The lectionary Gospel reading for this Sunday (Mark 10:2–16) reports an encounter between Jesus and some Pharisees—the first such encounter in Judea, as earlier encounters had been in Galilee. I have already explored this story in the context of the cultural and religious context of the time, in late Second Temple Judaism.

In the debate that takes place in this encounter, Jesus quotes from the first creation story, the grand priestly narrative that occupies pride of place at the start of Bereshith, the first scroll of Torah, and thus at the beginning also of the scriptures collected by the followers of Jesus that formed what we know as The Holy Bible.

Words in origin stories have a particular power—and origin stories, such as this one (Gen 1:1–2:4a), are chosen with care and deliberation. That is certainly the case with this particular verse. In debating the Pharisees, Jesus says, “from the beginning of creation, ‘God made them male and female’” (Mark 10:6).

Here Jesus uses the verse as the claim that seals his particular stance regarding divorce—that it was not part of the plan that God had for humanity, since the male—female gender structure is integral to our humanity, and underscores his conclusion regarding divorce, that “what God has joined together, let no one separate“ (Mark 10:9). This, in turn, is his deduction from what the second creation story sets forth about marriage, that “a man leaves his father and his mother and clings to his wife, and they become one flesh” (Gen 2:24; quoted at Mark 10:7–8a). See

The statement by Jesus that God made human beings as male and female sounds like a definitive declaration: this is the reality, this is who we are, there is nothing more to debate! Certainly, that’s the way this verse has been used in the “gender wars” that have swirled through western societies in recent times. “God made male and female” became “God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve”, in an early salvo against the emerging number of people who were “outing” themselves as same-gender attracted. “Not so” was the sloganeers’ reply; two genders, each attracted to the opposite, is who we are. Definitively. Resolutely. Absolutely.

It’s worth going back to the quote from Genesis in its original context. What the priestly authors of the creation story wrote was “God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them” (Gen 1:27). The emphasis is not so much on defining who we are are gendered people—but rather, the verse is reflecting on the amazing feature that, within humanity, signs of divinity are reflected. And in association with that, the statement indicates that the two genders familiar from humanity are somehow reflected in the very nature of God.

As God’s creatures, we are images of that creating being. The Hebrew word used, tselem (image), indicates a striking, detailed correlation between the human and the deity. This was the insight brought by the authors of this passage, perhaps shaped and honed over generations of telling and retelling the story, passing on through the oral tradition the insights of older generations.

My sense is that these ancients were not so much making a definite declaration about the nature of humanity—an early dogmatic assertion, if you like—as they were actually reflecting on their experience. They sensed that there was something within humanity that reaches out, beyond the material, into the unknown, beyond the tangible, into “the spiritual”. They surely knew the kind of experience that Celtic mystics have known, of coming to a place where “heaven meets earth”—what they call “a thin place”, where God can be sensed in the ordinariness of life. Indeed, such a “thin place” might well be being described in Gen 28:10–22, where Jacob comes to the realisation that “surely, the Lord is in this place” (Gen 28:16).

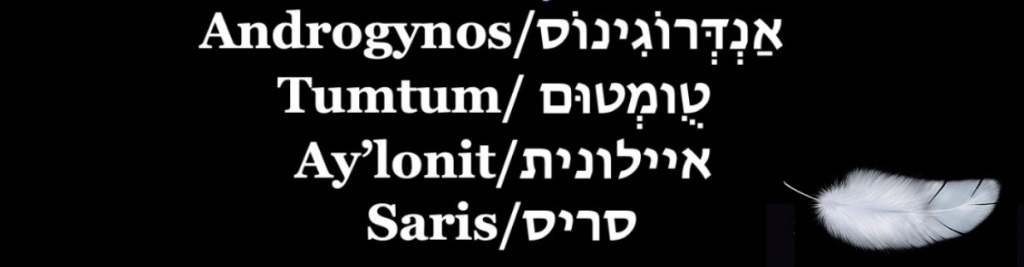

Indeed, as Jewish tradition developed over time, this fundamental duality of human gender—male and female—was questioned, probed, explored, and developed. Rabbis of late antiquity and the early medieval period (using the standard Western terminology) actually identified six genders. The first move takes place in the Mishnah (early 3rd century). Tractate Bikkurim 4.1 contains the assertion, “an Androginus (a hermaphrodite, who has both male and female reproductive organs) is similar to men in some ways and to women in other ways, in some ways to both and in some ways to neither”. It is interesting that the term androginus, a Greek term, is simply transliterated in this Aramaic work, as אדדוגינוס. That’s a sign that the consideration of this issue encompassed more than just rabbinic scholars, as they were drawing on insights and term androginus from the hellenised world.

of the Mishnah, entitled Zera’im (seeds).

The text of Bikkurim goes on to offer indications of the ways that an androginus person is similar to, and dissimilar to, each gender (4.2–3). Another passage in the Mishnah identifies people known as a saris, סריס (Yevamot 8.4). These are people we identify as eunuchs; whether these are “eunuchs who have been so from birth … eunuchs who have been made eunuchs by others … [or] eunuchs who have made themselves eunuchs” (as Matthew reports Jesus saying, Matt 19:12) is not relevant in this context; but we do meet such a person at Acts 8:27. Presumably, the rabbis refer to males with arrested sexual development who are unable to procreate. The female term for such people is given as aylonit, אילונית. The discussion that follows makes it clear that these people are women with arrested sexual development who cannot bear children.

