How do we know about religion in the ancient world? We get lots of information from writers of the time, who either write explicitly about the religions being practised, or include material in their work that offers insights. The Old Testament contains Torah and associated literature which tells us about the development of Israelite religion and then Judaism, while the New Testament tells us about the formative period of Christianity.

Beyond those sacred texts Jewish literature continues into the rabbinic period, probing and exploring every dimension of Torah, while Christian writers of the centuries after Jesus write and debate, documenting liturgies and formulating doctrine. A whole host of pagan writers across all those time periods reveal insights into both of these religions as well into as the array of gods and goddesses who were worshipped in ancient times. We have a wealth of information!

Alongside these writers, however, there are many inscriptions from the ancient world which give us direct access into the religious world of the day. These are, by their nature, localised, individualised, focussed, even fragmentary; yet the collective set of insights from such inscriptions, alongside the written literature, deepens and widens our understanding. Here’s a brief glimpse of what we might learn.

Erecting a plaque in church is a modern phenomenon; the same was done back in antiquity. There are many instances of inscriptions found in archaeological sites in the Mediterranean region. Hellenistic inscriptions abound, serving a range of purposes—including the dedication of a holy space to a designated God, as well as a note indicating who the primary benefactor was for the erection of such a building. Letters were chiselled into a stone block before it was then attached to the wall of the temple. They were sturdy when made, and so have lasted over the centuries.

1. Temple Inscriptions

Inscriptions in pagan temples are useful for indicating the particular deity being worshipped. They usually include the name of the god or goddess who is worshipped in this space, and the name of the benefactor(s) who funded the erection of the inscription (or the whole building). In many cases, the deity is addressed with a twofold name—one indicating a Greek or Roman deity, the other either a name indicating function or a name of a local deity (in another language) who has become attached to the Greek or Roman deity.

