The Gospel reading for this coming Sunday contains some very well-known words of Jesus, which we remember as “the greatest commandment” (Mark 12:28–34). Here are ten things worth knowing about these words.

ONE. The greatest commandment identified by Jesus comes from Hebrew Scripture. When Jesus says that the greatest commandment is to “love the Lord your God”, he is repeating words from the start of a long section in Deuteronomy, which reports a speech by Moses allegedly given to the people of Israel (Deut 5:1–26:19). The speech retells many of the laws that are reported in Exodus and Leviticus, framing them in terms of the repeated phrases, “the statutes and ordinances for you to observe” (4:1,5,14; 5:1; 6:1; 12:1; 26:16–17), “the statutes and ordinances that the Lord your God has commanded you” (6:20; 7:11; 8:11).

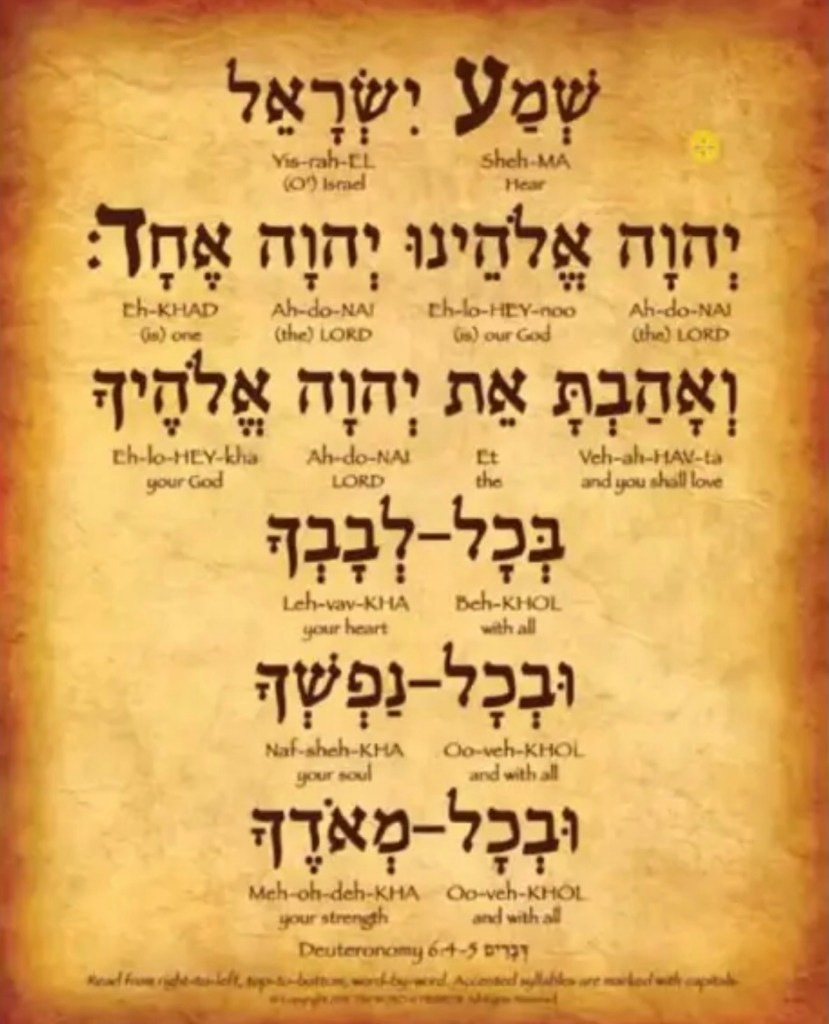

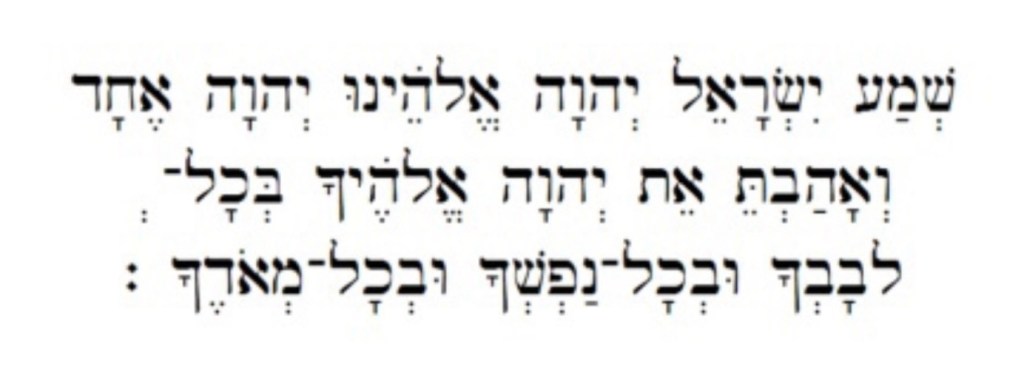

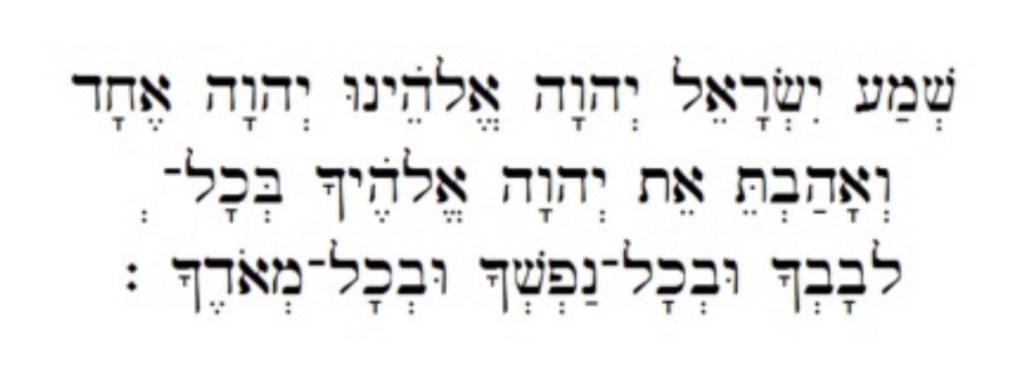

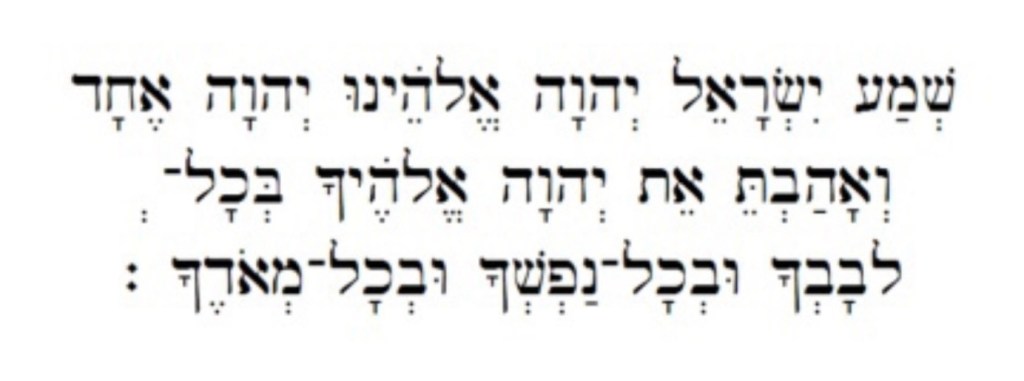

After proclaiming the Ten Commandments which God gave to Israel through Moses (Deut 5:1–21; cf. Exod 20:1–17) and rehearsing the scene on Mount Sinai and amongst the people below (5:22–33; cf. Exod 19:1–25; 20:18–21), Moses then delivers the word which provides the heading of all that follows: “Hear, O Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord alone. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might. Keep these words that I am commanding you today in your heart” (Deut 6:4–6). Love, it would seem, is the key commandment amongst all the statutes and ordinances found in this book.

