The passage from Jeremiah proposed by the lectionary for this coming Sunday (Jer 18:1–11) is the third in a series of eight passages, taken from various sections of the work, that we read and hear during this long season “after Pentecost”. It’s a well-known passage because of the way it uses the common figure of a potter working his clay to form a vessel for domestic use. The potter spoils his work, so he starts again and works another vessel (vv.1–4).

The image of a potter is used elsewhere in Hebrew Scripture. It appears in an oracle by the prophet Isaiah (Isa 29:13–16). He poses a question to God: “You turn things upside down! Shall the potter be regarded as the clay?” (29:16). This is the very oracle whose words are used by Paul in his words to the Corinthians: “the wisdom of their wise shall perish, and the discernment of the discerning shall be hidden” (Isa 29:13; 1 Cor 1:18–19).

Paul also uses the clay element of the imagery when he later tells the Corinthians that “we have this treasure in clay jars, so that it may be made clear that this extraordinary power belongs to God and does not come from us” (2 Cor 4:7). Paul is referring to his preaching of the message about Jesus, who gives “the light of the knowledge of the glory of God” in his face (2 Cor 4:6).

We also find the potter—clay imagery used by the later unnamed prophet whose words are included in the second section of the book of Isaiah. He speaks of “the one coming from the north” who “shall trample on rulers as on mortar, as the potter treads clay” (Isa 41:21–29, see v.25). He later instructs the people not to question the intentions of God. Those who do so should remember they are “earthen vessels with the potter”; he warns them, “does the clay say to the one who fashions it, ‘What are you making’? or ‘your work has no handles’?” (45:9–13, see v.9). The image of the potter represents the sovereign power of God to act as God wishes and intends. That’s how Paul also understands it in 1 Cor 1.

In the passage offered to us for this coming Sunday, the prophet Jeremiah uses this image specifically to warn Israel that, since the people have become, in effect, “spoiled goods” because of their entrenched idolatry (Jer 18:8), the Lord God can be of a mind to discard them as unwanted. As the potter, God has unfettered freedom to mould and shape the clay exactly how he wills.

Mixing metaphors, Jeremiah then turns to the horticultural imagery employed in the opening scene of the book (“I appoint you over nations and over kingdoms, to pluck up and to pull down, to destroy and to overthrow, to build and to plant”, 1:10). So, he declares, God can decide to “pluck up and break down and destroy” the sinful nation (18:7), just as God may decide on another occasion to “build and plant” a nation (18:9).

In both instances, however, the Lord God retains the sovereign right to exercise a change of mind. If an evil nation repents, “I will change my mind about the disaster that I intended to bring on it” (18:8). Conversely, if a faithful nation, planted by God, turns to evil, “I will change my mind about the good that I had intended to do to it” (18:10). Although Christians have been taught to think of God as unchangeable, eternally the same—under the influence of the stark declaration of Heb 13:8—the testimony of Hebrew Scripture is actually that God can, and did, and will, change God’s mind.

See

So the message for Israel is clear: “I am a potter shaping evil against you and devising a plan against you”, says God; and so the plea to the people is “turn now, all of you from your evil way, and amend your ways and your doings” (18:11). The notion that God can act with evil intent is perhaps a claim that later Christian theology reacts against; after all, don’t we have the devil, Satan himself, to be responsible for all that is evil intent the world?

Yet in the world of ancient Israel, a near-contemporary of Jeremiah articulates the twofold nature of God’s sovereign actions. It comes with the territory of claiming that the Lord God is the only God—the beginnings of monotheism. “I am the Lord, and there is no other; besides me there is no god”, says the unnamed prophet of Second Isaiah. As a consequence, he reports the claim of God: “I form light and create darkness, I make weal and create woe; I the Lord do all these things” (Isa 45:5–7). There is no hiding behind Satan as the instigator of evil; for this prophet, as for Jeremiah, the Lord himself is able to act with evil intent.

Yet God does call for Israel to repent (Jer 18:11). However, their stubborn refusal to repent (18:12) leads to more recriminations from God (18:13–17), and their plotting against the prophet (18:18) leads him to plead with God (18:19–23), culminating in his strident words, “Do not forgive their iniquity, do not blot out their sin from your sight; let them be tripped up before you; deal with them while you are angry” (18:23).

The prophet’s anger matches—and perhaps even inflames—the divine wrath. So God commands the prophet to “buy a potter’s earthenware jug …. go out to the valley of the son of Hinnom at the entry of the Potsherd Gate … break the jug in the sight of those who go with you … [and declare] so will I break this people and this city, as one breaks a potter’s vessel, so that it can never be mended” (19:1–13). In this way the Lord God stands resolute against the sinful nation, who have “stiffened their necks, refusing to hear my words” (19:15). And so the scene that has begun with a command to go to the potter’s house ends with a smashed pot and wrathful words of vengeance.

On the thread of divine wrath running through scripture, see

and

A good question to ponder, though, is this: God calls Israel to repent. They need to remain faithful to the covenant. Yet Israel refuses to repent. They depart from their covenant commitment. So God acts as God has promised, to bring punishment upon them. Is this acting in an “evil” way? Or is God simply being good to God’s word?

Writing about this passage and others offered on other days this week in the daily Bible study guide, With Love to the World, the Rev. Dr Anthony Rees, Associate Professor of Old Testament in the School of Theology, Charles Sturt University, comments that “the readings this week demonstrate something of the complexity inherent in reading Jeremiah. Emerging from a chaotic, traumatic world, the texts shows the wounds of that experience, so that hope and hopelessness exist side by side. Chronology breaks down, suggestive of the challenge presented by the trauma of being unable to ‘think straight’”.