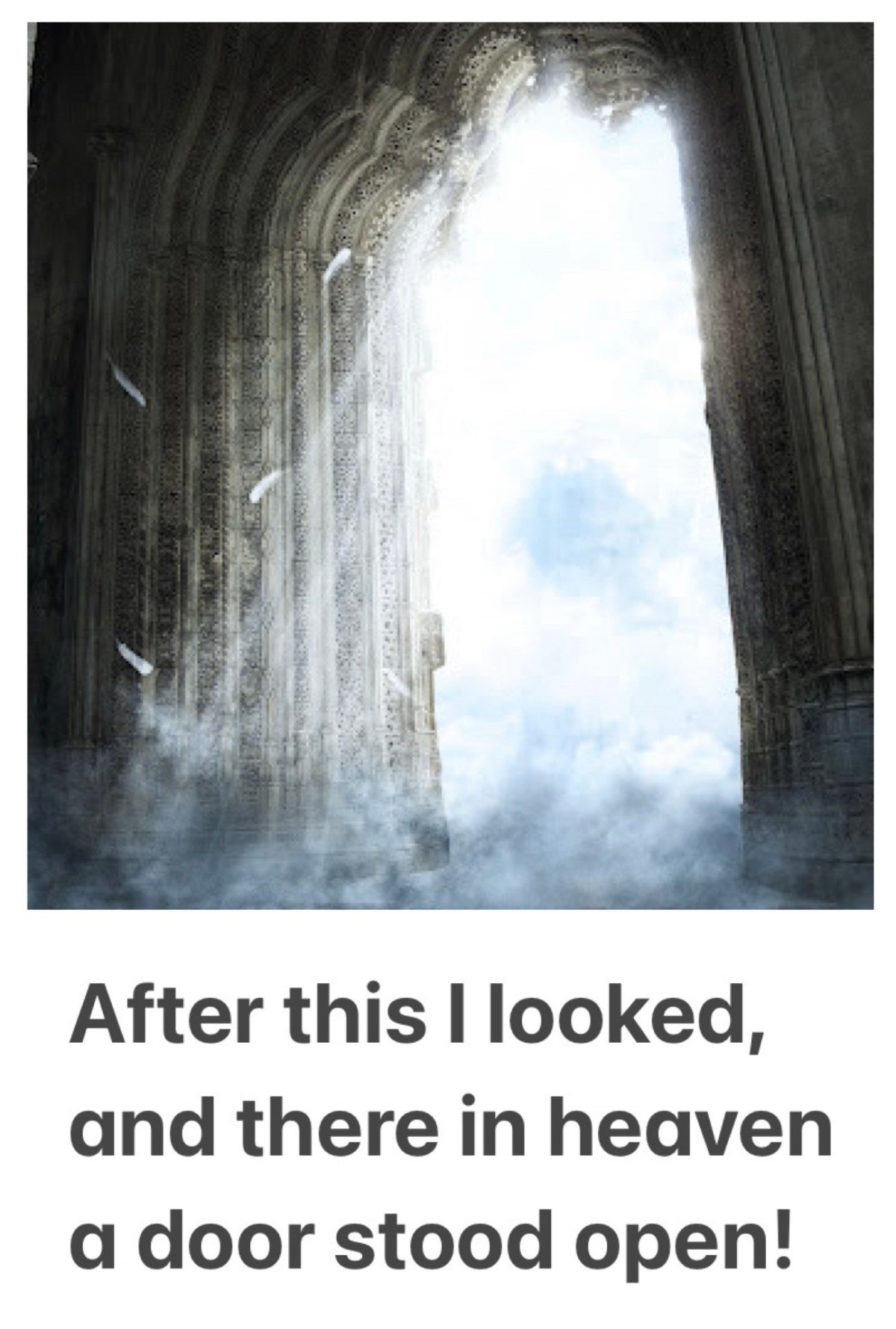

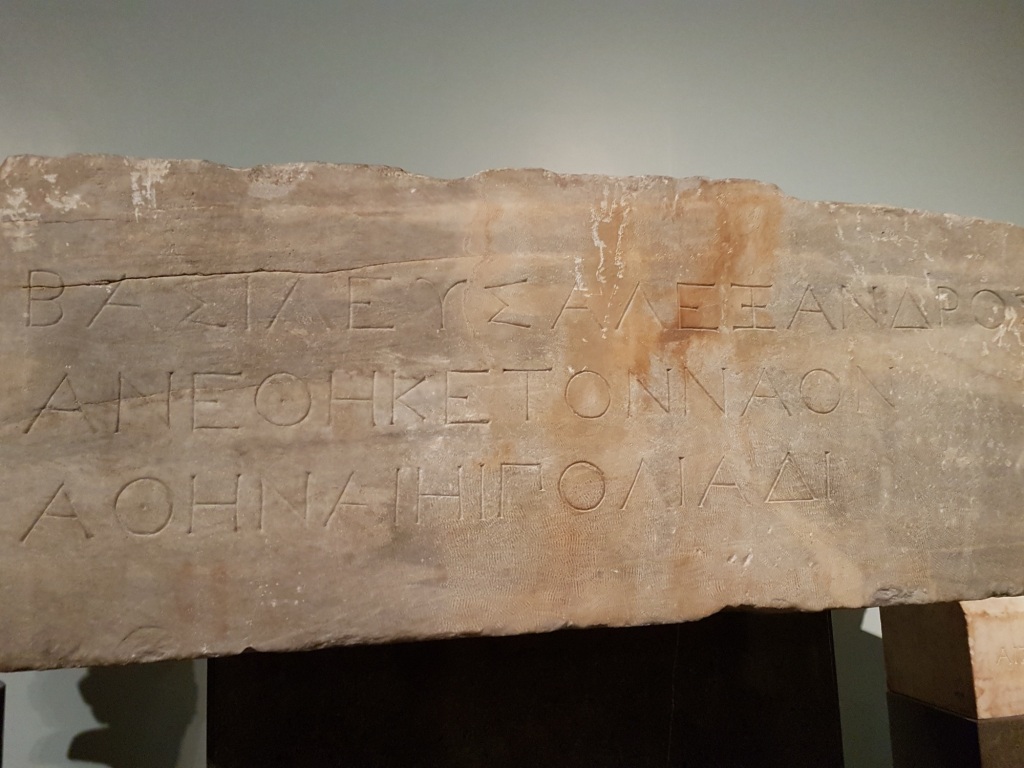

A simple example is the Priene Inscription of Alexander the Great. This is an early dedicatory inscription made by Alexander in about 330 BCE. It was discovered at the Temple of Athena Polias in Priene, in modern Turkey, during an 1868–69 archaeological exploration of Priene. It is inscribed on both sides. It reads, quite simply:

King Alexander dedicated the Temple to Athena Polias.

In this inscription, Polias is derived from polis, city, and so the dedication is most likely to Athena, protector of the city.

