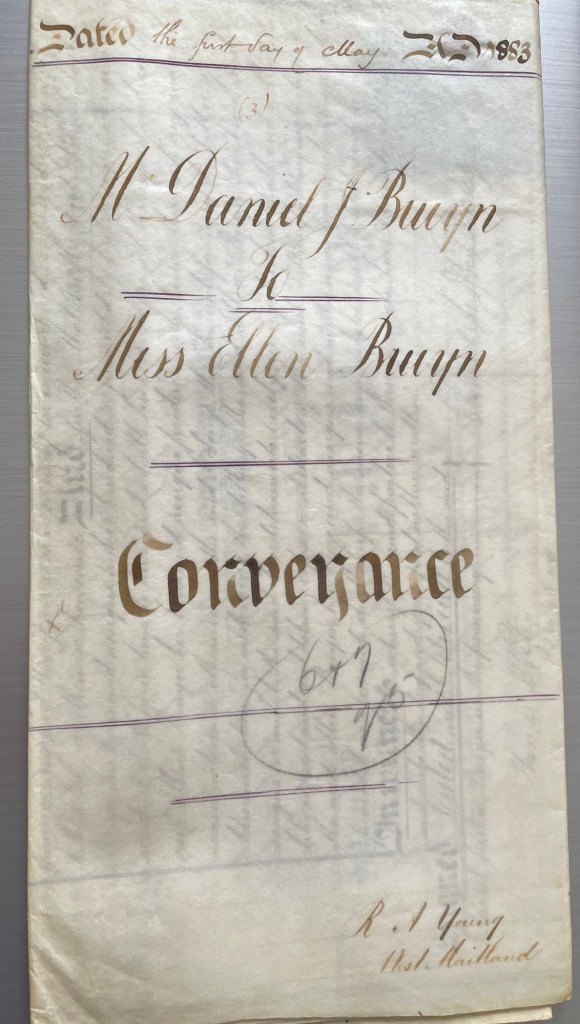

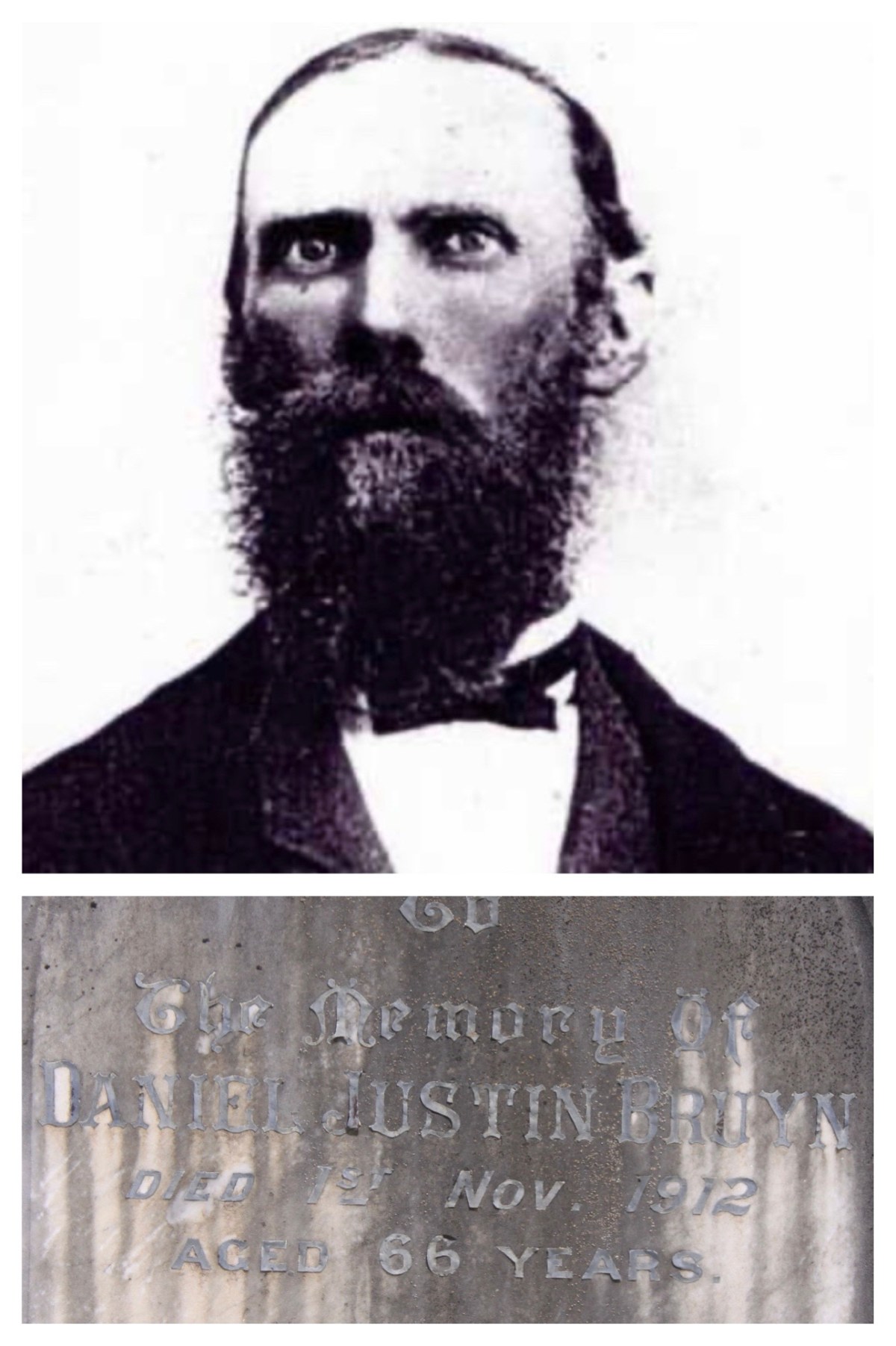

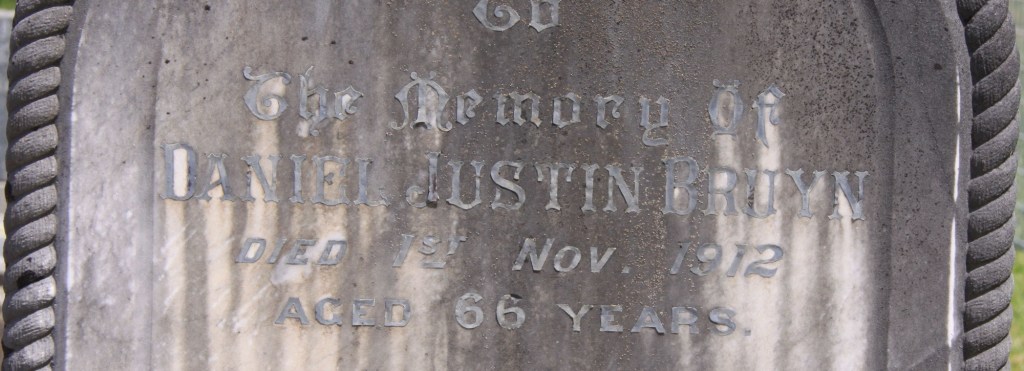

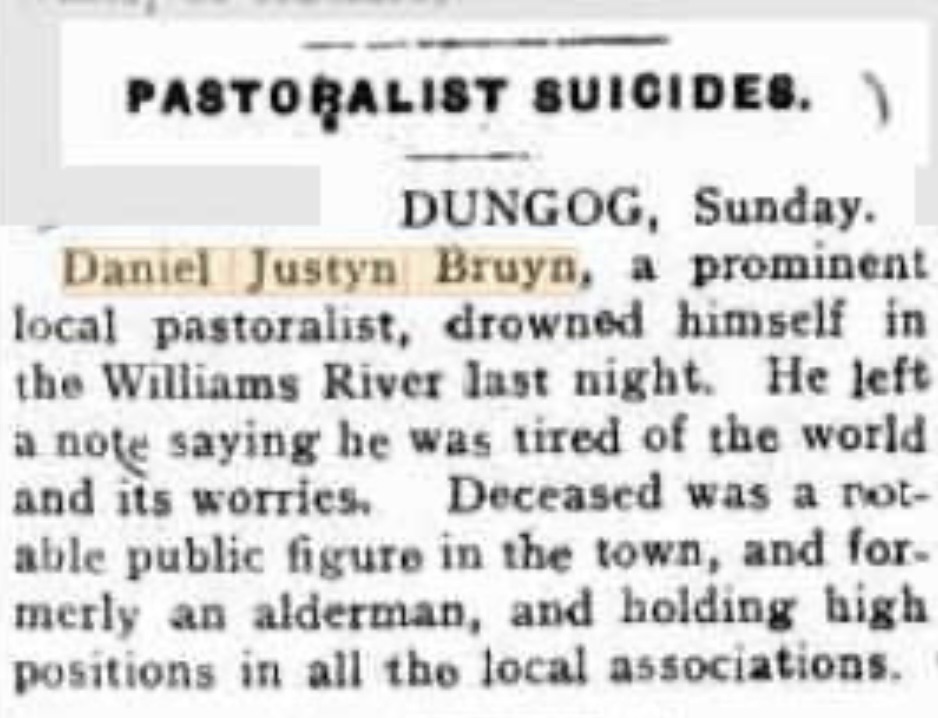

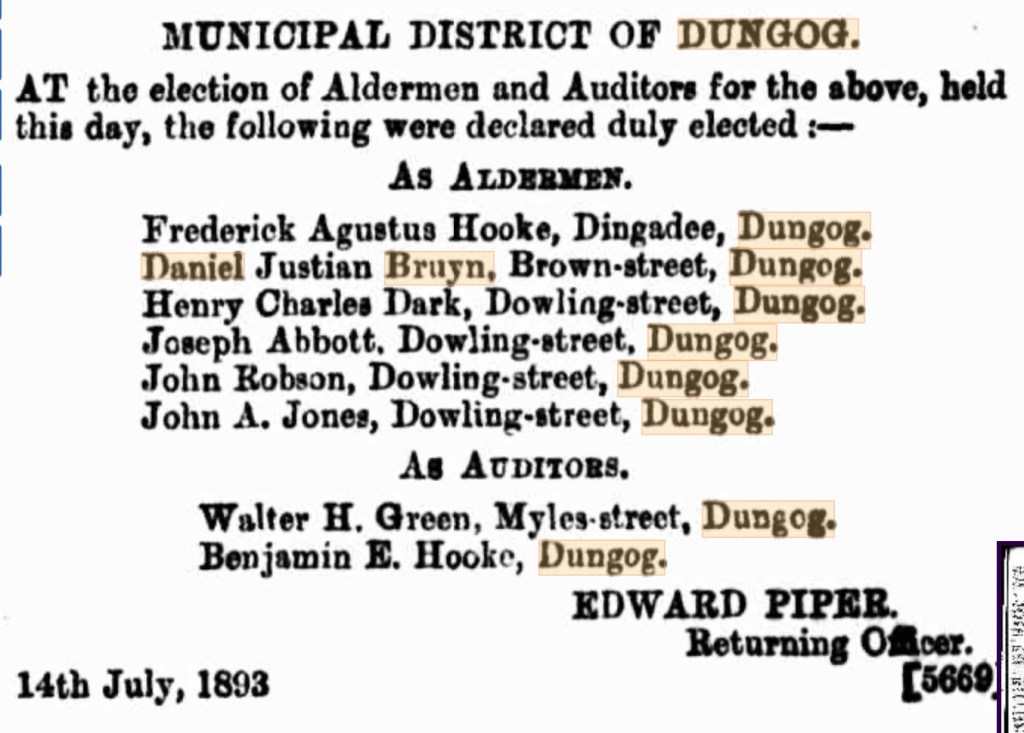

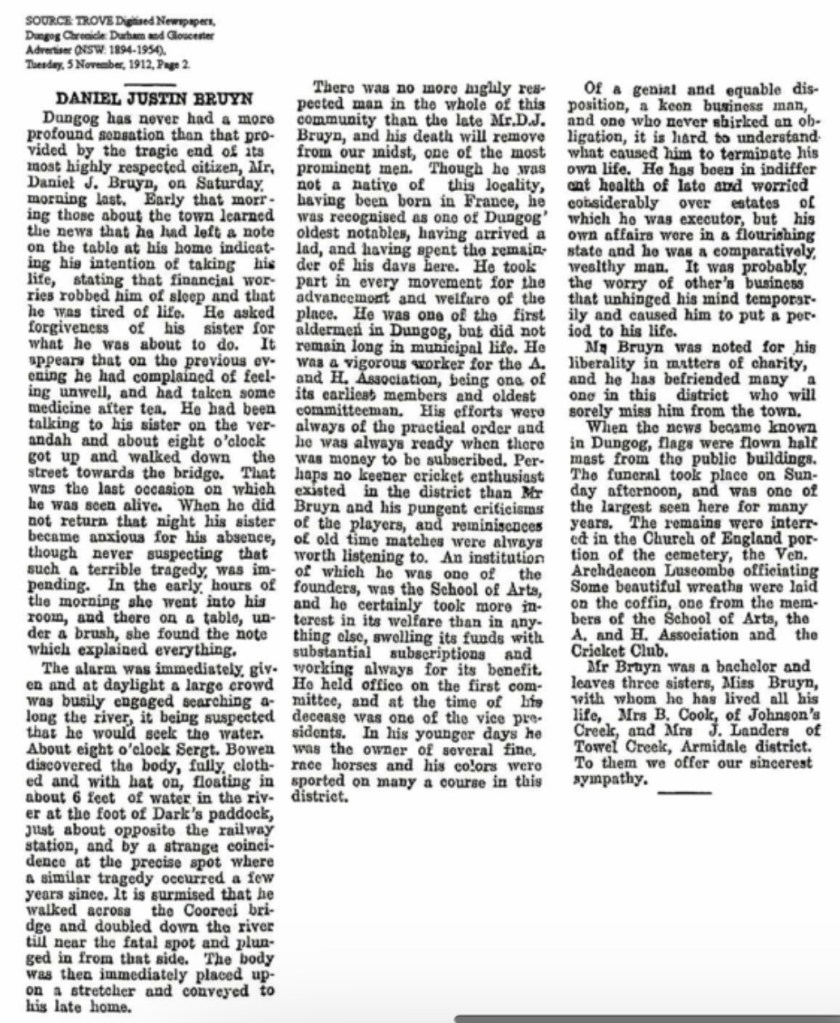

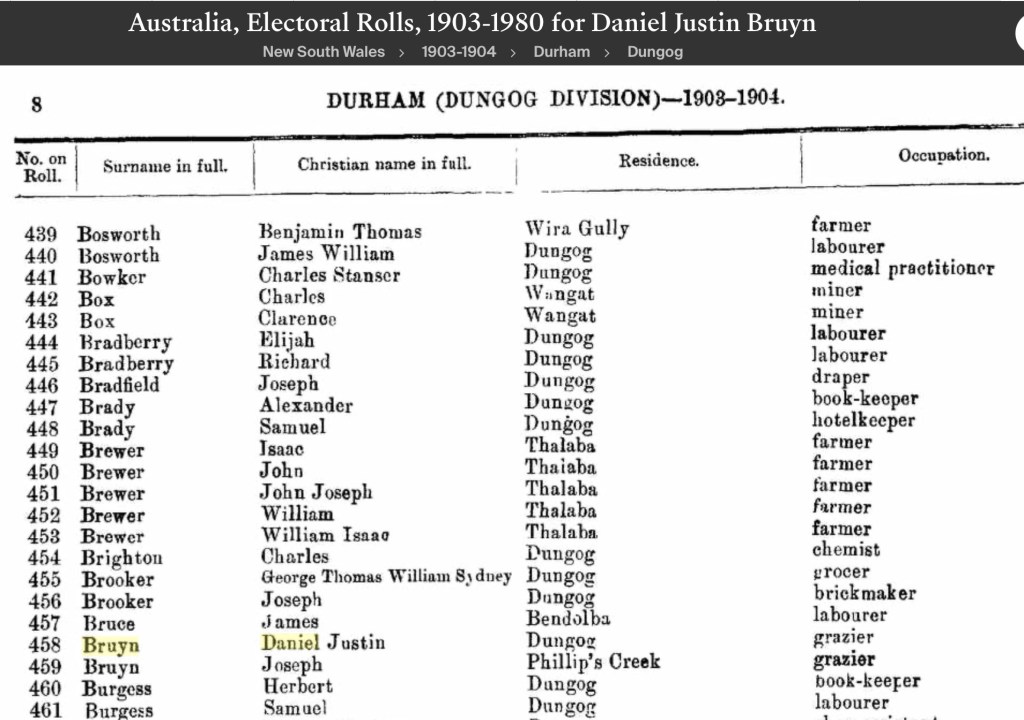

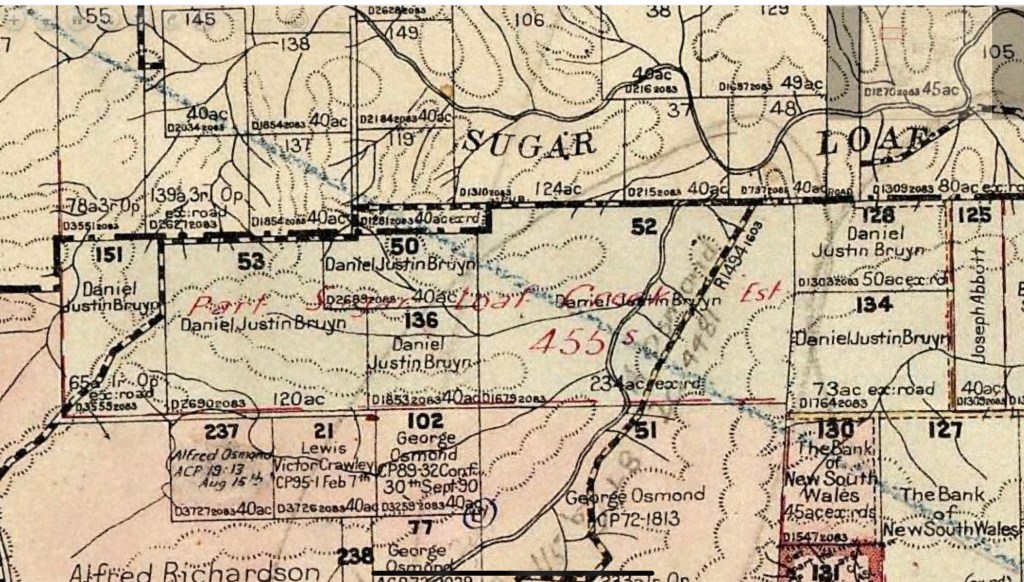

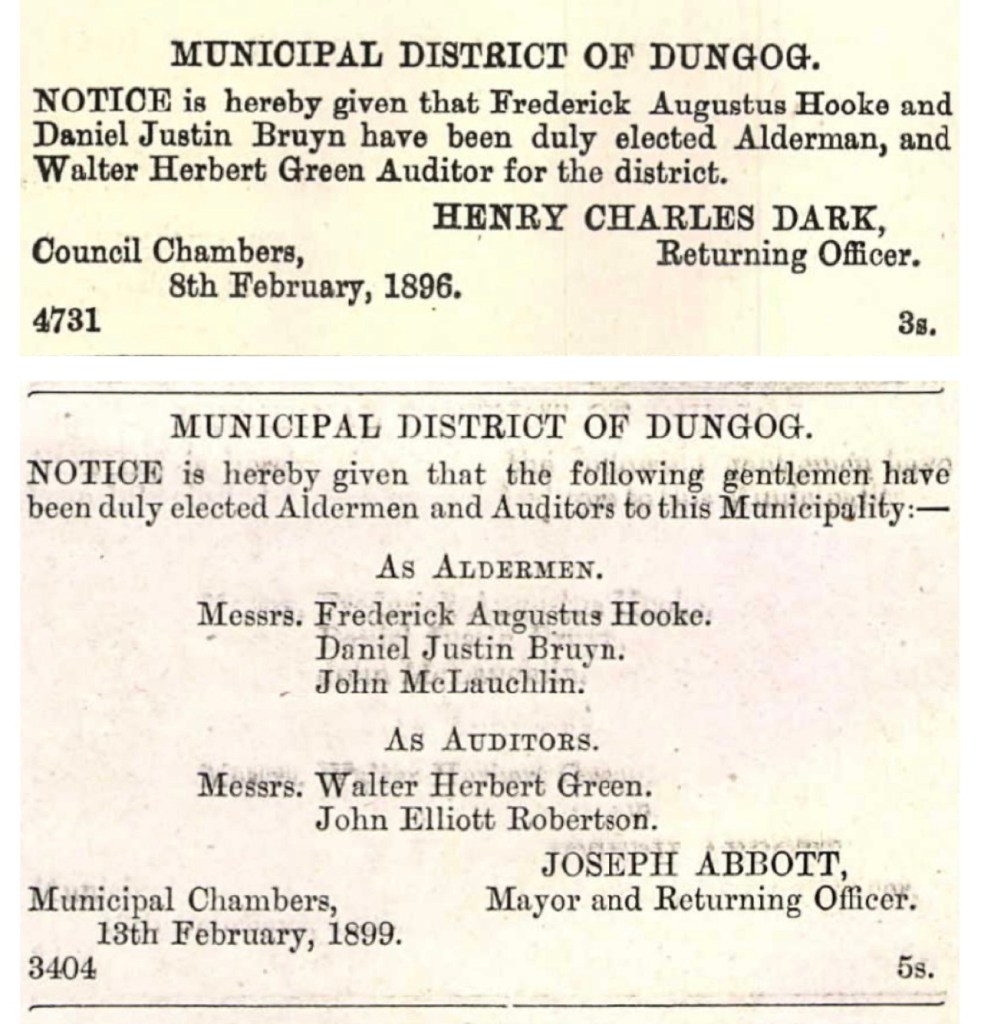

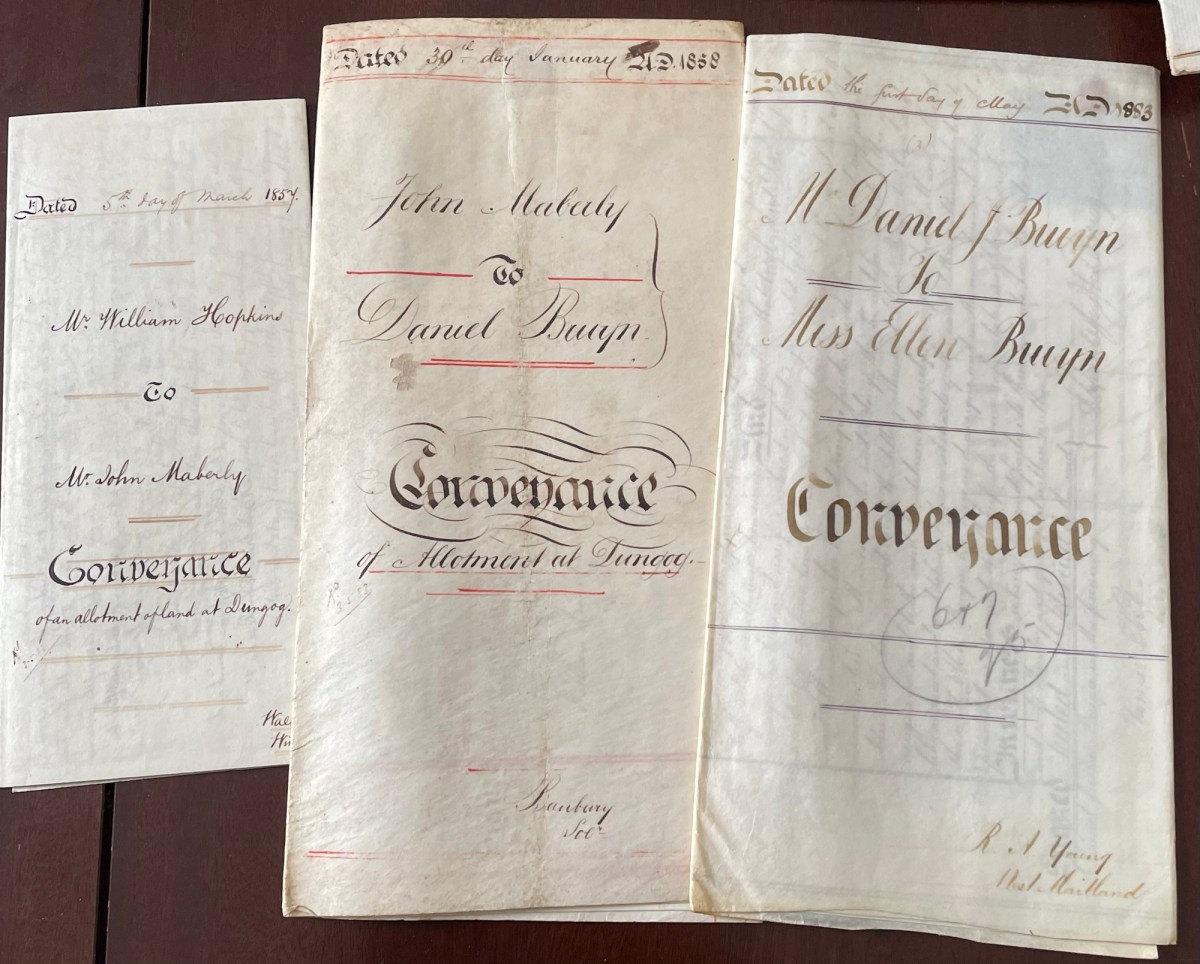

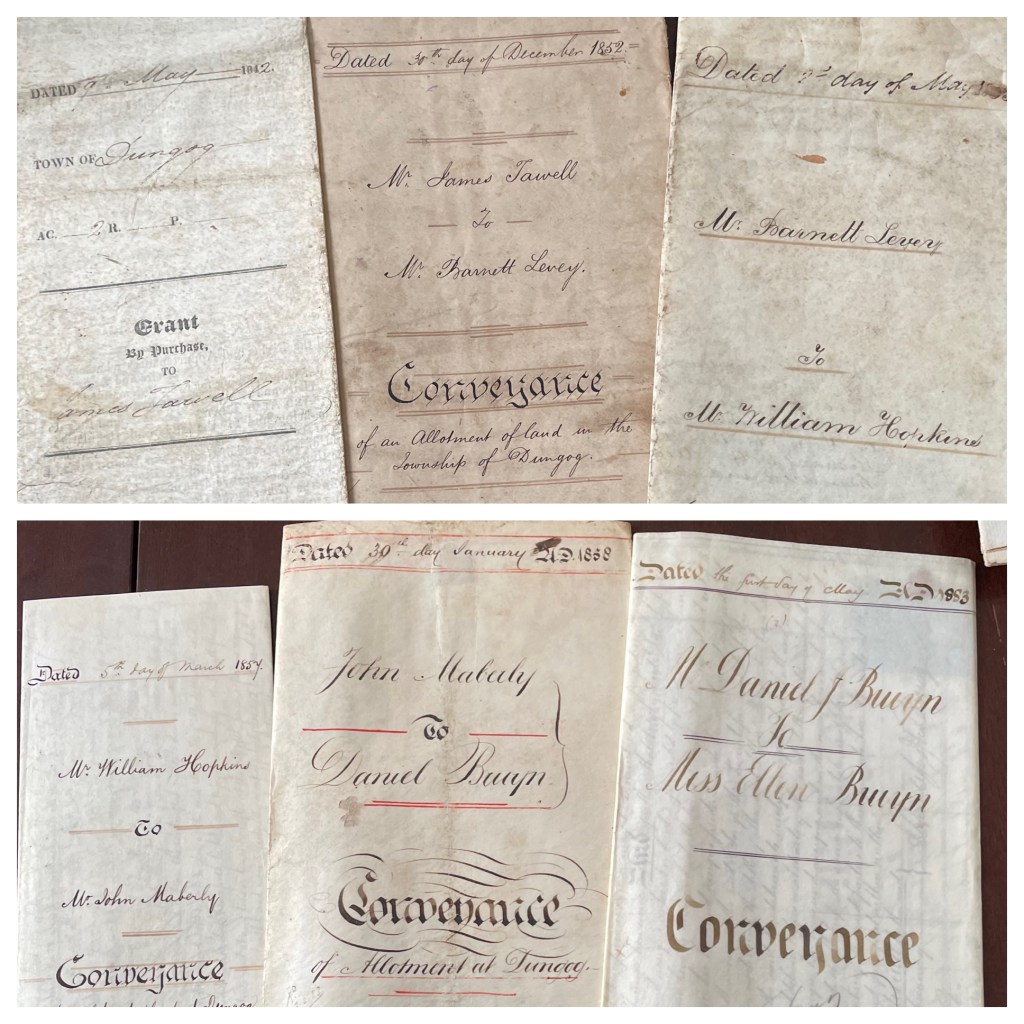

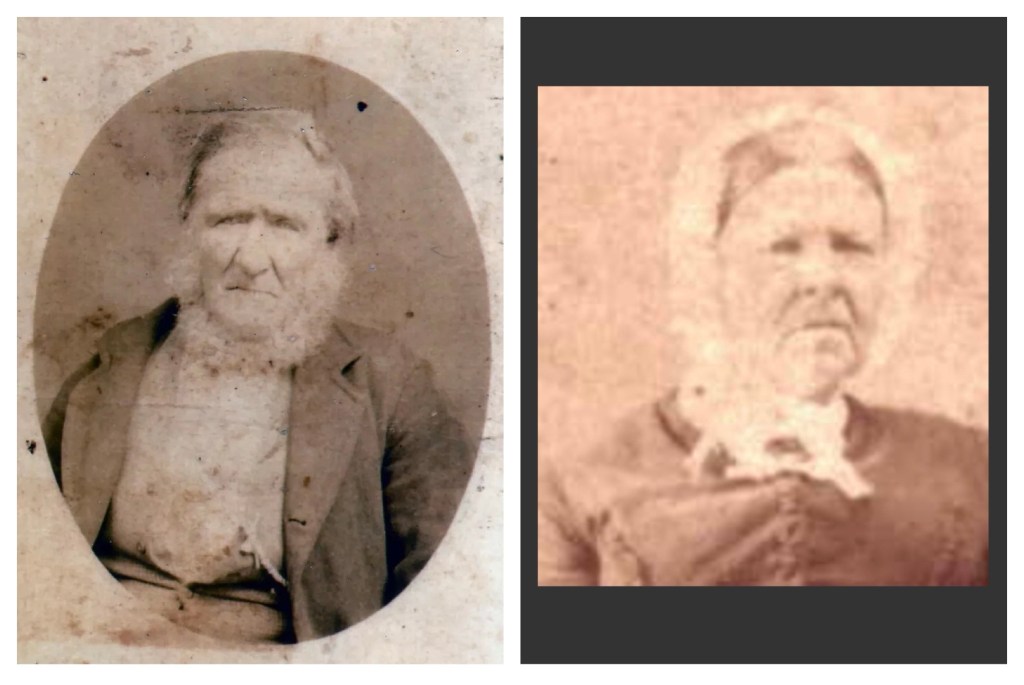

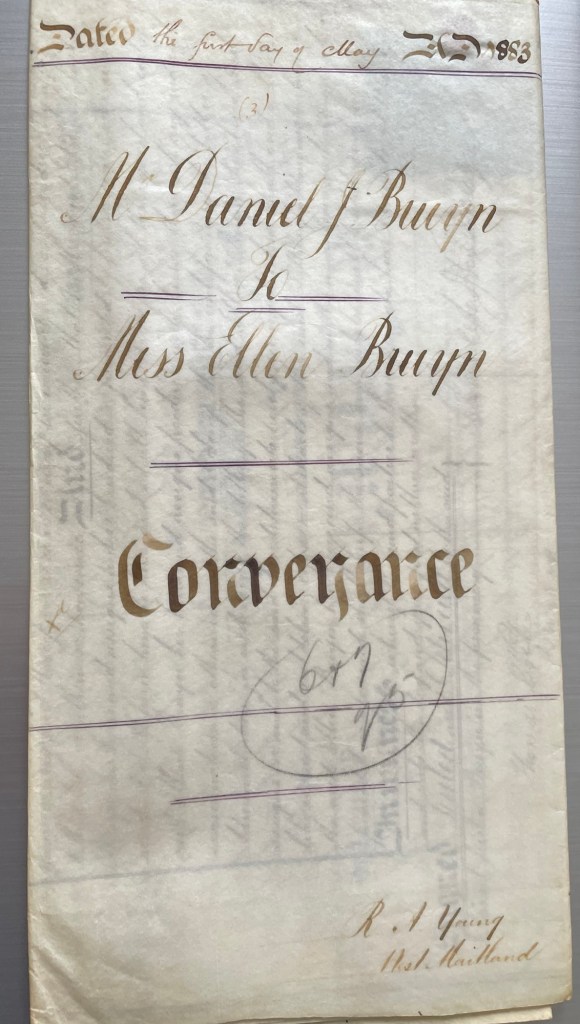

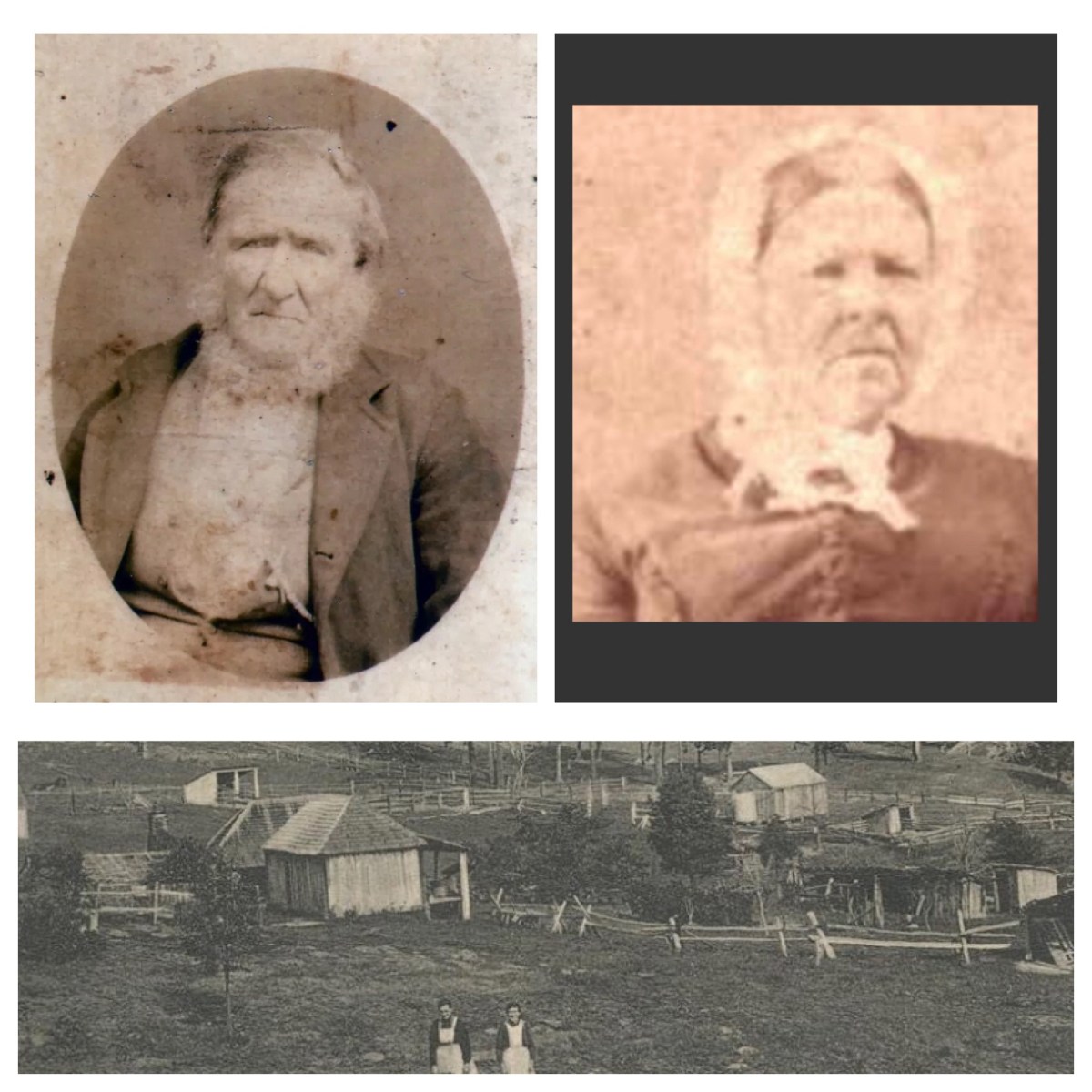

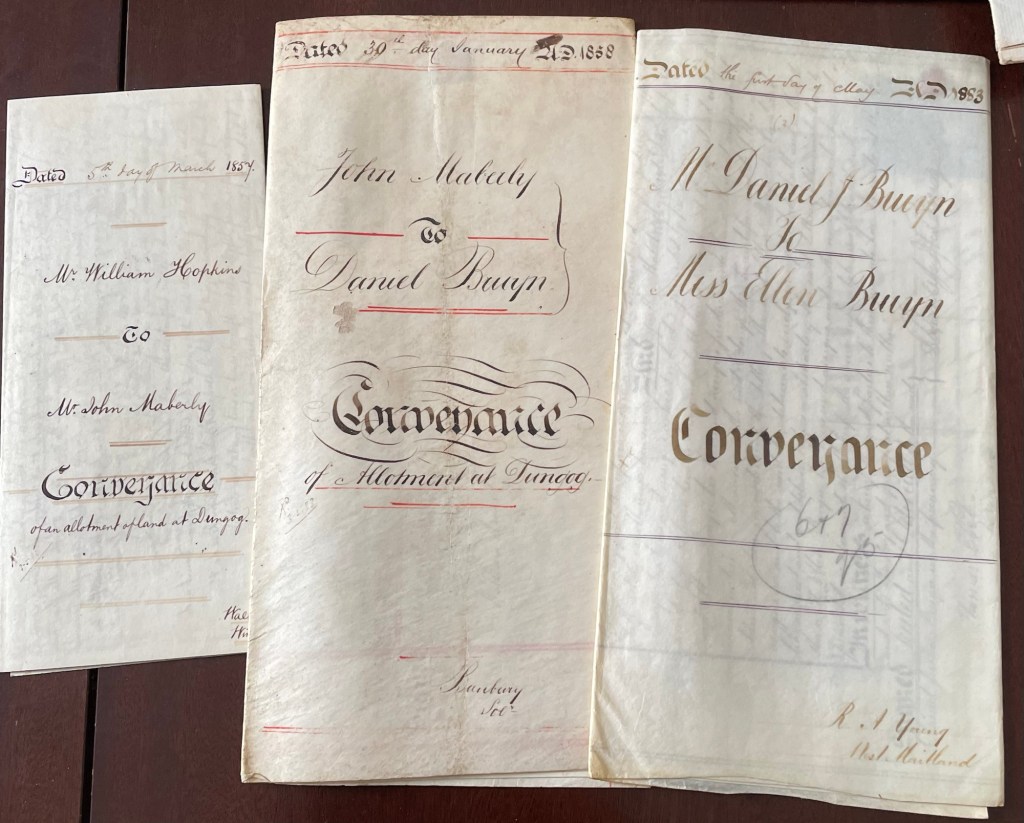