These words are known in Jewish tradition as the Shema, a Hebrew word literally meaning “hear” or “listen”. It’s the first word in this key commandment; and more broadly than simply “hear” or “listen”, it carries a sense of “obey”. These words are important to Jews as the daily prayer, to be prayed twice a day—in keeping with the instruction to recite them “when you lie down and when you rise” (Deut 6:7). As these daily words, “love the Lord your God” with all of your being are said, they reinforce the centrality of God and the importance of commitment to God within the covenant people.

TWO. The original version of this commandment in Deuteronomy 6 has three parts: “with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might” (Deut 6:4). This is typical of Jewish speech; repetition, using different words which are related to the same concept, expressing the importance of what is being said; and especially, repetition in groups of three. So, the prophet Micah urges people to “do justice, love kindness, and walk humbly with God” ( Mic 6:8). Second Isaiah praises those messengers who proclaim peace, bring good news, and announce salvation (Isa 52:7).

The psalmist exhorts the people to “tell of his salvation … declare his glory … his marvelous works among all the peoples” (Ps 96:2-3). And the priestly authors of the creation story identifies all living creatures created by God in the threefold “fish of the sea … birds of the air … and every living thing that moves upon the earth” (Gen 1:28). That’s kind of like an ancient version of our “animal—mineral—vegetable” classification, I guess.

So the prayer of Deut 6:4 adheres to a widespread and longstanding literary feature in ancient Hebrew, of using three words in parallel. Just how parallel they are, we will now explore.

THREE. With all your heart: The Hebrew word translated as heart is לֵבָב, lebab. It’s a common word in Hebrew Scripture, and is understood to refer to the mind, will, or heart of a person—words which seek to describe the essence of the person. It is sometimes described as referring to “the inner person”. The word appears 248 times in the scriptures, of which well over half (185) are translated as “heart”.

Many of those occurrences are in verses which contrast heart with flesh—that is, “the inner person” alongside “the outer person”. For example, the psalmists declare that “my flesh and my heart may fail, but God is the strength of my heart and my portion forever” (Ps 73:26), and “my heart and my flesh sing for joy to the living God” (Ps 84:2b), whilst the prophet Ezekiel refers to “foreigners, uncircumcised in heart and flesh” (Ezek 44:7,9). When used together, these two terms (heart and flesh) thus often refer to the whole person, the complete being.

The Hebrew word lebab, heart, is rendered by the Greek word, kardia, in Mark 12:30. That word can refer directly to the organ which circulates blood through the body; but it also has a sense of the central part of a being—which is variously rendered as will, character, understanding, mind, and even soul. These English translations are attempting to grasp the fundamental and all-encompassing. It seems that this correlates well with the Hebrew word lebab, which indicates the seat of all emotions for the person.

FOUR. With all your soul: The second Hebrew word in the commandment articulated in Deut 6:4 is נֶפֶשׁ, nephesh. This is another common Hebrew word, appearing 688 times in Hebrew Scripture, of which the most common translation (238 times) is “soul”; the next most common translation is “life” (180 times). The word is thus a common descriptor for a human being, as a whole.

However, to use the English word “soul” to translate nephesh does it a disservice. We have become acclimatised to regarding the soul as but one part of the whole human being—that is the influence of dualistic Platonic thinking, where “body and soul” refer to the two complementary parts of a human being. In Hebrew, nephesh has a unified, whole-of-person reference, quite separate from the dualism that dominates a Greek way of thinking.

Nephesh appears a number of times in the first creation story in Hebrew scripture, where it refers to “living creatures” in the seas (Gen 1:20, 21), on the earth (Gen 1:24), and to “every beast of the earth, and to every bird of the air, and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life (nephesh hayah)” (Gen 1:30). It is found also in the second creation story, where it likewise describes how God formed a man from the dust of the earth and breathed the breath of life into him, and “the man became a living being (nephesh hayah)” (Gen 2:7). The claim that each living creature is a nephesh is reiterated in the Holiness Code (Lev 11:10, 46; 17:11).

