The New Testament was written in a context where “magic” and “divination” were regular aspects of daily religious life. Belief in an array of deities in an otherworldly realm was complemented by the understanding that it was possible to communicate with such entities—that is, to “divine the will of the gods”—and also to change or modify human behaviour in ways that related to what was learnt through such divination—that is, to perform “magic” through a variety of means.

There is evidence aplenty for this in the New Testament itself. The Gospels report, not only that Jesus communicated with God through prayer, in acts of “divining the will” of his heavenly Father, but also that he performed acts of healing and exorcism which changed the life of individual people, actions which many would have regarded as “magic”. There are also accounts of people who encountered God in dreams or through the visitation of angels; they also were engaging in “divination”.

Such “divination” continues in Luke’s second volume, Acts, recounting the formation and development of communities following “the good news about Jesus” which engaged in “divination” (in prayer and worship) and practised “magic” (through healings and exorcisms). Paul’s letters also give some indication of his abilities in this regard.

The New Testament thus attests to the widespread belief that it was possible, both to contact the divine realm and have communications from them, and to interfere in human behaviour through means generally regarded as “magical”.

In what follows, I draw particularly on the research of my wife, Elizabeth Raine, into the Hebrew Scriptures, the Greek magical papyri, and the practices of ancient magicians, and on my own research from some time ago into “divination” and oracles in the Hellenistic world.

The spread of “magic” in the Hellenistic world

The Greco-Roman world was full of “magic”. In the Encyclopedia of Religion and Society (1998), William Swatos and Peter Kivisto define magic as “any attempt to control the environment or the self by means that are either untested or untestable, such as charms or spells”. This is a somewhat modernist definition, driven by the scepticism of post-Enlightenment rationalism. In the ancient world, magic was a widely-accepted phenomenon.

There is plentiful evidence from ancient Greece, Rome, and Egypt about the practice of magic, from amulets and inscriptions that provide formulas to invoke deities, prayers to offer for health, safety, and all manner of needs, oracle sites where people could go to seek answers from the gods to their various petitions, travelling soothsayers who would provide “words from the gods” (for a price), blessings to be prayed for people and household, and curses to be said over enemies.

