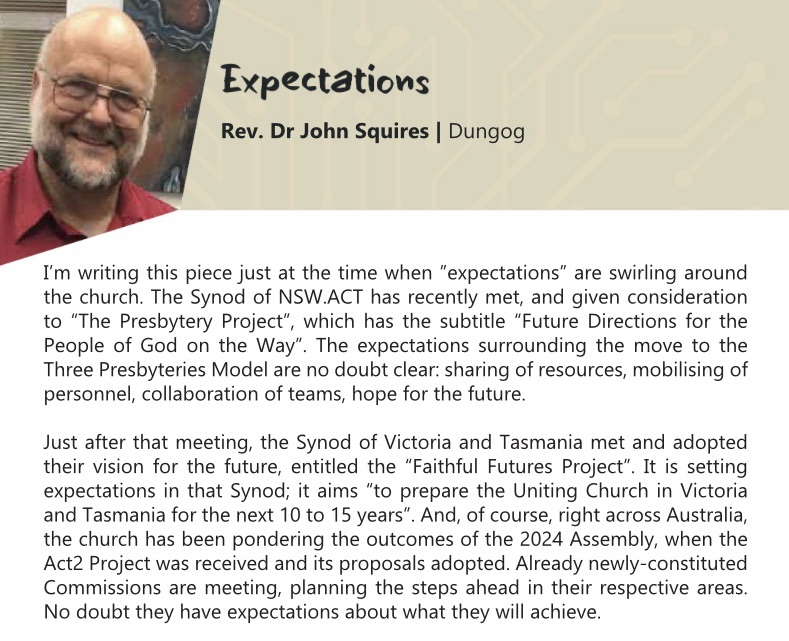

A sermon on Isaiah 7:10–16 and Matthew 1:18–25, for the fourth Sunday in Advent, preached by the Rev. Elizabeth Raine at Dungog Uniting Church on 21 December 2025.

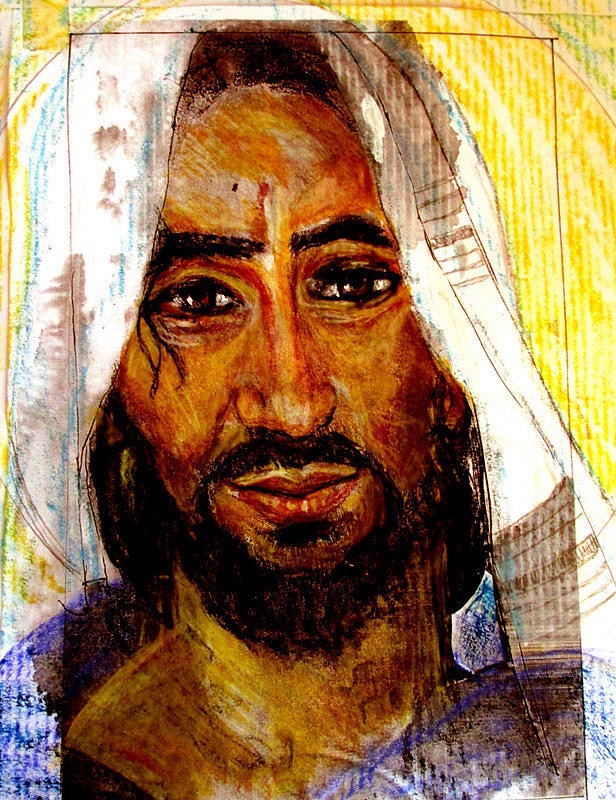

The gospel of Luke so dominates the Christmas season that only occasionally are we afforded an opportunity to experience the birth of Christ from a perspective other than Luke’s. So I am quite happy that here on the last Sunday of Advent, we are given a chance to hear the story from a different perspective, that of Joseph, the husband of Mary. As we might expect, Mary is not the only one shocked by the announcement that she is pregnant. Now it is Joseph’s turn to listen to the angel, and have his faith tested as to what is deemed “righteous”.

All of us dream. But when should we pay attention to our dreams? When are our dreams truthful and when are they simply ridiculous? Are dreams always the product of our own malformed desires or can they contain a truth or a warning that must be heeded? When we fall through our conscious mind’s trapdoor into the wider consciousness of our unconscious mind, what is revealed? Can it really help us to head in the right direction?

