Continuing the story of the half-acre block in the centre of the town which Elizabeth and I bought five years ago; the block which has the house that we are now living in.

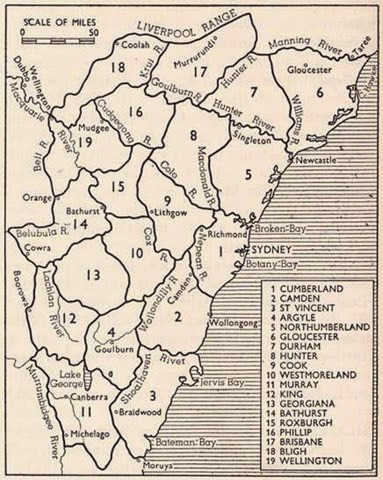

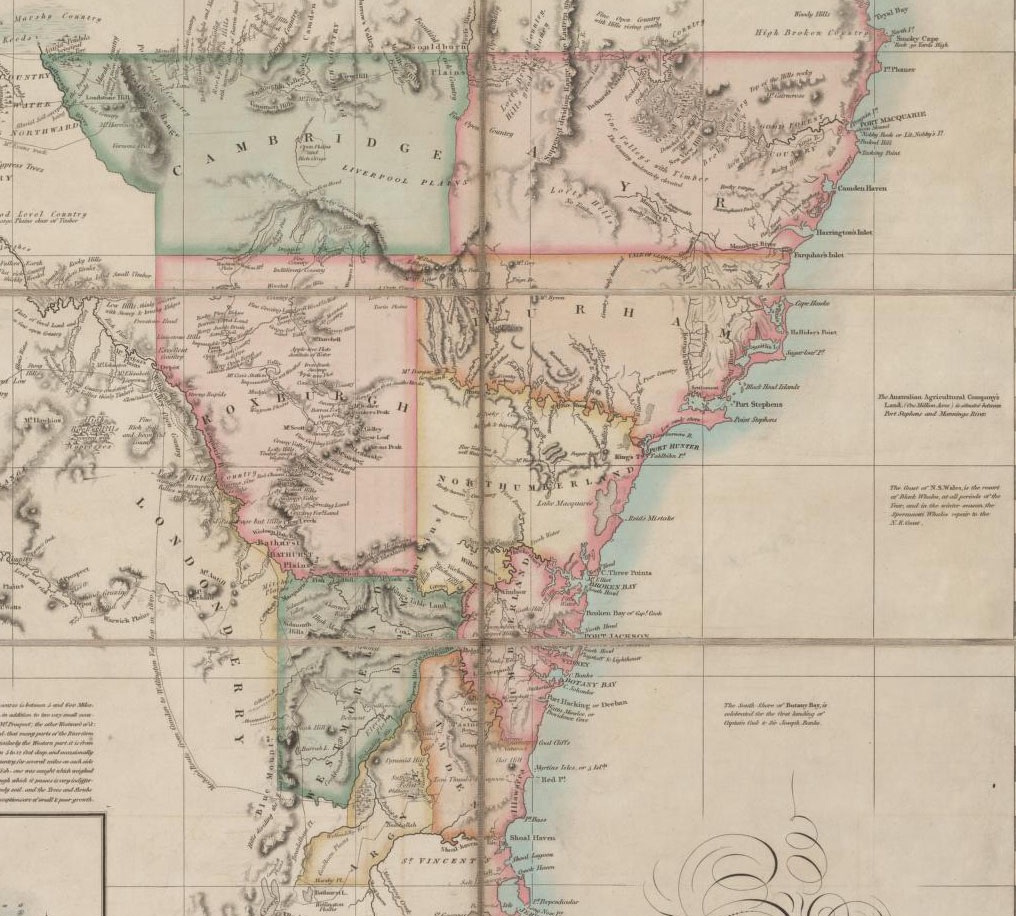

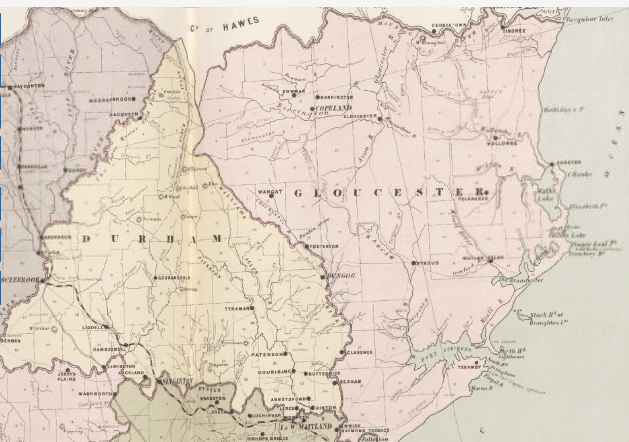

It turns out that we are just the latest in a line of people who have owned this particular block since soon after it was put up for sale, under the land ownership system of the invading British colonisers, in 1842. We know that this land had been Gringai land for millennia prior to the arrival of the British. We know also that they systematically and relentlessly marginalised the First Peoples and laid claim to the land, both locally, and indeed right across the continent we now know as Australia.