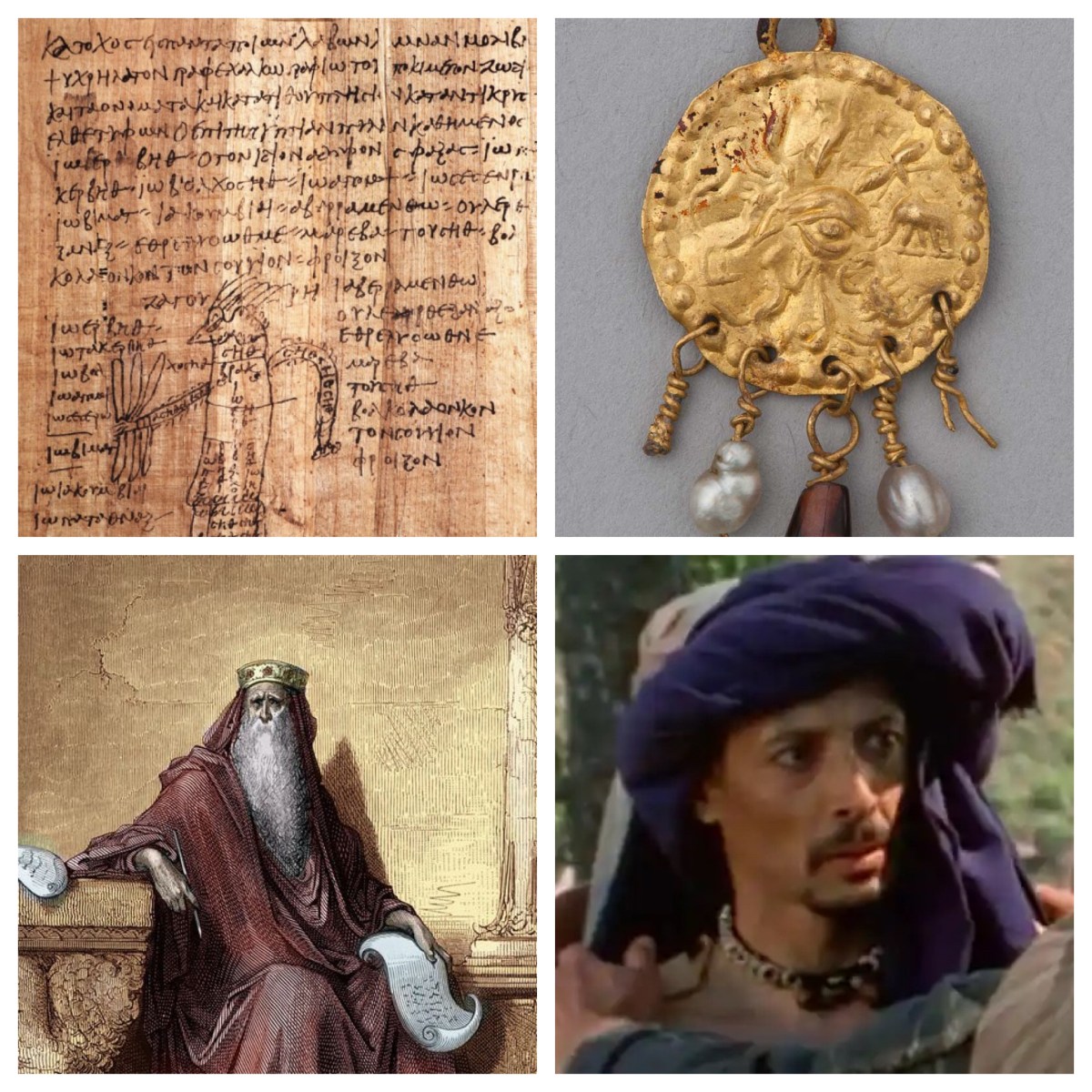

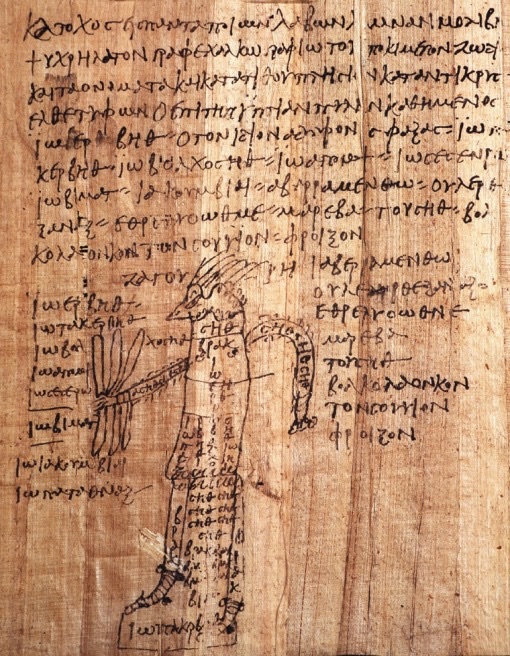

In the hellenised world after Alexander the Great, Greek was the common language of trade and commerce—but also of religion. Many Greek papyri documents that survive (the so-called Greek magical papyri) as well as various manuscripts attest to the various techniques employed by magicians and healers. Touch was often employed by such people, along with the utterance strange words from foreign languages, or indeed simply gibberish words, and ecstatic states, as the means of effecting healings in others. Multiple names were employed for addressing the deities (many made up names, or taken from tongues foreign to the speaker).

(You can read some examples at https://hermetic.com/pgm/index and explore a technical academic analysis of these papyri at https://archive.org/details/TheGreekMagicalPapyriInTranslation/page/n9/mode/2up)

