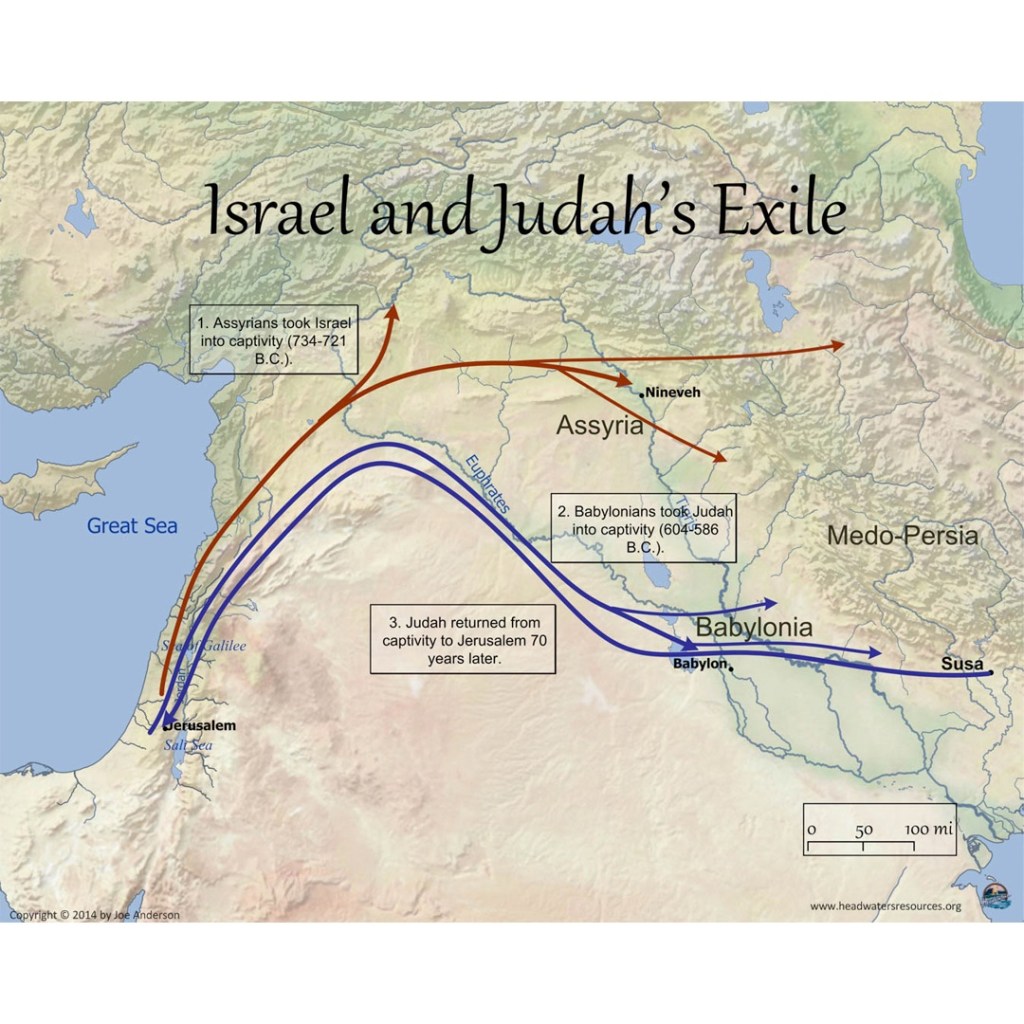

The prophet Jeremiah lived at a turning point in the history of Israel. The northern kingdom had been conquered by the Assyrians in 721 BCE; the elite classes were taken into exile, the land was repopulated with people from other nations (2 Kings 17). The southern kingdom had been invaded by the Assyrians in 701 BCE, but they were repelled (2 Kings 18:13–19:37). King Hezekiah made a pact with the Babylonians, but the prophet Isaiah warned that the nation would eventually fall to the Babylonians (2 Kings 20:12–19). Babylon conquered Assyria in 607 BCE and pressed hard to the south; the southern kingdom fell in 587 BCE (2 Kings 24–25) and “Judah went into exile out of its land” (2 Ki 25:21).