How did Joseph know to turn aside from righteousness as he knew it, to follow a non-rational, alternative righteousness from the darkness of his unconscious dreams? For Joseph, the Greek word dikaiosoune referred to a “righteousness” that would have included obeying the law. The law meant that a woman in Mary’s predicament—pregnant but unmarried—could well have been at risk of being stoned to death.

Something in his life, perhaps a yearning to use love rather than the stringent expectations of his society as a guide, must have prepared Joseph to pay attention to that particular dream that night: do not fear to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.

See the discussion by the Rev. Cynthia Taylor at

https://www.augustachronicle.com/story/lifestyle/columns/2019/12/23/cynthia-taylor-nontraditional-nativity-scene-shows-reality-of-birth/2021252007/

Such a statement could no doubt make perfect sense in the context of a dream. But what happens when Joseph wakes up and the real world, complete with scandal, reputation and rules comes flooding in with the light of day? What is the more likely scenario that Joseph faces: that Mary experienced sexual relations (welcome or unwelcome) or that she is pregnant by the Holy Spirit?

But the angel in the dream links the message with a scripture passage familiar to Joseph, the dreamer: “Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him ‘Emmanuel’, which means, “God is with us”.

As a poor man working as an artisan (probably building for the Roman oppressors), Joseph drew hope from these texts, this promise, this dream of all dreams. What righteous dreamer upon waking would not lay down his prejudices for such a dream?

Joseph, like his ancestor Joseph the son of Jacob, appears to have trusted his dreams. But even more than his dreams, in order to embrace Mary’s unusual pregnancy Joseph must have also trusted the voice of God in the prophets, which speak of justice rather law, and tell narrative tales of reversals of power, where in an unjust society where things are frequently turned upside down.

We will turn now to Isaiah, where the angel’s message comes from. When Israel and Syria demanded that Ahaz align with them in an attempt to overthrow the growing power of Assyria, Ahaz was frightened and undecided. On the one hand they threatened to invade Judah if he should refuse, and so the safer option seemed to be to join them. But, on the other hand, there was a possibility that asking Assyria for protection against the two smaller powers would be even safer.

Yet, Isaiah advised the king against these very human solutions, and challenged him to trust God that the threatened invasion would not happen. He even offered Ahaz the opportunity to ask for a sign, which Ahaz, feigning piety, declined. In frustration, then, Isaiah gave Ahaz a sign anyway, but it was extremely enigmatic, and seems not to have convinced Ahaz at all.

The sign Isaiah offered was that “the young woman” (the Hebrew does not say virgin – that word was introduced by the Septuagint), who was almost certainly known by the prophet (hence the definite article), would become pregnant and would give birth to a son who would be named Immanuel (God is with us). By the time this child was weaned and old enough to reject evil and choose good, the threat would be gone.

The problem with this sign is that Ahaz was being asked to exercise faith before the sign could be proved true. He would have to choose to trust Isaiah’s word, and then wait and see if the sign would indeed be fulfilled as Isaiah predicted. It’s a powerful sign, but not much use if it is intended to bolster faith before the fact. The result is that Ahaz, it seems, was unconvinced. He joined forces with Assyria, with disastrous consequences in the end for Judah.

Nevertheless, the sign Isaiah offered was significant for a number of reasons. The name of the child was ambiguous in the sense that God’s presence, especially in those traumatic times, could be seen as both good news – God would rescue the faithful – and as bad news – God’s presence would bring judgment on faithlessness. This sense of God’s presence being both a comfort and a confrontation is a constant theme in the Scriptures, and one that is often lost in Christian proclamation (especially in the Christmas season), or twisted into a caricature of itself in “hellfire-and-damnation” preaching.

But, the other significant feature of this sign is its character. This is no dramatic, supernatural event that the prophet promises. Nor is it a destructive attack on Judah’s enemies. Rather, the sign that is given is natural — childbirth happens all the time — and creative — in childbirth, a new life is created. God’s presence, says Isaiah, is known in the natural ordinary rhythms of life, and through the creativity that brings new life into the world. Where the powers of the day were threatening destruction and death, God called Ahaz to trust in the greater, creative power of life. However, Ahaz believed more strongly in death, and so he made choices that brought death and destruction on his nation.