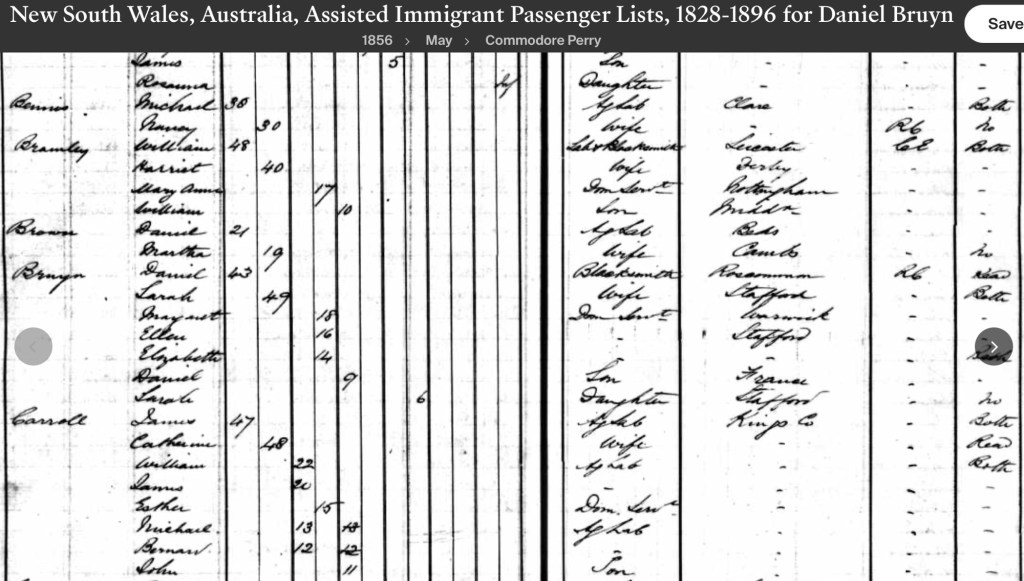

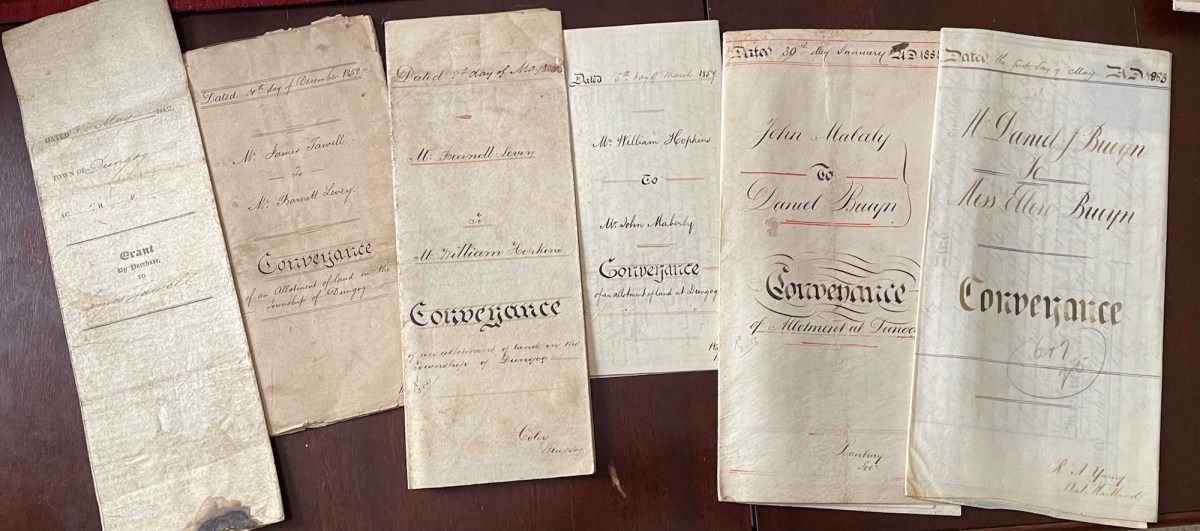

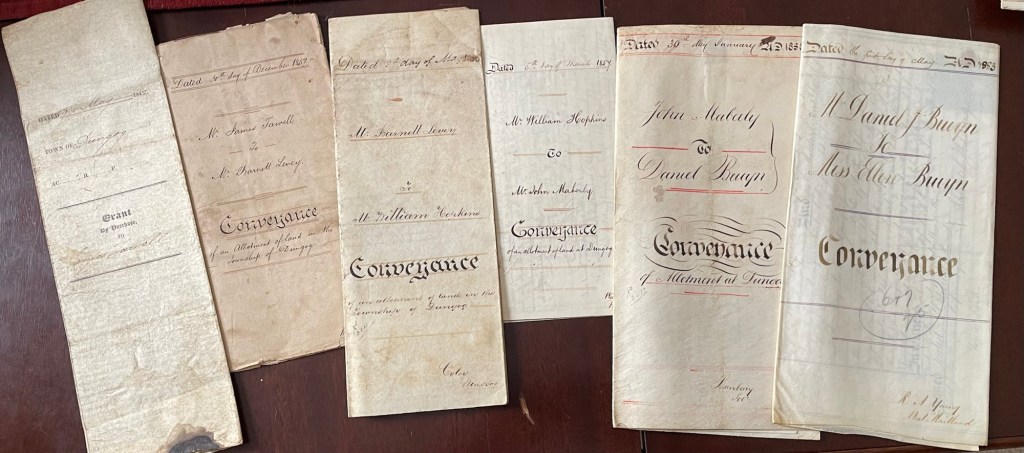

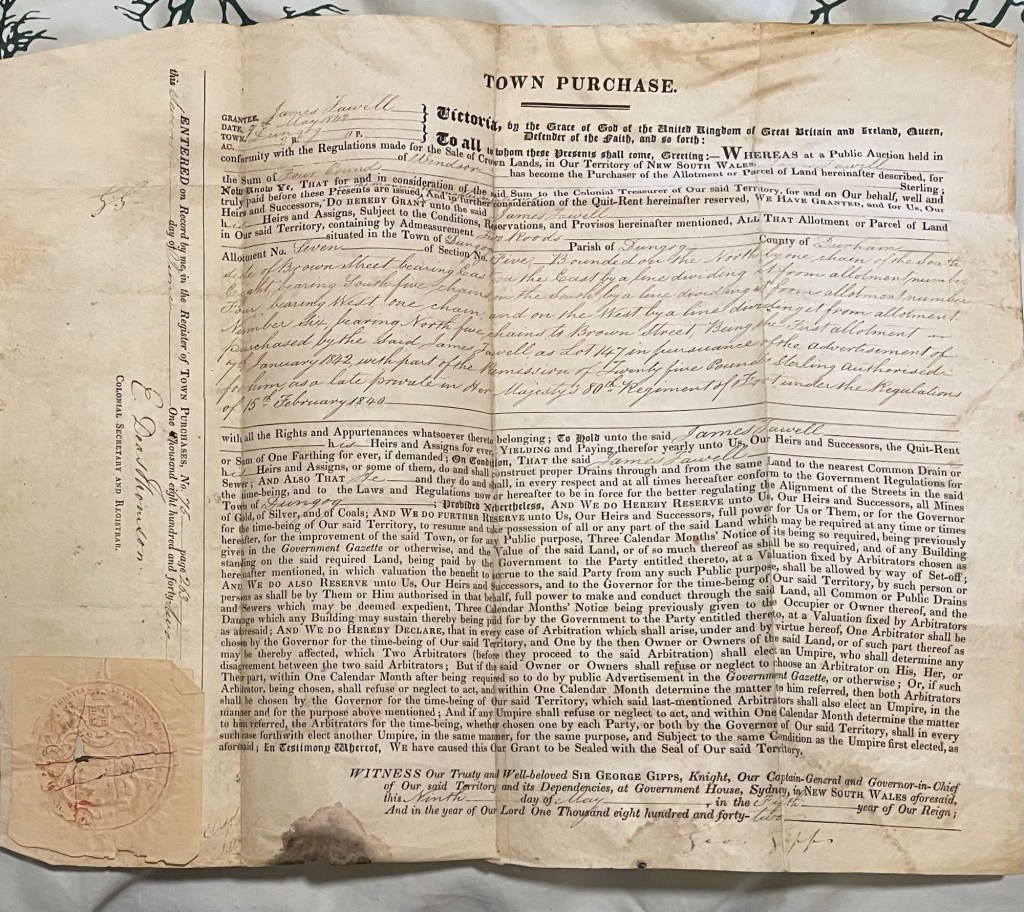

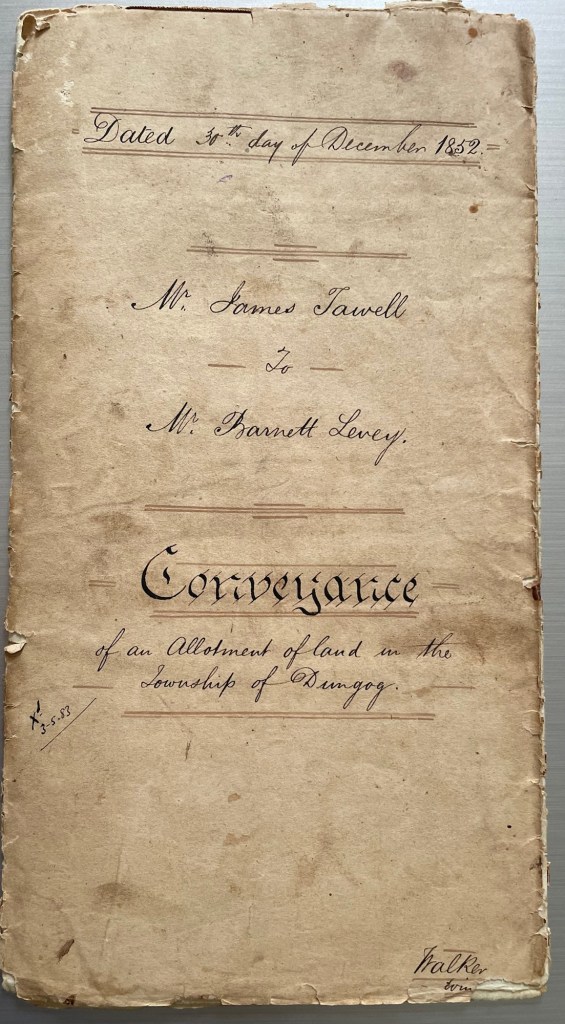

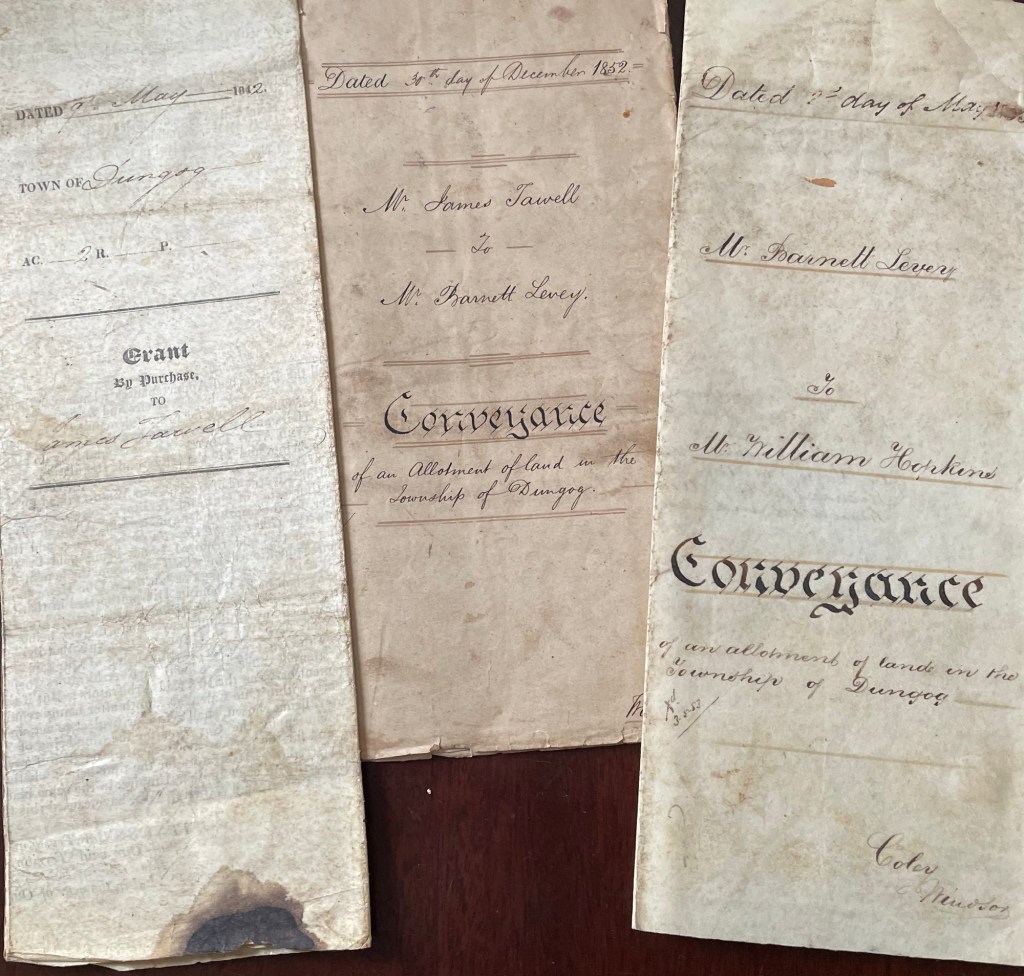

This post concludes the story of the land and house which Elizabeth and I purchased in Dungog a few years ago. I have traced the early landholders for this property (1848–1858), Daniel and Sarah Bruyn and their family (from 1858 to 1882) and then two of their children, Daniel Justin Bryan (d.1912) and his sister, Ellen Bruyn. In this blog, the story continues to the people who bought house in 1969, the Finneys.