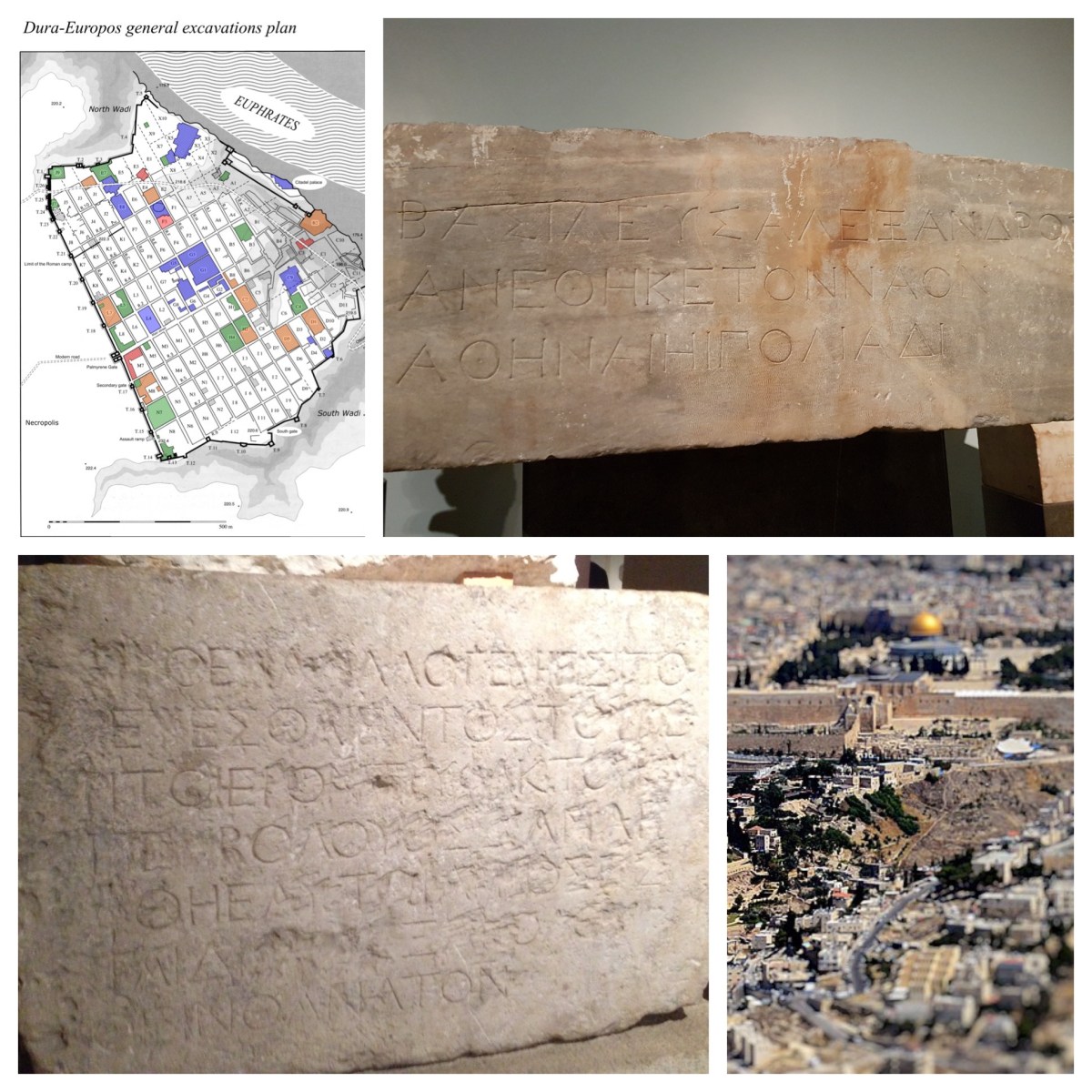

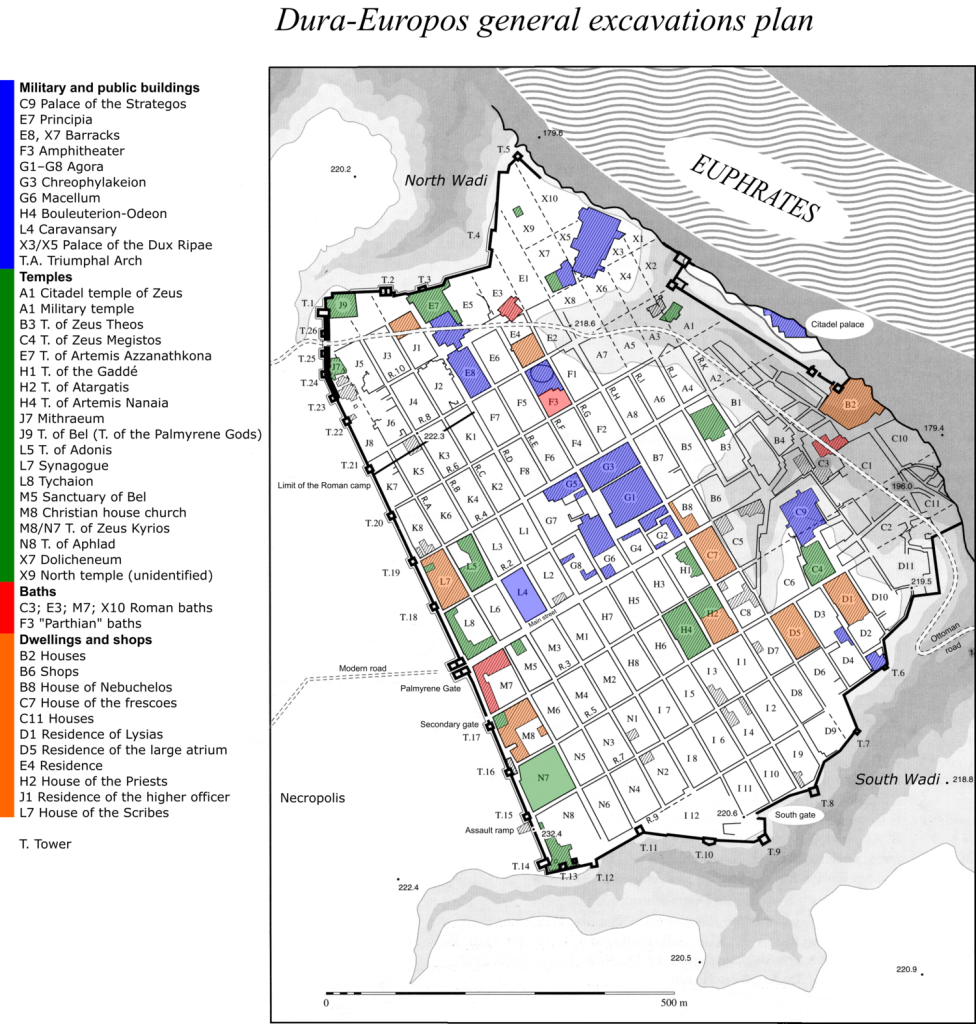

2. Inscriptions in Dura—Europos

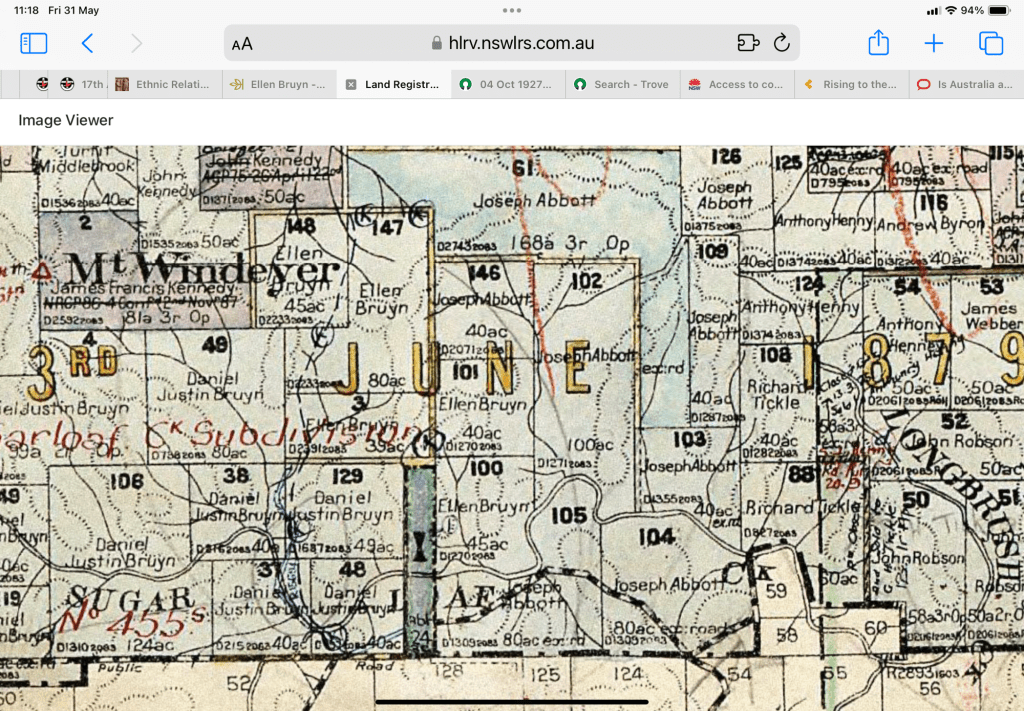

Dura—Europos was a Hellenistic settlement on the eastern edge of Alexander’s empire, in the middle Euphrates. Numerous archaeological remains were discovered in the 1920s and brought to Yale University, where a special room houses numerous inscriptions and building remains. (It was in this room that I did my graduate seminar in Epigraphy, learning how to document and translate Ancient Greek inscriptions.)

There are many temples in the city, with inscriptions dedicating those various buildings to a range of deities. It is because of these inscriptions that we know who was worshipped in