This blog explores the passage which the Narrative Lectionary offers for this Sunday (1 Kings 17:1–24), in which the prophet Elijah is introduced. But let me begin with Jesus.

Jesus was a Jew, raised in the manner of his time, taught to read Torah, the scrolls which held prime place in his religion. He was schooled in the detailed requirements of the Law which expressed commitment to the covenant made by the Lord God with ancestors of old (Noah, Abraham, Jacob, David). He actively participated in the practice of prayer and study which occurred in the synagogues and the rituals of offerings and sacrifices that took place in the Temple in Jerusalem.

As an adult, Jesus broke with his family and began to exercise an itinerant ministry, travelling from place to place with a small, but growing, group of followers, dependant upon the hospitality of those who welcomed him to the villages and towns he visited. In this regard, Jesus was following the practice of prophets in the traditions of the Israelites who travelled from place to place, not settling anywhere. Both Elijah and Elisha lived in this manner; Elijah was known as “hairy man, with a leather belt around his waist” (2 Ki 1:8).

This mode of living, of course, was adopted by John the Baptist, who was “clothed with camel’s hair, with a leather belt around his waist, and he ate locusts and wild honey” (Mark 1:6). And, of course, there are indications that Jesus—and some of his own disciples—had been followers of John before he launched into his own public mission. Jesus continued the message proclaimed by John, to “repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (Matt 3:2; 4:17) and he continued the emphasis of John to “bear fruits worthy of repentance” (Matt 3:8–10; 7:17–20) and to share one’s own clothing and food with others who are lacking these essentials of life (Luke 3:11; 12:42; and see Matt 25:34–40).

For more on how Jesus and John are related, see the groundbreaking work of Prof. James McGrath in Christmaker, which I have reviewed at

As an adult, Jesus travelled from village to village, preaching his intense message that “the kingdom of God” was drawing near, fervently calling people to repent of their sins and commit completely to the ethical way of living that Torah required. It was all in for Jesus, both in terms of what he preachers, and in terms of how he lived—there was no halfway point for him!

In this regard, Jesus shared the key characteristics of a wild-eyed, desert-dwelling, fiery apocalyptic preacher, vigorously proclaiming the imminent coming of the reign of God. This itinerant, apocalyptic Jesus was resolutely Jewish, standing in the tradition of a string of earlier wild-eyed, rhetorically powerful prophetic figures: Elijah, Nathan, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Joel, Malachi—and his own relative and mentor, John the baptiser.

It is Elijah the Tishbite whom we meet in the passage which the Narrative Lectionary offers for this Sunday (1 Kings 17:1–24)—Elijah, who is later described as “a hairy man, with a leather belt around his waist” (2 Ki 1:8). This initial portrayal of Elijah is nested within the accounts of that long period of time when Israel was ruled by kings, when prophets functioned as the conscience of the king and the voice of integrity within society.

Elijah operated during the period when Ahab ruled Israel; he figures in various incidents throughout the remainder of 1 Kings—most famously, in the conflict with the prophets of Baal which came to a showdown on Mount Carmel (1 Ki 18), and then later in his confrontation with Ahab and his wife Jezebel, over the matter of Naboth’s vineyard (1 Ki 21). Like Jesus, Elijah was no shrinking violet!

Elijah first appears in the narrative of kings, seemingly out of nowhere, at the beginning of this lectionary passage (1 Ki 17)—just as he disappears from sight when he hands over his role to his successor, Elisha, and as “a chariot of fire and horses of fire separated the two of them”, Elijah ascends in a whirlwind into heaven (2 Kings 2:1–15).

So in 1 Kings 17, Elijah predicts a drought and takes himself into the desert, where ravens fed him food and he drank from the wadi, until the wadi dried up (vv.1–6). Elijah did as he was commanded and travelled out of Israel, to the neighbouring region of Sidon (v.7). Is this start of Elijah’s public activity mirrored, centuries later, in the account of Jesus retreating into the wilderness near the Jordan, before his public activity got underway?