So this means that rabbis recognised four genders: male, female, androgyne, and eunuch. In the Babylonian Talmud (sixth century CE), Rabbi Ammi is quoted as stating that “Abraham and Sarah were originally tumtumim” (טומטמין). Here we find another gender identity term; this time, describing people a person whose sex was unknown because their genitalia were hidden, undeveloped, or difficult to determine. (The Hebrew word tumtum means “hidden”.)

Thus, Abraham and Sarah lived most of their life as infertile, as their sex was not clear; and then, in Rabbi Ammi’s explanation, miraculously turned into a fertile husband and wife in their old age. The Rabbi points to Isa 51:1–2, saying that the instruction to “look to the rock from where you were hewn, and to the hole of the pit from where you were dug […] look to Abraham your father and to Sarah who bore you” explains their genitals being uncovered and miraculously remade.

(Explaining one scripture passage by drawing on another passage, however distantly related—often through their sharing a common word or phrase—was a common rabbinic mode of scripture interpretation.)

Today, we would explain the phenomenon of a tumtum as being an intersex person, born with both male and female characteristics, including genitalia—although modern science would not go so far as to accept a miraculous reversal of the condition, as Rabbi Ammi proposed.

There’s a quite accessible discussion of these issues in an article on My Jewish Learning by Dr Rachel Scheinerman, entitled “The Eight Genders in the Talmud”. The title reflects the fact that Dr Scheinerman divides both aylonit and saris into two, on the basis of birth identification. So she lists: (1) zachar, male; (2) nekevah, female; (3) androgynos, having both male and female characteristics; (4) tumtum, lacking sexual characteristics; (5) aylonit hamah, identified female at birth but later naturally developing male characteristics; (6) aylonit adam, identified female at birth but later developing male characteristics through human intervention; (7) saris hamah, identified male at birth but later naturally developing female characteristics; and (8) saris adam, identified male at birth and later developing female characteristics through human intervention.

Dr Scheinerman concludes, “In recent decades, queer Jews and allies have sought to reinterpret these eight genders of the Talmud as a way of reclaiming a positive space for nonbinary Jews in the tradition. The starting point is that while it is true that the Talmud understands gender to largely operate on a binary axis, the rabbis clearly understood that not everyone fits these categories.”

https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-eight-genders-in-the-talmud/

Dr. Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert, a Talmudic scholar in the Department of Religious Studies at Stanford University, California, has provided a much more detailed and technical discussion of the matter of gender identity, in the online resource the Jewish Women’s Archive. See

https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-eight-genders-in-the-talmud/

The abstract of this article reads:

“Jewish law is based on an assumption of gender duality, and fundamental mishnaic texts indicate that this halakhic duality is not conceived symmetrically (as seen through the gendered exemptions of some commandments). Rabbinic halakhic discourse institutes a functional gender duality, anchored in the need of reproduction of the Jewish collective body. As such, it aims to enforce and normalize a congruence between sexed bodies and gendered identities. Furthermore, the semiotics of body surfaces produces other different and seemingly more ambiguous gender possibilities, and rabbinic discourse has widely discussed the halakhic implications of these ambiguities.”

What that means, I think, is that whilst Torah prescriptions are based on a definite duality of gender (you re either male or female), later rabbinic discussions entertained the possibility of a range of gender identifications. In this regard, the rabbinic discussions prefigured the move in contemporary society to recognise the full spectrum of diversity amongst human beings: some men are gay, some women are lesbian; some people are bisexual, attracted to both genders, while others are asexual, having no sexual-attraction feelings at all.

Biologically, we know that some are born intersex, with both male and female physical characteristics; whilst psychologically, some people are born into a body that is clearly one gender have an internal energy that leads them to identify with the opposite gender, and so they undergo a medical transition to that gender, and we identify them as transgender people. And so, we have the now-widespread “alphabet soup” of LGBTIQA+ (where the plus sign indicates there may well be other permutations within this widely diverse spectrum).

So we would do well not to remain in a static state of assertion that the Genesis text is a prescription for how human beings should be identified (and a definition for marriage). I think it is preferable to add into the discussion both the rabbinic understandings, contemporary medical understandings, and psychological insights that reveal a wide spectrum of gender identities; a dazzling kaleidoscope of “letters”, as it were. For this is how we human beings are made, in an image that reflects the diversity and all-encompassing nature of God. Rather than misusing the Genesis/Mark text as a club to batter people into submission, let’s rejoice in the diversity we see amongst humanity, and affirm that, no matter whether L or G, whether B or A, whether T or I, all people who are Q, and all who are straight, are “fearfully and wonderfully made” (Ps 139:14).

There is a helpful collection of Jewish texts relating to this matter in the online resource, Sefaria, entitled “More Than Just Male and Female: The Six Genders in Ancient Jewish Thought”, collated by Rabbi Sarah Freidson of Temple Beth Shalom in Mahopac, NY, USA. See

https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/37225?lang=bi

See also