The lectionary invites us this week to hear the final section of 1 Cor 15, which has offered a lengthy consideration of the “resurrection of the dead ones” (a raising of many believers) and the “resurrection of Jesus”. Resurrection was a Jewish belief that had developed in preceding centuries; not all Jews accepted it (see Acts 23:6–8) and amongst some Gentiles there was scepticism about the idea (see Acts 17:32).

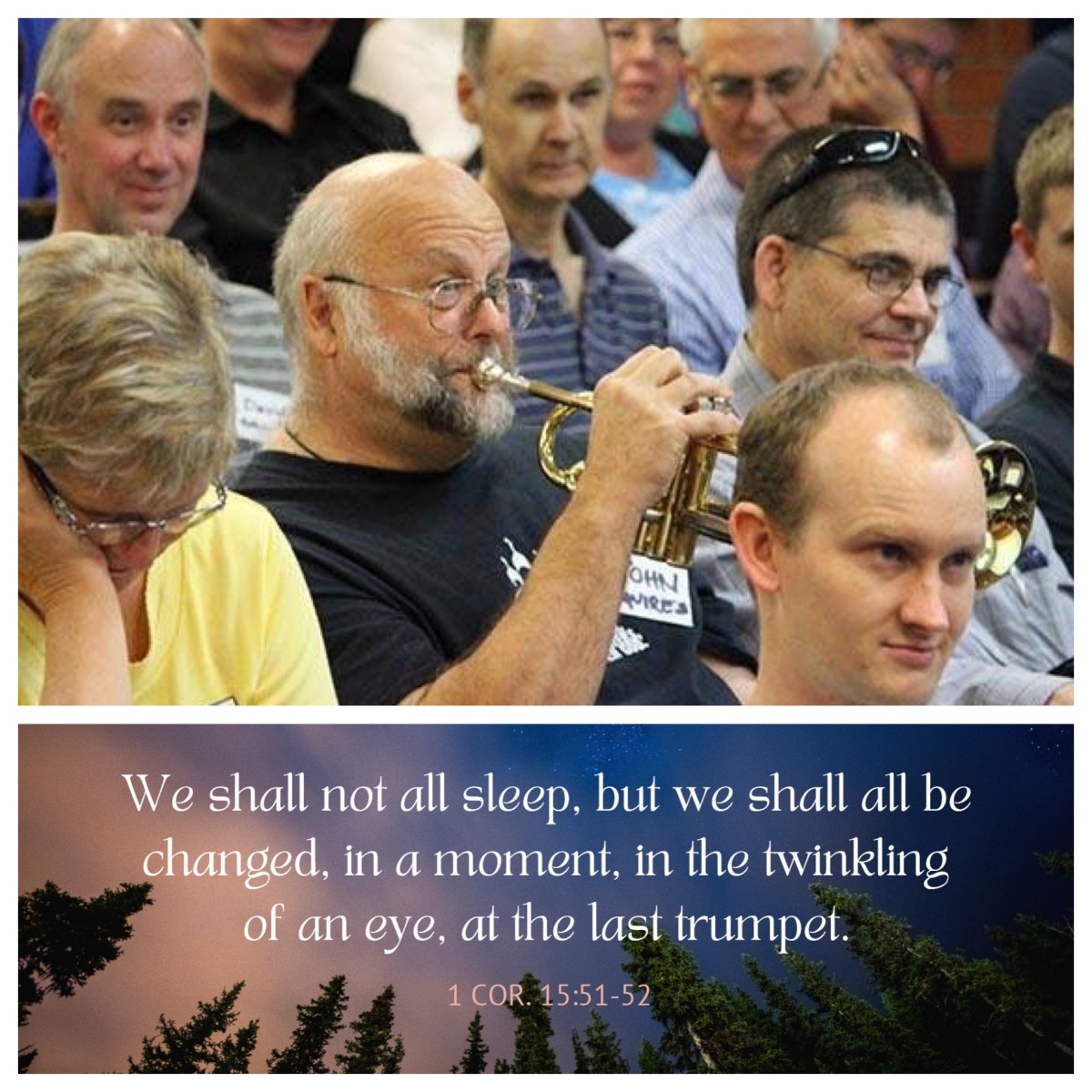

There was also dispute about this matter in Corinth, resulting in a number of debates about particular aspects of this belief. In the verses of 1 Cor 15 dealt with in recent weeks, a number of matters have been explored, debated in fine rhetorical style, and dispatched. To conclude their reflections on this matter (15:50–58), Paul and Sosthenes offer a final glimpse into the eschatological drama that awaits at “the end of time”. “What [we] are saying”, they declare, “is this: we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet” (15:51–52).

The argument now is no longer logic-based, as they move through a sequence of vividly-imagined images in a dramatic rhetorical style. The whole long discussion of this matter ends with a simple, concise ethical exhortation: “be steadfast, immovable” (15:58). The eschatological language used in getting to this point, in these last few verses, is poetic, not realistic; it is evocatively-inspiring, not argumentatively-logical. The argument is brought to a conclusion with a sequence of images, not with any list of legal definitions.

What do we make of the concept of resurrection? Earlier in this chapter, the letter writers have asserted quite forcefully that “if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sin” (15:17). Are we therefore not at liberty to interrogate this concept, of the resurrection of Jesus and thus the resurrection of the dead, beyond affirming that it is essential to the faith? My mind recoils at such a stricture! I am committed, as this blog’s name indicates, to “an informed faith”, a faith in which the exercise of “all your mind” is integral to its full understanding and full expression.

So what, then, do we make of resurrection? Contemporary debate has canvassed a number of options as to the nature of the resurrection: Must it be in a bodily form? Was Jesus raised “in the memory of his followers”, but not as a physical body? Is resurrection a pointer to a transcendent spiritual dimension? What was meant by the reference to an “immortal state” in 1 Cor 15:53-54?