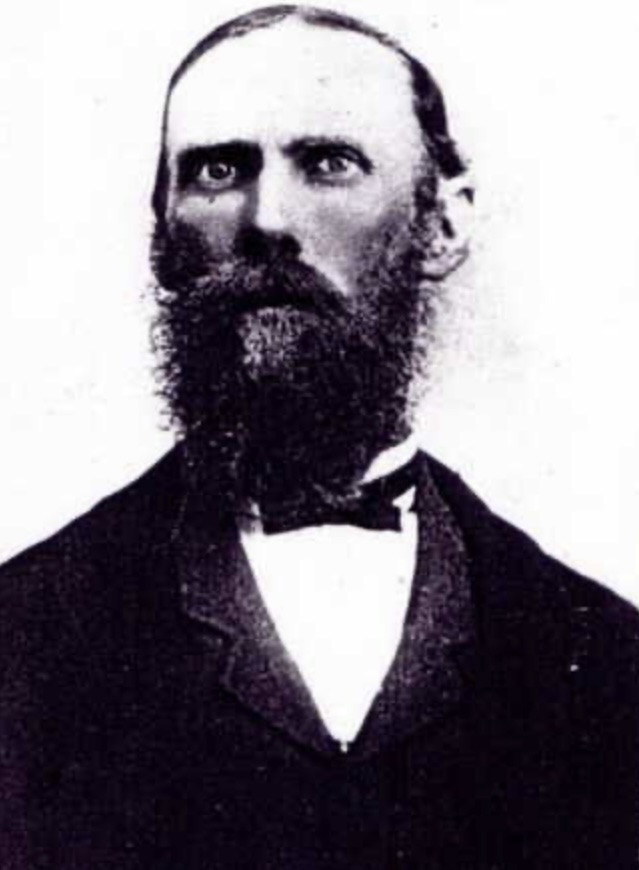

Evidence from many archaeological sites today shows that right across the ancient Mediterranean world there were amulets which were used also for “magical” purposes. These amulets most often were used for “apotropaic” purposes—that is, to protect the wearer by warding off evil forces. Many were engraved with the text of a spell to be chanted, or with an image of a deity to whom the petition in the spell might be offered.

in the Hellenistic period

During the Hellenistic period, there were a number of oracular sites to which people could travel, to place their requests before the deity or deities in focus at those sites. Delphi was the best-known of these places, where the Pythia, the priestess of Apollo, could be consulted. At Dodona, it was Zeus Naios who was able to be petitioned; other sites of significance included Cumae, near Rome, where the Sibyl offered prophetic words; Olympia, to consult Zeus; Paphos, where the oracle of Aphrodite was located; and countless other sites of local significance. There were also travelling soothsayers who, for a price, would read entrails or produce oracular sayings relating to the person asking.

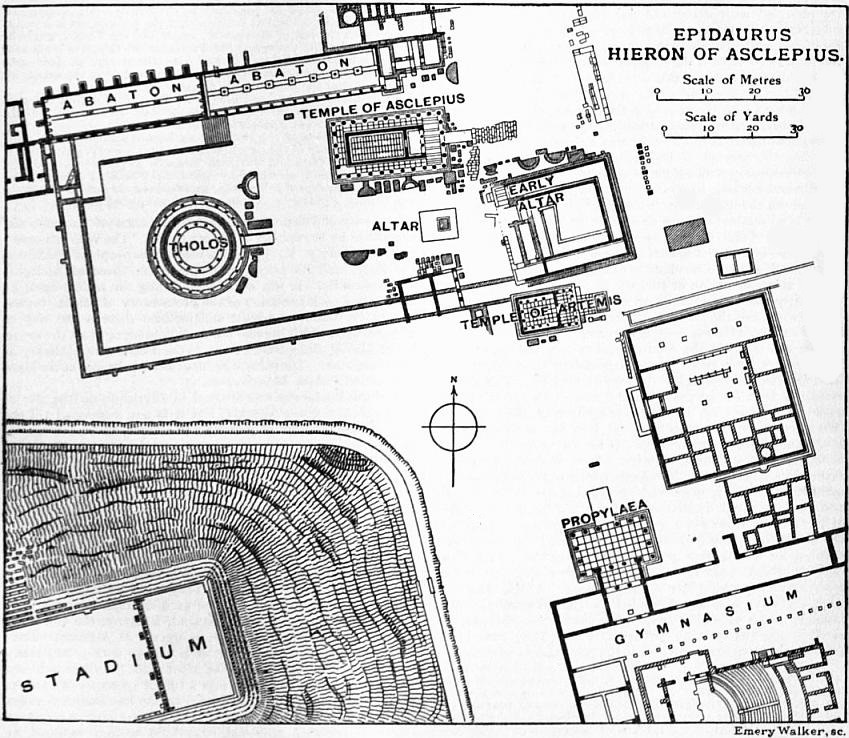

At Epidauros in Greece, a major Asclepion provided facilities where supplicants could bring offerings to Asclepius, the god of healing; then sleep in a sleeping chamber, hoping to dream, so that the god could speak directly to the supplicant. A complex system of offerings was overseen by a large staff of priests; the whole complex was quite an enterprise! Undergirding it was the form belief that, once appropriate steps had been taken, the god would be contacted and would communicate with the person seeking their healing.