each building: Zeus Theos, Zeus Megistos, Zeus Kyrios, Atargatis, Artemis Nanaia, Artemis Azzanathkona, Adonis, Tychaios, Bel, and Aphlad. There was one other temple to an unidentified deity. People were very religious at that time! The twofold names on some inscriptions reflect either a function (Theos = god, Megistos = great, Kyrios = lord) or a local deity (Nanaia was the Mesopotamian goddess of fertility; Azzanathkona was a Semitic goddess, unknown in any place other than Dura—Europos).

There was also a Jewish synagogue (with highly decorated artwork on its walls), a temple co-dedicated to Jupiter Dolichenus )with one room dedicated to Turmasgade and another room dedicated to Juno Dolichena), a Mithraeum, place where Mithras was worshipped (a bull-shaped deity who was popular amongst Roman soldiers), and a Citadel Temple of Zeus, the official worship space for the Roman troops stationed there.

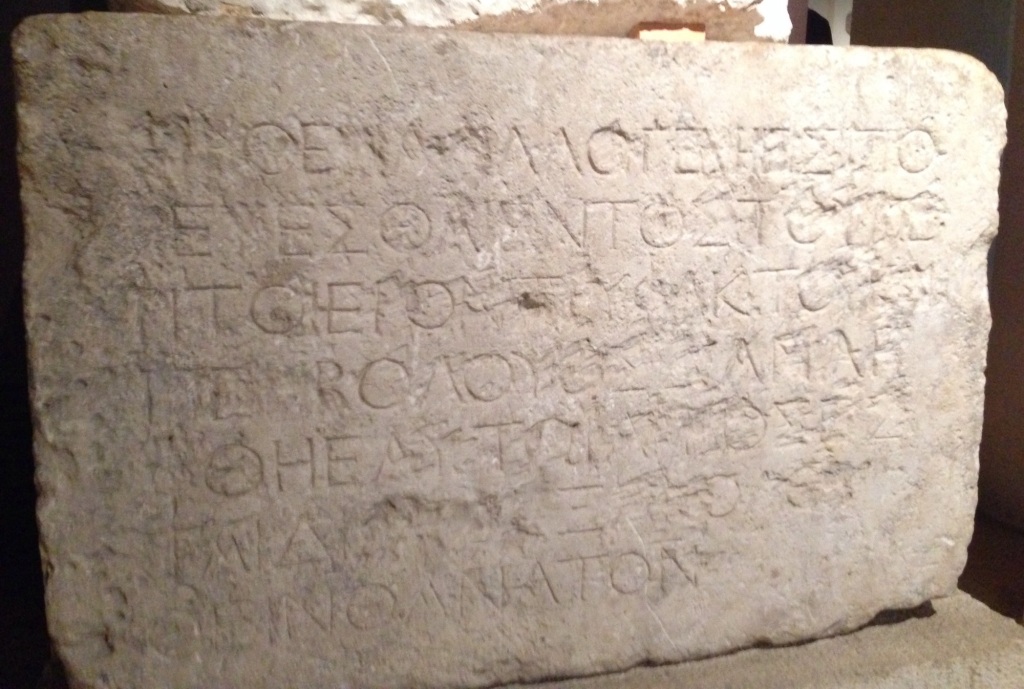

In the 2nd century BCE, while Dura—Europos was under Parthian control, a certain Alexander raised a dedicatory inscription in Greek for a renovated temple. His father had originally built it, but Roman soldiers had stolen its doors, thereby prompting Alexander to replace them and enlarge the temple itself.

In this inscription Alexander initially described himself as Alexander, son of Epinikos, but he subsequently called himself Ammaios, this same Alexander. Alexander is a Greek name—presumably his birth name—whilst Ammaios is a Semitic name.

