Some weeks ago, the Narrative Lectionary offered the story of God calling Moses to lead his people out of slavery, into freedom (Exod 3–4), followed by another story about the way that Moses exercised this leadership during a testing time (Exod 16). Two weeks ago, we heard the story of God calling Samuel to be prophet (1 Sam 3)—the first of many who would be called to that role. Then last week, we moved on to hear the story of God calling David to be king. So we have had stories about a range of leaders in ancient Israel: the Liberator, the first Prophet, and the most beloved King.

This coming Sunday we jump to another element that is foundational in the religion of ancient Israelite society. For many years—ever since the “wandering in the wilderness”—the people had a focal point for worshipping their God. The Tabernacle, created during the “wilderness story”, was a mobile sanctuary, travelling with the people (Exod 25:1–9). This sanctuary was faithfully served by the Levites, a group set apart for this priestly role (Num 1:48–54).

However, the central figure in this coming Sunday’s story is not a Priest, but rather a King—Solomon, one of the many offspring of David, and the one who, by all manner of machinations, succeeded his father on the throne. The lectionary deftly steps over all those stories, told with gruesome detail in the early chapters of 1 Kings.

Solomon was not first in line to ascend the throne; that would lie with the eldest of his brothers still living, Adonijah. Adonijah knows this; the first book of Kings opens with the revelation that, since “David was old and advanced in years … Adonijah son of Haggith exalted himself, saying, ‘I will be king’; he prepared for himself chariots and horsemen, and fifty men to run before him” (1 Ki 1:1,5).

However, Solomon plots with his mother Bathsheba and the palace prophet Nathan to arrange for the assassination of his older brother. In addition, a number of other people also had to be eliminated to establish Solomon’s firm grip on the monarchy, and to ensure there were no other possible legitimate claimants to the throne remaining. Such was the raw and vicious nature of “life at the top” those days. (Has anything much changed?)

In fairly quick succession, after Solomon had arranged for the death of his eldest brother Adonijah (2:13–25), he banished the high priest Abiathar who had supported Adonijah (2:26–27) and replaced him with another priest loyal to himself. Next he removed Joab, a cousin who was the commander in the former king’s army (2:28–34). He achieved this via a hit man, Benaniah, who became the general of his army (2:35).

Then, Solomon had Shimei, who was a relative of Saul, the king before David, killed (2:36–46). In this way all potential contenders for the throne and their powerful supporters were removed, mostly by violent means. As the narrator curtly comments, “so the kingdom was established in the hand of Solomon” (2:46b).

Fortunately for preachers following this lectionary, there is no expectation that there will be any need to read, reflect on, and speak about these chapters during worship. They certainly reveal the depths of degraded humanity! Rather, in the manner that characterises the Narrative Lectionary, we move from high point to high point—and so, this coming Sunday (in 1 Ki 5:1–5), we hear about the beginning steps taken by Solomon in the preparations for erecting the building which would not only sit on the highest point in Jerusalem, but would stand as a symbolic representation of the highest elements—what was best, most valued, most important—in ancient Israelite society.

Solomon, King of Israel, consults with Hiram, King of Tyre (who has a large navy and workforce) regarding the materials and labour needed to undertake this major building project (1 Sam 5); as the narrator indicates, “Solomon’s builders and Hiram’s builders and the Gebalites did the stonecutting and prepared the timber and the stone to build the house” (1 Ki 5:18). And then, after seven years of intense work, the temple is complete (7:1). Here, the lectionary (wisely) skips over the tedious detail of the items made by the artisans and craftsmen of Solomon (6:1–38).

The second part of the reading offered by the lectionary for this coming Sunday tells of how, after thirteen years, King Solomon assembled “the elders of Israel and all the heads of the tribes, the leaders of the ancestral houses of the Israelites” (8:1). Again, the lectionary skips over the detailed account of the work of Solomon’s men in building his own house: the House of the Forest of Lebanon, the Hall of Pillars, the Hall of the Throne, and the house where he would live (7:1–12).

In like manner, the lectionary jumps over the detailed account of the work of Hiram the bronze worker: pillars, stands, basins, pots, and a whole host of items to be used in the sanctuary (7:13–50). Thank goodness the lectionary compilers jumped over all of those verses!

At any rate, when Solomon assembles the leaders of the nation, in the presence of “all the people of Israel” who had assembled, the priests and Levites bring forward the Ark of the Covenant, the Tent of Meeting which had housed the Ark for decades, and “all the holy vessels that were in the tent (8:1–4). It was surely an impressive majestic procession, followed by a scene of overflowing abundance, as the priests received and sacrificed “so many sheep and oxen that they could not be counted or numbered” (8:5).

There’s no mention of the rivers of blood that must surely have flowed as these sacrifices took place. It may seem like a most unpleasant and unedifying scene to modern eyes and ears; however, the sacrificing of blood was an expression of the central Israelite belief that “the life of the flesh is in the blood … as life, it is the blood that makes atonement” (Lev 17:11). Each sacrifice of a chosen animal was a sacred offering of life that symbolised the obedience and dedication of the person, or people, who had brought the animal to be sacrificed. They were dedicating their whole life to the Lord God through this action, and in return, they were receiving atonement (the forgiveness of their sins) for all the misdeeds they had performed.

Finally, after the procession and sacrifices, the Ark was brought to “the most holy place” (8:6). The presence of the Ark evoked Solomon’s father, David, and his taking of the city from the Jebusites. Solomon was making clear that he was seen to be standing in that fine tradition.

