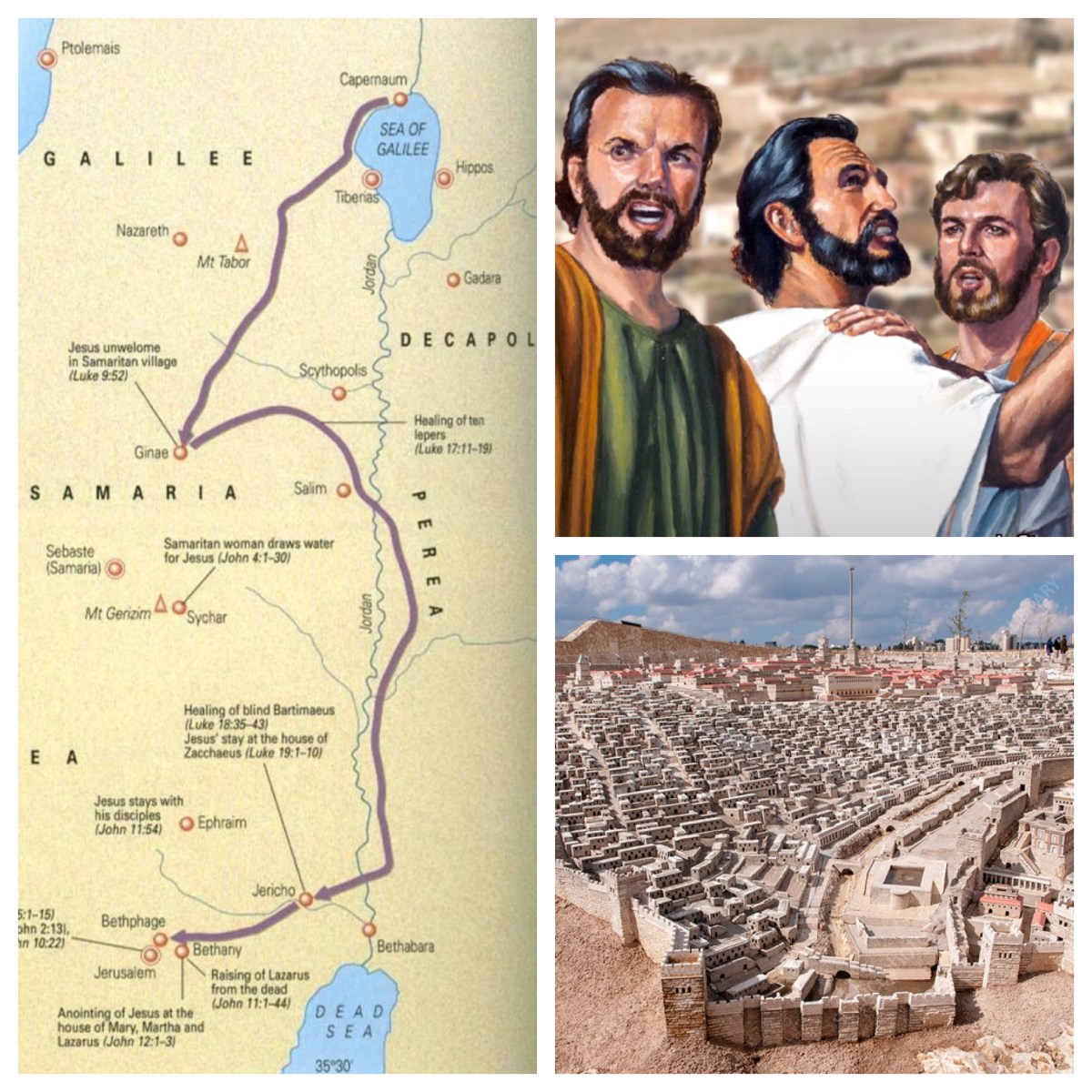

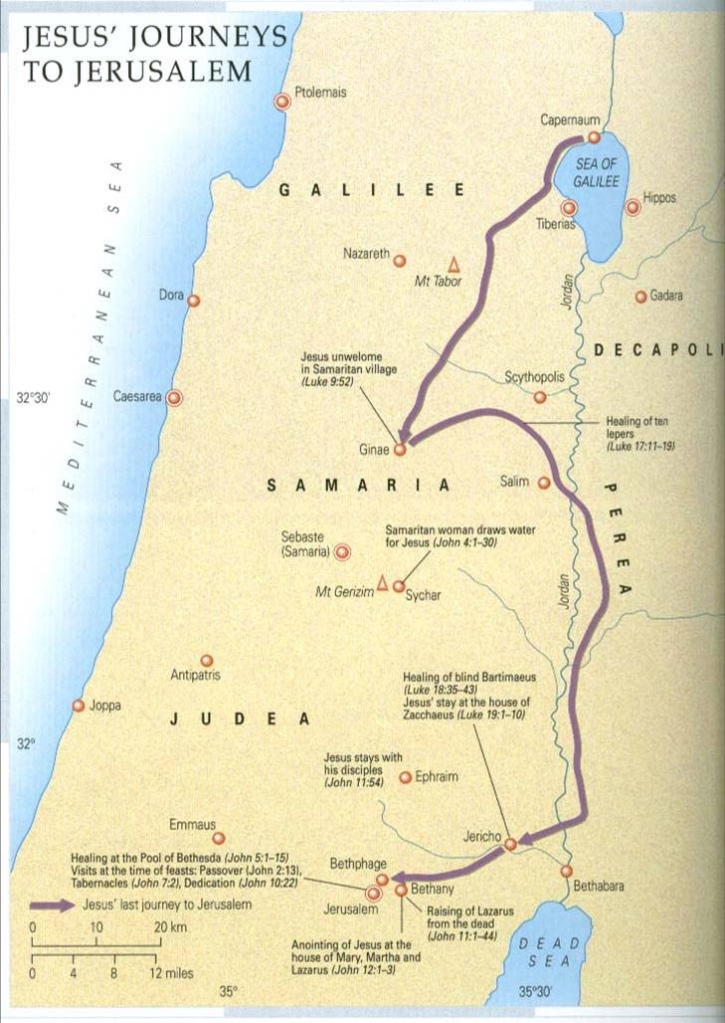

Jesus came from Nazareth in Galilee, in the northern region of Israel. His childhood and much of his adult life was lived in Galilee. Like many others of his time, that life included trips to Jerusalem, the city where kings had ruled; where the Temple sat at the pinnacle of Mount Zion; where sacrifices and offerings were presented to God; where festivals were celebrated, sins were forgiven, gratitude was expressed, psalms were sung.

But Jesus spent most of his time in Galilee, in the northern region of Israel, visiting the synagogues, encountering people on the streets, spending time at table with various people. There was a moment in time, however, when he made the decision to go to Jerusalem. It was a momentous decision; indeed, it would be a fatal decision, as it turned out. But at the time, nobody knew that would be the case. He had travelled south to Jerusalem, and then returned north to Galilee, on occasions before. But this time would be different. His disciples didn’t know that. Did Jesus himself have any inkling about this?