(as the moving trolley attests!!)

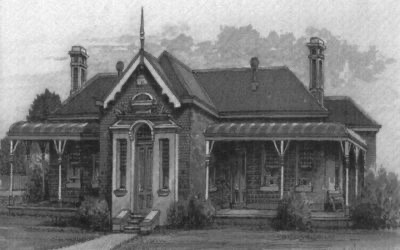

An interesting report in the Sydney Daily Telegraph of Tuesday 14 June 1927, p.18, entitled ARE WINTERS MILDER, quotes a “Mrs. [sic.] Ellen Bruyn, who has spent 71 years at Dungog” as declaring that “the winters of late years had be come milder, and the summers hotter, and drier”. It is interesting to see such an early observation relating to what we know now to be human-exacerbated climate change, as the average annual temperature is rising at a worrying level.

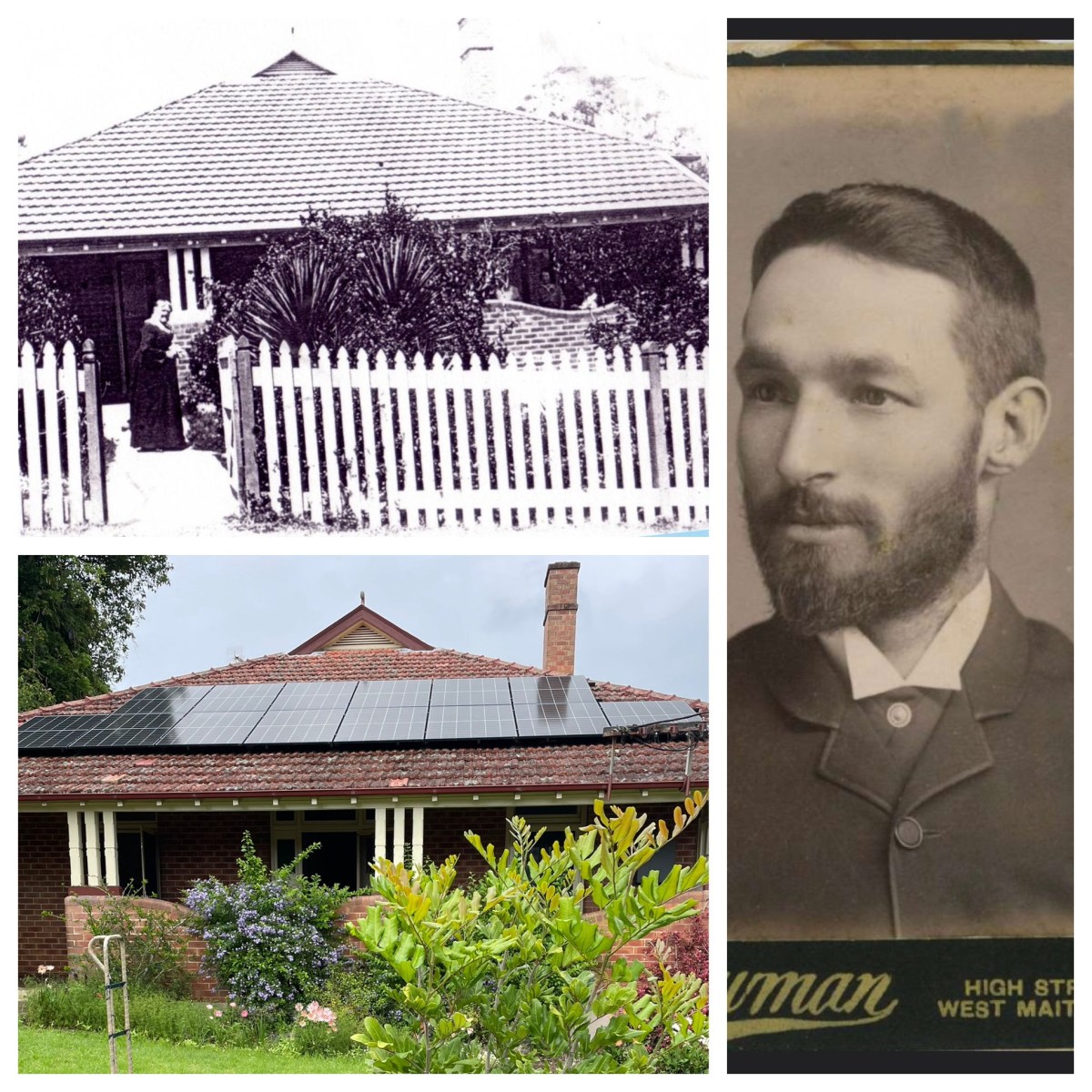

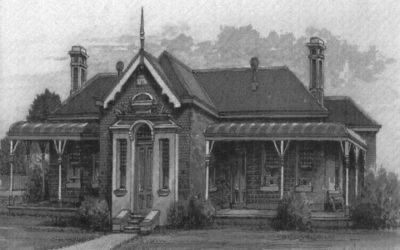

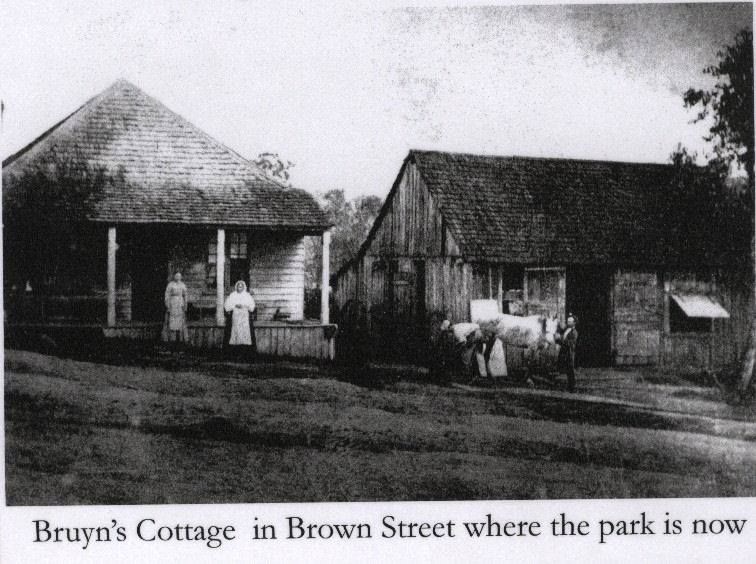

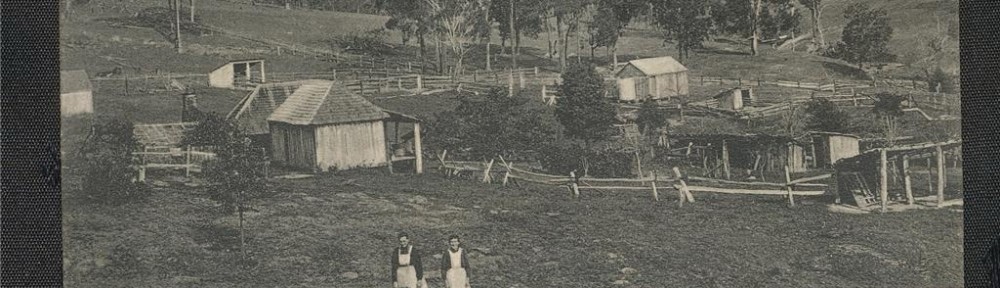

The Telegraph notes that “she quoted no thermometer readings to support her contention, but said she could speak with personal experience of the seasons, coupled with her observations of the less rigorous effects of recent winters upon vegetation in the gardens which adorn her residence.” Indeed: that would be the cottage garden at the front of her property, that is evident in the one photo of the house that is extant, as noted earlier.