Some believers aggressively promote the claim that we must believe in the boldly resurrection of Jesus, that we must adhere to a literal understanding of what the biblical texts report. I prefer to advocate for ways of responding to the story which are creative, imaginative, expanding our understandings and drawing us away from age-old doctrinal assertions which are grounded in obsolete worldviews, on into new explorations of how this metaphor can make sense for us in our lives in the 21st century.

My basic position (as I hinted at towards the end of my previous blog on 1 Cor 15) is that resurrection is a claim that does not direct us away from this world, into a heavenly or spiritual realm. The resurrection offers us both an invitation to affirm our bodily existence in this world, and to explore fresh ways of renewal and recreation in our lives, in our society. It is about liberating life for renewal in our own time and place, here in this world.

It is the apostle Paul who, most of all in the New Testament, provides evidence for the way that early believers began to think about the central aspects of the Easter story—death on the cross, newness in the risen life (Rom 6:3-4:23, 8:6,13; 1 Cor 15:21-23; 2 Cor 4:8-12; Phil 2:5-11, 3:10-11). Paul probably did not begin such ideas; indeed, in both arenas, there are clear Jewish precedents. These were ideas that were live at the time.

However, the application of these ideas to Jesus—and their insertion into the story of his life—has moved them into a different dimension. They seem, to some, to be “historical events”. I think this pushes things too far. Certainly, Jesus died; but the evaluation of his death as a sacrifice is an interpretive move. In same fashion, the story of Jesus being raised from death was an interpretive move made within a context where “resurrection” was a live idea. In our context, it is a contested idea which sits uneasily within our scientific understandings.

I maintain that other writers in the New Testament provide important keys for understanding the function that “resurrection” plays in our faith. In Luke’s Gospel, the notion that Jesus may be appearing to the disciples as “a ghost” (the Greek is pneuma, usually translated as “spirit”) is dismissed when Jesus instructs the disciples to “look at my hands and my feet; see that it is I myself; touch me and see; for a ghost (pneuma) does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have” (Luke 24:38–39). Here, the emphasis is on the fact that the risen Jesus bears the marks of the crucified Jesus; in his resurrected form, the scars and burdens of his human life continue to be manifest.