Towards Jerusalem

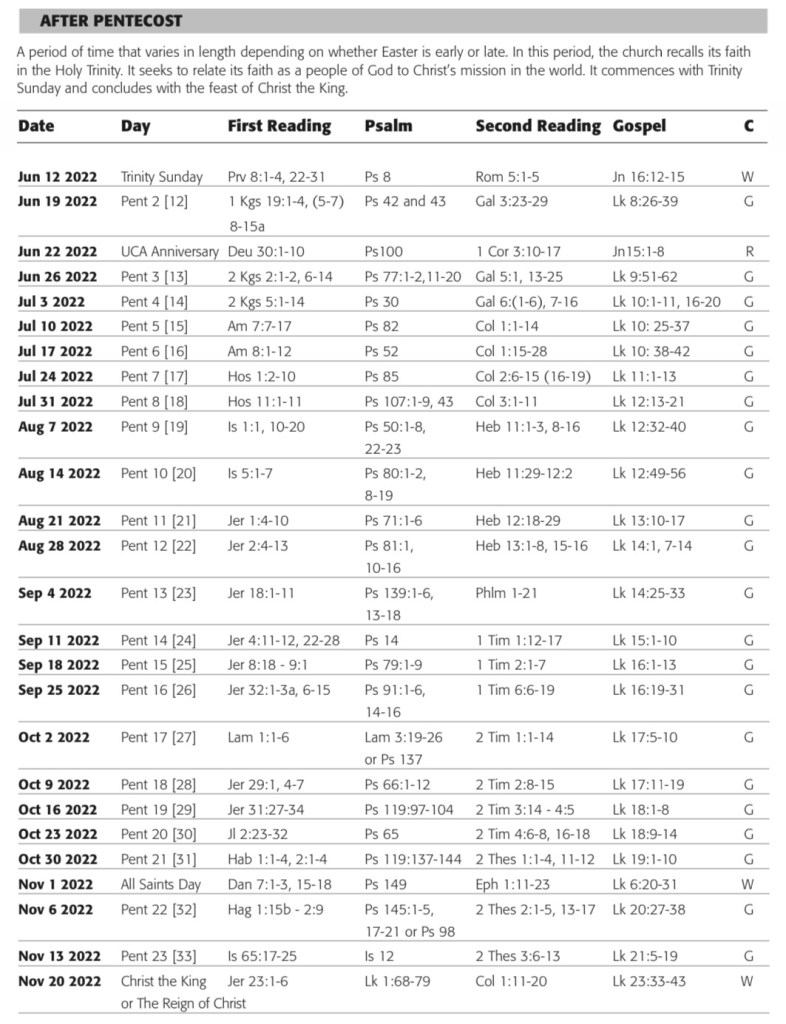

In the reading that the lectionary offers for this coming Sunday (Luke 9:51–62), we hear that Jesus “set his face to go to Jerusalem” (Luke 9:51). Then follows quite a saga, as that journey unfolds over ten full chapters. Matthew and Mark, by contrast, simply report that “he left that place [Galilee] and went to the region of Judea and beyond the Jordan” (Mark 10:1; Matt 19:1). Short, simple, quick. Yet Luke makes a big deal of it. It was a momentous decision.

As Mark reports Jesus’s journey to Jerusalem, he notes that “crowds again gathered around him; and, as was his custom, he again taught them” (Mark 10:1). But what he taught is not evident; Mark does not report many more details. Instead, Jesus is suddenly “in the region of Judea, beyond the Jordan” (Mark 10:1), back where he was first baptised (Mark 1:5). Soon, he would enter the city and then the Temple (Mark 11:11–15). It all takes place quite rapidly.

By contrast, in Luke’s orderly account of the things that have been fulfilled amongst us, the journey to Jerusalem, which begins at Luke 9:51 (“when the days drew near for him to be taken up, he set his face to go to Jerusalem”) takes ten full chapters to narrate. Jesus sets his face to Jerusalem at 9:51. He does not actually begin to approach Jerusalem until 19:11. Even then, his entry to the city is drawn out; Jesus tells a parable (19:11–27), rides down from the Mount of Olives on a donkey (19:28–38), and weeps over the city (19:39–44); then when he enters the city, he goes immediately to the temple (19:45).

Luke takes almost ten full chapters to narrate the journey that Jesus took, with his disciples, including much material that is found only in his narrative. What he taught on that journey, who he encountered on the road, and those whom he healed and exorcised along the way, are all reported by Luke. On this journey in Luke’s Gospel, see

The decision Jesus makes to travel to Jerusalem is reported in terms of weighty theological significance (9:51-56). “When the days drew near for him” might literally be rendered, “in the filling up to completion of the days”; the verb is an intensifying compound of pleroō, meaning to come to fruition or to be filled up.

Pleroō is the same verb used at the start of Luke’s narrative, at 1:1, where it also has a heavy theological sense (the things that God was bringing to fulfilment or completion). It also appears at the end of the narrative, when Jesus refers everything written about him “in the law of Moses and the prophets and the psalms” being fulfilled in accord with divine necessity (24:44).

