A celebratory service of worship was held on Sunday 8 March in the Carrington Ave Uniting Church in Strathfield, to recognise that With Love to the World (WLW) has been in existence for 50 years. It is a unique Australian resource—written and produced by people within the Uniting Church in Australia, for people of faith in Australia and surrounding countries. It reflects a “southern hemisphere” take on matters of faith and life.

The first issue of WLW was printed in March 1976. It was written by Bob Maddox and Gordon Dicker, two lecturers at Leigh College, Enfield, the Methodist Church theological college, then printed, collated, and distributed by volunteers from seven local churches in the Strathfield—Homebush area.

The college soon became part of United Theological College, while the seven churches (Methodist, Congregational, and Presbyterian) formed the Strathfield—Homebush Parish of the Uniting Church in 1977. Since then, WLW has been operated by a partnership of UTC and the Strathfield—Homebush UCA, under the auspices of the Synod of NSW.ACT.

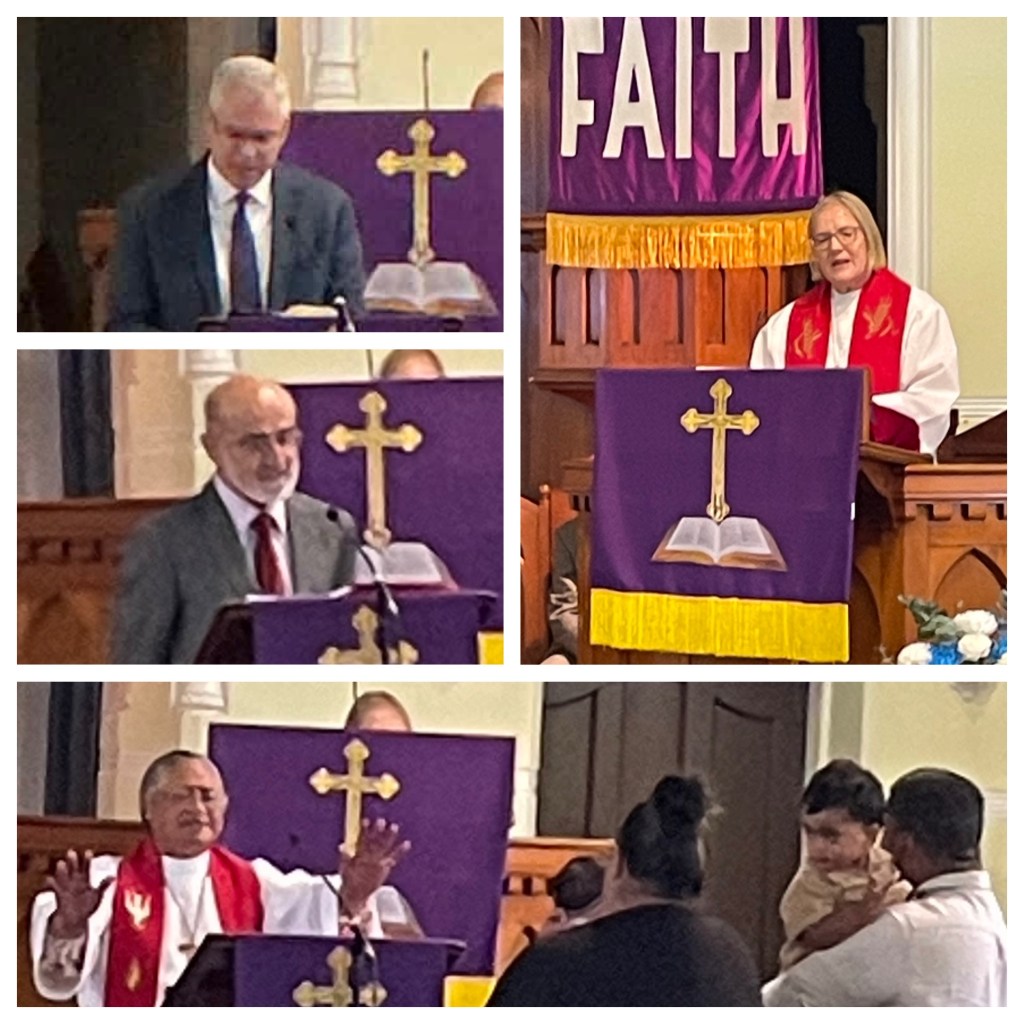

The service of worship was conducted by the Rev. Fololeni Tafokitau, minister of the Strathfield—Homebush Uniting Church. After an Acknowledgement of Country, a Welcome was given by William Emilsen, who reminded those present of the twofold purpose of WLW: (i) to produce a high quality and accessible commentary on the lectionary passages for the coming Sunday; and (ii) to support the research and writing of Uniting Church postgraduate students. It has done the former since 1976, and the latter since the first scholarship was granted in 1982. Since then, 65 people have received scholarship support.

The congregation then joined in a responsive version of Psalm 95, adapted for the occasion, and joyfully sang the Doxology. Music remained a feature of the service as people sang a number of favourite hymns, and the Tongan Choir led in a characteristically rich presentation of a song highlighting the importance of our scriptures.

Words from scripture were read by Seneti Katoa (Secretary of the WLW Committee) and the Rev. Dr Peter Walker (Secretary of the Synod of NSW.ACT). Peter had, until recently, been the Principal of United Theological College; the two readers represent the two bodies who have been in partnership since the beginning of WLW in 1976.

On the right: Vicky Balabanski.

The guest preacher for this occasion was the Rev. Professor Vicky Balabanski, Principal of the Uniting College of Leadership and Theology in Adelaide, SA. Vicky (like William, Peter, and current Editor John Squires) had received scholarship support from WLW to undertake doctoral research. Indeed, the very first recipient of a scholarship, the Rev. Professor Howard Wallace, was in attendance on the day., as were a number of other scholarship recipients.