In like fashion, when John recounts what may well be his version of the same scene, he puts to the fore the claim by the initially-absent Thomas that Jesus will only be identifiable by “the mark of the nails in his hands” and the wound on his side (John 20:25). So, a week later, when Jesus appears again, he instructs Thomas to “put your finger here and see my hands; reach out your hand and put it in my side” (John 20:27). It is on this basis—the tangible evidence of the crucifixion markings on the body of the resurrected Jesus—that Thomas can move from doubt to belief.

So, in these stories, the primary function of the appearance of the risen Jesus is not to point away from life on earth to some imagined heavenly realm—rather, it is to point back immediately to the scars of the cross, carried for eternity in the resurrected body of Jesus. It is an evocative, poetic presentation.

I return to 1 Cor 15, and the claim that the language used here is also poetic, proceeding in a series of images. Paul and Sosthenes do not conclude their rhetorical dissertation on resurrection with logic-based argumentation, but with a poetic doxology. What concludes the detailed argument of this long chapter is a simple outburst of thanksgiving: “thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ” (15:57).

Indeed, such doxologies characterise a number of the letters of Paul. In Romans, they punctuate the complex theological argumentation of this longest letter at key moments. “Thanks be to God”, he rejoices at the end of the tortured discussion of Law, sin, and death (Rom 7:25a). “I am convinced that … nothing in all creation will be able to separate us from the love of God in Jesus Christ our Lord”, a chapter later (8:38–39). Then, after three complex midrashic chapters about Israel, the exultant “O the depths of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God … to him be the glory forever; Amen” (11:33–36).

Finally, in drawing to a close, Paul offers the Romans a prayer of hope (15:13), a brief blessing (15:33), and a reiteration of the offering of grace (16:20b). In a final redaction of the letter, a later scribe then added a most flowery doxology as the conclusion to the whole letter (16:25–27).

The phrase used at 1 Cor 15:57, “thanks be to God”, appears also in Romans (6:17; 7:25) and 2 Corinthians (2:14; 8:16; 9:15); and see also 1 Thess 1:2; 2:13. Paul peppers his letters with notes of praise and adoration addressed towards God. This is poetry that evokes emotions—not words that wrangle doctrines. Such is the nature of his final word on resurrection at 1 Cor 15:57.

The brief word that follows this doxology is a word of hope-filled assurance to the Corinthians, whom he has criticised so mercilessly at many places throughout the letter: “you know that in the Lord your labour is not in vain” (15:58). The letter writers have earlier reminded the saints in Corinth what they know in a string of affirmations, most introduced with the rhetorical “do you not know?”. These affirmations include “you are God’s temple and God’s Spirit dwells in you” (3:16; similarly, 6:19), “a little yeast leavens the whole batch of dough” (5:6), “the saints will judge the world” (6:2), “wrongdoers will not inherit the kingdom of God” (6:9), “your bodies are members of Christ” (6:15), and “‘no idol in the world really exists’ and “there is no God but one” (8:4).

In the discussion of the rights of an apostle, they are reminded that “those who are employed in the temple service get their food from the temple, and those who serve at the altar share in what is sacrificed on the altar” (9:13) and “in a race the runners all compete, but only one receives the prize” (9:24). In the introduction to the discussion of “the body”, they are reminded that “when you were pagans, you were enticed and led astray to idols that could not speak” (12:2), and I the extended discussion of the use of gifts in worship, there are regular reminders about their knowledge (14:7, 9, 11, 16; and most controversially, v.35).

Here the reminder of what the saints “know” is the encouraging word, “in the Lord your labour is not in vain” (15:58). It is a typical teaching technique, drawn directly from the heart of the traditions of paraenesis (exhortation, or encouragement) which characterizes all of the letters of Paul. So the chapter ends both with praise directed to God and (despite their conflicts and scepticism) encouragement offered to the Corinthians. It is an uplifting conclusion.

See also