The dedication is to Artemis, Greek goddess of the hunt and sister of Apollo, who is also given the name Azzanathkona, a Semitic goddess otherwise unknown. One leading scholar identifies her with Atargatis, a fertility goddess in Syria. So it seems that this inscription indicates that Alexander, with origins in a Greek-speaking area, had been sent east to Dura (perhaps as a soldier?), become enculturated over time (maybe even married a local woman, as many soldiers did), and adopted a local name, Ammaios, as well as becoming a devotee of a local goddess, Azzanathkona. All this from one inscription!

Yale University, 1997

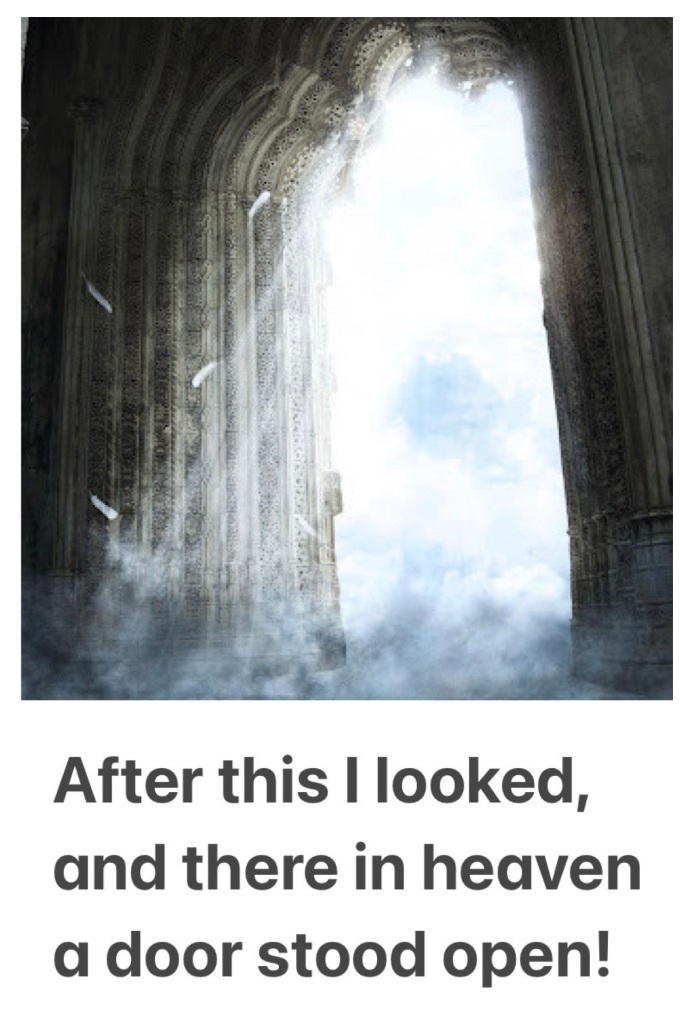

3. Jerusalem Temple Inscription

Jews also made and erected inscriptions. In Jerusalem, there was an inscription of seven lines that was placed outside the sanctuary of the Second Temple, warning Gentiles not to proceed any further. It is dated between 23 BCE and 70 CE. It was found in 1871 just outside the Gate to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Some letters still contain traces of the red paint that would have highlighted the whole text.

No stranger is to enter / within the balustrade round /

the temple and / enclosure. Whoever is caught /

will be himself responsible / for his ensuing / death.

