This Sunday is the festival of Pentecost. It falls fifty days after Easter Sunday, and brings the season of Easter to a rousing conclusion. Every year, a reading from Acts 2 is scheduled. This is the account in the second volume of the orderly account of things being fulfilled that we know as the book of Acts.

Pentecost was one of the annual festivals of the Jewish people; it was known as the Festival of Harvest (Exod 23:16) or Festival of Weeks (Exod 34:22; Num 28:26-31; Deut 16:9-12). It was a significant time for Jewish people, being linked with the giving of the Law to Israel through Moses (Exodus 19–24).

The particular significance for Luke of what happened on this festival day is evident initially from its placement in the narrative as the first major event reported at length, as well as from the portentous introduction it receives, literally, “in the complete filling-up of the day of Pentecost” (2:1). The phrase recalls Luke 9:51, a similarly momentous phrase in the Gospel.

Many of the elements of this story will recur in later sections of the narrative, confirming the programmatic significance of the Pentecost account for the whole of Acts. This scene thus performs a function for Acts similar to that of Luke 4:16-31, which establishes the pattern for Jesus’ ministry in Galilee (Luke 4-9) and Jerusalem (Luke 19-21).

*****

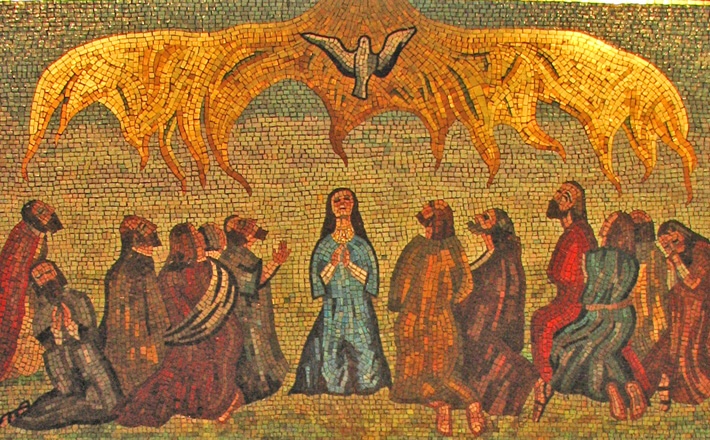

The initial action, as narrated, is a portent, comprising miraculous phenomena both auditory (“a sound like the rush of wind”, 2:2) and visual (“there appeared to them tongues as of fire”, 2:3). Such portents would be understood by any reader, in the hellenistic context, as being divine in origin. For Jews, these phenomena might evoke scriptural resonances from the story of Moses on Mount Sinai, when God gave the Ten Commandments, accompanied by thunder, lightning, thick cloud, smoke, and violent shaking of the mountain (Exodus 19:16-19).

Initially, those gathered are said to be “filled with the spirit” (2:4). In Hebrew Scripture, the spirit is known as a manifestation of God’s actions in relation to Israel, guiding selected leaders (Moses, Num 11:16-17; Joshua, Deut 34:9; Othniel, Judg 3:10; Gideon, Judg 6:34; David, 1 Sam 16:17) and inspiring various prophets (Saul, 1 Sam 10:6; 19:23-24; Isa 42:1; 61:1; Ezek 37:1; Micah 3:8).

The spirit granted specific gifts (Num 11:25; Deut 34:9; Dan 4:8-18; Prov 1:23; Joel 2:28-29) and will rest upon the future Davidic leader (Isa 11:2-5). The Priestly writer attributed the spirit with a role in creation (Gen 1:1-2; see also Job 33:4) and the Psalmist envisioned the spirit as playing an eschatological role (Ps 104:30).

Luke has noted the strategic role of the spirit in the lives of Jesus (Luke 4:1) and John the baptiser (Luke 1:15), as well as of John’s parents (Elizabeth, Luke 1:41; Zacharias, Luke 1:67). The giving of the spirit at Pentecost thus stands in continuity with God’s actions in Israel; it also prefigures the state of many individuals later in the narrative of Acts (4:8; 6:3,5; 7:55; 9:17; 11:24; 13:9; and cf. 18:25). The Pentecost narrative signals that the spirit is to be an integral factor in leadership of the messianic movement.

The action of the spirit immediately results in ecstatic phenomena, as “they began to speak in different tongues” (2:4). This phenomenon recurs in Caesarea (10:46) and in Ephesus (19:6). Often, the gift of tongues has been taken as being the key element in this narrative. In the light of the comment of the bystanders (2:7-8), it cannot be doubted that Luke understands the phenomenon to be “xenoglossy”, that is, the way that individuals miraculously spoke publically in identifiable foreign languages.

This is different from the “glossolalia”, or speaking in unknown languages in a private prayer-like communication with God, which Paul reports in 1 Cor 12-14; although it is entirely plausible that Luke has reinterpreted such a phenomenon as “xenoglossy” for his own purposes (Wilson 1973:121-122). For Luke, the foreign languages which were spoken begin to fulfil Jesus’ prediction that the message was to be preached in every nation (Luke 24:47-48; Acts 1:8). This is the programme which now begins to be implemented in Acts; the spirit of prophecy gives an empowering for witness (Turner in Marshall and Peterson 1998:327-348).