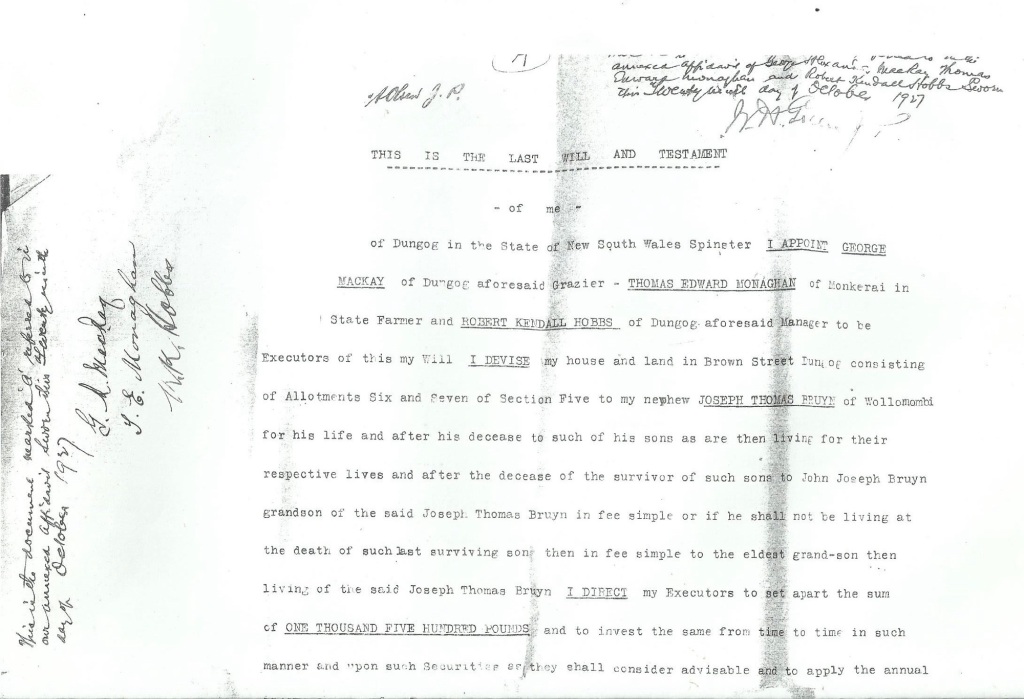

Ellen Bruyn’s Will

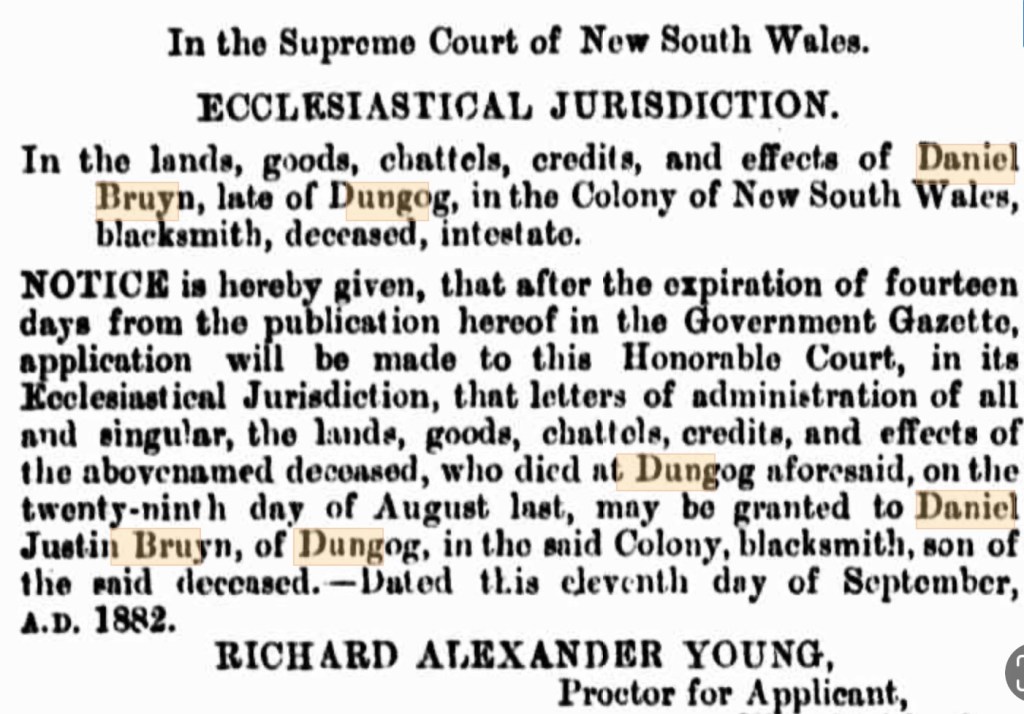

Ellen’s father had died intestate. Her property and goods were not to be caught in the same way; on 4 August 1925 Ellen Bruyn, then aged 85 years, made her Last Will and Testament, in which she appointed George Alexander Mackay, Thomas Edward Monaghan and Robert Kendall Hobbs the Executors. Just two years and two months later, on 2nd October 1927, Ellen Bruyn died. Probate was subsequently granted on 1 November 1927.

In an article in the Dungog Chronicle of Tuesday 4 October 1927, page 2, tribute was paid to Ellen Bruyn. “During her life-time Miss Bruyn was known far and wide for her benevolent nature and broad-minded charities. None that ever besought her help went away empty-handed.”

Reports of her estate indicate this extensive benevolence, with a lengthy report in the Sydney Morning Herald of Friday 4 Nov 1927, on p.6, providing details. The article is headed simply LATE MISS E. BRUYN. It notes that she left an estate “of the net value of £20,106”. A similar notice in the Maitland Weekly Mercury of 3 Nov 1927, p.5, reports that “the estate of the late Miss Ellen Bruyn, of Dungog, who died last month, aged 88, has been valued for probate purposes at £20,116”. The calculator provided by the Reserve Bank of Australia indicates that in 2023 this sum of money would be worth $1,932,438.79.

This was managed by a Trust established by the appointment of as George Alexander Mackay, Thomas Edward Monaghan and Robert Kendall Hobbs as Executors and Trustees in Ellen Bruyn’s 1925 will. Between 1932 and 1941, all three Trustees died; in February 1942 George Mackay, Donald Reay Mackay and Robert John Alison were appointed as “Trustees of the Will of the said Ellen Bruyn in the place of the deceased original Trustees”.