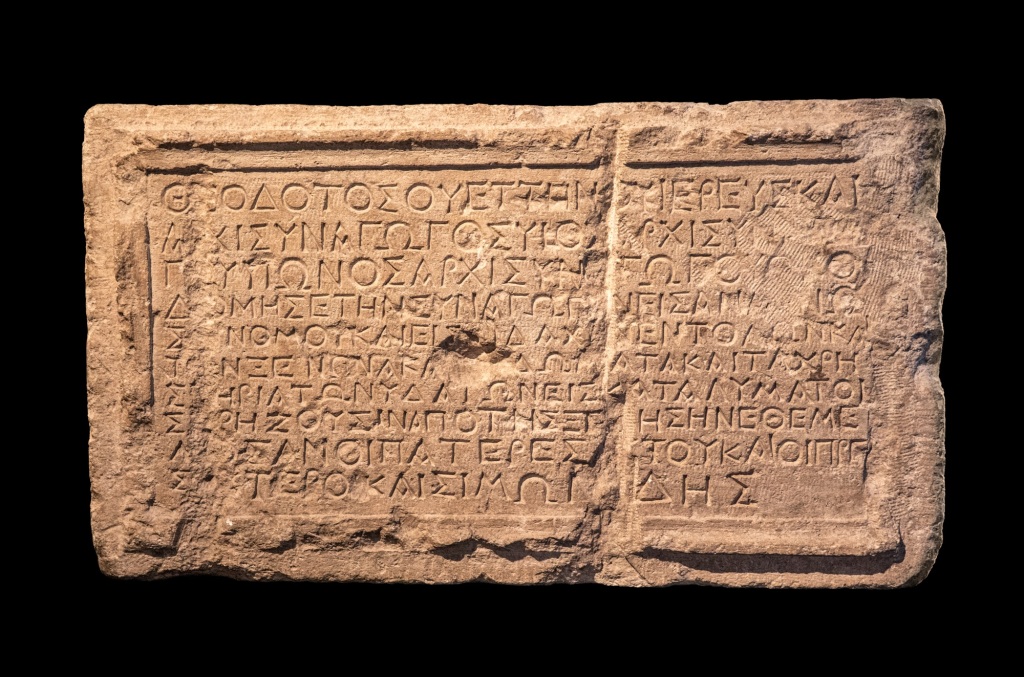

4. Synagogue Inscriptions

Synagogues also include inscriptions, some identifying the purpose of the building or the name of the benefactor who paid for its building. The Theodotus Inscription is a well-known example. It has ten lines, 75cm x 41cm, and was found in 1913 in a dig in Wadi Hilweh, in East Jerusalem. It was erected by Theodotus, the patron and leader of the synagogue. The inscription identifies him as benefactor and gives details of the whole building complex; it’s an important insight into the fact that ancient synagogues were not just places of worship and teaching, but also places of hospitality for visitors.

Theodotos son of Vettenus, priest /

and head of the synagogue (archisynágōgos),

son of a head of the synagogue, /

and grandson of a head of the synagogue, /

built the synagogue /

for the reading of the law and for

the teaching of the commandments, /

as well as the guest room, the chambers, /

and the water fittings as an inn /

for those in need from abroad,

the synagogue which his fathers /

founded with the elders / and Simonides.

5. Christian inscriptions.

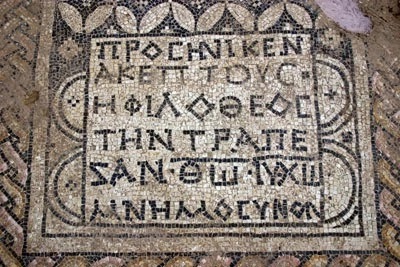

There are Christian inscriptions in church spaces that have been excavated, increasing in numbers over the centuries. The Akeptous Inscription is one of a number of inscriptions found in the mosaic floor of a 3rd century church. It was discovered in 2005 while digging inside the Megiddo Prison in Israel. There are six lines in this simple inscription:

A gift / of Akeptous, / she who loves God, /

this table [is] / for God Jesus Christ, / a memorial.

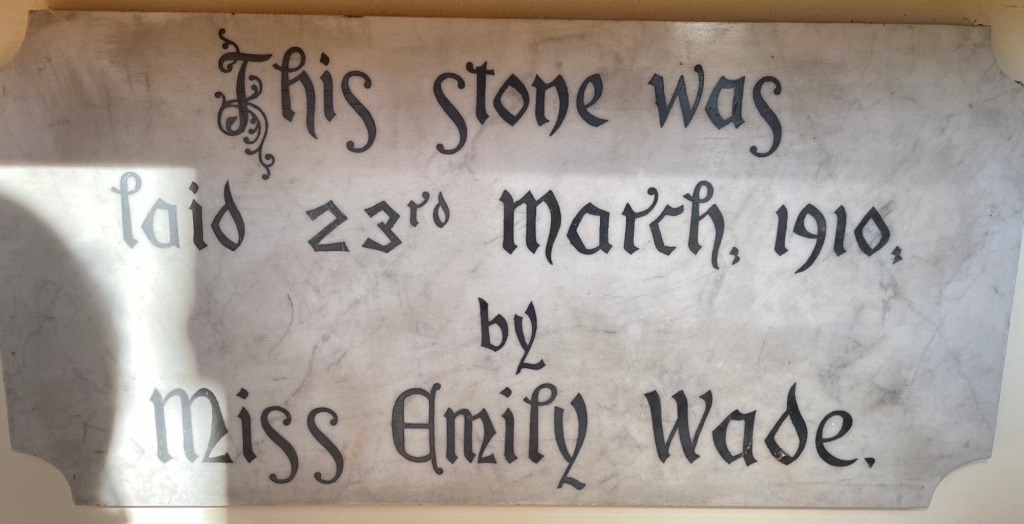

This reminds me of many churches where I have been, where a small plaque is placed outside the building, marking its opening.