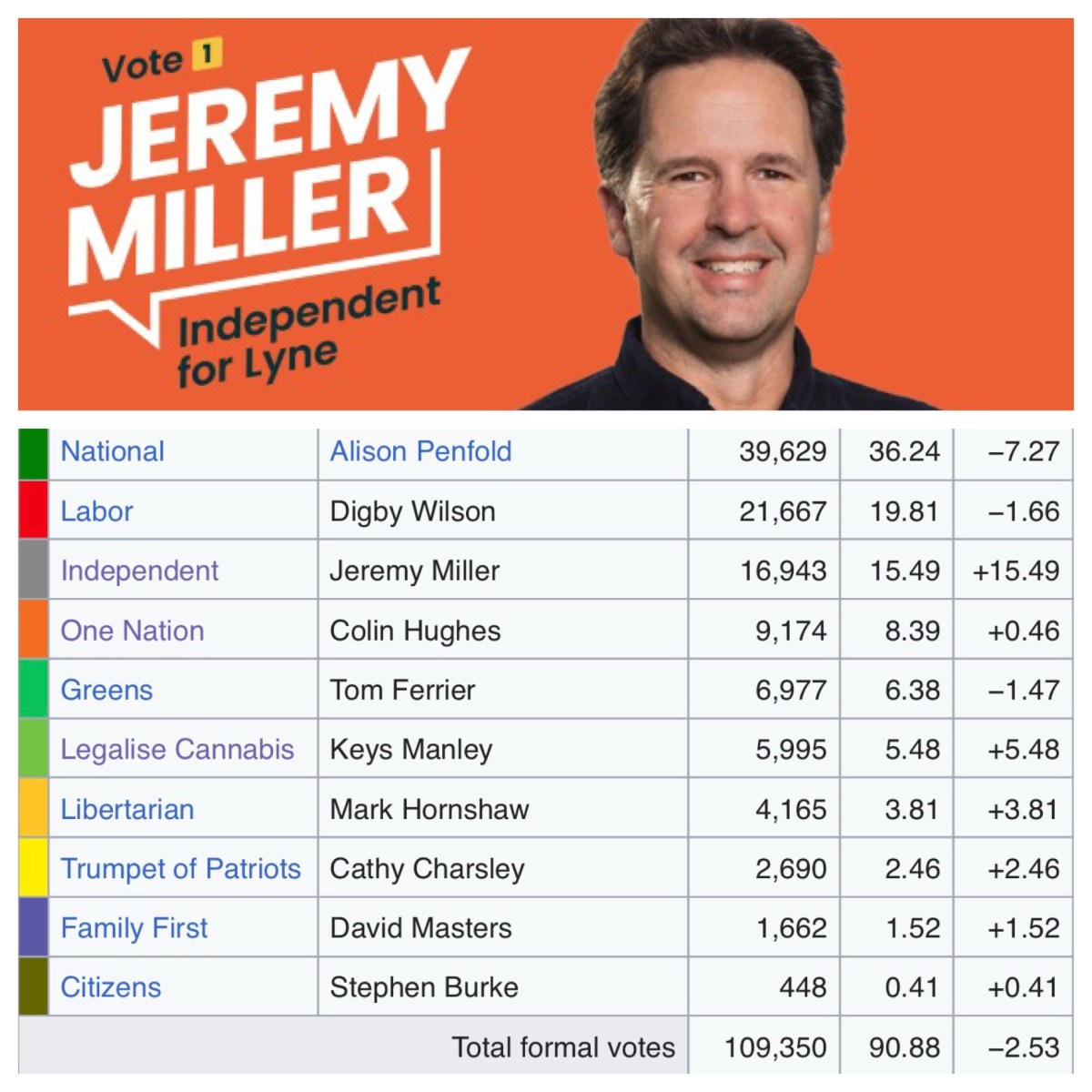

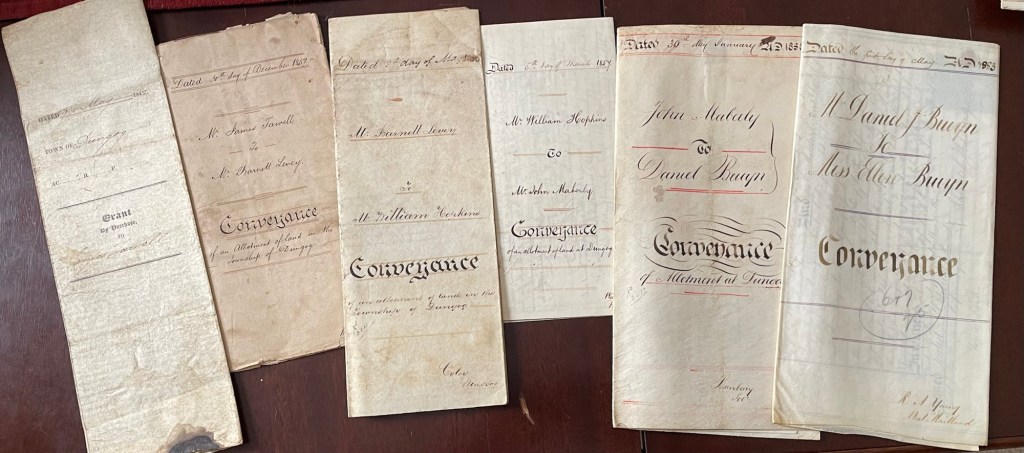

We know the names of the previous owners of this block under British colonial law from the legal documentation that came with the title to the land. And we have been able to find something about each of these owners through searching the internet and sifting the material we have found.

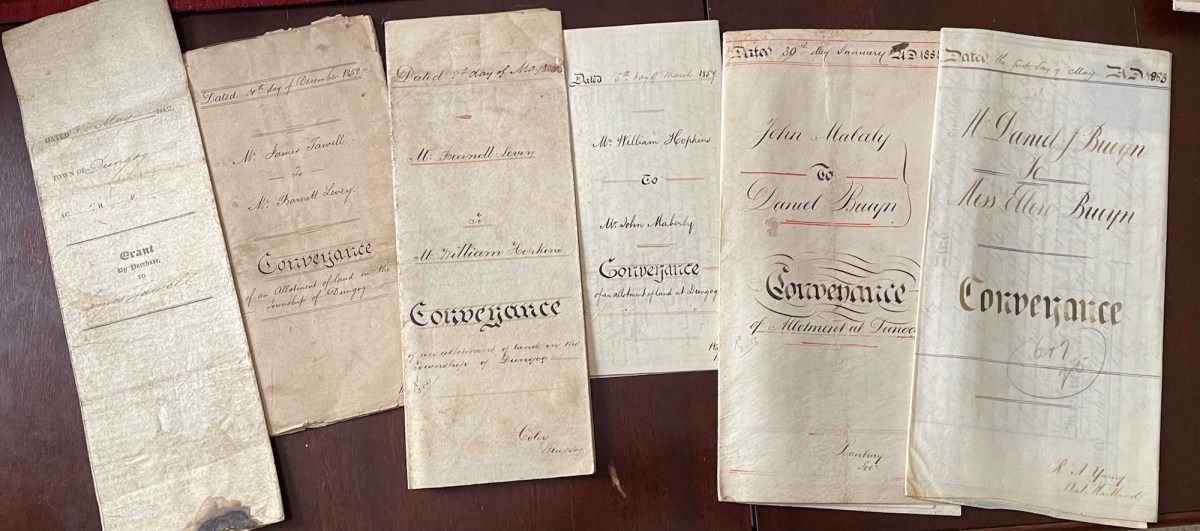

relating to land in Brown St, Dungog, which we acquired

when we purchased the house and land.

