Today (in the Western Church) is designated as the Feast of the Holy Innocents. (It is celebrated tomorrow in the Eastern Church.) This festival day commemorates a tradition known as “the slaughter of the Innocents”, reportedly ordered by King Herod. It’s a gruesome attachment to the story that is told in the Gospel of Matthew that begins, “now the birth of Jesus the Messiah took place in this way” (Matt 1:18).

The tradition is that when Herod learnt of the birth of “the King of the Jews”, he feared that this king would pose a threat to his own rule (as a client king under the Roman Empire) over the Jewish people. Herod, it is said, ordered that all male children under two years of age should be killed, to ensure that this rival king was safely despatched (Matt 2:16). Jesus survived this because after visitors “from the east” came from the court of Herod to pay tribute to him (2:11), his parents were advised of the imminent pogrom by an angelic visitation (2:13).

by Léon Cogniet, held in the Musée des Beaux-Arts

The story is told only in Matthew’s Gospel. It is highly unlikely that the events reported by Matthew actually took place. First, his is the only account of such an event in any piece of literature from that time. An event with so many deaths would surely have been noted by other writers. It is true that Herod was a tyrannical ruler; but amongst the various accounts of his murderous deeds, there is nothing which correlates to the events reported in Matthew’s Gospel.

Second, the story is embedded in the opening section of the Gospel, which uses typical Jewish typology and scripture-fulfilment to present the story of Jesus as a re-enactment of the story of Moses. The author of Matthew’s Gospel, a follower of Jesus who had been raised as a faithful Jew, was especially partial in the opening chapters of his work to quoting scripture and claiming that events that he reports “took place to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophet” (1:22–23).

The chief priests and scribes in the royal court, says this author, told Herod that Jesus had been born in Bethlehem, “for so it has been written by the prophet” (2:4–6); the flight into Egypt of Joseph, Mary, and their newborn child was “to fulfill what had been spoken by the Lord through the prophets (2:15); the slaughter of the children itself “fulfilled what had been spoken through the prophet Jeremiah” (2:17–18); and the return of the family some time later and their settling in Nazareth was “so that what had been spoken through the prophets might be fulfilled” (2:21–23).

Aiding and abetting these notes of scripture fulfilment are other typical elements in the Jewish traditions of storytelling, namely, that the events as they take place are guided by the appearance of an angel in the dreams of Joseph (1:20–21; 2:13; 2:19) as well as direct guidance mediated by a dream of the visitors “from the east” (2:12) and again in a further dream of Joseph (2:22). The story that appears in Matt 1:18–2:23 would readily have been recognised by Jewish listeners as employing the typical elements and patterns of Jewish haggadic midrash.

See https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/midrash-and-aggadah-terminology

The book of Exodus also employed these elements and patterns. It opens in the time when “a new king arose over Egypt, who did not know Joseph” (Exod 1:8). This king, unnamed except for the designation of “Pharaoh”, feared the increasing numbers and growing power of the Israelites who been enslaved in Egypt for hundreds of years, determined that he would slow the rate of increase and lessen the power of the Israelites by decreeing, “every boy that is born to the Hebrews you shall throw into the Nile, but you shall let every girl live” (Exod 1:22).

It is in this context that Moses is born; he is hidden “among the reeds on the bank of the river” (Exod 2:1–4), and then taken home by the daughter of Pharaoh (Exod 2:5–9), adopted by her, and raised as a member of the royal household (Exod 2:10). The origin of the child is revealed to the readers (but presumably not to the Pharaoh) by his being named Moses, because, as Pharaoh’s daughter said, “I drew him out of the water” (Exod 2:10b).

The fact that a name conveys a deeper meaning has been found again and again in the traditional tales collated to form the narrative of Genesis: Adam reflects his creation “from the dust of the ground” (Gen 2:7), Eve’s name indicates that she is “the mother of all living” (3:20), Cain means “acquired” and is reflected in Eve’s comment that “I have produced [or acquired, qanah] a man with the help of the Lord” (4:1), and Abel is related to the Hebrew word for “emptiness” (havel).

Abram’s name is changed to Abraham, which means “leader [ab] of multitudes [raham]”, to signal the covenantal promise of the Lord God that “I will make you exceedingly fruitful; and I will make nations of you, and kings shall come from you … for an everlasting covenant, to be God to you and to your offspring after you” (17:4–6). The name of the aged, barren Sarai is changed to Sarah, meaning “she laughed” (17:15), to signal her incredulous response to the news that she will bear a child (18:9–15). The name of Ishmael literally means “God listens” (16:11) and that of Jacob means “he who supplants” (25:24–26); after his all-night struggle with a man at the ford of Jabbok (32:22–24), his name was changed to Israel, meaning “the one who strives with God” (32:28). Names are deeply significant!