The word appears also within the body of Luke’s narrative in relation to the fulfilment of scripture (4:21), the fulfilment of the time of the nations (21:24), and the fulfilment of the kingdom (22:16). And quite significantly, the exact same phrase introduces Luke’s account of the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:1). It is a signal that something very important is taking place.

The compound verb sumpleroo, which Luke uses at 9:51 and also at Acts 2:1, appears four times in the Septuagint, an early Greek translation of Hebrew Scripture. All four times it refers to the destruction of Jerusalem in 587BCE, and the seventy years that it lay fallow before the Israelites could return. So it is used with a weighty theological significance there, underlining its importance when it appears in Luke’s account.

(The other use of this compound verb is at Luke 8:23, in the account of the journey across the lake, when the boat in which Jesus and his disciples were sailing “was filling with water, and they were in danger” (8:23). The sense here is more prosaic—water is swamping the boat—but perhaps the linking of this word with “and they were in danger” points to the risk that Jesus was taking as he ventured across the lake, into Gentile lands, where he encounters the man possessed by a Legion of demons. See https://johntsquires.com/2022/06/14/what-have-you-to-do-with-me-jesus-luke-8-pentecost-2c/)

The phrase translated as “to be taken up” is analēmpsis, which could also be translated as “ascension”; the verb is used of Jesus rising into the clouds at Acts 1:2, 11, 22. This, of course, is the climactic moment at the end of the Gospel (Luke 24:50–51) and the opening scene of the second volume (Acts 1:6–11). That scene is in view from this earlier place in the narrative.

And when we read that Jesus “set his face to go to Jerusalem” (9:51), the language indicates a steely resolve, a fixed determination, to head towards the city. The verb used here is found in the LXX to refer to God’s determination (Lev 17:10; 20:3–8; 26:17; Ezek 14:8; 15:7) and it forms a consistent refrain in God’s directions to the prophet Ezekiel (Ezek 4:3, 7; 6:2; 13:17; 20:46; 21:2; 25:2; 28:21; 29:2; 35:2; 38:2). Jesus turns to Jerusalem with a fixed prophetic intent; when he arrives in the city, it is “a visitation from God” (19:44).

Through Samaria

The determination that Jesus had to press on, heading south through Samaria, towards Jerusalem, is picked up by his disciples. Although some are sent on ahead into Samaria to make preparations from his coming, when Jesus and his group arrive, they encounter resistance from the Samaritans (9:52–53). It is presumed that the Samaritans, reflecting traditional antagonism between the two regions (as is reported at John 4:9), were not willing to provide hospitality to one known to be heading to the southern capital.

Incensed by this lack of support for their band as they made their way through the region, James and John said, “Lord, do you want us to command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?” (9:54). Their cry evoked a scene from the time of the king, Ahaziah, as two separate groups of fifty soldiers were consumed by fire when Elijah petitioned the Lord, “let fire come down from heaven and consume you and your fifty [men]” (2 Kings 1:10, 12). God had acted with vengeance in the past; surely God would do the same once more, the disciples presumably reasoned.

God did not intervene. Jesus was not pleased. He rebuked them (9:55) and they moved on to the next village. The comparison with Elijah is deemed inappropriate, at least at this point. (Later manuscripts from the medieval period add an explanation as to why Jesus rebukes them: “the Son of Man has not done to destroy the lives of human beings, but to save them”. The addition follows the form of the saying of Jesus recorded at Mark 10:45, and the substance of the saying at John 3:17. There are, however, no similar sayings in Luke’s narrative.)