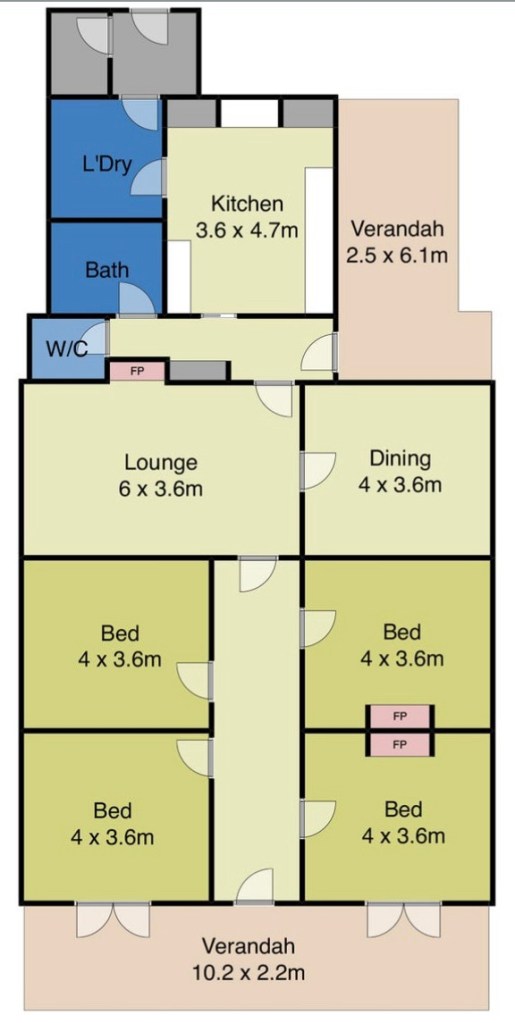

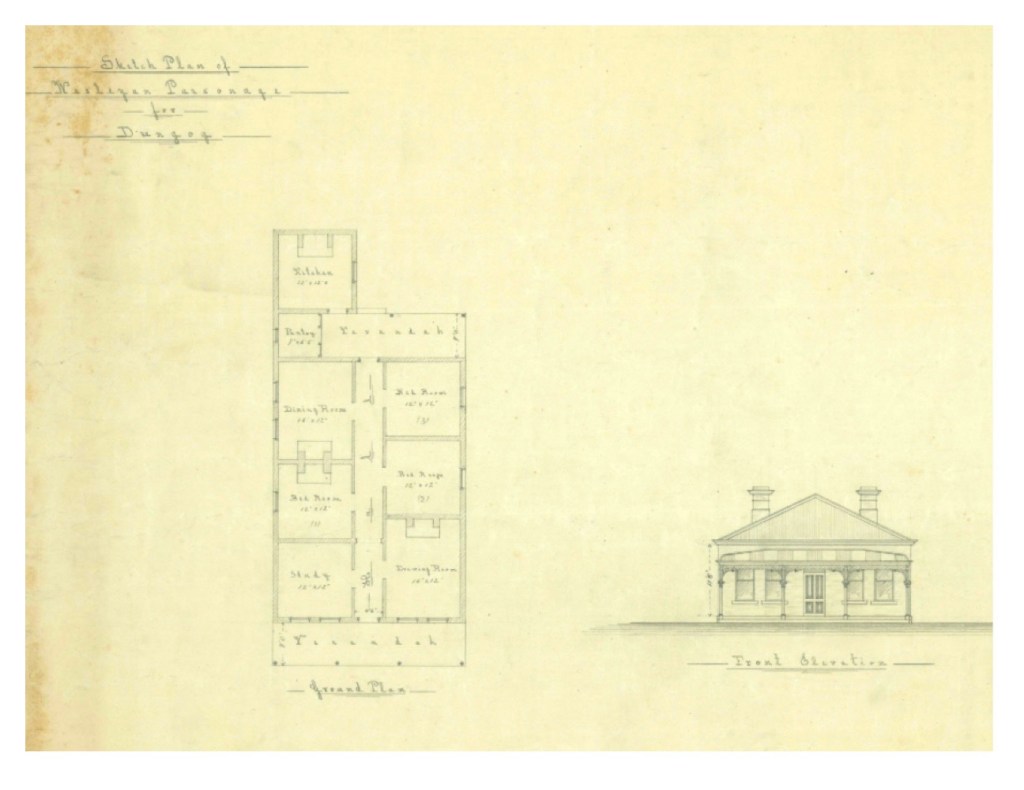

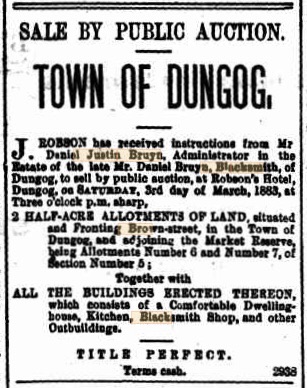

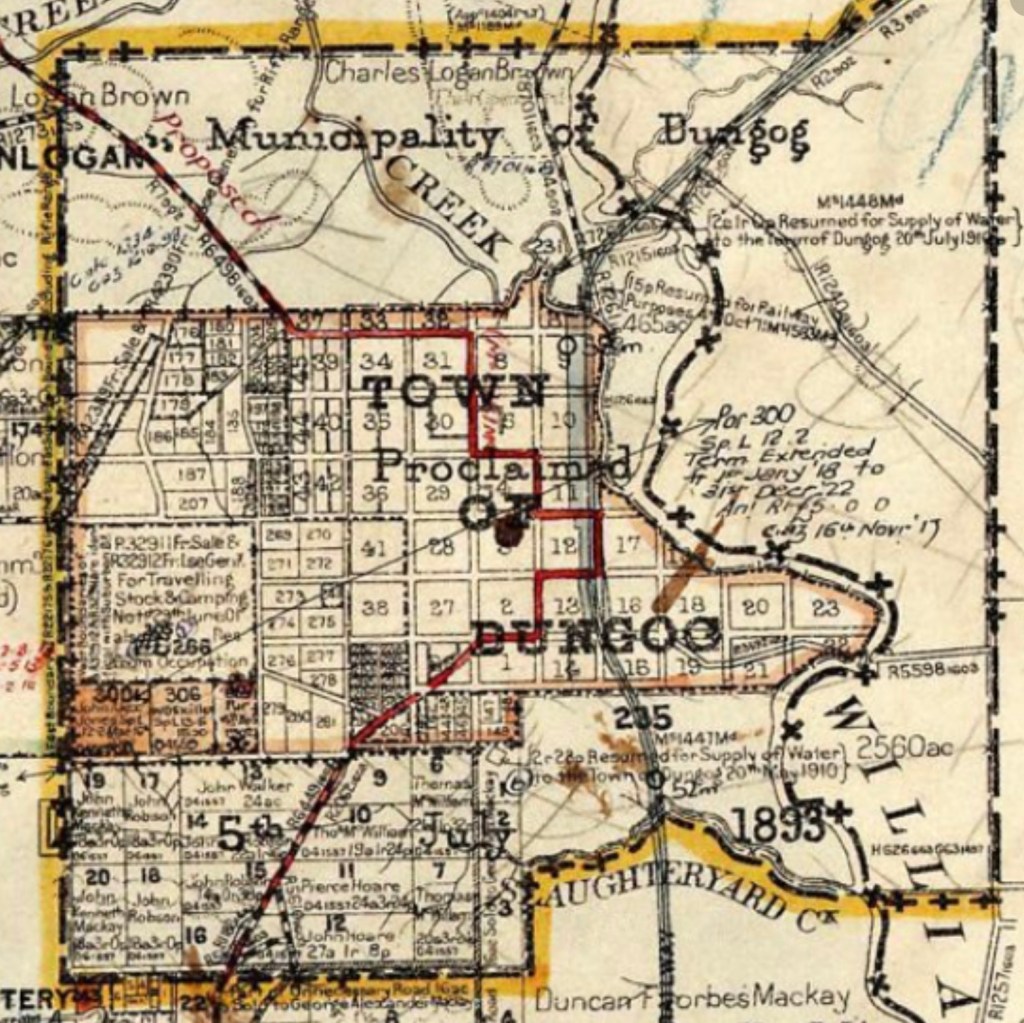

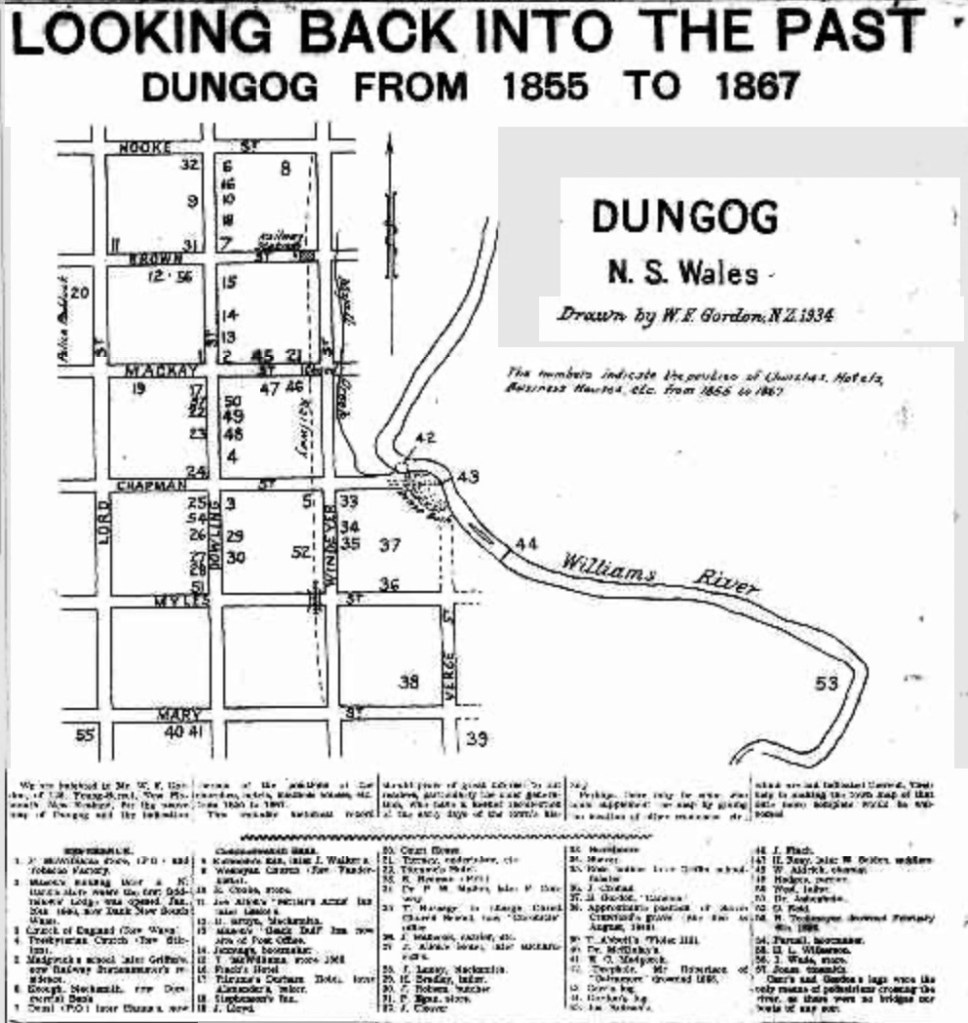

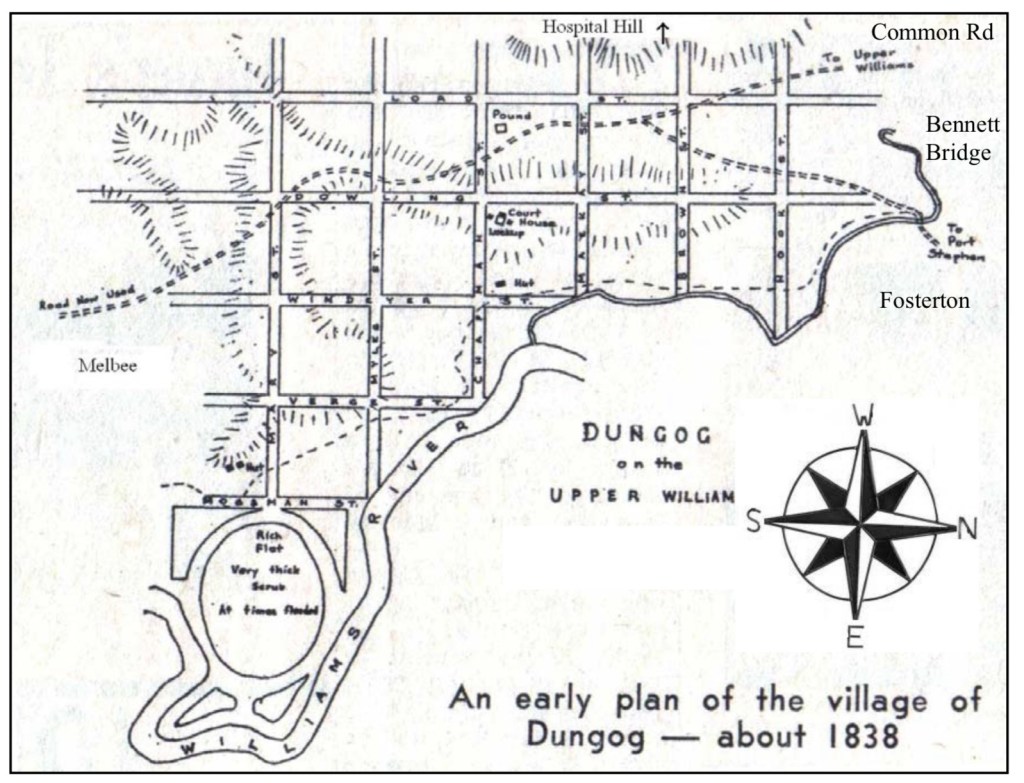

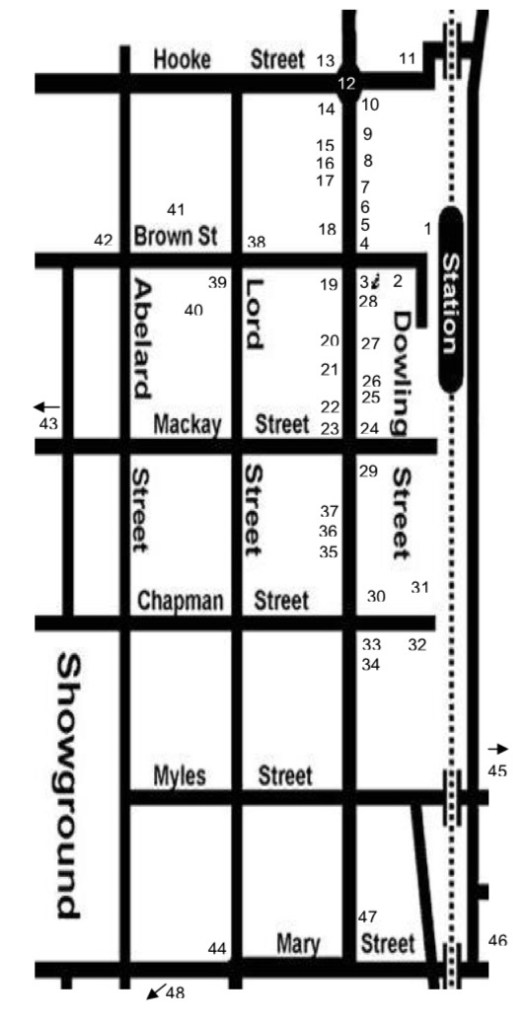

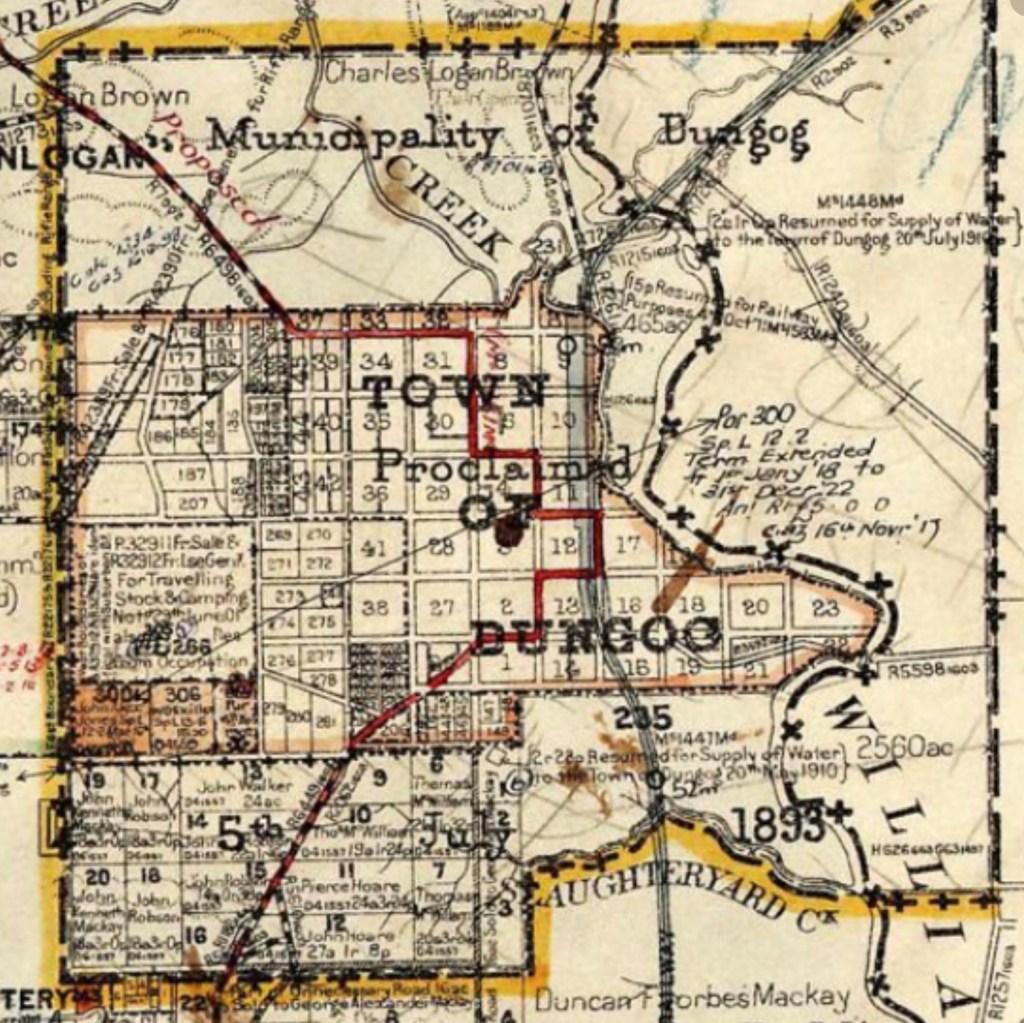

In this 1942 process, the components of the 1925 will forming the Trust were specified, in particular, as “£1000 secured by Memorandum of Mortgage 18 Dec 1928 for land at Heydon St Mosman; £1700 fixed deposit with Commercial Banking Company; £67.14.3 on account with Commercial Banking Company; Land in Brown Street Dungog on which is erected a dwelling house and other improvements being Lots 6 and 7 of Section 5 Town of Dungog; Vacant land in Mackay Street Dungog being Lots 4 and 5 Section 5 Town of Dungog”.