Divination (“divining the will of the gods”) was practised in so many ways that the Roman statesman and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero wrote a comprehensive two-volume textbook On Divination in which he treated the various means of divination that were used at the time. In this book, Cicero engages in a philosophical debate with his brother, Quintus.

He allows Quintus to set forth his sympathetic appreciation of a range of methods of divination—auguries, auspices, astrology, lots, dreams, and various species of omens and prodigies—before he then offers his own “scientific” disputation with many of them, drawing particularly on the philosophical critique put forth by his contemporary, the philosopher Cratippus of Pergamon. Philosophical scepticism about magic existed alongside of popular adulation of the craft.

Jewish attitudes towards magicians

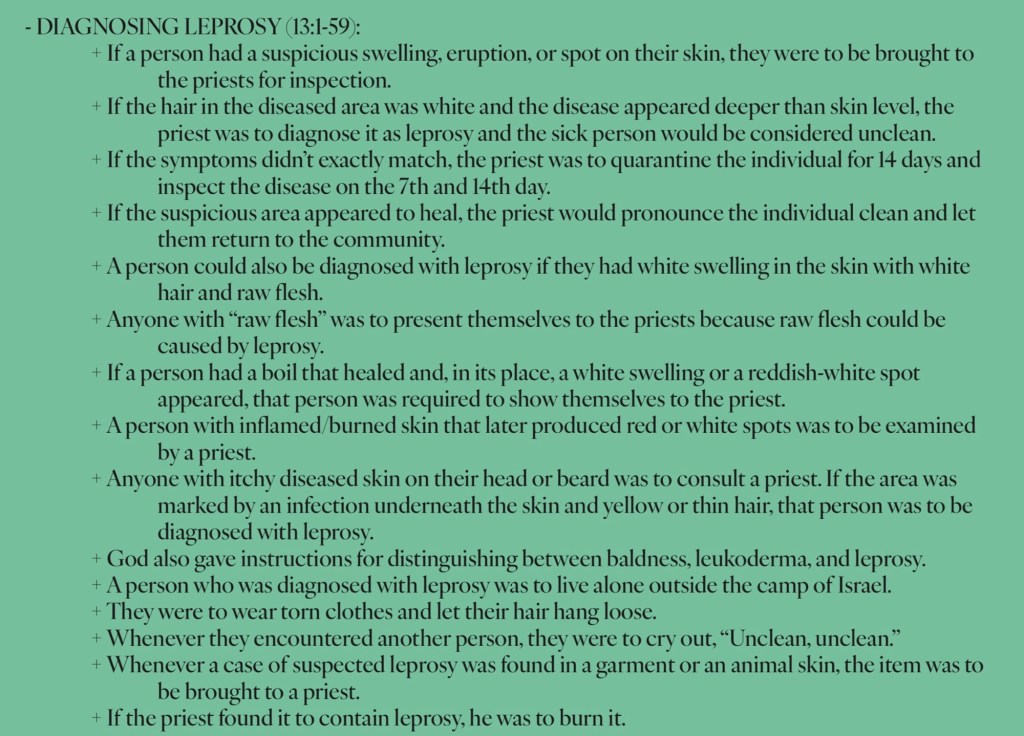

Passages in Hebrew Scripture forbid magic. In Leviticus, one commandment is quite clear when it states: “Do not turn to mediums or wizards; do not seek them out, to be defiled by them: I am the LORD your God” (Lev 19:31). Sure enough, in a story told in 1 Samuel, we learn that “Saul had expelled the mediums and the wizards from the land” (1 Sam 28:3)—only to learn a little later that when he saw the massed army of the Philistines, Saul had lamented that he had no means of divination as to what would transpire, “not by dreams, or by Urim, or by prophets” (1 Sam 28:6). So he instructed his servants to find him “a woman who is a medium, so that I may go to her and inquire of her” (1 Sam 28:7).