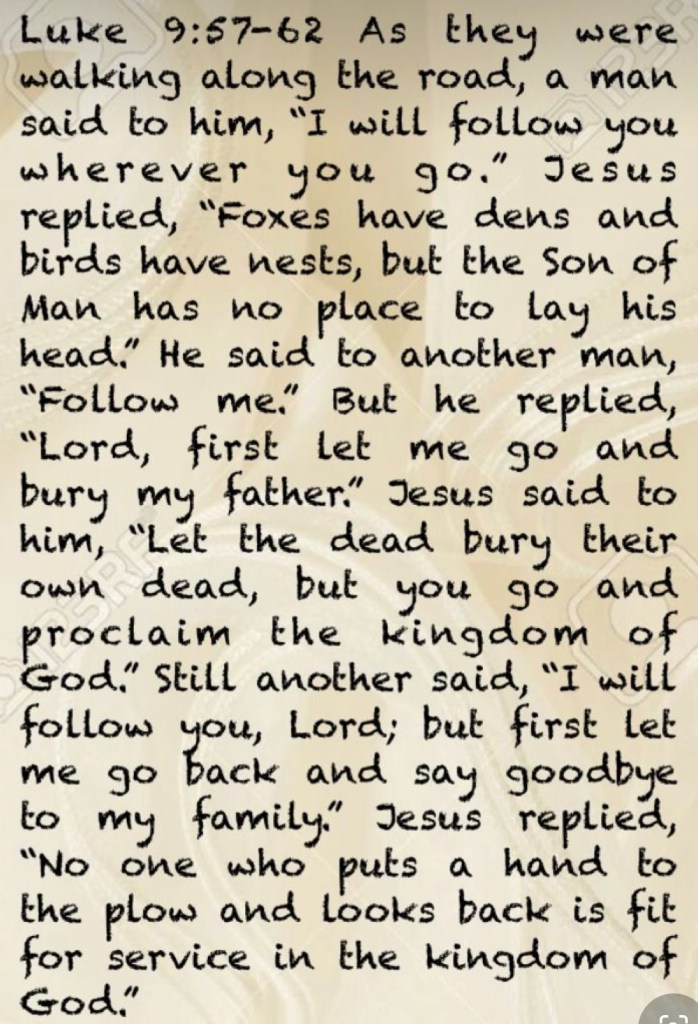

The final section of the passage offered by the lectionary focuses on the singularity of purpose required to follow Jesus. The call to follow (implicit at 5:10–11; explicit at 5:27; 9:23; see also 14:27; 18:22) is here intensified by the collating together of three originally independent sayings of Jesus.

The first and third sayings are spoken in response to an approach to Jesus, “I will follow you”. The first occurrence (9:57) is an absolute statement; it evokes the response, “foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (9:58). That is the same response which Jesus gave to a scribe who utters the same affirmation in Capernaum, much earlier in Jesus’s time in Galilee, in Matthew’s account (Matt 8:20).

The third occurrence (9:61) is conditional; “let me first say farewell to those at my home.” The response from Jesus, “no one who puts a hand to the plow and looks back is fit for the kingdom of God” (9:62) is found only in Luke’s narrative. The saying evokes the scene where Elisha is called by Elijah, but seeks to say farewell to his father and mother before following (1 Kings 9:19–21). Elijah permitted this last act of familial duty, before Elisha “set out and followed Elijah, and became his servant” (1 Kings 19:21).

Jesus, by contrast, will not countenance any conditional response; it must be a total commitment, if you wish to follow him. “Whoever comes to me and does not hate father and mother, wife and children, brothers and sisters, yes, and even life itself, cannot be my disciple”, he would later say (14:26). Refusing to allow the person to “look back” perhaps has in mind what happened to Lot’s wife, who “looked back and she became a pillar of salt” (Gen 19:26).

The middle saying of Jesus is a call spoken directly to one person, “follow me”, which is met by a conditional response: “first let me go and bury my father” (9:59). This response is also linked with the first response (“foxes have holes …”) in Matthew’s account (8:19–22). Jesus, of course, is unwilling to accept such a conditional response; he demands full and intense loyalty. (The words of Jesus, responding to Peter at Luke 18:29, verify this.) His rejoinder in both accounts is to “let the dead bury their own dead” (Luke 9:62; Matt 8:22); in Matthew, it is linked with the charge to “go and proclaim the kingdom of God.”

The call to follow Jesus will be put to the test immediately after this, when seventy of the followers of Jesus are sent out, two-by-two, charged to “cure the sick who are there, and say to them, ‘The kingdom of God has come near to you’” (10:9). That part of the story is what is provided by the lectionary for the Sunday after this coming Sunday (so see next week’s blog!).