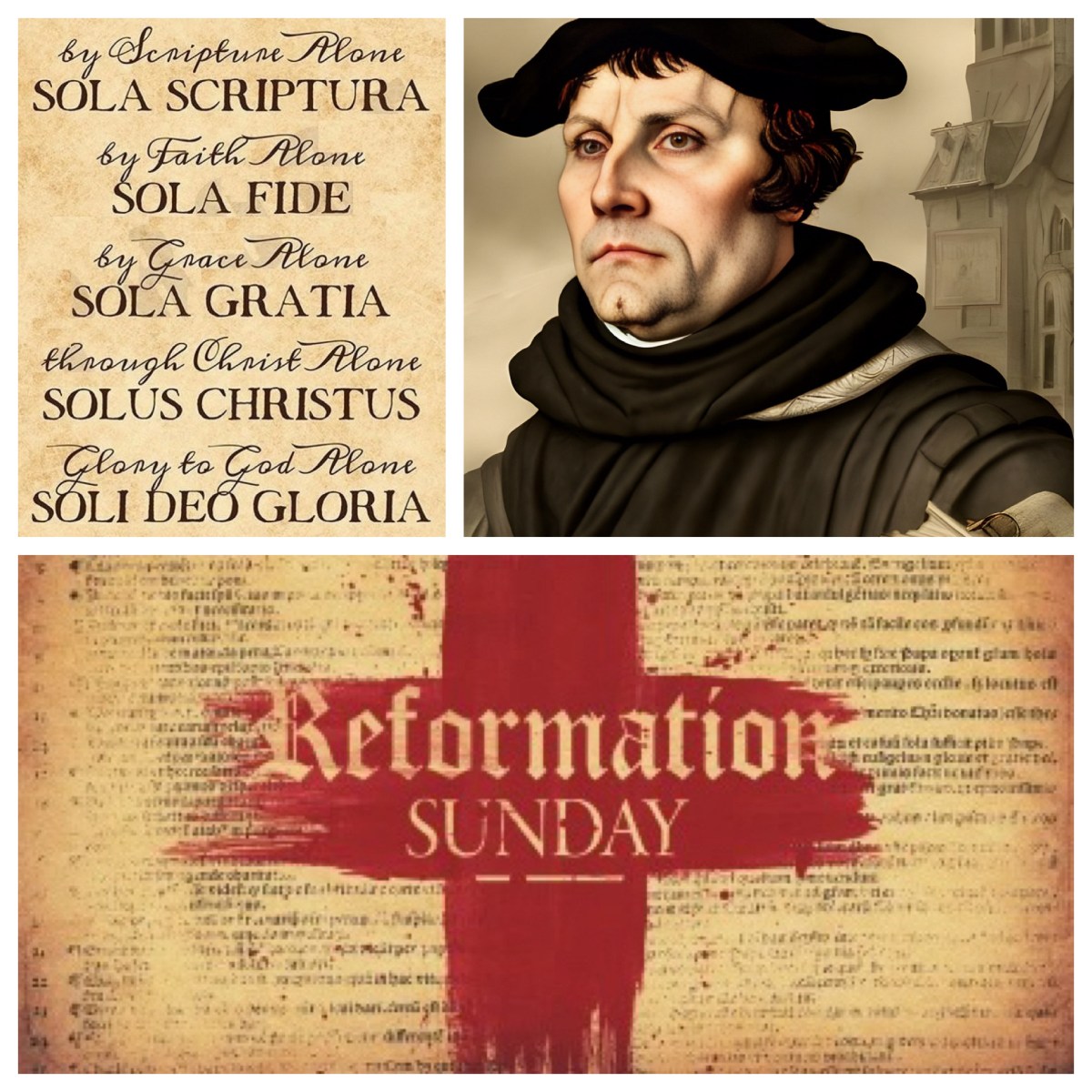

On the last day of October each year, churches in the Reformed tradition celebrate Reformation Sunday. 31 October is chosen to remember the day, in 1517, when Martin Luther “nailed his theses” to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg in Saxony. That action is widely regarded as “the start of the Reformation”, which saw many churches in Europe separate from Roman Catholicism, the dominant expression of Christianity across Europe.

Of course, historians today note that there had been earlier movements which led to the reformation of assorted churches, led by John Wycliffe in England and Jan Hus in Bohemia. But it is Martin Luther in Germany, along with later figures such as Frenchman Jean Calvin, Scotsman John Knox, and Ulrich Zwingli in Switzerland, who are regarded as key figures in the various Reformations that took place. (And in England, the actions of King Henry VIII, driven by his peculiar personal needs, must also be considered; although whether the Church of England is formally a Reformed church is hotly contested!)

Cheery bunch, aren’t they?

Reformed Churches share much with other branches of Christianity, as well as having certain distinctives which set them apart. One of those key distinctive s has to do with the centrality and overarching significance of scripture in the life of the church. So in this post I aim to set out what I consider to be ten key aspects of Christianity, with some observations about how they might be seen to derive from biblical texts—although I think the actual relationship in each case is more complex and sophisticated than just quoting a couple of “proof texts”.