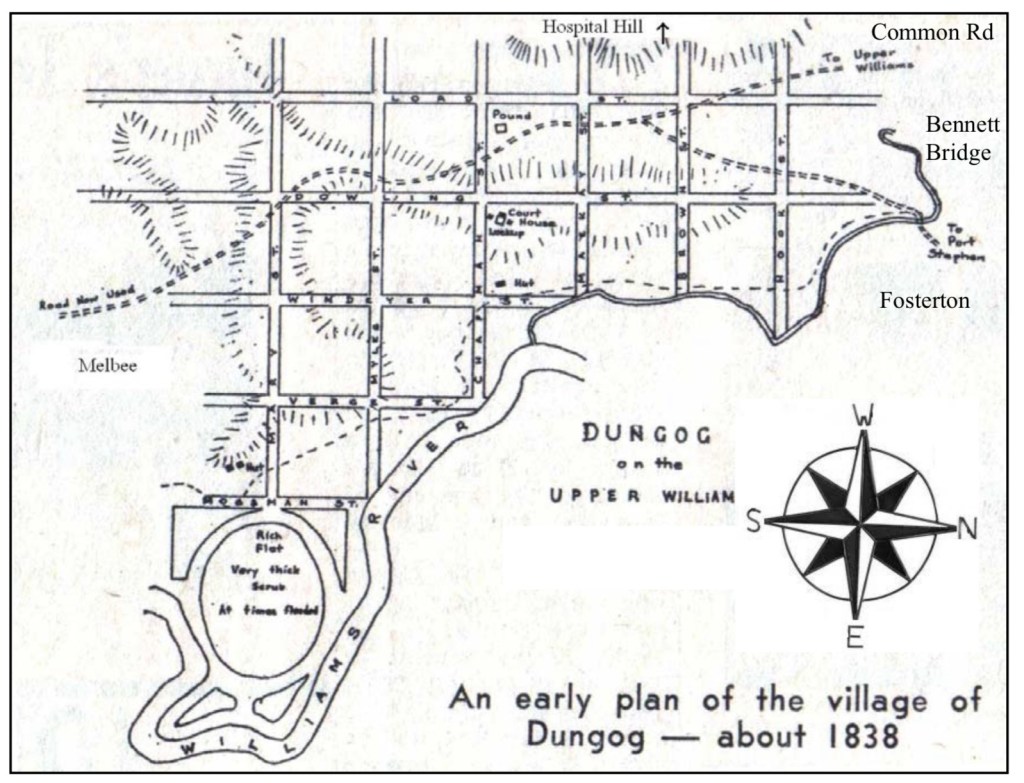

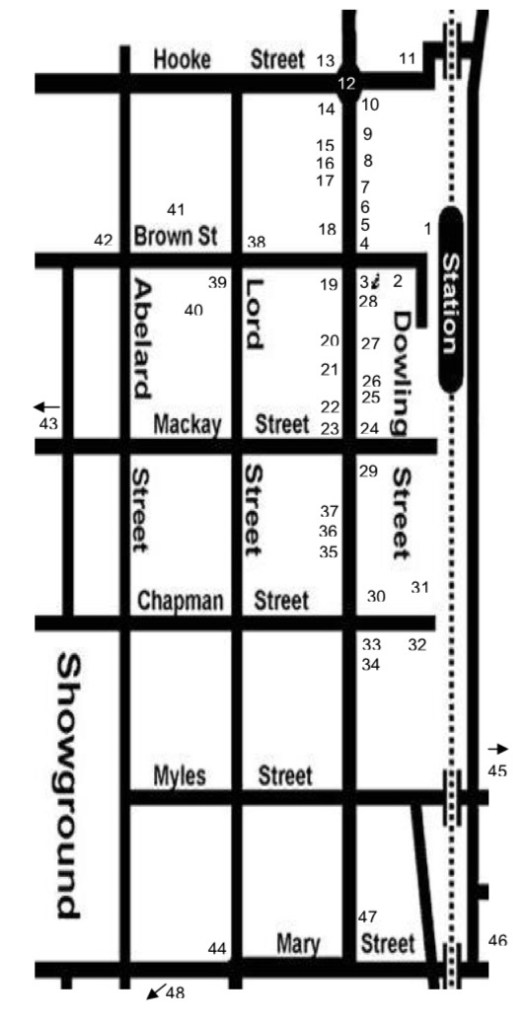

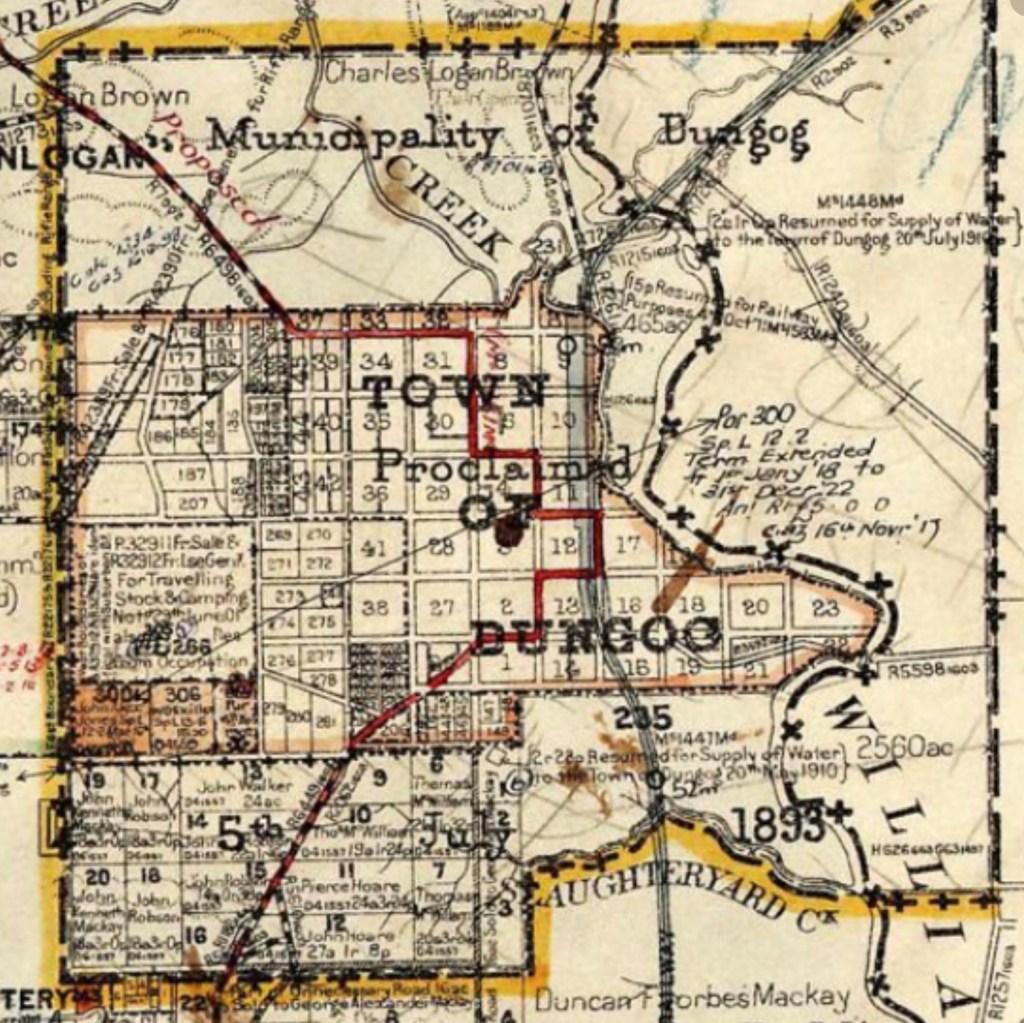

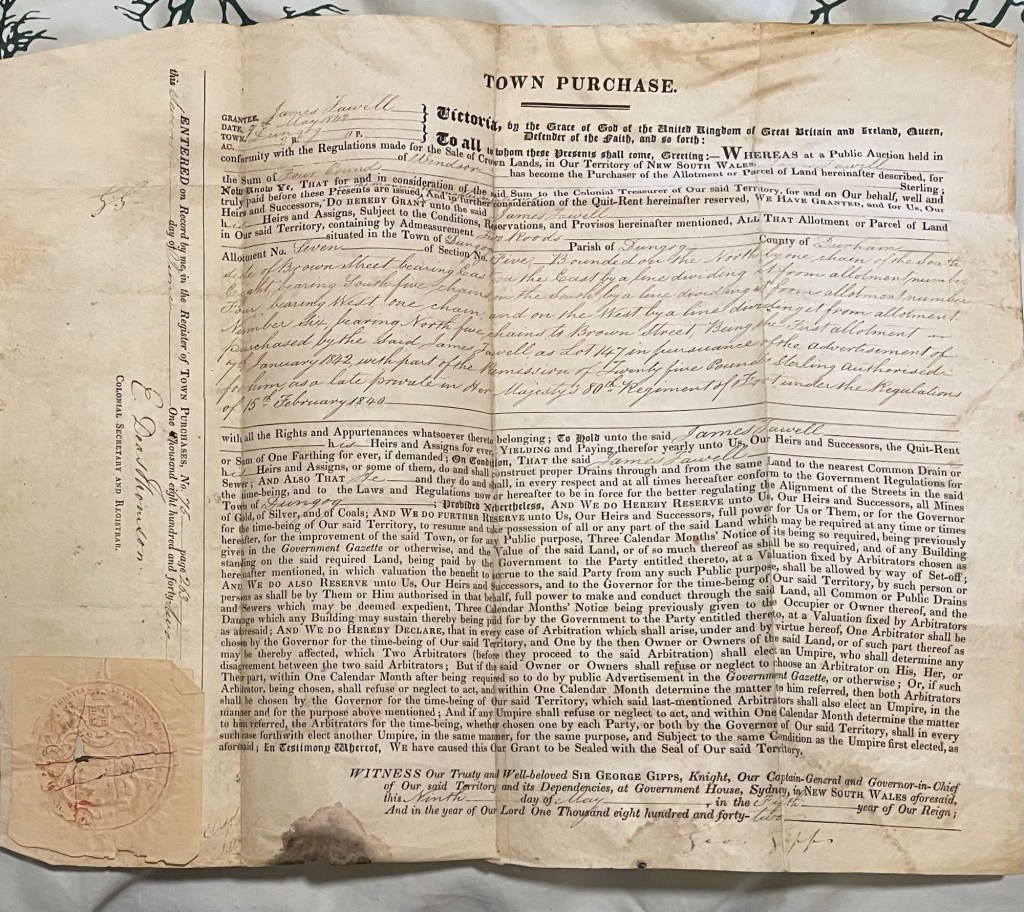

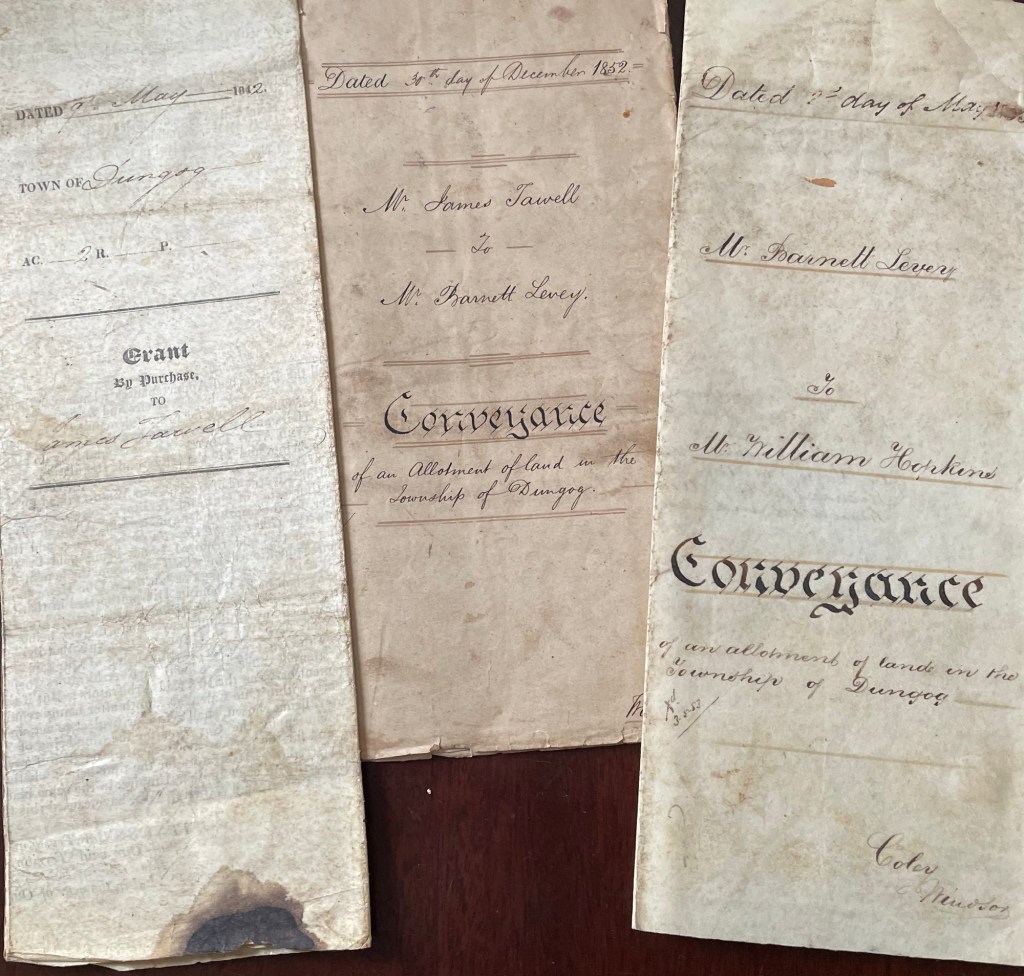

The block of land which we recently bought was originally bought under the system of colonial landholding by James Fawell on 9 May 1842. It cost him £4.0.0. The legal documentation identifies it as “Lot No. Seven Section No. Five in the Town of Dungog”. Section Five is the block bounded by Dowling, Brown, Lord, and Mackay Streets. Dowling St runs along the ridge beside the Williams River, and it developed early into the street of commerce for the town.

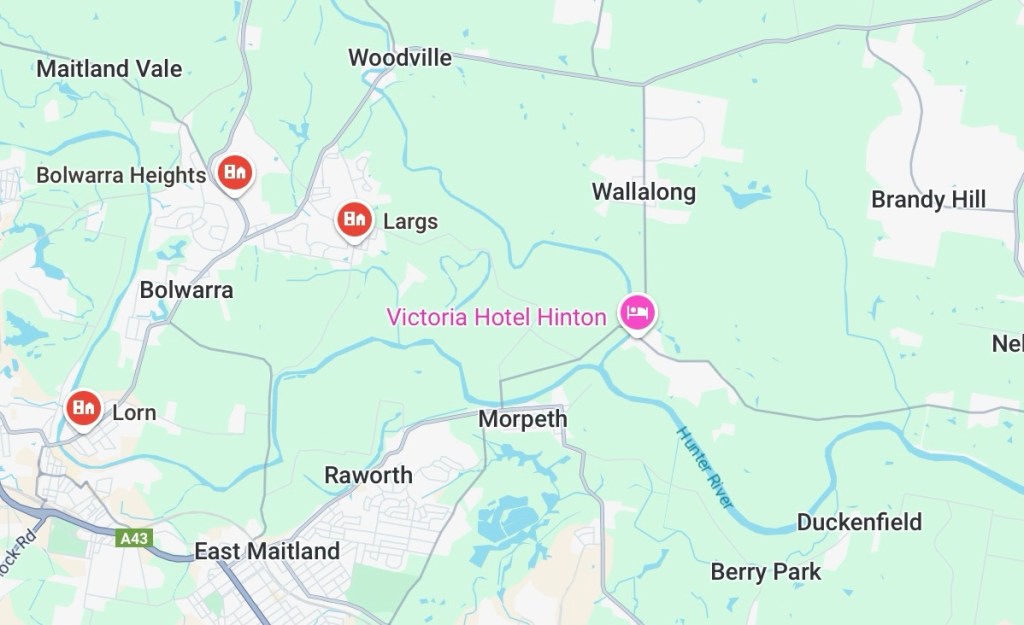

The land on Brown St that James Fawell bought is described in the legal documentation as “two roods situate in the Town of Dungog County of Durham, bounded on the North by one chain of the South side of Brown Street, bearing East on the East by a line dividing it from allotment number eight, bearing South five chains on the South by a line dividing it from allotment number four, bearing West one chain and on the West by a line dividing it from allotment number six, bearing North to Brown Street”.

Dungog, to James Fawell

All of this means it was a long block, fronting Brown St, a little more than 20 metres (one chain) wide and just over 100 metres (five chains) wide. In total, the “two roods” equates to half an acre (since one rood equals a quarter-acre).

After Fawell bought the land at Public Auction in 1842, there were a number of owners of the land over the ensuing years. The land was purchased by Barnett Levey (in 1852), sold to William Hopkins (in 1855), then sold to John Maberly (in 1857), and in the next year (1858) to Daniel Bruyn.

There is no indication from the legal papers that any of these owners either built a house on the land, or lived on the land. Indeed, Daniel Bruyn is the first owner to be identified as being “of Dungog”; those before him, apart from Fawell, all lived in Windsor. This reflects what is known of Dungog in the mid—19th century.