There are also many churches that have plaques inside; such a plaque may indicate that it was erected in memory of a named person, and it can be attached to the the wall, the communion table, a chair in the sanctuary, a lectern, or even (as in the case where I currently worship) the light switch that turns on the light behind the central cross!

6. Women in Jewish synagogue inscriptions.

Scholar Bernadette Brootten wrote a groundbreaking book, Women Leaders in the Ancient Synagogue: Inscriptional Evidence and Background Issues (published in 1982). Brooten identified nineteen Greek and Latin inscriptions that name women with the titles “head of the synagogue,” “leader,” “elder,” “mother of the synagogue,” and “priestess”.

The inscriptions have been found by archaeologists in synagogues from the Roman and Byzantine periods; they range in date from 27 BCE to the sixth century CE and were found in Italy, Asia Minor, Egypt, and Palestine. So they cover a broad range of dates and locations.

Brootten argues that in these inscriptions the women leaders are not simply “honorary” leaders (as some dismissively claim); she considers that they identify actual leaders, who had specific leadership functions. For instance, a white marble sepulchral plaque from Gortyn in Crete dating to the 4th or 5th century CE remembers Sofia:

Sofia of Gortyn, elder (presbytera)

and head of the synagogue (archisynagōgissa)

of Kissamos [lies] here.

The memory of the righteous one for ever. Amen.

Centuries earlier, a second-century CE inscription from Smyrna mentions a woman named Rufina who was a synagogue ruler. The inscription reads:

Rufina, a Jewess synagogue ruler (archisynagōgos),

built this tomb for her freed slaves

and the slaves raised in her household.

No one else has a right to bury anyone here.

In the inscriptions found and discussed by Brootten, there are three Greek inscriptions in which women have the title archisynagōgos or archisynagōgissa (arch– plus “an element formed from the institution over which the officer stands, in this case the synagogue”).

In another inscription, Peristeria is called archēgissa, “leader.” Six ancient Greek inscriptions have been found in which women carry the title “elder” (presbytera or presbyterēsa) and one in which a woman is called presbytis. Women are called “mothers of the synagogue” in six Greek and Latin inscriptions and “priest” (hierea or hierissa) in three Jewish inscriptions.

(Summary taken from a review of the digital [2020] edition of the book by Elizabeth Anne Willett, https://www.cbeinternational.org/resource/book-review-woman-leaders-in-the-ancient-synagogue/ )

Brootten also notes that various biblical references, as well as writings from Jewish historian Josephus and rabbinic teachings, indicate that Jewish women were present and often prominent in synagogues, and they did not sit separately from men. She reviews the reports of quite a number of archaeological sites where synagogues existed, and concludes that “the vast majority of ancient synagogues in Israel do not seem to have possessed a gallery, and there is no archaeological or literary reason to assume that side rooms were for women”.

Likewise, she notes that “there is no Diaspora synagogue in which a strong archaeological case can be made for a women’s gallery or a separate women’s section. The analogy of a separate room as a woman’s section in modern synagogues is anachronistic.” That puts paid to separation by gender in synagogues in antiquity.

Brootten’s work is important for understanding the biblical stories of Lydia, who appears to have been the leader of a synagogue (“place of prayer”) in Philippi (Acts 16:13–15) and quite a number of other women who are identified as leaders of faith communities in Acts: Priscilla in Ephesus (18:26), Tabitha in Joppa (9:36), Mary the mother of John Mark in Jerusalem (12:12), and possibly Damaris in Athens (17:34); as well as women so identified in the letters of Paul: Phoebe in Cenchraea (Rom 16:1–2), Prisca (and Aquila) in Ephesus (1 Cor 16:19) and also in Rome (Rom 16:3–5), Euodia and Syntyche in Philippi (Phil 4:2), Apphia (with Philemon and Archippus) in Colossae (Phlm 1), Nympha in Colossae (Col 4:15), and possibly Chloe in Corinth (1 Cor 1:11) and Junia in Rome (Rom 16:7); and 2 John (“the elect lady”).

See more at https://margmowczko.com/new-testament-women-church-leaders/