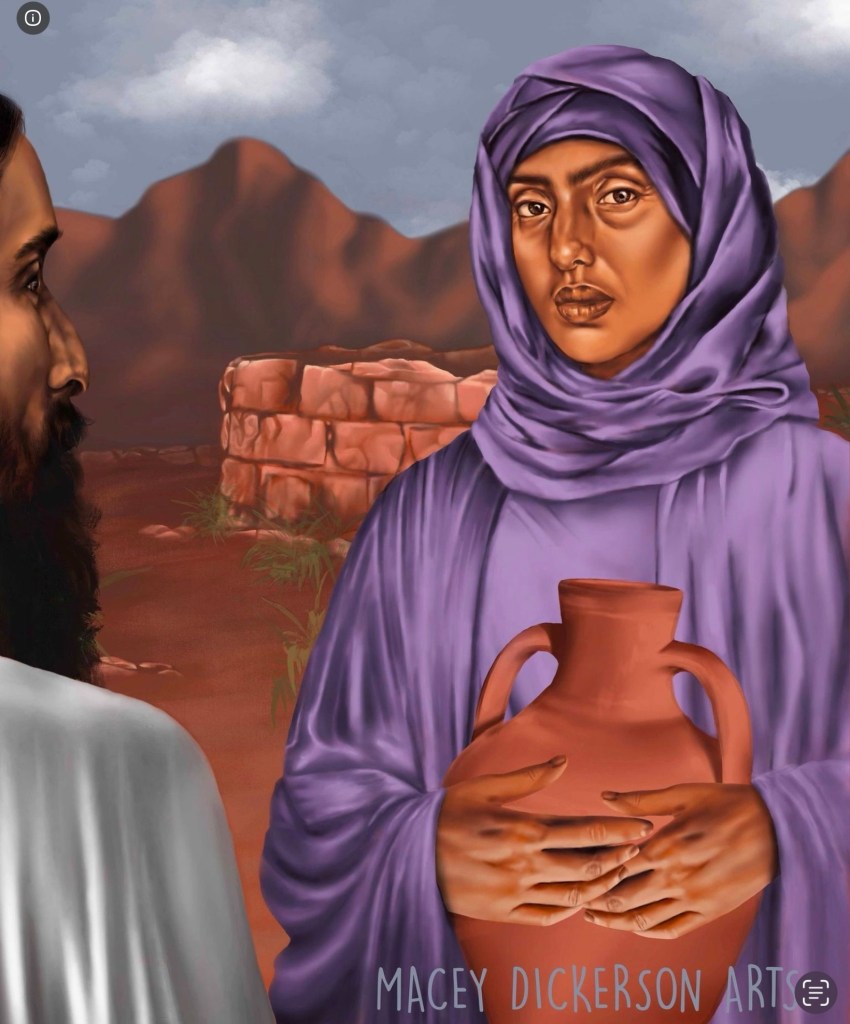

Vicky set the lectionary passage from John 4 into the context of today’s world, beset by warfare, famine, and distress. She noted that we had on the screen at the front of the church a depiction of “the woman of Samaria”—known in the Orthodox tradition as Photini, “the enlightened one”. Vicky then went on to reflect on three themes found in the story: living, flowing water; worship in Spirit and truth; and a fruitful harvest. Each, she observed, relates well to the purposes of WLW.

Macey Dickerson. Image reproduced by permission.

https://maceydickerson.com

Water runs (as it were) right through John’s Gospel, as it is found in many of the stories recorded in it: from the water in which Jesus was baptised (ch.1), through the streams of living water (ch.7), the water with which Jesus washed the feet of his disciples (ch.13), the water that flowed from the side of the crucified Jesus (ch19), to the water of the sea where the risen Jesus appeared to the disciples (ch.21).

Jesus expresses his need for water—living, flowing water. Such water rises up from the shaft of Jacob’s well, a cistern storing water, bubbling up and flowing out as a spring of living water in the encounter between Jesus and the woman. The water in this encounter reflects the changes taking place in how the woman understands Jesus—from suspicion (4:9) to recognition (4:19) to ultimate confession (4:25–26, 29) and bearing testimony about him (4:39–42). The imagery of this living, transformative water also symbolises how writers in WLW takes words of scripture and reflect on their relevance and significance in today’s world.

Worship is also a theme receiving attention in the story told by John. Ancient rivalries about the appropriate site for worship—a conflicted, but typical human question—are less significant. What matters more is how God is at work in the world, and especially how worshippers are spiritually attuned to what God is doing. The identity of the Samaritan woman had been shaped by the conflict over the sacred site; it is transformed into an openness to the ways that God’s Spirit is alive and active in the world.

That is expressed also in the title of the resource; as Vicky noted, it is not With Love to the Church, nor With Love to the Believing Christian—but With Love to the World. It is truthful, prayerful, and reflective, leading towards openness in worship.

Then, the story tells that the sowers and reapers of the harvest rejoice at the fruits they have found in the teaching of the woman amongst them. There is a big picture that we are invited to imagine, and indeed to enter. We are part of a much larger whole reflecting God’s enterprise. So today, WLW sows the seed and encourages participation in the harvesting process. “We have heard, and we know”, the villagers say; may that be the experience of those we encounter today as we share the good news.