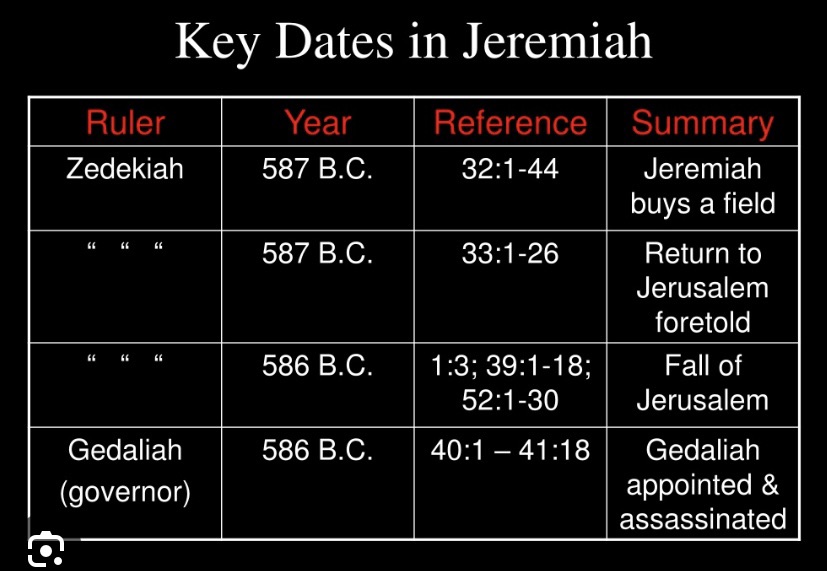

The disrupted nature of this book as a whole is well-documented. The chronological disjunctures throughout the 52 chapters can be seen when we trace the references to various kings of Judah: in order, we have Josiah in 627 BCE (Jer 1:2), jumping later to Zedekiah in 587 BCE (21:1), then back earlier to Shallum (i.e. Jehoahaz) in 609 BCE (22:11), Jehoiakim from 609 to 598 BCE (22:18), and Jeconiah in 597 BCE (22:24).

The book then returns to Zedekiah in 597 BCE (24:8), then back even earlier to Jehoiakim in April 604 BCE, “the first year of King Nebuchadrezzar of Babylon” (25:1)—and then further haphazard leaps between Zedekiah (chs. 27, 32-34, 37–38, and 51:59) and Jehoiakim (chs. 26, 35, 45) as well as the period in 587 after the fall of Jerusalem when Gedaliah was Governor (chs. 40–44). It is certainly an erratic trajectory if we plot the historical landmarks!

Rather than a straightforward chronological progression, the arrangement of the book is more topical, since oracles on the same topic are grouped together even though they may have been delivered at different times. This topical arrangement is easy to trace: 25 chapters of prophecies in poetic form about Israel, 20 chapters of narrative prose, and six chapters of prophecies against foreign nations.

Early in the opening chapters, as Jeremiah prophesies against Israel, he reports that God muses, “you have played the whore with many lovers; and would you return to me?” (3:1). The idolatry and injustices practised by the people of Israel have caused God concern. Throughout the poetry of the prophetic oracles in chapters 1—25, God cajoles, encourages, warns, and threatens the people. The passage proposed for this Sunday sits within this opening section of oracles.

There are various theories as to how the book was put together; most scholars believe that someone after the lifetime of Jeremiah has brought together material from collections that were originally separate.

Indeed, A.R. Pete Diamond concludes that “like it or not, we have no direct access to the historical figure of Jeremiah or his cultural matrix”; we have “interpretative representations rather than raw cultural transcripts”, and thus he argues that the way we read this book should be informed by insights from contemporary literary theory, and especially by reading this book alongside the book of Deuteronomy, as it offers a counterpoint to the Deuteronomic view of “the myth of Israel and its patron deity, Yahweh” (Jeremiah, pp. 544–545 in the Eerdman’s Commentary on the Bible, 2003).

So whereas Deuteronomy advocates a nationalistic God, Jeremiah conceives of an international involvement of Israel’s God. Commenting on this, Anthony Rees observes: “In this famous passage the covenant obligations which govern Judah’s relationship with God are given a broader understanding. Any nation can avoid divine punishment by turning from evil. Likewise, a nation that turns to evil stands condemned by God.”

Prof. Rees then draws an interesting conclusion. “Perhaps this relativizes Judah’s relationship with their God”, he proposes. “However, they maintain something the other nations lack: knowledge. Repeatedly God affirms that they are the only people amongst the nations who have been known by God and know God.”

In a later oracle, when God is considering to bring Israel back out of exile, into their land, he says, using familiar imagery, “I will build them up, and not tear them down; I will plant them, and not pluck them up” (Jer 24:6).

He continues, “I will give them a heart to know that I am the Lord; and they shall be my people and I will be their God, for they shall return to me with their whole heart” (24:7). This is the fruit of knowledge: to be completely faithful to the Lord God.

And then, in yet another oracle—and this one so well-known because of how it is used in the New Testament—the prophet reports God’s intention to make “a new covenant” and to “put my law within them and … write it on their heart”. In this situation, “no longer shall they teach one another, or say to each other, ‘Know the Lord’, for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest” (Jer 31:31–34). This knowledge is at the heart of the covenant. As the psalmist sings, “this I know, that God is for me” (Ps 56:9b). Or, as the Sunday school song goes, “Jesus loves me, this I know”.

So Prof. Rees concludes: “This is the great tragedy of [Israel’s] failure, and our own, that we know, and yet still follow our own plans that run contrary to the desires of God. Still, here we have the prophetic call to turn, to amend our ways and to live into that which, and whom, we know.” It is a call that stands, still, in our own time. How do we respond?