The Ark was placed in the space known as “the Holy of Holies”, as a much later Jewish-Christian writer describes it (Heb 9:3). It was from that time to be set apart as holy for only the High Priest to enter, and at that but once a year (Heb 9:7).

The scene is presented as one of profound religious significance, for “when the priests came out of the holy place, a cloud filled the house of the Lord, so that the priests could not stand to minister because of the cloud; for the glory of the Lord filled the house of the Lord” (1 Ki 8:10–11). The Temple from that time became the fixed dwelling place of God; “O Lord, I love the house in which you dwell, and the place where your glory abides”, one psalmist sings (Ps 26:8); another sings, “bring an offering, and come into his courts; worship the Lord in holy splendour; tremble before him, all the earth” (Ps 96:8b-9). Other psalmists likewise assert the holiness of God in his temple (Ps 11:4; 24:3–4; 48:1; 99:1–5,9).

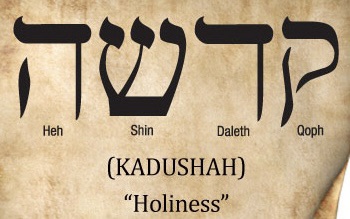

Holiness (kadushah) was central to the people of Israel. Those who ministered to God within the Temple, as priests, were to be especially concerned about holiness in their daily life and their regular activities in the Temple (Exod 28–29; Lev 8–9). The priests oversaw the implementation of the Holiness Code, a large section of Leviticus (chapters 17–26), which explained the various applications of the word to Israel, that “you shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy” (Lev 19:2; also 20:7,26). The people were expected to be a holy people, dedicated to God, serving obediently by adhering to all the laws and commandments that Moses had received from the Lord God at Sinai (Exod 19:5–6).

As the glory of the Lord fills the Temple, Solomon makes the solemn declaration to his God that “I have built you an exalted house, a place for you to dwell in forever” (1 Ki 8:13). He then offers an extended prayer which stretches over the next 38 verses—another element of the whole story that the Narrative Lectionary, mercifully, does not prescribe for reading in worship!

Henry J. Soulen, ‘Queen of Sheba Visits Solomon’ (1967), illustration in Everyday Life in Bible Times

(National Geographic Society, 1967), pp. 230-231

Solomon, I am sure you are thinking, is remembered as The Wise King. As the lectionary has offered this passage for this Sunday, it is worth our thinking further about Solomon. Next week we will jump forward a century or so, to the prophet Elijah. So we might, today, reflect on the quality of Solomon he is best known for: his wisdom. In 2 Chronicles 1, God says to Solomon, “because you have asked for wisdom and knowledge for yourself … wisdom and knowledge are granted to you” (2 Chr 1:11).

And later, King Solomon is said to have “excelled all the kings of the earth in riches and in wisdom. And all the kings of the earth sought the presence of Solomon to hear his wisdom, which God had put into his mind. Every one of [those kings] brought silver and gold, so much, year by year” (2 Chron 9:22–24). And so, Jesus relates how “the Queen of the south [the Queen of Sheba] came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon” (Matt 12:42).

This wonderfully wise, insightful, discerning man, Solomon—bearing a name derived from the Hebrew for peace, “shalom”—became a powerhouse in the ancient world. But he did not always live as a man of peace, as we have seen in tracing his rise to the throne. Indeed, as ruler he used his 4,000 horses and chariots and 12,000 horsemen to good effect; we read that “he ruled over all the kings from the Euphrates to the land of the Philistines and to the border of Egypt” (2 Chron 9:26).

Solomon was remembered as king over the greatest expanse of land claimed by Israel in all of history. This large scope of territory noted in scripture forms the basis for the claims of zealous fundamentalist Zionists, in the 21st century, that Israel should run “from the river to the sea”. It’s a claim that has fuelled the building of illegal Jewish settlements on the West Bank and the erection by the modern state of Israel of The Wall which divides Israel from Palestinian Territories—but which divides families and friends as it seeks to separate Israelis from Palestinians.

Solomon, there can be no doubt, was a warrior. And warrior-kings were powerful, tyrannical in their exercise of power, ruthless in the way that they disposed of rivals for the throne and enemies on the battlefield alike. Think Alexander the Great. Think Charlemagne. Think Genghis Khan. Think William the Conqueror. Solomon reigned for 40 years—a long, wealthy, successful time. (Although 40 years, in Israelite time, is basically a way of saying “a heaps long time”.)

Yet in the passage we hear this Sunday Solomon appears not as a powerful king. Rather, he is a humble person of faith. He stands before all the people, raises his arms, and prays to the God who is to be worshipped in the Temple that he had erected. He is a person of faith, in the presence of his God, expressing his faith, exuding his piety.

The prayer of Solomon goes for thirty-eight solid verses; there are eight different sections in this prayer. In the first two sections of this prayer, Solomon identifies two important features of the newly-erected Temple. The first is that the fundamental reason for erecting this building is to provide a focal point, where people of faith can gather to pray to God (2 Ki 8:23–30). The second key element of Solomon’s prayer is that the Temple reaches beyond the people of Israel, covenant partners with the Lord God. He recognises that the Temple is also the place for the prayer of “a foreigner, who is not of your people Israel, [who] comes from a distant land because of your name” (2 Ki 8:41–43).

This is a striking and dramatic element to include in this dedication prayer before all the people of Israel! Perhaps that is the best way we can remember Solomon: a man of his time, committed to his people, but open to receiving the gifts and the prayers of people from afar. Would that, in our present world of nationalistic fervour, militaristic aggression, and parochial bigotry, there were more rulers like that!

For more on the prayer of Solomon in 1 Kings 8, see