So, here is my take on Ten Things about the Christian Faith that I think are significant. I will,explore, in this post, Jewish heritage, Hellenistic contextualisation, and a state religion leading to Christendom. In the next post, I will consider various influences on theology over time, the central tension of words and deeds, the growing dominance of the Global South, and Eastern Orthodox commitment to tradition and creeds. In the third post, my attention turns to post-Christendom weakening in the West, ecumenical and interfaith developments, and bearing witness to faith in sensitive ways for the present.

I

Our Christian faith does not exist in a vacuum. For a start, it draws on the long heritage of Judaism, from the sagas telling of ancient days in Mesopotamia and Canaan, through the development of Israelite society, culture, and religion, listening to the voices of prophets and sages, on into the period of the Second Temple, laying the foundation for Judaism itself, and including then the time when Jesus, James, Paul, and others lived. All of these Jewish elements have influenced and shaped elements of the Christian faith.

The clearest example of this must surely be when Jesus is asked “which commandment is the first of all” (Mark 12:28). Jesus draws from his Jewish heritage, quoting, “you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind” (Deut 6:5), and then following up with a second commandment, also from Hebrew scripture, “you shall love your neighbour as yourself” (Leviticus 19:8).

Another striking instance comes at the start of Paul’s major theological statement, his letter to the Romans. In this letter he sets out the message about the gospel that he preaches, declaring that it is “the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek” (Rom 1:16). His summary of that gospel, “in it the righteousness of God is revealed through faith for faith”, is based on words from a minor Israelite prophet, Habakkuk, who declared, “The one who is righteous will live by faith” (Rom 1:17, citing Hab 2:4b).

There are many other instances which could be cited to show how Hebrew scripture and Israelite religious practices are at the heart of the books of the New Testament. Amongst the reformers, the Hebrew Scriptures have an assured place in the canon—although Luther was renowned for his vituperative criticisms of Jews and Judaism. (They misunderstood God and faith, he maintained.) Overall, the way that Hebrew Scriptures provide a bedrock for later developments in Christian thinking is clear to the key reformers.

II

Those developments are evident to modern interpreters in the ways that the books of the New Testament expressed faith. The second testament provides the first example of how Christian faith has been contextualised in different ways in various eras. New Testament Gospels and Letters and many of the patristic works in ensuing centuries have been influenced by the philosophical wisdom and rhetorical finesse which dominated the Hellenistic world. The interplay between the heritage and traditions of Judaism and the culture and practices of Hellenism is an important dynamic within these writings. Awareness of this interplay when reading any particular passage can lead to a deeper understanding of its message, as the word of God for their time and for our time. In making that affirmation, the claim of the centrality of scripture made by the reformers is being drawn upon.

An obvious illustration of the interplay at work in contextualisation is the contrast between two speeches of Paul, which are reported in Acts. Speaking in a synagogue to a Jewish audience in Antioch of Pisidia, Paul refers, understandably, to the Hebrews Scriptures (Acts 13:33–41). A week later, he quotes Isaiah 42:6; 49:6 (“a light for the Gentiles”) (Acts 13:46–48).

In Athens, by contrast, speaking at the Areopagus to a group of Greek philosophers, Paul draws from “some of your own poets” (Acts 17:28) when he quotes from Cretica by Epimenides (“in him we live and move and have our being”) and then a line found in the Phaenomena by Aratus (“we are also his offspring”). What is quoted depends on what the audience knows; a simple indication of how contextualisation works.

III

The development of Christendom through the positioning of Christianity as the state religion of Roman society, from the fourth century onwards, has left an indelible mark on Christianity. For centuries after Constantine adopted this religion, Christian leaders have considered Christianity to be The State Religion. This has been the case in societies in many places and later times, especially in a number of European countries and their colonies. Even in the Reformation, the creation of new churches did not mean that there was a break between the State and the new Church. Lutheranism, and a number of other Reformed Churches, became the State religion of their countries!

The dynamic of how the Christian faith relates to the formal structures and patterns in governing society is thus a factor which has shaped and informed expressions of Christianity over the centuries. Words of Paul in his letter to the Romans are often cited as the basis for this development: “let every person be subject to the governing authorities; for there is no authority except from God, and those authorities that exist have been instituted by God” (Rom 13:1). That’s a somewhat simplistic application of this text to later situations. Even this longest letter of Paul, often regarded as his theological magnum opus, was contextual and contingent, as chapters 14—16 demonstrate.

Alongside this, a later letter claiming the authority of Paul speaks of a struggle “against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (Eph 6:12), while the final book of the New Testament provides a vivid, dramatic polemic against the Roman Empire, portrayed as “the great whore who is seated on many waters, with whom the kings of the earth have committed fornication, and with the wine of whose fornication the inhabitants of the earth have become drunk” (Rev 17:1–2). Church—State relationships are complex.

… more to come …

… and still more …