The two words, nephesh and lebab, appear linked together many times. One psalmist exults, “my ‘heart’ is glad, and my ‘soul’ rejoices” (Ps 16:9a), whilst another psalmist laments, “how long must I bear pain in my ‘soul’, and have sorrow in my ‘heart’ all day long?” (Ps 13:2). Proverbs places these words in parallel in sayings such as “wisdom will come into your ‘heart’, and knowledge will be pleasant to your ‘soul’” (Prov 2:10), and “does not he who weighs the ‘heart’ perceive it? does not he who keeps watch over your ‘soul’ know it?” (Prov 24:12). In Deuteronomy itself, the combination of “heart and soul” appears a number of times (Deut 4:29; 10:12; 11:13, 18; 13:3; 26:16; 30:2, 6, 10), where it references the whole human being.

In each of these instances, rather than taking a dualistic Greek approach (seeing “heart” and “soul” as two separate components of a human being), we should adopt the integrated Hebraic understanding. Both “heart” and “soul” refer to the totality of a human being. The repetition is a typical Hebraic style, using two different words to refer to the same entity (the whole human being). The repetition underlines and emphasises the sense of totality of being.

FIVE. With all your might: The third Hebrew word to note in Deut 6:5 is מְאֹד, meod, which is usually translated as “might” or “strength”. Its basic sense in Hebrew is abundance or magnitude; it is often rendered as an adverb, as “very”, “greatly”, “exceedingly”, or as an adjective, “great”, “more”, “much”. The function of this word, “might” or “strength”, in Deut 6:5 is to reinforce the totality of being that is required to love God.

In light of this, we could, perhaps, paraphrase the command of Deuteronomy as love God with all that you are—heart and soul, completely and entirely. Love God with “your everythingness” (to coin a word). There’s a cumulative sense that builds as the commandment unfurls—love God with all your emotions, all your being, all of this, your entire being.

We find the same threefold pattern in the description of King Josiah, who reigned in the eighth century (640–609 BCE): “before him there was no king like him, who turned to the Lord with all his heart, with all his soul, and with all his might, according to all the law of Moses; nor did any like him arise after him” (2 Kings 23:25). Most often, however, it is used as an intensifier, attached directly to another term, providing what we today would do in our computer typing by underlining, italicising, and bolding a key word or phrase.

Rendering this Hebrew word in Greek—as the translators of the Septuagint did—means making a choice as to what Greek word best explicated the intensifying sense of the Hebrew word, meod. The LXX settled on the word δύναμις, usually translated as power (the word from which we get, in English, dynamic, and dynamite). Dynamis often has a sense of physical strength and capacity, and that resonates well with the sense of the Hebrew term as it is used in Deut 6:5. So the LXX has dynamis as the third element in the Shema commandment.

SIX. In the version we find at Mark 12, Jesus adds a fourth element: with all your mind. Where does this addition come from? Centuries before Jesus, an ancient scribe wrote an account of events in his society in a time long before his life. He reports the instruction that King David spoke to his chosen successor, his son, Solomon: “set your mind and heart to seek the Lord your God” (1 Chron 22:19). He reinforces that in a later address, telling Solomon to “know God and serve [the Lord] with single mind and willing heart” (1 Chron 28:9). The book of Proverbs (attributed by tradition to Solomon) then advocates both attending to the mind (Prov 22:17; 23:12, 19) and “inclining your heart” towards God (Prov 2:2; 3:1–6; 4:4, 20–23; 6:21; 7:3) as integral parts of the life of faith.

The injunction of David is echoed in the way that Jesus extends the traditional commandment to “love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might” (Deut 6:5), adding “and with all your mind” (Mark 12:30). There are scriptural resonances underpinning this addition made by Jesus.