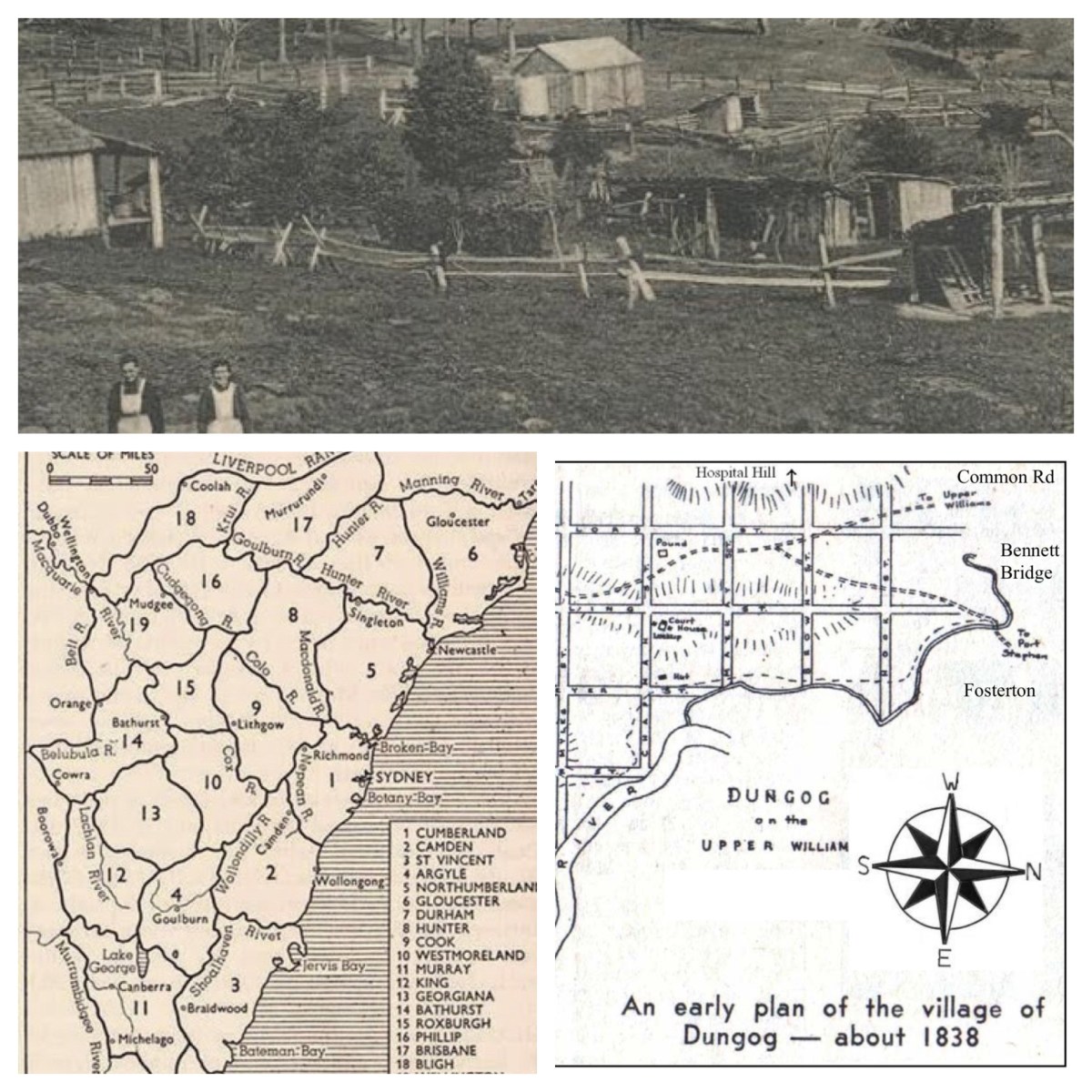

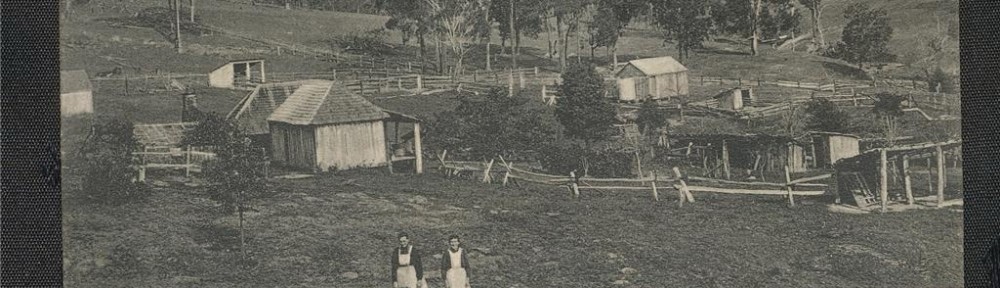

Throught the 1800s, it seems that there was relatively little building west of Lord St. The main populated area was on Dowling St and within a block either way on its various cross streets (Hooke, Brown, Mackay, Chapman, Myles, and Mary). One John Wilson, born in Dungog in 1854, is said to have described the town as a “sea of bush and scrub, with a house here and there”, and with bullock teams and drays having “to wend their way between stumps and saplings”.

Even in 1892, at the opening of Dungog Cottage Hospital on Hospital Hill to the west, the trek up was largely through open countryside. Boosted by the development of the dairy industry from the 1890s, Dungog grew more rapidly; as with all towns north of Newcastle, a further boost occurred with the arrival of the railway in 1911.

Indeed, many of the finest houses and commercial buildings still standing in the town were built from the end of the nineteenth century, into the first two decades of the twentieth century. Coolalie (206 Dowling St) and Coimbra (72 Dowling St), as well as the then Angus & Coote building (146–148 Dowling St) and the Dark stores (184–190 Dowling St) all date from this period of expansion. Which may well provide a clue regarding the house eventually built on our Brown St block of land.

History of the Williams River Valley

Who were these five men who owned, in turn, Lot Seven in Section Five of the Town of Dungog, over the 16 years from 1842 to 1858? All had their origins in England. I have been able to find out some basic information about some of them, and with some educated hunches, perhaps also about the others. It seems to me that, with the exception of the fifth of these five men, each of them bought the property in order to leverage their possession to increase their finances. Certainly, each time the land was sold, it brought a profit to the seller.

James Fawell purchased the block of land on 9 May 1842 for £4. The Grant by Purchase document states that he was using “part of the Remission of Twenty five Pounds Sterling Authorised for him as a late private in Her Majesty’s 80th Regiment of Foot under the Regulations of 15th February 1840”. This was a regiment raised in 1793 in Staffordshire; it saw action in Flanders and the Netherlands and it was part of the British force that expelled Napoleon from Egypt in 1801. The Regiment served in India from 1803 to 1817.

In May 1836 a detachment of the Regiment, led by Major Narborough Baker, left Gravesend as the guard on the convict ship Lady Kennaway. It arrived in Sydney in October 1836. 25 further detachments followed as convict guards on convict ships in the next two years. Fawell must have come to the Colony in this capacity.

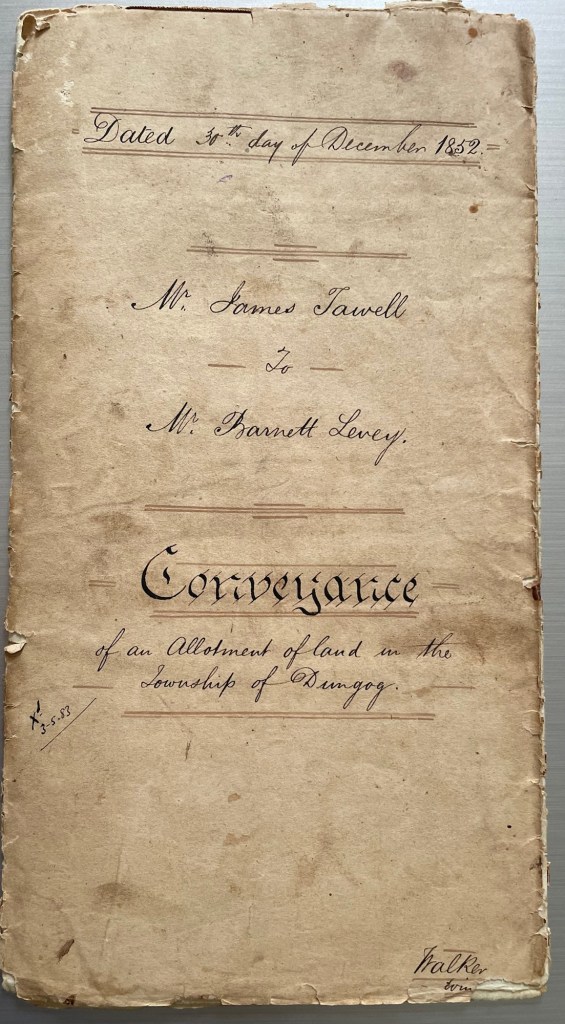

Fawell owned the land for a decade. A Conveyance dated 30 December 1852 reports that James Fawell of Windsor, Settler, sold this land to Barnett Levey of Windsor, Innkeeper, for Nine Pounds Sterling.

