Two weeks ago we heard Luke’s account of the speech that Peter gave to the church, gathered in Jerusalem, about the moment when the Spirit fell upon the Gentile household of Cornelius and the conclusion that he drew, that “God has given even to the Gentiles the repentance that leads to life” (Acts 11:1–18).

Then, last Sunday, we heard a portion of Luke’s narrative from later in the book, which takes place soon after Paul and Barnabas had travelled to Jerusalem to report to a later gathering about their activity about “all the signs and wonders that God had done through them among the Gentiles” (Acts 15:1–21).

This Sunday’s passage (16:9–15) begins in Troas. Paul, Silas, and Timothy had travelled through Asia Minor (16:1–5), bringing to the assemblies they visit the decree of the Jerusalem council (16:4). As they went through the region of Phrygia and Galatia, they hear an instruction not to speak in the southern region of Asia from the holy spirit (16:6). Then they are forbidden by “the spirit of Jesus” to head north and enter Bithynia (16:7), so they go to Troas, where a vision is seen in the night with a petition to “come across into Macedonia” (16:9).

Luke is keen for those who read his work and hear it read to understand that Paul, Silas, and Timothy are guided by the spirit, seeing visions sent by God. These are common occurrences in Acts. The move into Macedonia is supported with the succinct statement that “God has called us to preach the good news to them” (16:10). It is completely consistent with “the plan and purpose of God” that the apostles have consistently been declaring (see 2:23; 4:28; 5:29, 38–39; 10:42). See