SEVEN. The combined effect of these four phrases in the version of the command that Jesus speaks in Mark 12 is telling: Jesus instructs his followers that life with him requires a complete, total, fully-immersed commitment. He conveys this quite directly in other sayings: to a grieving person, “follow me, and let the dead bury their own dead” (Matt 8:22; Luke 9:60); to a farmer, “no one who puts a hand to the plow and looks back is fit for the kingdom of God” (Luke 9:62); and to a rich man, “go, sell what you own, and give the money to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; then come, follow me” (Mark 10:21 a d parallels).

Jesus also declares that “whoever loves father or mother more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever loves son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me; and whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me” (Matt 10:37–38; Luke 14:26–27), leading to his claim that those who have left “house or brothers or sisters or mother or father or children or fields, for my sake and for the sake of the good news” will indeed receive “eternal life in the age to come” (Mark 10:29–30). Discipleship is full-on!

EIGHT. Jesus then adds a second ”great commandment”, which also comes from Hebrew Scripture. As a good Jew, Jesus was well able to reach into his knowledge of Torah in his answer to the scribe who had asked him “which commandment is the first of all?”. The commandments that he selects have been chosen with a purpose. They contain the essence of the Torah: love God, love your neighbour. His answer draws forth the agreement of the scribe; in affirming Jesus, the scribe reflects the prophetic perspective, that keeping the covenant in daily life is more important that following the liturgical rituals of sacrifice in the Temple (see Amos 5:21–24; Micah 6:6–8; Isaiah 1:10–17).

The scene is similar to a Jewish tale that is reported in the Babylonian Talmud, a 6th century CE work. In Shabbat 31a, within a tractate on the sabbath, we read: “It happened that a certain non-Jew came before Shammai and said to him, ‘Make me a convert, on condition that you teach me the whole Torah while I stand on one foot.’ Thereupon he repulsed him with the builder’s cubit that was in his hand. When he went before Hillel, he said to him, ‘What is hateful to you, do not to your neighbour: that is the whole Torah, the rest is the commentary; go and learn it.’”

Hillel, of course, had provided the enquiring convert, not with one of the 613 commandments, but with one that summarised the intent of many of those commandments. We know it as the Golden Rule, and it appears in the Synoptic Gospels as a teaching of Jesus (Matt 7:12; Luke 6:31).

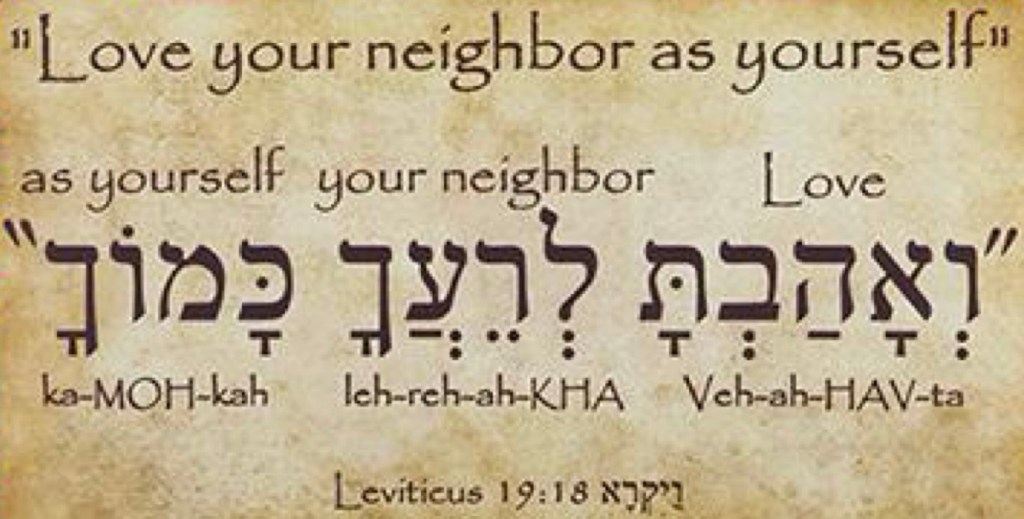

Some Jewish teachers claim that the full text of Lev 19:18 is actually an expression of this rule: “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbour as yourself: I am the Lord”. Later Jewish writings closer to the time of Jesus reflect the Golden Rule in its negative form: “do to no one what you yourself dislike” (Tobit 4:15), and “recognise that your neighbour feels as you do, and keep in mind your own dislikes” (Sirach 31:15).