from James Fawell to Barnett Levey

Who was Barnett Levey? Was he one of the four children of Barnett Levey (1798–1837), theatrical entrepreneur, first free Jewish settler in NSW ?

For an account of the life of Barnett Levey snr, see https://bondistories.com/category/colonial-history/

It is an unusual name; so if this hunch is correct, Barnett jnr was born 1827 and listed in the 1828 Census with his parents. He later worked as a Teacher (1870–1896) and he died in 1907.

(Information taken from https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Levey-87)

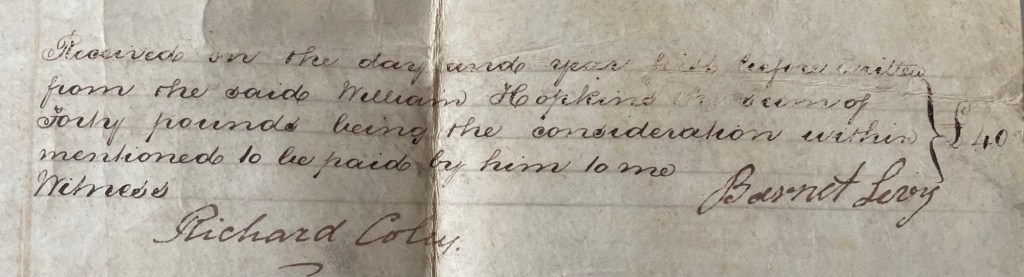

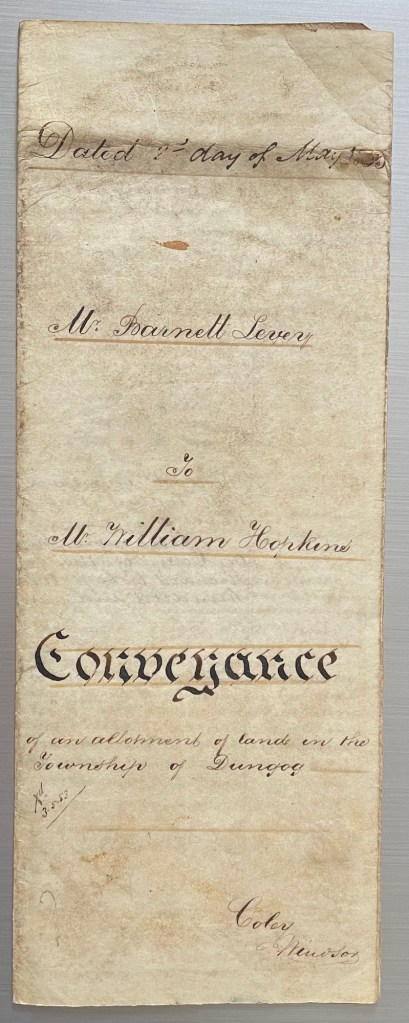

The next owner was William Hopkins. Levey held the land for less than three years; a Conveyance dated 2 May 1855 documents the transaction between Barnet Levey of Windsor, Dealer, and William Hopkins of Windsor, Miller. The land cost Hopkins Forty Pounds Sterling, so Levey had received more than three times what he paid for the land in 1852.

from Barnett Levey to William Hopkins

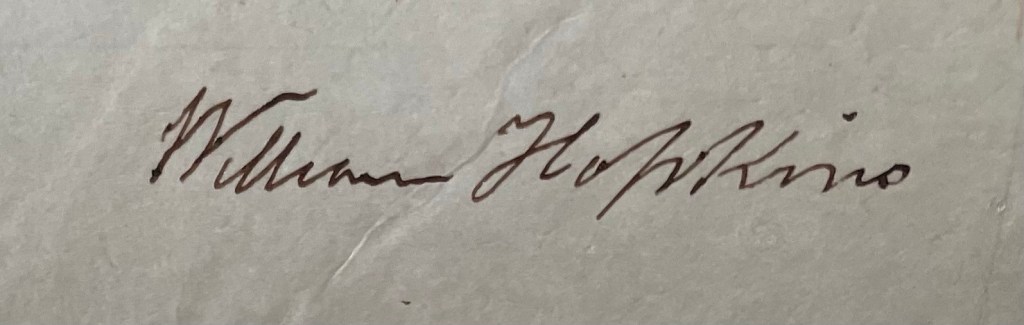

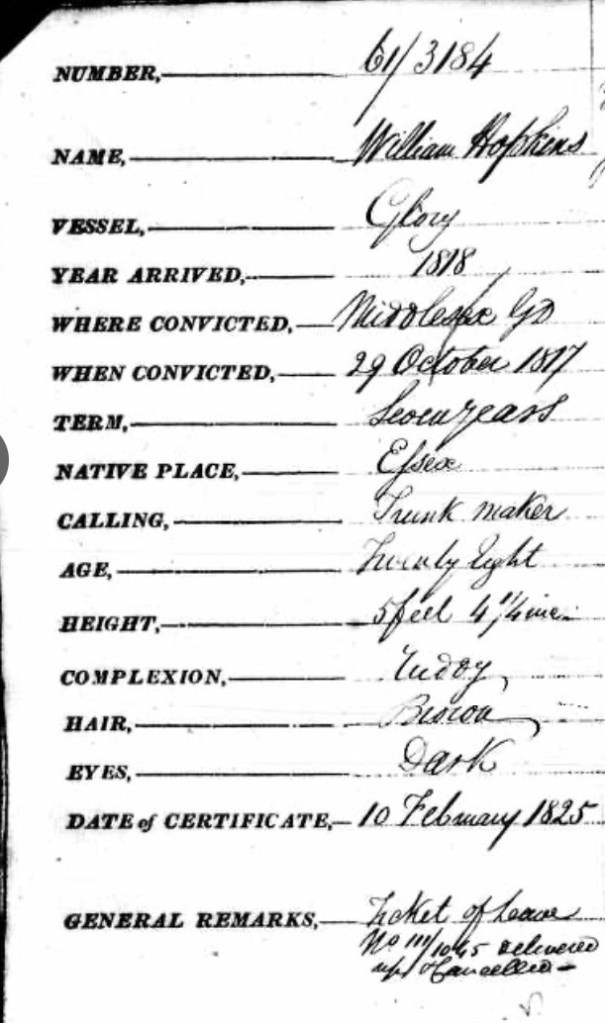

Was the purchaser of this land William Hopkins, Miller, of Windsor, who established the Fitz Roy Steam Flour Mill at 309 George Street, Windsor in the 1840s? If so, it would mean that this land was once owned by a convict who gained his Certificate of Freedom on 10 February 1825.