Excerpt of The Shade of Samuel Invoked by Saul (1857)

painted by Nikiforovich Dmitry Martynov

The servants told him “there is a medium at Endor”, so he disguised himself and went to her by night—but she sees through his disguise and also sees “a divine being coming up out of the ground” who had the appearance of “an old man … wrapped in a robe” (1 Sam 28:8–14). Saul immediately recognised this figure as the prophet Samuel, who had died back in ch.25. Saul consults Samuel and learns of his fate (1 Sam 28:15–19). And so “the witch of Endor” (as she is popularly known) proves to be of value.

In the long speech attributed to Moses in Deuteronomy, we find the command, “no one shall be found among you who makes a son or daughter pass through fire, or who practices divination, or is a soothsayer, or an augur, or a sorcerer, or one who casts spells, or who consults ghosts or spirits, or who seeks oracles from the dead” (Deut 18:10–11). Then follows a note that “although these nations that you are about to dispossess do give heed to soothsayers and diviners, as for you, the Lord your God does not permit you to do so” (Deut 18:14). That’s pretty clear!

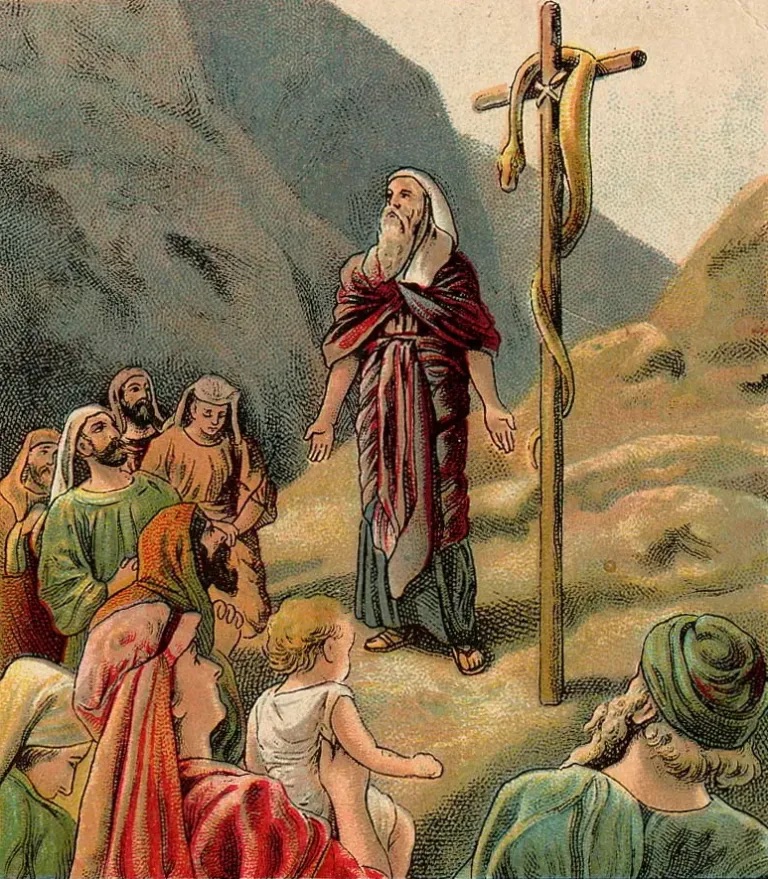

Nevertheless, there is evidence in Hebrew Scripture that “magic” was known, tolerated, even practised within Israelite society. Narrative texts purporting to tell of older stories presumably reflect the customs and practices of the time when they were compiled (perhaps during and after the Exile). Was it “magic” at Horeb, immediately after Moses was called to his role by the Lord God, when Moses threw his staff onto the ground, and it became a serpent; and then he seized its tail, and it became once more a staff (Exod 4:1–5)?