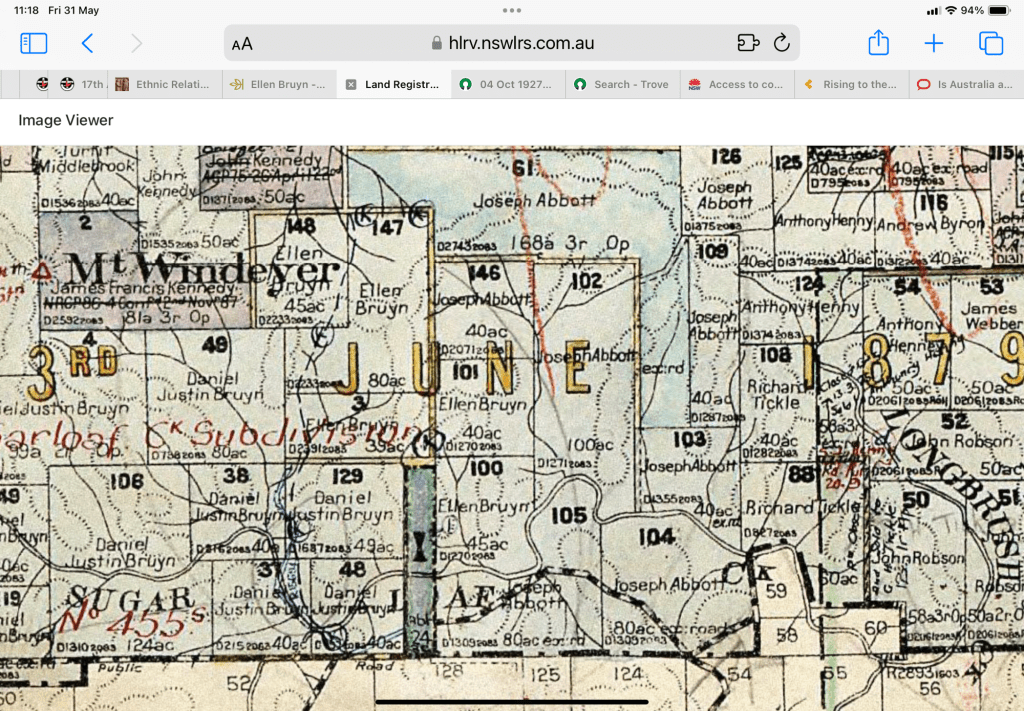

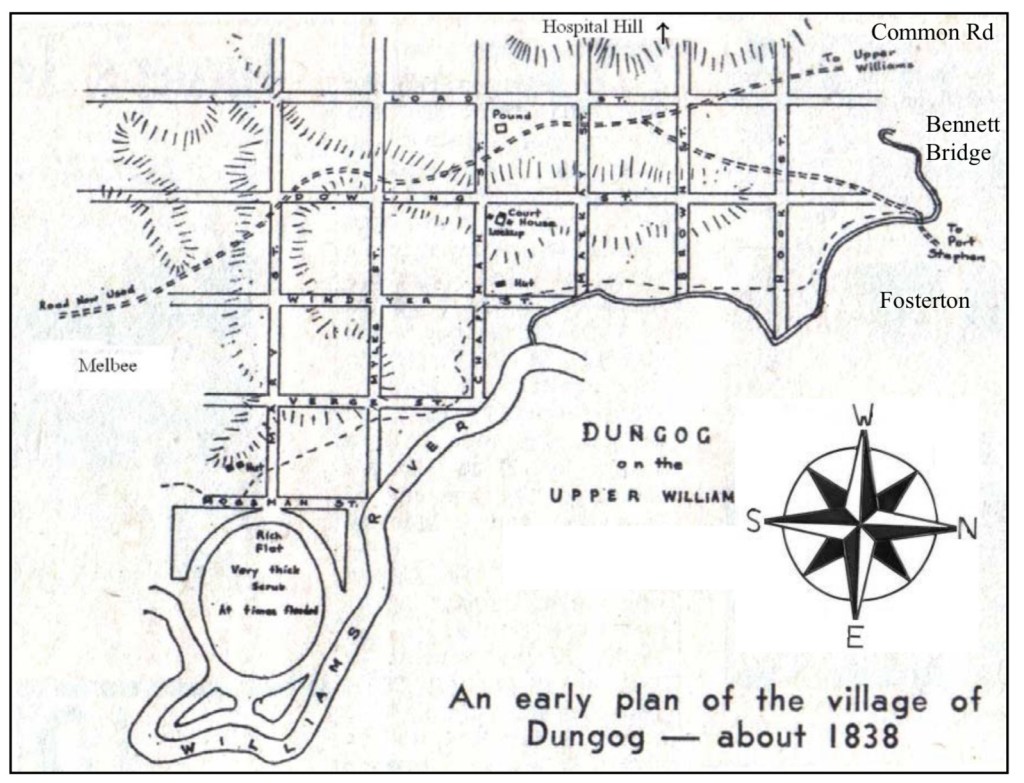

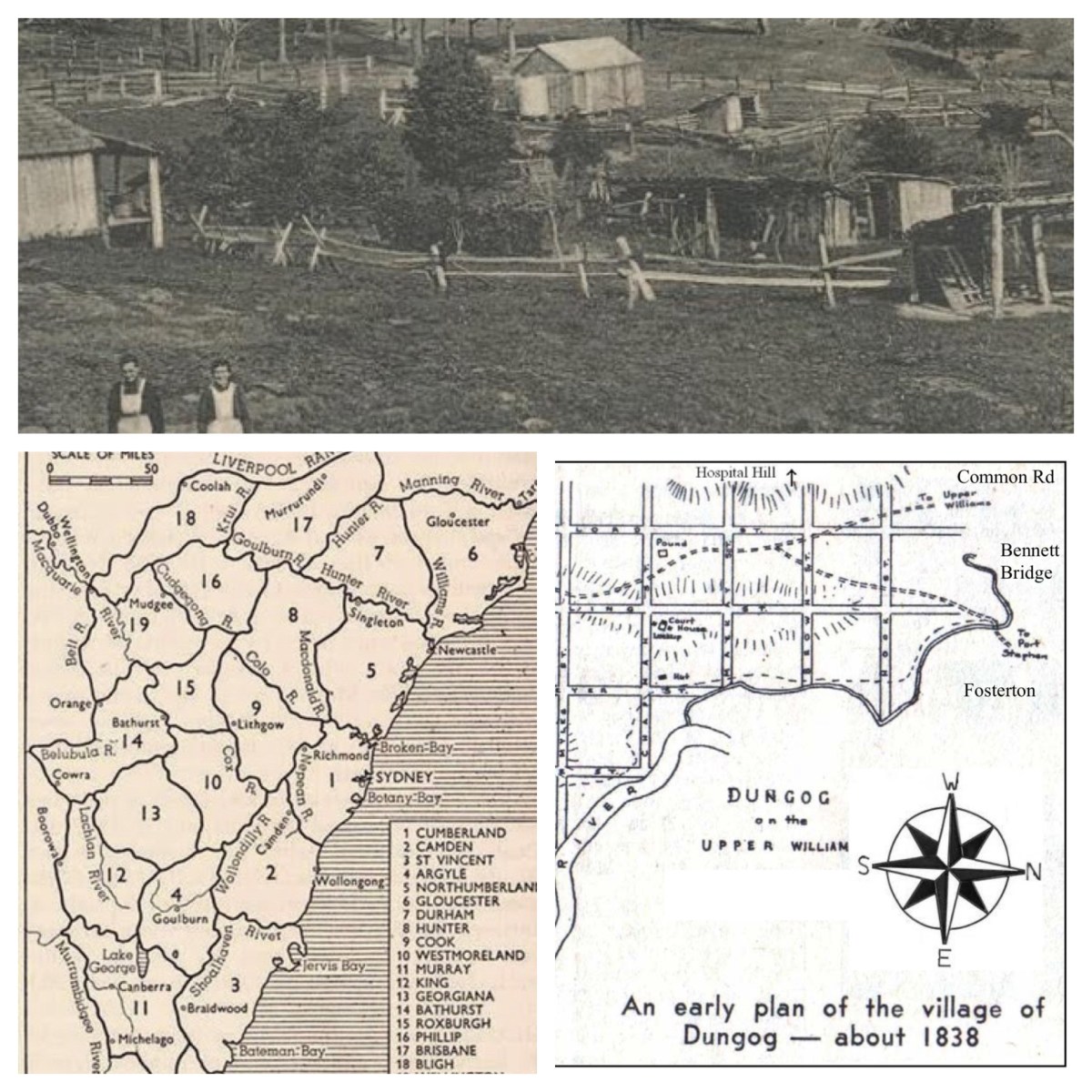

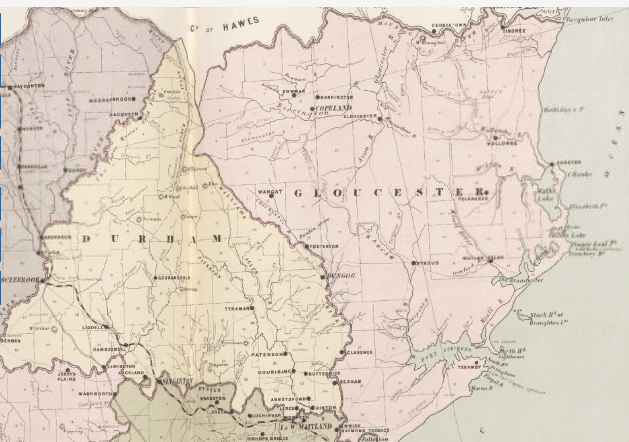

As far as the distribution of various elements of this estate was concerned, the SMH article provides specific details. It first notes that Ellen had “devised certain lands in Mackay-street, Dungog, to the local council, to be held by them in trust as a play and recreation ground for children; if, after a period of 20 years, the council did not think it advisable to use them as such, the lands were to be sold, and the net proceeds paid to the funds of the Roman Catholic Church at Dungog.” In 2024, the Council still maintains land on Mackay Street which is called Bruyn Park; it abuts the southern end of Jubilee Park, which runs along the western boundary of the Brown Street property once owned by the Bruyns.

Furthermore, Ellen took care to provide for her family, as “she devised certain real estate and £1500 to maintain it to her nephew, Joseph Thomas Bruyn, and his sons, £1500 each to her three sisters, Margaret Monaghan, Elizabeth Ann Cooke, and Sarah Malvina Lawless, and their daughters”.

perhaps within the last decade before her death?

The various charitable organisations that Ellen remembered in her will are signalled through this list of bequests: “£1000 to the Deaf and Dumb Institution conducted by the Dominican Nuns at Waratah, £500 to the Sisters of St. Joseph at Lochinvar, £500 to the Dr. Murray Catholic Orphanage at West Maitland, Waitara Foundling Home conducted by the Sisters of Mercy, £1000 to the Dungog Cottage Hospital”.

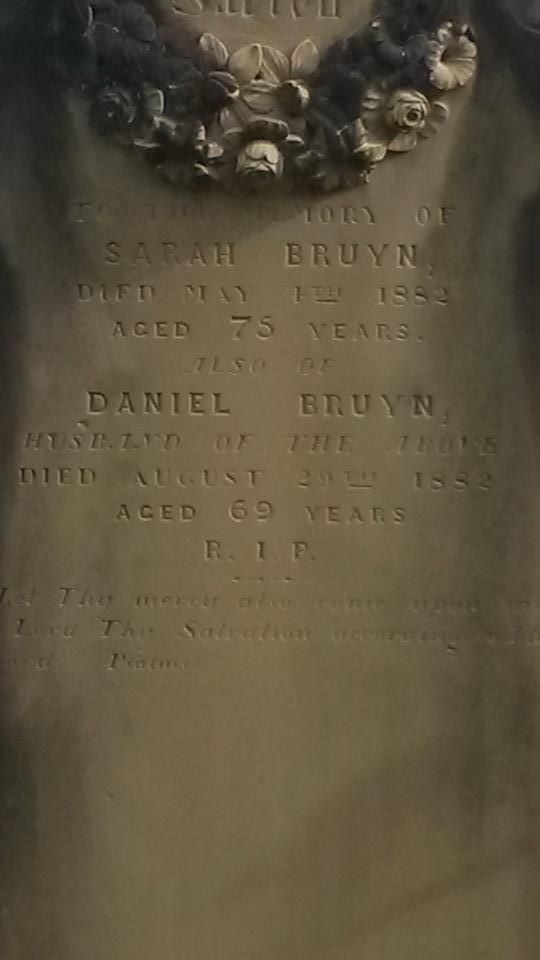

In addition, Ellen had directed that “the interest from the investment of £200 [was to be used] for the upkeep of the graves in the local cemetery of herself and relatives of the name of Bruyn for a period of 25 years from the date of her death; at the expiration of that period the £200 to be paid to the local Roman Catholic Church; £100 to the Roman Catholic curate at Dungog, and the residue of her estate to relatives and others”.

