Today, 31 October, begins a special sequence of days, which in traditional Roman Catholic piety form a triduum (simply meaning, “three days”). There is one set of three days that is very well-known: the Great Three Days of Easter (Good Friday—Holy Saturday—Easter Sunday). This current sequence of three days is the “other” three days—standing in the shadow of those other three days. Whilst the three days of Easter celebrate new life (the Triduum of Life), this “other” set of three days has been called the Triduum of Death.

Why, death? Well, the explanation lies in the three particular days that are included: All Hallows’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls’ Day. All three have to do with life beyond this life as we know it, in one form or another—that is, they are dealing with death and those who have died.

All Hallows’ Eve is best known to us as Halloween; it falls, every year, on 31 October, round about six months after Easter Sunday. Unlike Easter, however, this is not a “moveable feast”, following the pattern of the lunar cycle (which does not lineup with our solar-based calendar). Halloween falls, each and every year, on the very last day of October.

It needs to be said that the contemporary commercialised celebration of Halloween is a long way from its origins in medieval Christian piety. And so it also needs to be emphasised that Halloween is not a pagan festival. It has its origins deep in Christian history and tradition.

The English word ‘Halloween’ is a shortening of All Hallows’ Eve(n), which long ago began this series of three holy days, designed to enable the faithful to remember the saints of old (All Saints’ Day on 1 November) and the faithful who have died, “the souls of the faithful departed” (All Souls’ Day on 2 November). These three days, Halloween—All Saints’ Day—All Souls’ Day, belong together—as the “other” Christian triduum (like Good Friday—Holy Saturday—Easter Sunday).

How long ago this sequence began is not clear, as local customs varied. There is evidence that some days had been identified as the time to remember individual saints or groups of saints in some locations in the 7th to 9th centuries. By around 800, churches in Northumbria and Ireland apparently remembered “all saints” on 1 November.

In the online resources of the Northumbria Community, there is a good statement about the significance of this time: “The old belief was that there was danger and vulnerability at this time of transition, which was neither in one year nor the next. Spiritual barriers could be dissolved. Inevitably, looking back led to the remembrance of those who had died and gone before; and, as the dark, cold days were awaited, protection was sought against the evil spirits that were bound to be abroad until spring returned. These old beliefs were never quite eradicated by the coming of Christianity, but lingered as a persistent superstition, a residual folk memory.” See

https://www.northumbriacommunity.org/saints/celtic-new-year-all-hallows-eve-and-all-saints-tide-october-31stnovember-1st/

By the 12th century, All Saints’ and All Souls’ had become holy days of obligation in the medieval churches, and various rituals developed for each day. Baking and sharing cakes for the souls of baptised people is evidenced in some European countries in the 15th century; this may be the origins of trick-or-treat. Lighting candles in homes on these days was done in Ireland in the 19th century—another element which is reflected in current Halloween practices.