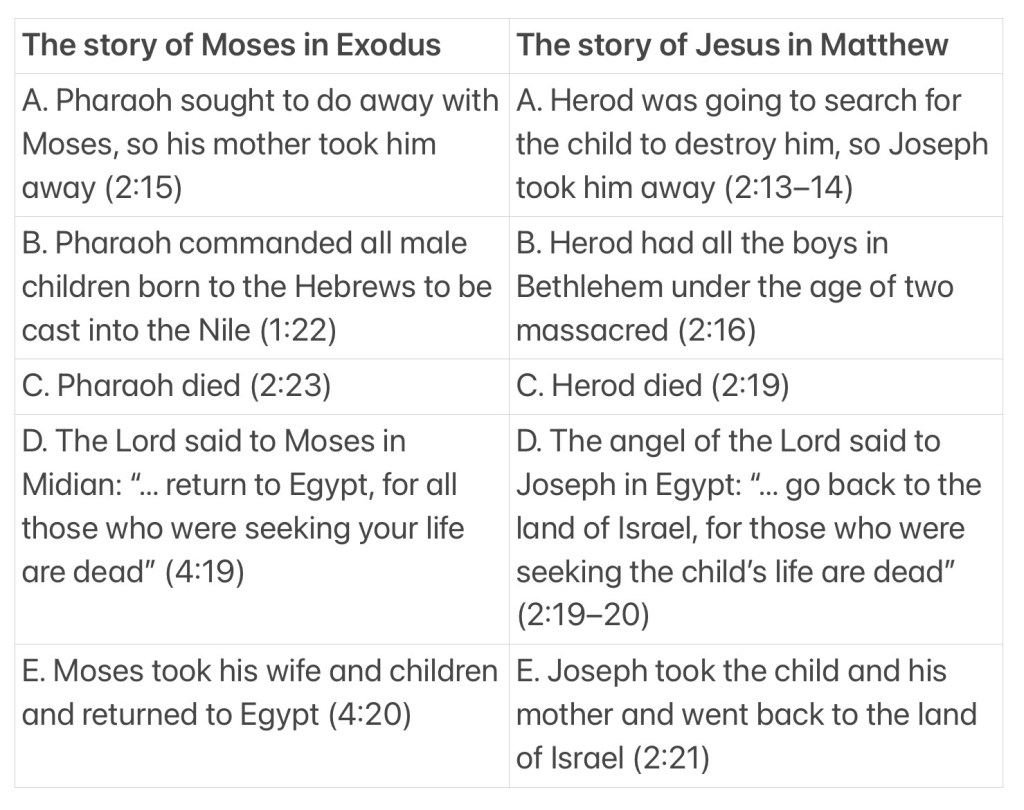

So Moses means “drawn from water”, and Jospeh is given the message that his son is to be given the name that signifies his role, Jesus: “for he will save his people from their sins” (Matt 1:21). And the ancient tale of the slaughter of infants at the time of the birth of Moses is replicated at many points in Matthew’s account of the slaughter of infants at the time of the birth of Jesus (Matt 2:1–18). This later account simply fits the pattern of the earlier account, as this chart shows:

The parallels are very clear!

And just as the literary structure of each story runs in the same pattern, so also the “historical” similarities are clear. Just as there is no historical evidence beyond Exodus to corroborate that the story of the pogrom at the time of Moses took place, neither is there evidence beyond the Gospel of Matthew to corroborate the account found there. Both patterns of events were stories, tales told, not history recorded.

But these non-historical stories are important for theological reasons. The Moses story is part of the whole Exodus complex that provides the fundamental explanation for the identity of Israel. The Jesus story as Matthew presents it is part of the foundational myth of the Christian faith. The writer of Matthew’s Gospel wants to make strong correlations between Jesus and Moses, as the two key figures in their respective stories—and religious systems. This starts in the mythological account found in the opening chapters, and continues throughout the following chapters of the Gospel.

As myth, the tradition found in Matt 1—2 points to important truths. The Slaughter of the Innocents grounds the story of Jesus in the historical, political, and cultural life of the day. It provides a dreadful realism to a story which, all too often in the developing Christian Tradition, has become etherealised, spiritualised, and romanticised.

So we remember this story as an important pointer to the counter-cultural, alternative-narrative impact of the person of Jesus. It is not history, but it offers a powerful myth.

A traditional hymn which remembers this tradition is the Coventry Carol. This dates from the 16th century, when it was performed in Coventry, England, as a part of a mystery play entitled The Pageant of the Shearman and Tailors.

The single surviving text of this pageant (including the words of this carol) was published by one Robert Croo, who dated his manuscript 14 March 1534. The carol is in the form of a lullaby, sung as a poignant remembrance by the mother of a child who is doomed to die in the pogrom.

Lully, lullay, thou little tiny child,

Bye bye, lully, lullay.

Lully, lullay, thou little tiny child,

Bye bye, lully, lullay.

O sisters too, how may we do

For to preserve this day

This poor youngling for whom we sing,

“Bye bye, lully, lullay”?

Herod the king, in his raging,

Charged he hath this day

His men of might in his own sight

All young children to slay.

That woe is me, poor child, for thee

And ever mourn and may

For thy parting neither say nor sing,

“Bye bye, lully, lullay.”