NINE. Love of God is a thread running right through both testaments of scripture. The command is repeated in later chapters of Deuteronomy (10:12; 11:1; 13:3; 30:6) and in Joshua (22:5; 23:11). It is then picked up in all three Synoptic Gospels (Mark 12:30; Matt 22:37; Luke 10:27; 11:42) and echoed by Paul (Rom 8:28 and perhaps 2 Thess 3:5).

Finally, this claim is developed by the author of 1 John, who focusses on love as integral to the nature of God, declaring that “God is love” (1 John 4:16) and “love is from God” (4:7); and then explains that such love is expressed in the way that believers “love one another [for] if we love one another, God lives in us, and his love is perfected in us” (4:11–12), or that “the love of God is this, that we obey his commandments” (5:3); and that “those who do not love their brothers and sisters” are “not from God” (3:10; see also 4:19–20).

And so, the bold declarations are made that “whoever obeys [Christ’s] word, truly in this person the love of God has reached perfection” (2:5), and that “those who love God must love their brothers and sisters also” (4:21). In this way, the two commands to love are knitted together most completely.

TEN. Love of neighbour is also a consistent theme throughout scripture. After the command to “love your neighbor as yourself” (Lev 19:18), the Torah specifies that “the alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself” (19:34). Israelites are commanded not to defraud a neighbour (19:13), judge a neighbour “with justice” (19:15), not profit “by the blood of your neighbour” (19:16) and to deal justly with the neighbour in matters of commerce (25:14–15). The word of Moses in Deuteronomy is clear in the command to “open your hand to the poor and needy neighbour in your land” (Deut 15:11).

The book of Proverbs likewise counsels “do not plan harm against your neighbour who lives trustingly beside you” (Prov 3:29), “do not be a witness against your neighbor without cause, and do not deceive with your lips” (24:28), and warns that “like a war club, a sword, or a sharp arrow is one who bears false witness against a neighbour” (25:18). Its advice is, “better is a neighbour who is nearby than kindred who are far away” (27:10b).

Paul clearly knows the command to love one’s neighbour, for he quotes it to the Galatians: “the whole law is summed up in a single commandment, ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself’” (Gal 5:14), and to the Romans: “the commandments … are summed up in this word, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ Love does no wrong to a neighbor; therefore, love is the fulfilling of the law.” (Rom 13:9–10).

James also cites it: “you do well if you really fulfill the royal law according to the scripture, ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself’” (James 2:8). Both writers reflect the fact that this was an instruction that stuck in people’s minds! And I wonder … perhaps there’s a hint, in these two letters, that the greater of these two equally-important commandments is actually the instruction to “love your neighbour”?

So it is for very good reasons that Jesus extracts these two commandments from amongst the 613 commandments that are to be found within the pages of the Torah. (The rabbis counted them all up—there are 248 “positive commandments”, giving instructions to perform a particular act, and 365 “negative commandments”, requiring people to abstain from certain acts.)

Jesus, of course, was a Jew, instructed in the way of Torah. He knew his scriptures—he argued intensely with the teachers of the Law over a number of different issues. He frequented the synagogue, read from the scroll, prayed to God, and went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem and into the Temple—where, once again, he offered a critique of the practices that were taking place in the courtyard of the Temple (11:15–17).

Then he engaged in debate and disputation with scribes and priests (11:27), Pharisees and Herodians (12:13), and Sadducees (12:18). Each of those groups came to Jesus with a trick question, which they expected would trap Jesus (12:13). Jesus inevitably bests them with his responses (11:33; 12:12, 17, 27). It was at this point that the particular scribe in our passage approached Jesus, perhaps intending to set yet another trap for him (12:28). We have seen how masterful Jesus was, in engaging with—and besting in debate—this scribe in the way he responded to him. These two “greatest commandments” have endured for centuries!

See also