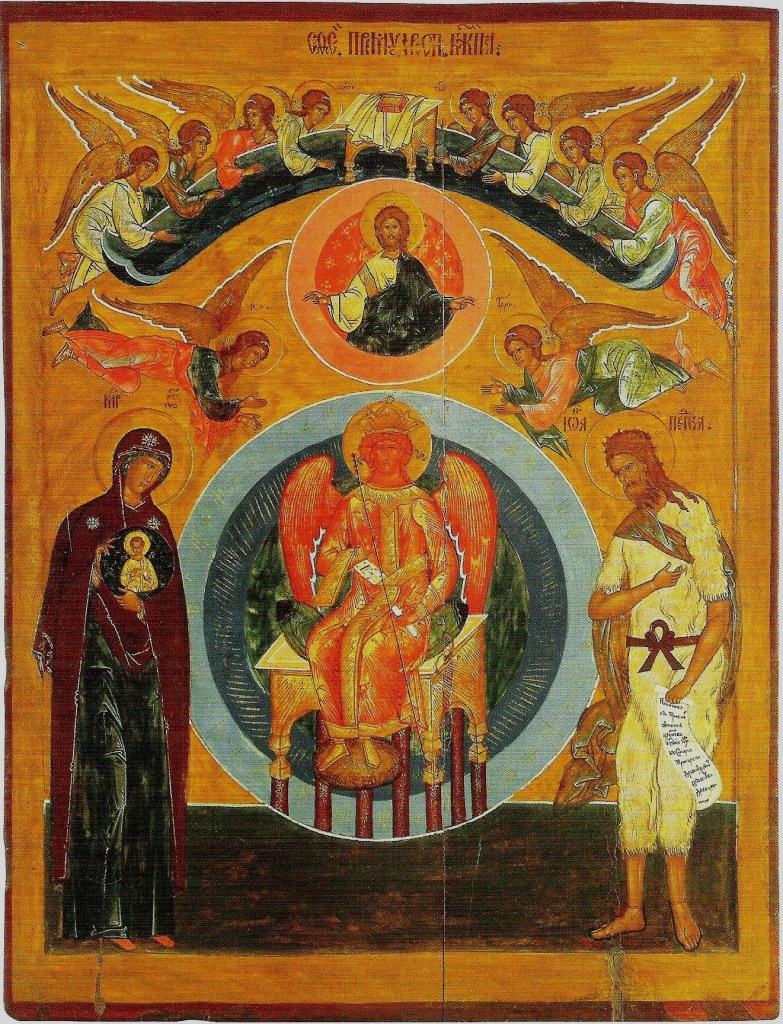

by Fra Angelico (1395–1455)

I have had the experience, in churches today, of being caught up in a grand worship experience for All Saints’ Day, the middle of the three days (a number of these were memorable experiences where my wife Elizabeth Raine created and presided at the liturgy). We surrounded ourselves with the memory of saints of ancient and more recent times, and recalled with gratitude saints of the present times, particularly those important to the immediate locality or congregation.

In those times of worship, we joined in singing “for all the saints who from their labour rest—alleluia! alleluia!” (from a hymn by William Walsham How), and then “a world without saints forgets how to praise; in loving, in living, they prove it is true— their way of self-giving, Lord, leads us to you” (from a hymn by Jacob Friedrich).

It is sometimes claimed that Halloween originated as a response to existing pagan rituals—but we need some considered nuance as we reflect on this. A number of the current practices involved in Halloween certainly do show the strong influence of folk customs with pagan origins in a number of Celtic countries.