Was it “magic” at Rephidim, in a confrontation with the Amalekites, “whenever Moses held up his hand, Israel prevailed; and whenever he lowered his hand, Amalek prevailed” (Exod 17:8-13)? or in the wilderness near Moab, when Moses made a bronze serpent to heal the sick people (Num 21:4-8)? It would seem that what was a “miracle” for some would be perceived as “magic” by others.

In addition, perhaps “magic” is in evidence right within the Torah, in the provisions included in Numbers relating to “a man’s wife [who] goes astray and is unfaithful to him”. The process presumably includes a “magical” component, when the priest makes the woman drink “the water of bitterness”, made from holy water and “some of the dust that is on the floor of the tabernacle” (Num 5:16–18, 24). This seems suspiciously like a magical potion being concocted and consumed.

In later centuries, both papyri and amulets exist to attest to the presence of “magical” practices amongst Jewish people. Most of this specific evidence comes from the 3rd and 4th centuries CE, however. However, in terms of the first century, there are references to the existence of Jewish magicians in Philo, Josephus, Tobit, Jubilees, and 1 Enoch.

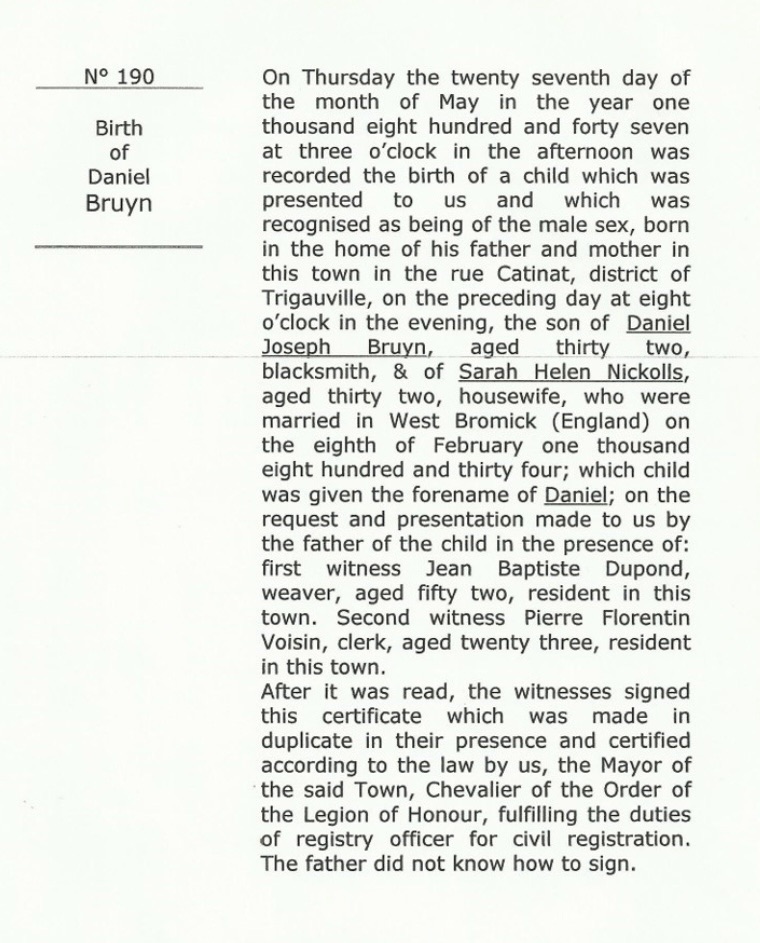

In the late 1st century CE, Flavius Josephus wrote that “God gave him [Solomon] knowledge of the art that is used against daemons, in order to heal and benefit men” (Antiquities of the Jews 8.45). Perhaps this appreciation of magic had also been also evident when “Solomon”, the alleged author of the late 1st century BCE work the Wisdom of Solomon, states that God gave him knowledge of “the powers of spirits and the thoughts of human beings, the varieties of plants and the virtues of roots”. He declares that “I learned both what is secret and what is manifest, for wisdom, the fashioner of all things, taught me” (Wisd Sol 7:21–22).

Later developments in Judaism (the Kabbalah) and on into Freemasonry envisage Solomon as not only instructed by Wisdom, but also as a practitioner of “magic”. The Key of Magic of Rabbi Solomon, for instance, is an 18th-century CE manuscript that remarkably claims to be a work by King Solomon!