Years later, as the writer of the Gospel of Matthew sought to describe God’s intervention to a people who had witnessed the worst that the destructive Roman Empire could do, and who were being threatened with death and destruction for simply professing faith in Jesus, he recalled Isaiah’s sign to Ahaz. Using the Septuagint’s word “virgin”, he spoke of Jesus’ birth as a sign of God’s salvation, and an assurance of God’s presence.

For a people who must have been tempted either to give up on their faith and align themselves with the seemingly indestructible Empire that threatened them, or align with the small groups of rebels who continued to try and undermine the Empire’s power, the context of Isaiah’s sign to Ahaz must have resonated strongly.

Indeed, Matthew’s intended use of the sign would have been to communicate the same message as Isaiah — God’s presence was with God’s people (to save or confront, depending on their willingness to trust in God’s salvation) and God’s creative, life-giving activity was stronger than the forces of death and destruction.

By using this sign as the start of his account of Jesus’ life and ministry, the Gospel writer established at the outset that Jesus’ agenda was not to engage the world’s powers in violent conflict, or divine shows of dominance.

On the contrary, Jesus’ work was to lead people into an experience of God’s creative life that would sustain them, empower them to resist the temptation to seek solutions and security through armaments and violence, and enable them to become an alternative community that would serve and support one another and their neighbours through acts of creative love, service, compassion, and mutual care — through building God’s dream of shalom.

As we stand at the threshold of another Christmas, the Advent journey asks us, once again, how we will understand this season and the One around whom it revolves. When we speak of peace – shalom – on earth and goodwill to human beings, how exactly do we expect this to come about? Do we wish to turn Jesus into a super hero who swoops in and fixes everything for us? Do we insist on seeing Jesus as an alternative military conqueror who destroys his (which equals our) enemies? Or can we see the signs of God’s Reign as they are offered to us, embracing their call to faith even when they have not yet come to fruition?

In the dark days of apartheid in South Africa, it was forbidden for white people to enter black townships without a government-issued permit. This made it incredibly difficult for followers of Christ to worship together across racial boundaries. Black people often did not have access to the transport they needed to get into the suburbs over weekends, and even if they did, they always ran the risk of being stopped and harassed by security forces.

White people, for the most part, would not risk entering a township without a permit, and, since they usually had little need for one, they would never set foot in a township church. The result was a division in worship that mirrored the racial and economic divisions of the nation.

Yet, in small pockets around the country, believers from across the racial spectrum found ways to meet and worship together. Although this could result in accusations of gathering illegally and possibly arrest, they nevertheless risked the consequences because they believed that the Gospel required it of them. As they called for an end to the oppressive system, they began to live, in small, peaceful worship meetings, another reality. They believed that justice would prevail, and that they needed to begin to act as they would if apartheid did not exist.

Long before their first democratic election, these courageous South Africans lived as a sign of what the country could become, and in doing so, they helped to create for all what they practiced in their small groups. There was no guarantee that they would find a peaceful way to come together, but these courageous “sign-people” gave hope that it could be done.