However, whilst Jesus meets the tempter, Elijah meets a widow who, despite being unnamed, is nevertheless well known in Christian circles because Jesus himself, according to Luke, refers to her in a keynote sermon. This took place when he came to his hometown on Nazareth, and was given opportunity to speak in the synagogue (Luke 4:14–30). After reading from the scroll of Isaiah, Jesus refers to stories of two prophets—Elijah and Elisha—and honours this particular widow amongst “the many widows in Israel at the time of Elijah” (Luke 4:25–26). These verses form the short subsidiary reading which the Narrative Lectionary places alongside 1 Kings 17.

The widow offers hospitality to the prophet. Hospitality was a fundamental cultural practice in ancient Israel; there are many stories of the hospitality offered by people such as Abraham (Gen 18:1–15), Rahab (Josh 2:1–16), and David (2 Sam 9:7–13), and hospitality offered earlier to Moses in Midian (Exod 2:15–25), here to Elijah in Zarephath (1 Ki 17:10–24), and later Elijah in Shunem (2 Ki 4:8–17). Welcoming hospitality is commanded in relation to aliens in Israel (Lev 19:33–34) and is advocated in relation to exiles returning to the land (Isa 58:7). The passage from 1 Kings 17 that is proposed by the Narrative Lectionary well exemplifies this practice. The widow had very little; and yet she finds enough to provide for Elijah, in a display of warm hospitality to this foreign Israelite in her territory.

Hospitality had a fundamental significance in the cultural practices of the day. Writing in Bible Odyssey, Peter Altman notes that “hospitality serves as an underlying core value for how the characters in the Hebrew Bible should treat others, for they, too, understood the precarious nature of life as an outsider”.

See https://www.bibleodyssey.org/articles/hospitality-in-the-hebrew-bible/

In the same resource, Carolyn Osiek notes that this value continues strongly throughout New Testament books, which are “full of images and stories of guests received, both those already known as friends and those strangers who are taken in and transformed into guests. Among nomadic tribes, the guest comes under the protection of the host, who guarantees inviolable safety. The important elements of hospitality include the opportunity for cleansing dusty feet, scented oil to soften dried skin and mask odors of the road, food, shelter, security, and companionship.”

See https://www.bibleodyssey.org/articles/hospitality-in-the-new-testament/

Gerd Theissen, a German New Testament scholar, has proposed that the message of Jesus was spread by itinerants within the early Jesus movement who travelled from village to village with their message. They were dependent on those who received them for hospitality and lodging, in literal obedience to what Jesus had told his disciples (Mark 6:10–11; see also Matt 10:41 and Didache 11:1, 4–6). Jesus and his followers were living in complete obedience to “the Son of Man [who] has nowhere to lay his head” (Matt 8:20; Luke 9:58). In a sense, they are also continuing the pattern which we see in this story of Elijah, as he travels to Sidon during the famine, receiving hospitality from the widow of Zarephath.

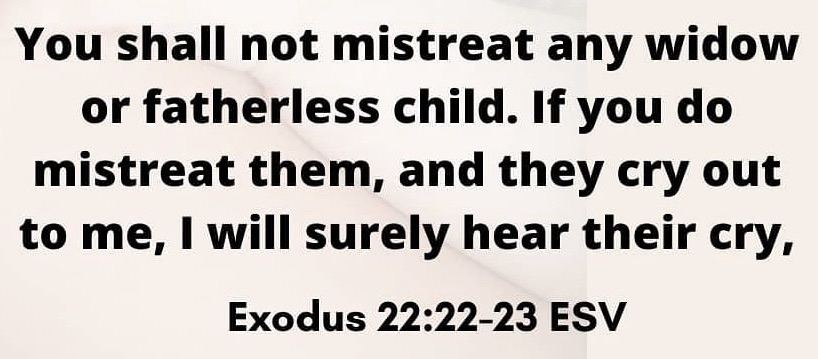

Widows in ancient Hebrew society were in a perilous position. In a strongly patriarchal society, the patronage of a man was vital: a man as husband and provider, a man as father and protector, a man as the household head. Children without fathers—orphans—as well as women without husbands—widows—were in equally perilous situations. They were vulnerable people, often at risk of being mistreated and exploited, of being pushed to the edge of society and being forgotten. They could well be the desolate who needed housing (Ps 68:6).