In later rabbinic literature, there are many references to witchcraft. In the Sayings of the Fathers, “Hillel used to say, the more women, the more witchcraft” (Pirke Avoth 2:7). This typically patriarchal—misogynistic view is balanced, nevertheless, by the reality that the various rabbinic texts that refer to magic indicate that there were as many—if not more—men who practised this craft, than women!

In the Talmud, another sage named Abaye is said to have declared “the laws of sorcery are like the laws of Shabbat, in that there are three categories” (Sanh. 67b). (The three categories are forbidden in Torah; forbidden in the later law articulated by the rabbis; and permitted.) Indeed, in the later rabbinic period, there are two works entirely devoted to witchcraft (The Sword of Moses and The Book of Secrets). And much of the content relates to male practitioners—although these men weren’t specifically accused of witchcraft, as the women were!

For a fascinating exploration of magic in rabbinic texts, see “do you believe in magic?” by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, at https://www.lifeisasacredtext.com/witchcraft/

*****

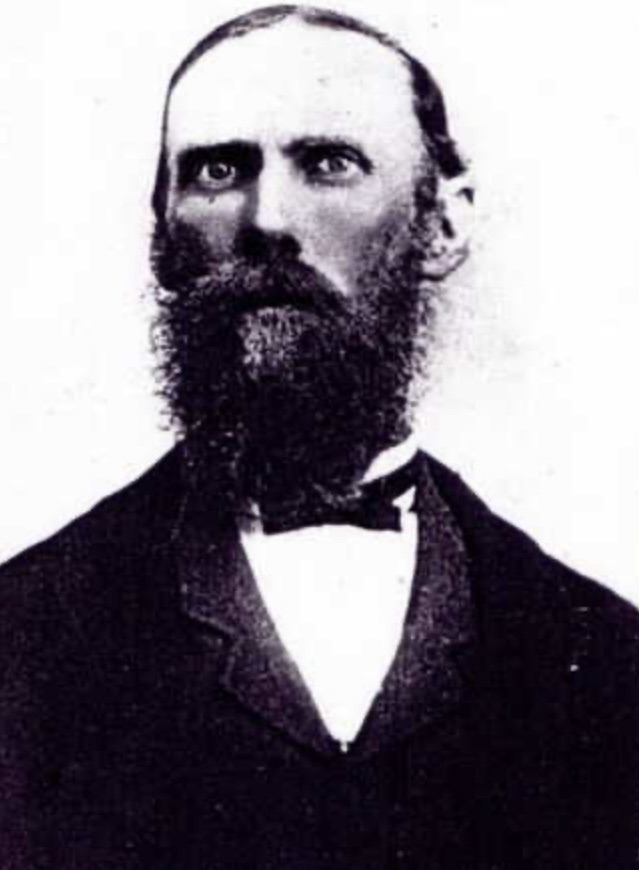

This discussion of magic and divination forms an important context for our reading of the New Testament texts that relate to magicians: Simon Magus in Samaria (Acts 8), Bar-Jesus (Elymas) on the island of Cyprus (Acts 13), and the “magicians” in Ephesus whose books were burnt (Acts 19).

Luke notes that, in a Ephesus, “God did extraordinary miracles through Paul, so that when the handkerchiefs or aprons that had touched his skin were brought to the sick, their diseases left them, and the evil spirits came out of them” (Acts 19:11). Again, what was deemed to be a miracle to those who believed, may well be seen as “magic” to others. Likewise, Paul’s resistance to the poison of the viper which attached to his arm on Malta—“he shook off the creature into the fire and suffered no harm”—results in the inhabitants declaring that “he was a god” (Acts 28:1–6). Miracle? or magic?

Finally, our understanding of “magic” might also relate to the story of the “wise ones” (magi) who “read the stars” and travelled to see the infant Jesus (Matt 2)—-and, indeed, to the “magical” elements in the healings performed by the adult Jesus of Nazareth (Mark 7, Mark 10, John 9). Was he yet another first century miracle-worker who practised “magic” like other healers?

See more on Simon of Samaria and magic at

See more on Jesus and magic at