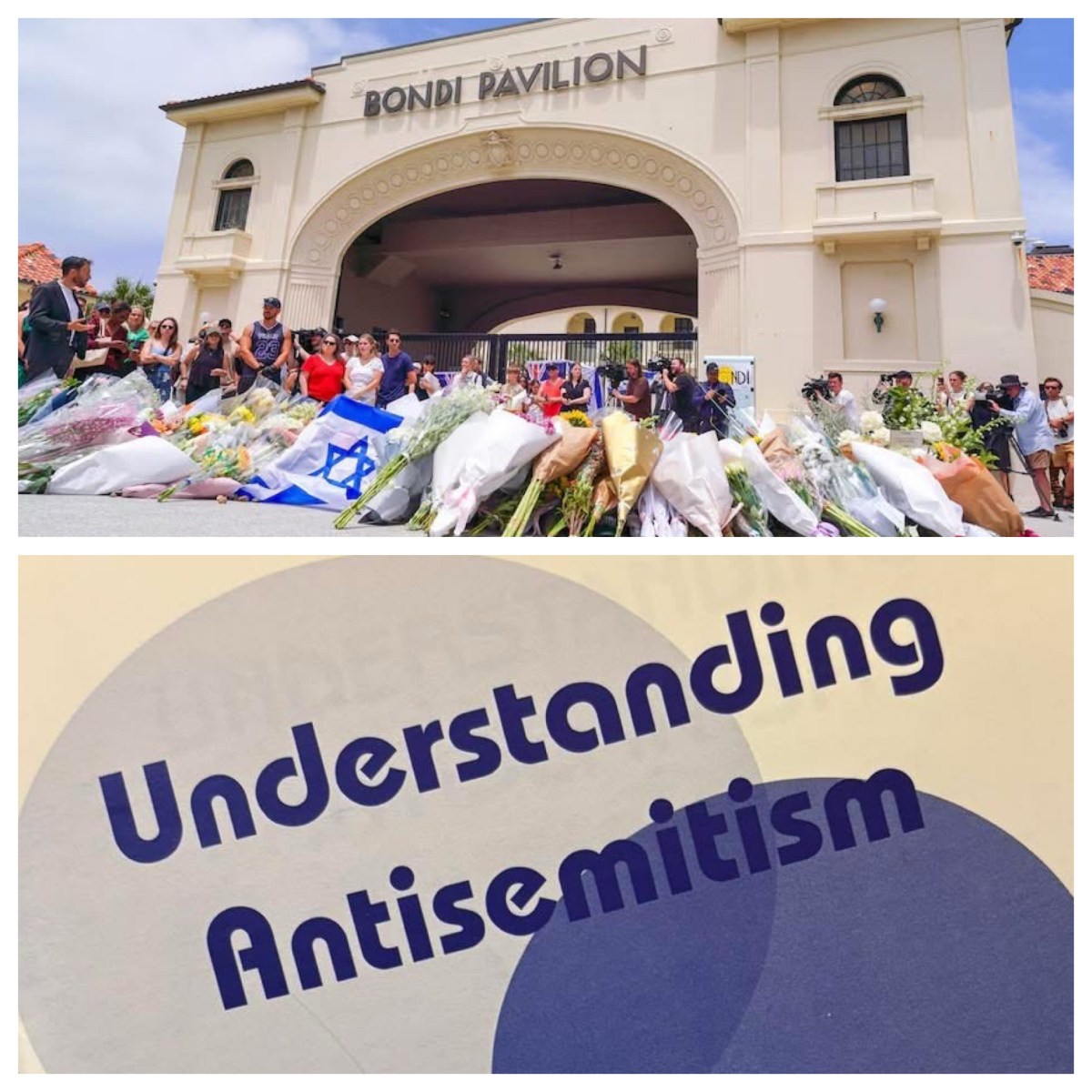

The recent tragedy at Bondi Beach is another such example of hope. Whilst the event itself was shocking, and driven by fanatical ideology, from the catastrophic events arose a phoenix of hope, with many heroes tackling gunmen, sheltering others, and running right into the fray to help when every fright, flight and fight instinct probably called for flight. These heroes came from different faiths and different walks of life, but put others before themselves by their self sacrificing actions. In the aftermath, people came together to mourn those who died and show unity, not hatred, in their grief and distress. They showed that in a very broken world, there are always signs of hope.

The nativity too is a sign of hope in a broken and troubled world. Like Joseph, who decided that love was a greater righteousness than law, and who trusted his dream enough to marry Mary and raise the child in spite of the potential social consequences, we too are called to act in trust, and embrace the creative life of God, no matter the consequence. The world is not yet filled with peace and goodwill.

The Reign of God remains hidden and seemingly impotent against the forces of violent power, extravagant wealth and corporate & political corruption in our world. Yet, if we can find the courage, like Joseph in the story, to live out God’s dream for us in small, determined daily actions of creativity and life-sharing, we will know God’s presence is with us, and we will see the dream’s fulfilment in our hearts, even as we wait for its fulfilment in our world.

Let us not lose heart. Let us never fall into believing that the death and destruction we see around us have the final word. Let us pray for the courage and the faith to be captured by God’s dream of shalom and to seek to live it out — for our own sakes, and for the sake of our world — no matter how hard it may be.

Give us your dream, O Holy One. Guide us and give us courage, like Joseph, to live toward your dream’s fulfillment. Amen.