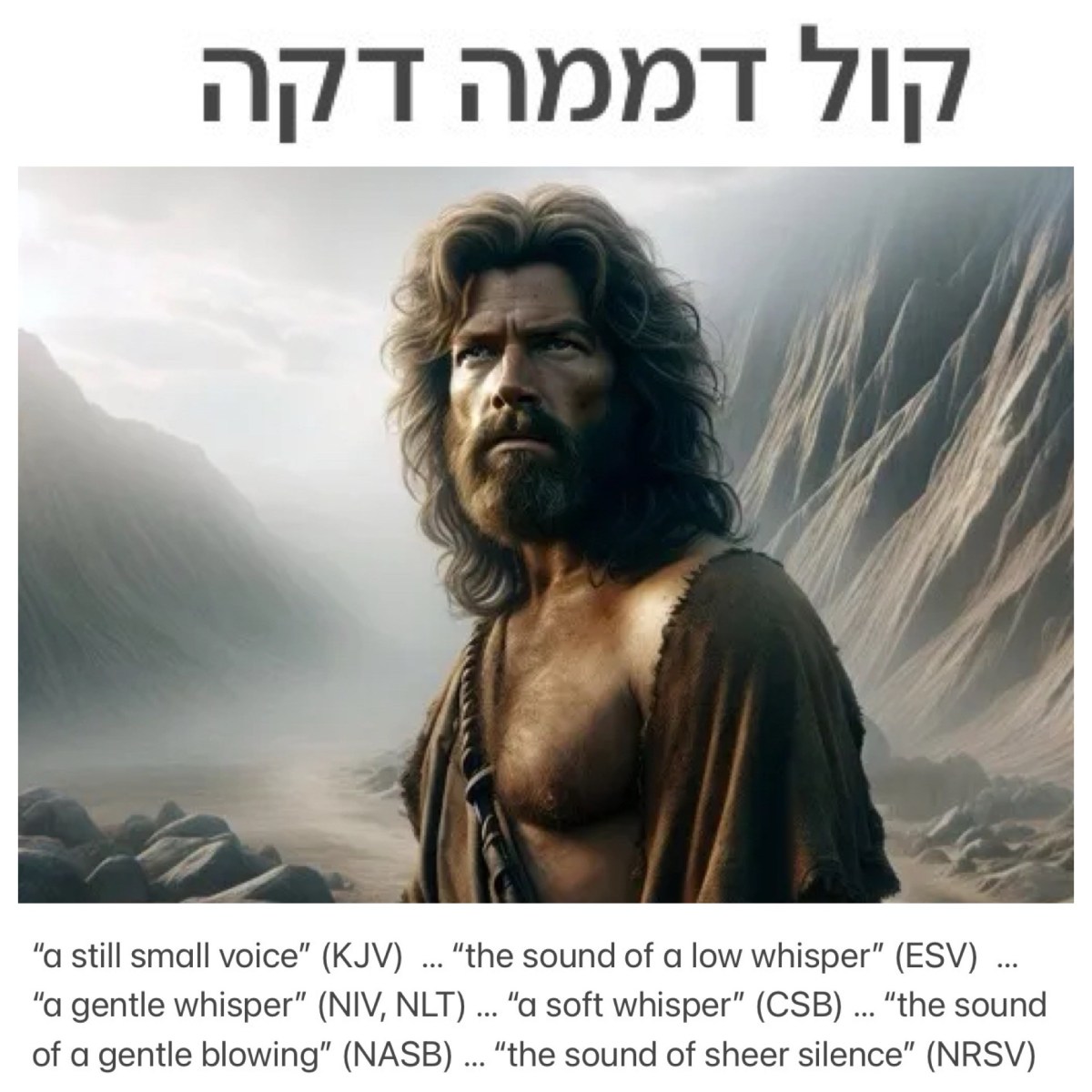

This is especially so in relation to Samhain in Ireland, marking the start of winter with a festival from sundown on 31 October to sundown on 1 November. This was a liminal time when the boundary between this world and the world beyond was thinned; at this time, it was thought, the spirits could more easily enter this world. The connection with the Christian days of All Saints’ and All Souls’ is thus clear to see.

However, this does not mean that we can simply (and simplistically) conclude that these days have pagan origins; rather, what we ought to recognise is that, like other Christian festivals, there has been a blurring of customs and practices and a linking of Christian patterns with pagan festivities.

This blurring and linking is a natural tendency that has taken place time after time in place after place. This is what historians and scholars of religion call syncretism—the merging and assimilating of traditions that were originally discrete, with separate origins. It can also be called eclecticism; but I prefer to see this more accurately as contextualisation, the shaping of a tradition in the light of the immediate social and cultural context.

For that is what Halloween did in the mists of the time when it was being created and shaped—existing practices of pagan neighbours were co-opted and adapted by faithful Christians. Then, the practices were extended with the introduction of days to remember All Saints and All Souls. (The same dynamic was at work in the ways that Easter was shaped, drawing on northern hemisphere Spring practices, and the way that Christmas also developed, drawing on northern hemisphere Winter Solstice practices—but these are stories for other times of the year!)

The same perspective can be applied to the ways that Halloween, in particular, is commemorated each year. Lamenting the commercialisation of a festival that was originally Christian is a poor strategy. (And, as noted, this commercialisation has already happened with Christmas—which is now peak selling period for so many businesses and peak holiday period for many families—and in a different way with Easter—which is now a second peak holiday period for so many families.)

This kind of commercialisation (Jack-o’-Lantern pumpkins, bright lanterns, all manner of costumes, the proliferation of sweets for Halloween, trick-or-treat, and more) is now well underway with Halloween. We won’t turn the clock back. People of faith can simply hold to Christian understandings and practices in the midst of the increasing changes being made in broader society. As we observe what is taking place around us, the best strategy, surely, is to inform ourselves of the origins of, and reasons for, the season, and to reflect on those matters that take us to the heart of our faith.

*****

To close, here is my poetic musing on this season in the life of the church:

Every year in the church we remember,

we remember the saints of old;

those who kept silence, those who spoke clearly,

monks and ascetics, sisters and nurses,

teachers and preachers, writers and poets,

mystics and prophets, all serving faithfully;

saints who were blessed in their lives,

saints who blessed others through their lives.

Every year in the church we remember,

we remember those souls now departed;

family, friends, acquaintances, strangers,

known and remembered, hallowed in death.

To commemorate all the faithful departed,

we mark this time as All Souls’ Day.

And the evening before All Saints’ Day,

it is best known as “Halloween”.

Hallowed, sanctified, sainted in memory,

recalled in remembrance, all saints and all souls.

Once in each year, that is our focus;

once in each year, year after year.