*****

Luke 24:53 leads us to expect the location of the Pentecost story to be in the temple; certainly, it soon becomes explicit that events occur in Jerusalem (2:5). The ”Jews, devout men (sic.) from all the nations under heaven” who are present are identified as having come to live in Jerusalem from the nations at the eastern end of the Mediterranean basin (2:9-11), in four quadrants with Jerusalem at the centre.

The scene already points to events later in Acts; although the particular setting is the Jewish context of festive Jerusalem, this gathering from the nations surrounding Jerusalem foreshadows the wider awareness of the Gospel which is to come. However, for the moment, the focus remains strictly Jewish, both in terms of the individuals who are present (“Jews”, 2:5) and in terms of how the story echoes the prophetic vision of the eschatological gathering of the nations (see Isa 2:2-4; 34:1-4; 42:1-6; 43:8-9; 45:20-23; 49:22-23; 52:7-10; 55:1-5; 60:1-7,11,14; 62:1-2; 66:18-24. At Isa 11:12 it is ”the outcasts of Israel and the dispersed of Judah” who are gathered.)

It is a deliberate narrative decision to portray God acting amidst this gathering of diaspora Jews. For the crowd of pilgrims the precise action narrated is unexpected and is capable of diverse interpretations (“all were amazed”, 2:12; “others sneered”, 2:13).

Peter offers what, for Luke, is the definitive interpretation: “this is what was spoken by the prophet” (2:16). In speaking in this way, Peter not only refers to the prophetic words of Joel, but also functions himself as a prophet, in that he sets forth the divine perspective on the events that are taking place. What has taken place is what God said he would do “in the last days” (2:16-17). The event has deep and enduring significance.

*****

The speech offers an interpretation of the phenomena which have just been experienced, through recourse to scripture (2:14-21). This is Peter’s second speech and, like his first, it is grounded in scripture. Fulfilment of prophecy which is reported here is a strong thematic strand which runs throughout Acts. It is the most explicit of a range of ways in which scripture figures in his narrative; for Luke, scripture is the matrix which will provide full understanding of the events he narrates.

The citation of “what was spoken through the prophet Joel” in 2:17-21 already contains more than adequate points of connection with the immediate context: reference to the spirit (2:17,18; see 2:4), prophecy (2:17; this appears to be the force of 2:7-11), and wonders (2:19; again, this describes 2:2-4).

It will also provide points of connection with subsequent events in other places: male prophets (11:28; 21:10-11); female prophets (21:9); the seeing of dreams and visions (9:10; 10:3,10-12; 12:9; 16:9; 18:9; 22:17-18; 23:11; 27:23) and the granting of salvation to those who “call on the name of the Lord” (4:12; 16:31). This scripture citation thus has a strategic significance in terms of the ensuing narrative.

The particular version of the scriptural text that Luke cites intensifies these connections with the immediate events, thereby highlighting the way he wishes them to be interpreted. The emphatic “God says” (2:17) makes explicit the intention of the prophetic oracle, that these phenomena are divinely given (“I will pour out my spirit”, 2:17; “I will give wonders”, 2:19).

In Luke’s version of the text, the divine gift of prophecy is (2:17) is repeated in the phrase “and they will prophesy” after the reiteration of “I will pour out my spirit” (2:18), and the divine portents are emphasised through the inclusion of signs after the reference to wonders in 2:19. Each of these gifts recur throughout the narrative of Acts: prophecy at 11:28; 19:6; 21:9-11, and signs and wonders at 4:30; 5:12; 6:8; 14:3; 15:12.

Finally, the inclusion of a reference to “in the last days” (2:17) heightens the significance of the event as the beginning of eschatological fulfilment. The interpretation which Luke has Peter provide thus uses language about God to elucidate the inner significance of the Pentecost phenomena. Interpreting the tongues and wonders as divine gifts provides a paradigm for understanding subsequent occurrences of such features in the later narrative.

*****

Towards the end of his speech, Peter uses a number of terms to interpret the manifestation of the spirit. It is said to be “poured out” at Pentecost (2:33). The same term recurs in the description of events in Caesarea (10:45). The parallelism between events in Jerusalem and Caesarea is reinforced when Peter declares that “they received the holy spirit as we also did” (10:47; see also 11:15,17). However, it is not just this one subsequent event which is patterned on the Pentecost Day experience. The terminology of “receiving the spirit” (2:38) occurs not only in Caesarea (10:47), but also in Samaria (8:15,17,19) and Ephesus (19:2), as well as Jesus’ own case (2:33).

Peter describes the spirit as a gift (2:38); he continues to interpret the spirit in this way in later speeches (5:32; 10:45; 11:17; 15:8). Peter also notes that such a gift is the fulfilment of the promise (2:33,39) which was spoken of by Jesus (Luke 24:49; Acts 1:4). He associates it with the forgiveness of sins, not only in his Pentecost speech (2:38) but also in subsequent speeches (5:31; 10:43); the same link is made by Paul in Pisidian Antioch (13:38). Thus, the Pentecost narrative introduces the central elements of the role accorded to the spirit in the ensuing narrative.

This blog is based on a section of my commentary on Acts in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, ed. Dunn and Rogerson (Eerdmans, 2003).

See also https://johntsquires.com/2019/06/03/ten-things-about-pentecost/