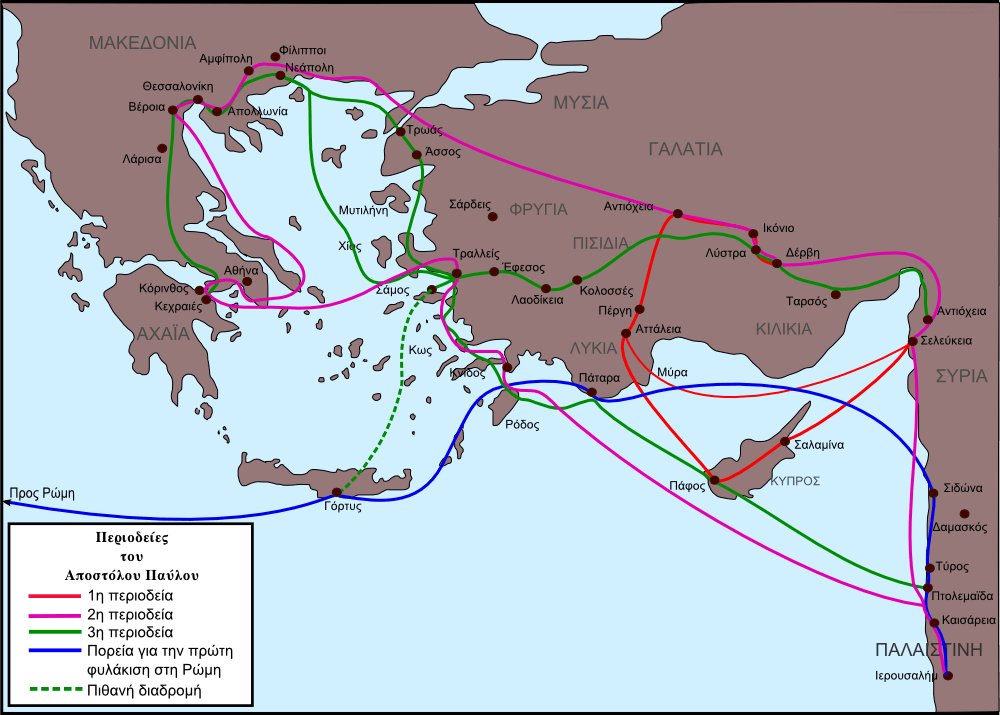

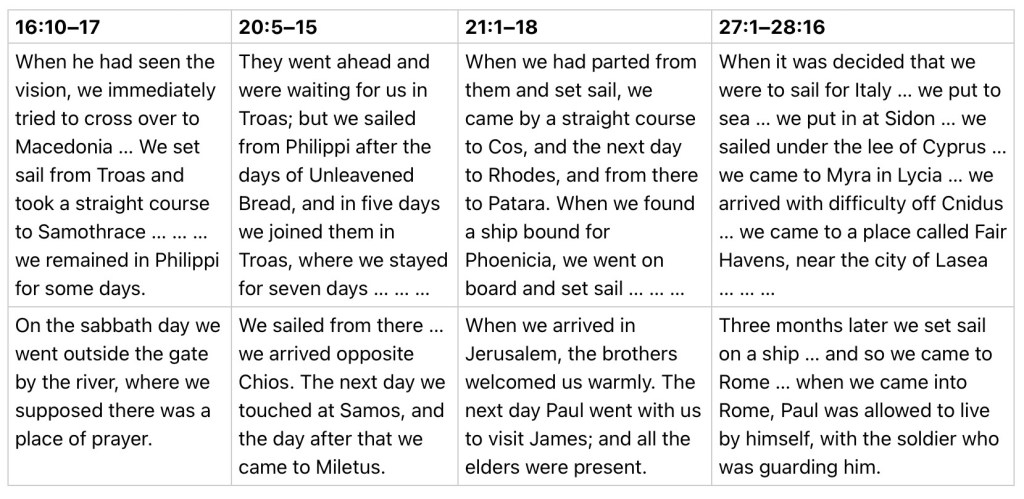

This statement (16:10) begins the first of the so-called ‘we-sections’ of Acts, which are narrated in the first person plural. Three of these are but brief notes concerning journeys (from Troas to Philippi, 16:10–17; from Troas to Miletus, 20:5–15; from Miletus to Jerusalem, 21:1–18). Each of these passages contain lists of the places visited and the means of travel (16:11–12; 20:5–6,13–15; 21:1–3,7–8,15) and small vignettes concerning one incident that took place on the journey (16:13–15; 20:7-12; 21:4–6, 10– 14).

The fourth ‘we-section’ encompasses the extensive series of journeys by which Paul travels from Caesarea to Rome (27:1-28:16). It includes mention of places and means of travel, as well as a number of particular incidents.

Scholarly opinion over the historical value of the ‘we sections’ is divided. Some have argued that there is evidence for an ancient literary convention, by which an author can alternate third person (“he”, “they”) and first person (“I”, “we”) narratives. In this view, Luke makes use of the first person narrative to strengthen the sense of unity felt between author and audience, and the characters in the events narrated.

However, others have criticised this claim and argued that the use of “we” indicates that these passages, at least, must go back to an eyewitness. The likelihood of ever being able to prove that the author of Acts was himself present with Paul in these journeys is low; at best, we might conclude that Luke had available to him a very brief source which may possibly have had its origins amongst Paul’s fellow travellers. (See also 20:5).

As the group crosses over into Macedonia, an ancient province of Greece which had been the dominant political power four centuries earlier, they arrive in Philippi (16:11–40), a city founded by Philip of Macedonia in 356 BCE, taken under Roman rule in 167 BCE, and declared a Roman colony (as Luke accurately notes, 16:12) in 31 BCE.

The group proceeds, in typical fashion, to find a place of worship on the sabbath (16:13)—not, as expected, a synagogue (see 13:5), but “a place of prayer” (16:13) for some women. (That the place of prayer was, in fact, a synagogue, is argued by a number of scholars. One scholar, Matson, describes the house church in Philippi as “a subversive contrast society”.)

One of this number, Lydia, is singled out for attention. Lydia is a godfearer (16:14), as was Cornelius (10:2) and probably the Ethiopian (8:27); what will occur here will place Lydia in a paradigmatic position akin to that occupied by Cornelius. Lydia is the first individual convert identified once Paul, Silas and Timothy, under divine guidance, have crossed over into Macedonia (16:6–10).

So Lydia presents a paradigm for the process of conversion and leadership; as the first convert in Europe, she models a faithful response to the message of Paul. Indeed, what takes place in this scene is directly interpreted as an act of God, for “the Lord opened her heart” (16:14) to listen eagerly to Paul’s words. The “opening of her heart” (16:14) echoes the discoveries made by the archetypal disciples on the walk to Emmaus (Luke 24:31,32) and by the larger group of followers gathered in Jerusalem later that day (24:45). Her “eager listening” (16:14) repeats the response evoked by Philip in Samaria (8:6).

Lydia is judged as being “faithful to the Lord” and, with her household, is baptised (16:15), in accord with the programmatic declaration of Peter’s Pentecost exhortation (2:38–39). The baptism of her household follows the pattern already seen in Caesarea (10:24–48; 11:13–16) and foreshadows a pattern which will be repeated soon in Philippi (16:31-33), and subsequently in Corinth (18:8).

Her belief leads to the offer of hospitality (16:15), as was also the case with the Gentiles in Caesarea (10:48); this same pattern follows in the story of the conversion of the Philippian gaoler and his household (16:34). Belief, baptism and table fellowship have also been linked in the accounts of the conversion of Saul (9:18-19), Cornelius and his household (10:24-48) and the events on Pentecost in Jerusalem (2:41-47). Lydia’s role as a patroness echoes that of Mary, the mother of John Mark, in Jerusalem (12:12) and prefigures that of Priscilla (with Aquila, 18:13). She is a striking figure in the overall narrative of Acts.

*****

Some of this material is from my commentary on “The Acts of the Apostles” in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible (ed. J.D.G. Dunn and John Rogerson; Eerdmans, 2003). I have also explored the theme of the plan of God at greater depth in my doctoral research, which was published in 1993 by Cambridge University Press as The plan of God in Luke-Acts (SNTSM 76).

On Lydia, see also