This William Hopkins was born in the late 1790s. He was indicted for stealing, on the 17th of October, one coat, value 20s., the goods of Henry Moule. He was (again) indicted for stealing, on the 17th of October, one tea-pot, value 5s; and two spoons, value 2s , the goods of Charles Moody. Hopkins was convicted at Middlesex Gaol Delivery for a term of 7 years on 29 October 1817. He was aged 22.

Hopkins was one of 170 convicts transported on the ship ‘Glory’, which departed in May 1818 and arrived in the Colony on 14 Sept 1818. At age 26, Hopkins was free by servitude, and became a landholder at Wilberforce. His wife at this time was Susannah Lisson, born in 1796; their children were William, 2, born in the colony, and Ann, 11 months, also born in the colony. William died and was buried on 30 Jan 1862.

(These details about William Hopkins are taken from https://australianroyalty.net.au/tree/purnellmccord.ged/individual/I76736/William-Hopkins)

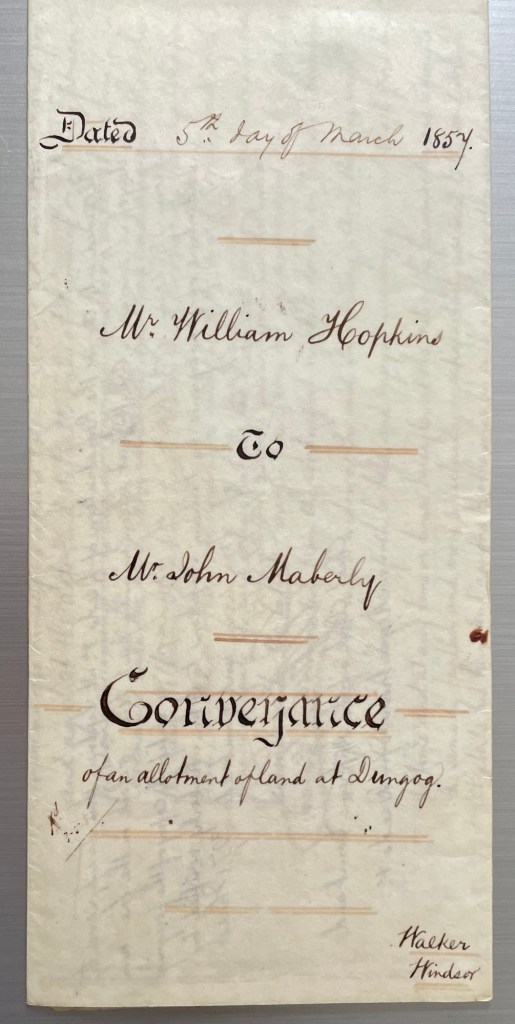

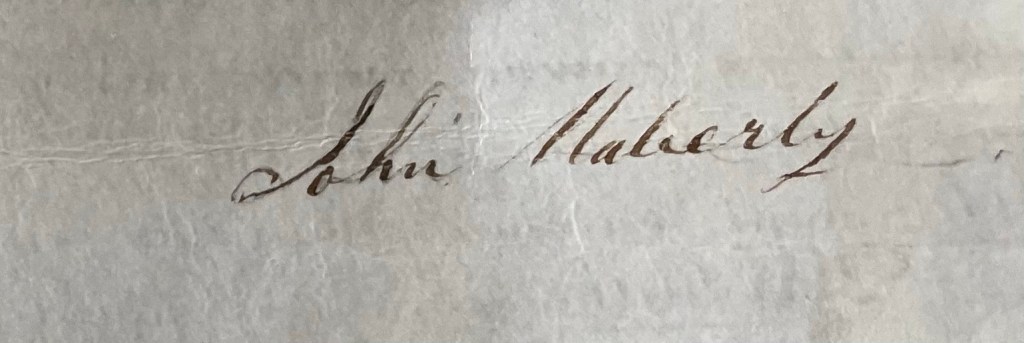

The land then had two further owners in quick succession: John Maberly in 1857, and in the next year, 1858 Daniel Bruyn. A Conveyance dated 5th day of March 1857, between William Hopkins of Windsor, Miller, and John Maberly of Windsor, Boot and Shoe Maker, states that Allotment No. Seven of Section No. Five was sold at Public Auction by Mr John Boulton Laverack, Auctioneer, for the sum of Fifty Pounds. Hopkins thus made Ten Pounds in the space of 22 months when he sold the land.

from William Hopkins to John Maberly.

John Rogers Maberly (1827–1860) was the son of convict John Maberly, a carpenter, who arrived in the Colony in 1830 on the Nithsdale), and Elizabeth Rogers. He was born on 14 Oct 1827 in Lambourne, West Berkshire and married Mary Ann Miller (1831–1918) in 1849. John Maberly died of heart disease on 18 Oct 1860 at Windsor; Mary Ann later married William Stubbs at Richmond on 21 June 1866. Stubbs was the son of William Stubbs (1796–1852), who came to the Colony on the Coromandel in 1802.

(Information taken from https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Maberly-21)

There is also another document from 1857, a Bond of Indemnity from William Hopkins to John Maberly in relation to Rebecca Levy, widow of Barnett Levy.

Within less than a year, Maberly had sold the land. In a Conveyance dated 30 January 1858 between John Maberly of Windsor, Boot and Shoe Maker, and Daniel Bruyn of Dungog, Blacksmith, the transfer was effected for a price of fifty three pounds ten shillings.

The land would stay in the Bruyn family for the next 110 years. What, then, do we know about Daniel Bruyn?

Ah, well, that’s a story for another time … … …

See earlier blog at

and subsequent posts at