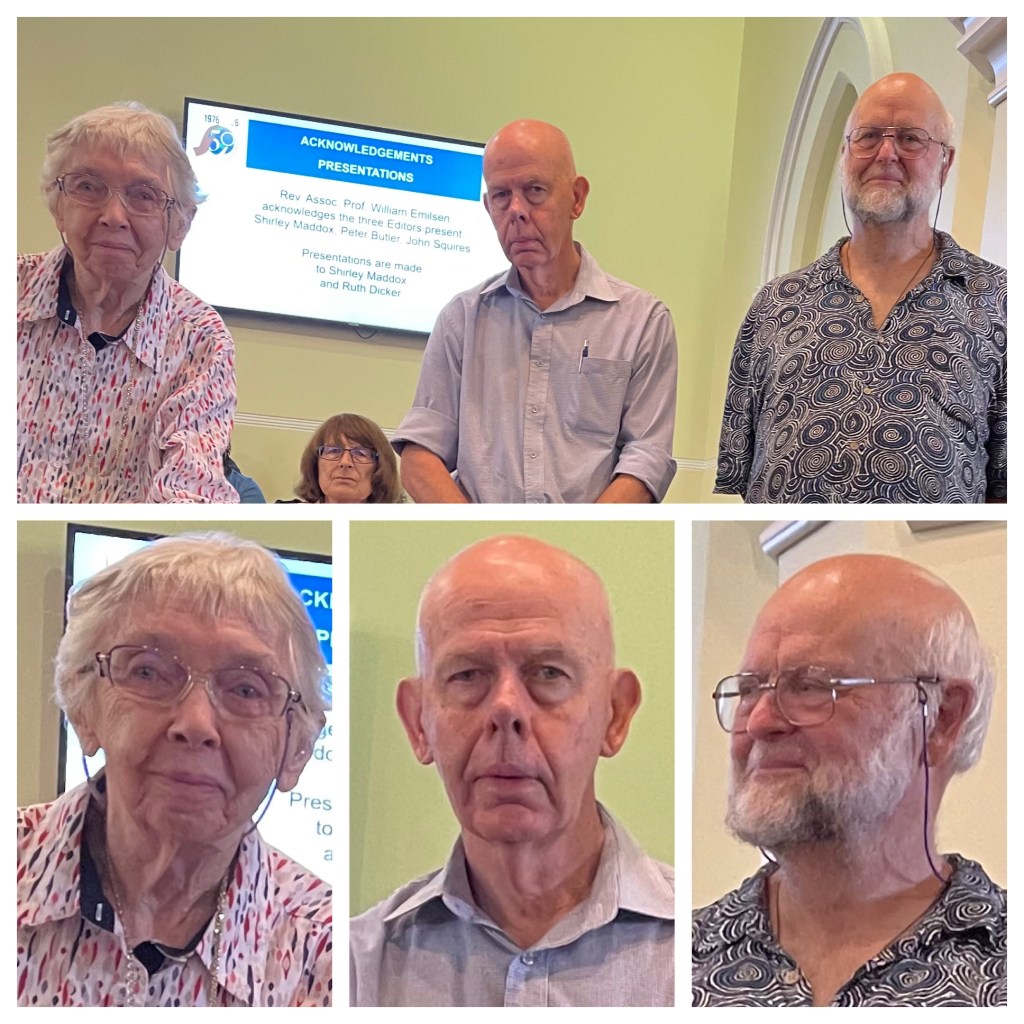

After another rousing hymn, William Emilsen acknowledged the three people who have been Editors of the resource over 47 of the past 50 years: Shirley Maddox (1979–2006), Peter Butler (2006–2021), and John Squires (since 2021). Fololeni then presented bouquets of flowers to Shirley Maddox and Ruth Dicker. As the spouses of the foundation editors, Rev. Dr Bob Maddox and Rev. Dr Gordon Dicker, and as two people always actively involved in WLW over the decades, they represent the “apostolic tradition” that continues with WLW.

Ruth then led the Prayers of the People, offering thanks for all involved in the writing and distribution of WLW, before then praying earnestly for the peace and justice we so desperate need in the world today. The service ended with a closing hymn and benediction, followed by a postlude played by the fine organist, Hugh Knight.

The congregation then moved to the hall, where a fine morning tea was enjoyed. Doug Hewitt, a member of the Strathfield church in 1976, reminisced about the very beginnings of WLW. He remembered especially the Sunday evening conversation about the lectionary passages that Bob Maddox and Gordon Dicker offered each week in “the early days”.

the gathering in the hall (centre);

Doug Hewitt and John Squires (bottom).

Two previous Editors then spoke. Shirley Maddox gave her greetings to the people; then Peter Butler explained his commitment to ensure that WLW always spoke to the everyday needs of people. Every day, he noted, someone reading WLW will be grieving, another will be hurting, another will be hoping, and yet another will be joyfully celebrating. WLW, he noted, needs to be connecting with all such people every day.

A large birthday cake was then presented; as Shirley Maddox blew out the candles, the people sang “happy birthday”—first to WLW, then again to Ruth Dicker, whose 93rd birthday occurs in the coming week. Current Editor John Squires drew the proceedings to a close with a thanks to those who had provided the sumptuous morning tea, and a reminder of his three-word commitment to ensure that With Love to the World is Inclusive—Collaborative— Diverse. And so the celebrations ended.

A WLW subscription is $28 per year. To subscribe to the hard copy booklet of With Love to the World, contact Trevor Naylor at the WLW Office on (02) 9747 1369, or email him at wlwuca@bigpond.com. To subscribe to the electronic version, download the App on your device from the App Store or Google Play.