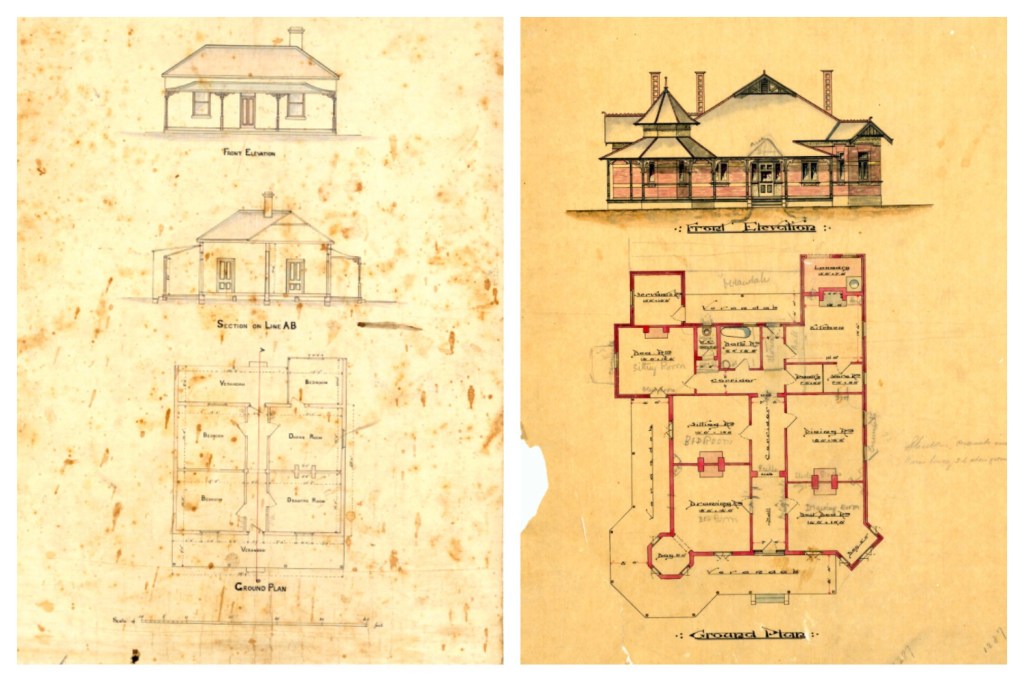

Dungog Cottage Hospital

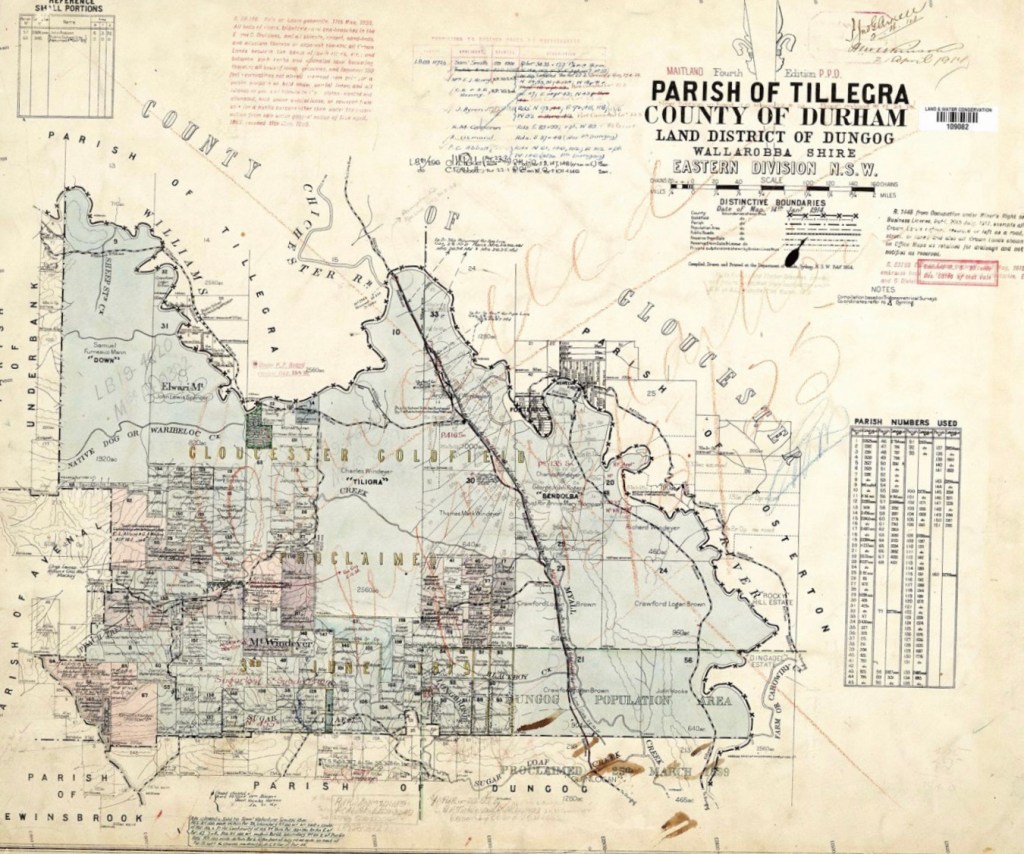

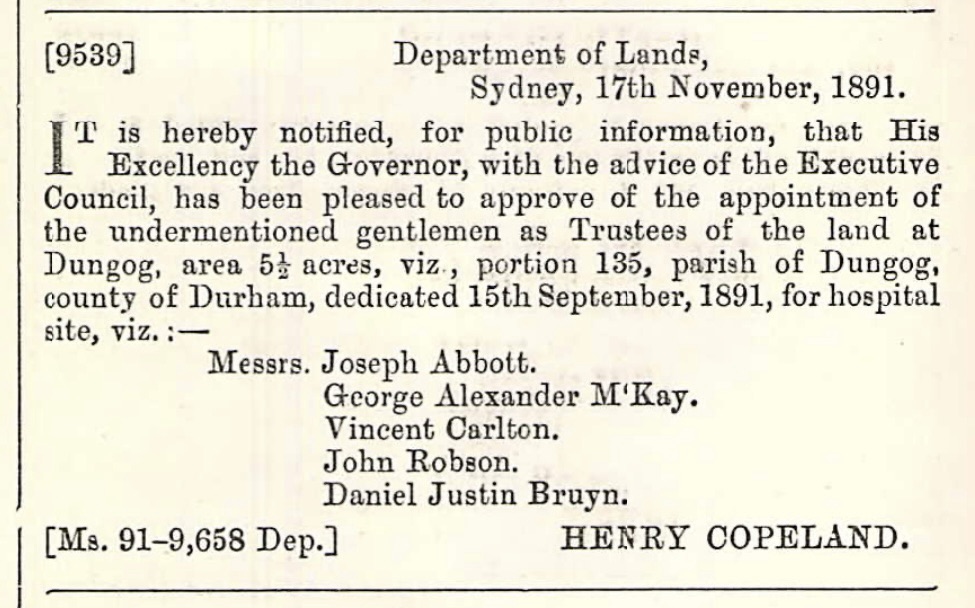

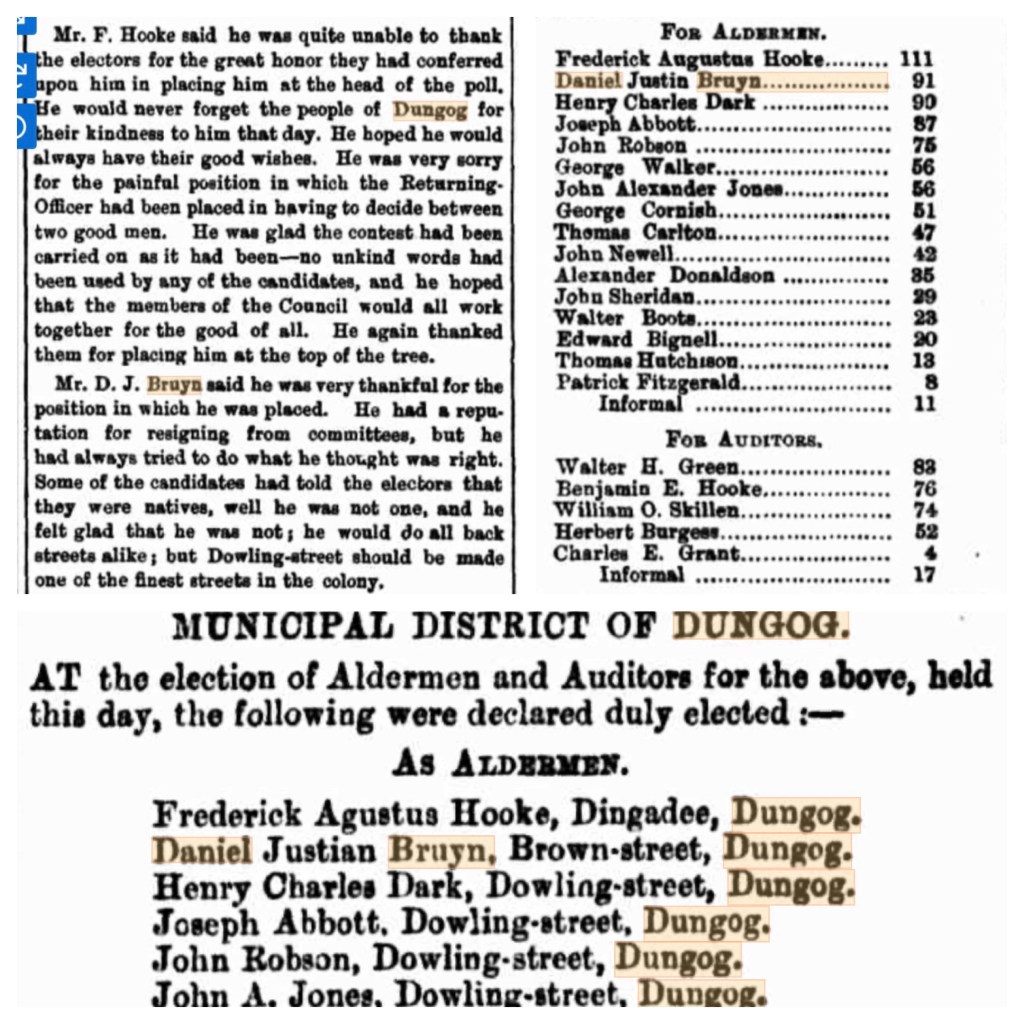

One significant matter identified in this will relates to the Dungog Hospital. Daniel had been appointed as one of the foundation members of the hospital committee in 1891. Ellen must have been actively involved in the years after Hospital Cottage was opened in 1892. One item in her will was that she bequeathed “£1000 to Dungog Hospital, the interest to be used for 20 years and then the principal to go to the committee” (Sydney Catholic Press, Thursday 13 October 1927, p.41).

Annual distributions in accordance with this bequest are reported in the Dungog Hospital reports over the two decades after Ellen’s death. The Dungog Chronicle reported that £17/10/- (three months interest) was paid in Sept 1929; however, over a period of years, there was no interest paid, occasioning legal communications regarding the accumulated amounts that had not been paid.

From 1939, interest was paid more regularly: £71/3/10 in Aug 1939, £43/-/- in May 1940, £7/12/- and £4/15/- in Sept 1941, £44/5/9 and £136/6 in Sept 1942, as well as “an advance of subsidy for £28/6/8 and a special grant of £1/15/-“, followed by £10/1/9 in Oct 1942, £8/5/- in Feb 1943, “the usual subsidy of £28/6/8 … and a further amount of £51/6/8, being arrears of subsidy for the year commencing 1/7/42”. This presumably satisfied the accumulated amount due that had not been paid in earlier years.

The Hospital then received £45/4/5 in Sept 1943, £28/-/- in Sept 1944, £27/15/9 in May 1945, £23/18/9 in Oct 1945, £10/1/9 in June 1946, £47/-/- in Aug 1946, £31/16/9 in Feb 1947, £16/14/- in April 1947, and £23/9/6 in Aug 1947. In that month, the Hospital Board was advised that “the 20-year period of this investment in house properly at Mosman expires on 2/10/1947, and the matter has been placed in the hands of the Hospital’s Honorary Solicitors, Messrs. Borthwick and Wilson”.

Nevertheless, £11/2/4 was received in Jan 1948, £12/2/10 in June 1948, and £12/7/9 in July 1948. The income over the years had been generated through an investment in a property in Mosman; the property now needed extensive repairs, so at the Jan 1949 meeting, “it was moved by Messrs. Scott and Irwin that a copy of the Commission’s letter be forwarded to Messrs. Borthwick and Wilson and that they be requested to instruct solicitors for the Bruyn Trustees to take necessary action as set out in the Commission’s letter”.

A further £12/7/9 was paid in Sept 1949, while “Hospital’s Honorary Solicitors have been requested to instruct the Solicitors for the Bruyn Trustees to take necessary steps to obtain consent of the Moratorium Court to sell the property prior to its being offered for auction sale”.

In July 1951, the Secretary advised the Board that “a cheque for £111/1/3 had been received through Messrs Enright Son and Atkin, being rent received from Messrs. Richardson & Wrench Ltd., from 2/7/1948 to 18/6/1951, less collection charges, exchange, repairs, and rates”.

In July 1953, “£52/13/5, being rent collected in connection with the Bruyn Bequest”, was received. This was the last payment that has been found through reports accessed in Trove’s collection of newspapers.

The Sale of Brown Street

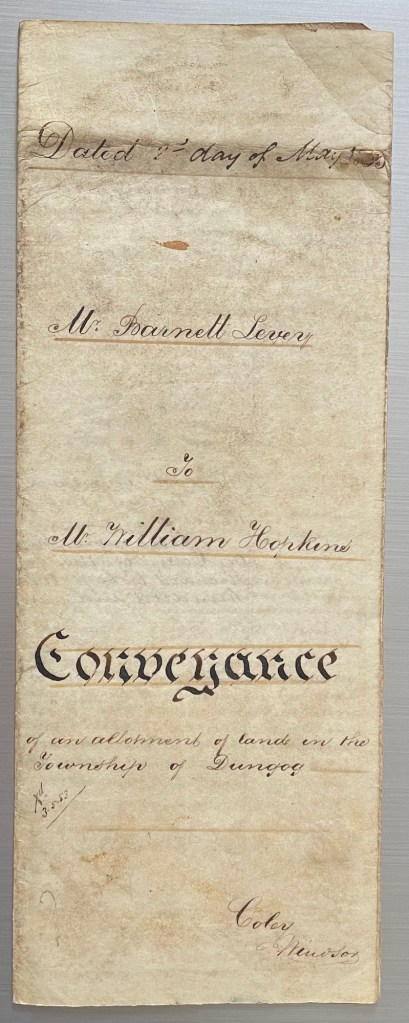

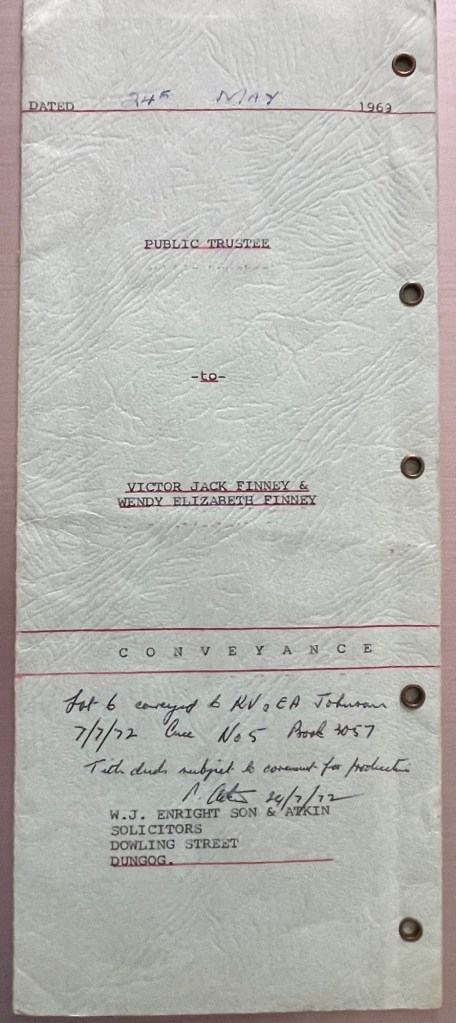

The last act of the Trustees of the Ellen Bruyn Bequest, in 1969, was to place the property on Brown Street up for sale. The documentation received relating to the Brown Street property for the period from 1927 to 1969 concludes with a document that notes the various changes in personnel in those Trustees, and a 1969 Conveyance. It is most likely that the property was rented out for this period of time, thereby bringing in a regular income to the Trust.

On 30 June 1967, George Dark was appointed Trustee in place of George Mackay and Donald Reay Mackay, joining Robert John Alison as continuing Trustee. Then, on 8 April 1968, these Trustees appointed the Public Trustee “to accept the trusts of the will accordingly”. The trusts were comprised of “Land in Brown Street, Dungog on which is erected a dwelling house and other improvements being Lots 6 and 7 of Section 5 Town of Dungog; Special Bonds Series “I” due September 1970 $1,600 Treasury Bonds held by the Commercial Banking Co.; Commonwealth Treasury Bonds August 1975 — 5 — $1,400; Current Account Commercial Banking Co. of Sydney Limited Dungog — $13.15”.

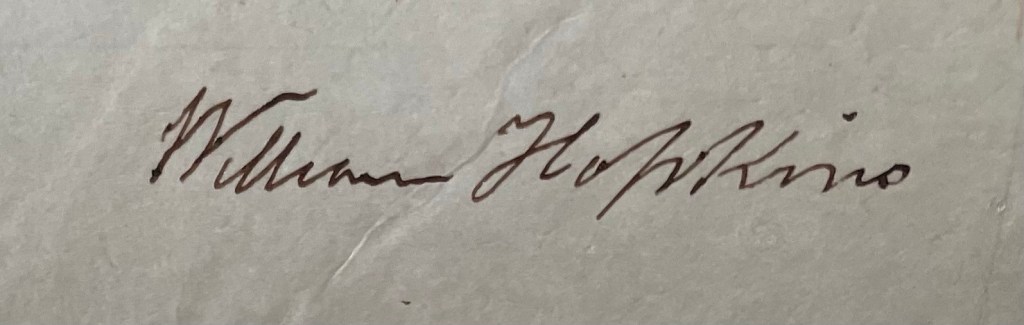

And so it was that in 1969, Victor Jack Finney and Wendy Elizabeth Finney purchased this property. In a Conveyance dated 24th May 1969, between “the Public Trustee as Trustee of the will of Ellen Bruyn, late of Dungog, Spinster deceased, and Victor Jack Finney of Dungog, Evaporator Operator, and Wendy Elizabeth Finney of Dungog, his wife”, Lot No. Seven of Section No. Five and Lot No. Six of Section No. Five were purchased for three thousand five hundred dollars. A new set of owners would, in time, move into the house and begin a new era.

For earlier blogs, see