In the Hebrew Scriptures there are regular exhortations and instructions to the people to take care of widows and orphans, the key classes of vulnerable people in that society: “you shall not mistreat any widow or fatherless child” (Exod 22:22) and the instruction to gather a tithe of produce and invite “the Levite, the foreigner, the fatherless, and the widow to come and eat and be filled” (Deut 14:28–29). Even in ancient society, vulnerable people needed protection.

More that this, the Torah provides that the widow and the fatherless child were to included along with the sojourner in celebratory moments in Israel, at the Feast of Weeks (Deut 16:9–12) and the Feast of Booths (Deut 16:13–15). This was also to be the practice when the men were in the field harvesting; they were to leave some for gleaning by ”the alien, the orphan, and the widow” (Deut 24:19–22); and similar prescriptions govern the time when tithing (Deut 26:12–13; also 14:28–29).

Not everyone adhered to these prescriptions. Among the prophets, Isaiah proclaims God’s judgement on those who “turn aside the needy from justice … and rob the poor of my people”, including the way that they exploit the fatherless and widows (Isa 10:1–2). Likewise, Ezekiel includes those who “have made many widows” in Israel amongst those who will experience the full force of God’s vengeance (Ezek 22, see verse 25). He observes that “the sojourner suffers extortion in your midst; the fatherless and the widow are wronged in you” (Ezek 22:7). Jeremiah encourages the people of Jerusalem with a promise that God will allow them to continue to dwell in their land if they “do not oppress the sojourner, the fatherless, or the widow, or shed innocent blood in this place … or go after other gods” (Jer 7:5–7).

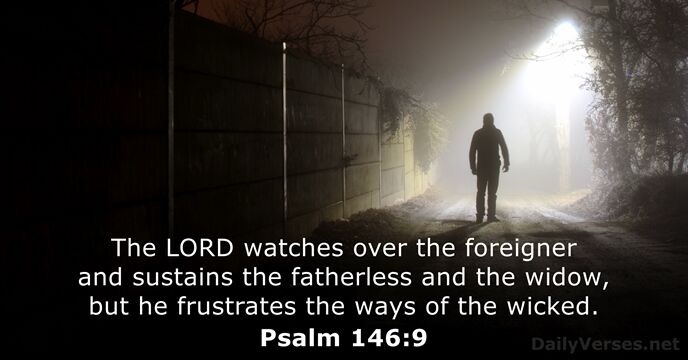

Accordingly, the people of Israel would regularly have sung, in the words of the psalmist, “the Lord watches over the sojourners; he upholds the widow and the fatherless, but the way of the wicked he brings to ruin” (Ps 146:9). Care for widows was central to the life of holiness required amongst the covenant people. This psalm reminds them of that claim on their lives.

And so the brother of Jesus, James, writes that “religion that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is this: to care for orphans and widows in their distress, and to keep oneself unstained by the world” (James 1:27), summing up a strong thread running through Israelite religion and on into Second Temple Judaism. See more on widows in biblical texts at

In 1 Kings 17, the first two key incidents that we are told of regarding Elijah both involve this widow: the widow who offers hospitality to Elijah, and the widow whose son had died, but whom Elijah brought back to life. In the first scene, the tables are turned on the typical biblical view of widows, as vulnerable and in need of protection. Here,it is the widow who serves and nourishes the prophet at his time of need. In another evocation of what Jesus taught, we see the humble exalted, the man of power brought down to a position of dependence, perhaps?

Both scenes involving the widow of Zarephath, a non-Israelite, are evoked in the stories about Jesus: first, the generosity of the widow, offering hospitality out of her meagre provisions, is echoed in the positive words Jesus spoke about widows giving in the temple (Mark 12:41–44; and see also Luke 18:1–8).

Second, the raising of the widow’s son from the dead is paralleled in the story Luke tells about Jesus when he visited Nain (Luke 7:10–17). That story ends with the people declaring, “A great prophet has risen among us!” and “God has looked favorably on his people!” (Luke 7:16). The story of Elijah bringing the widow’s son back to life ends in similar fashion, as the woman confesses, “Now I know that you are a man of God, and that the word of the Lord in your mouth is truth” (1 Ki 17:24). The prophetic vocation of both Jesus and Elijah is confirmed by their performing such a deed. And that is precisely the point in mind as the narrator introduces the prophet Elijah to us in these two stories.