Jeremiah lived in the latter years of the southern kingdom, through into the time of exile—although personally, he was sent into exile in Egypt, even though most of his fellow Judahites were taken to Babylon. The difficult experiences of Jeremiah as a prophet colour many of his pronouncements. As the book moves on from the poetic oracles of chapters 1–25, to a series of prose narratives in chapters 26–45, some key events in the life of Jeremiah are reported.

The passage from Jeremiah proposed for this coming Sunday, the first Sunday in Advent (Jer 33:14–16), contains a specific prophecy which appears fitting for this season, as we anticipate the celebration of the birth of Jesus. It takes on a deeper meaning if we understand where it fits within the original historical context of the time when Jeremiah was speaking.

Jeremiah had been called as a youth to declare the message of the Lord to the people of Israel, that God was planning “to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant” (Jer 1:10). Years later, the adult prophet Jeremiah was called to “stand in the court of the Lord’s house and speak to all the cities of Judah that come to worship in the house of the Lord; speak to them all the words that I command you; do not hold back a word” (Jer 26:2). His message was about their failure to walk in the law that God had given them. The response from the ruling class is not positive—in fact, Jeremiah is threatened with death (26:7–11).

However, the midst of his despair, Jeremiah sees hope: “the days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will restore the fortunes of my people, Israel and Judah, says the Lord, and I will bring them back to the land that I gave to their ancestors and they shall take possession of it” (30:3). In this context, Jeremiah indicates that the Lord “will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah … I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (31:31–34).

To signal his confidence in this promised return, Jeremiah buys a field in his hometown of Anathoth from his cousin Hanamel (32:1–15). The narrator notes that “the army of the king of Babylon was besieging Jerusalem, and the prophet Jeremiah was confined in the court of the guard that was in the palace of the king of Judah, where King Zedekiah of Judah had confined him” (32:2–3). Nevertheless, the purchase serves to provide assurance that the exiled people will indeed return to the land of Israel; “houses and fields and vineyards shall again be bought in this land” (32:15).

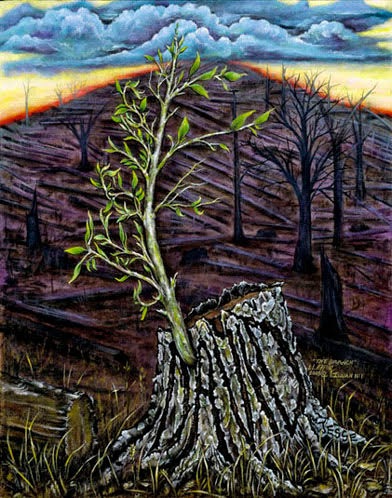

Jeremiah exhorts the people to “give thanks to the Lord of hosts, for the Lord is good, for his steadfast love endures forever!” (33:11), because in the places laid waste by the Babylonians, “in all its towns there shall again be pasture for shepherds resting their flocks … flocks shall again pass under the hands of the one who counts them, says the Lord” (33:12–13). As the people return to the land, the Lord “will cause a righteous Branch to spring up for David; and he shall execute justice and righteousness in the land” (33:15). The title “Son of David” is later applied to Jesus in three Gospels (Mark 10:47–48; Matt 1:1; 12:23; 15:22; 21:9, 15; Luke 18:38–39).

The prophet Isaiah also refers to the “shoot [which] shall come out from the stump of Jesse, and a branch shall grow out of his roots; the spirit of the Lord shall rest on him” (11:1–2). The appearance of this “shoot” will lead to the promised time when “the wolf shall live with the lamb, the leopard shall lie down with the kid, the calf and the lion and the fatling together, and a little child shall lead them” (11:6)—a wonderful Messianic prophecy.

Jeremiah, in an earlier oracle, had declared that “the days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, and he shall reign as king and deal wisely, and shall execute justice and righteousness in the land” (Jer 23:5). His words at Jer 33:14–16 repeat this message of hope. That hope, in Christian theology, was taken up in Jesus, who was claimed to be the righteous branch, the one ruling with justice (Matt 12:15–21). Jesus spoke clearly about the need for justice in our lives (Matt 23:23; Luke 7:29). He spoke in the tradition of the prophets, including Jeremiah, who had regularly reminded the people,of Israel of the centrality of doing justice for those who were obedient to the covenant with the Lord God.

In speaking out for justice, Jesus provided a clear countercultural vision for his followers, and called them into a radically different way of living. It is that Jesus whom we celebrate at Christmas, and that countercultural vision that is at the heart of the Advent season.