My ancestor Nathan Taylor arrived in the colony of New South Wales on the ship Adelaide 173 years ago, on 24 December 1849. He had been sent to the Colony as a convict. For reasons that are explained below, Nathan was granted a Ticket of Leave just six days after his arrival in the Colony, on 30 December 1849—173 years ago today.

Nathan was my great-great-great-great-grandfather on my mother’s paternal line. He is the fifth reason that I was born in Sydney (along with Joseph Pritchard, Bridget Ormsby, and James Jackson, all from my father’s line, and Elizabeth Lawrence and her daughter Louisa, from my mother’s line.)

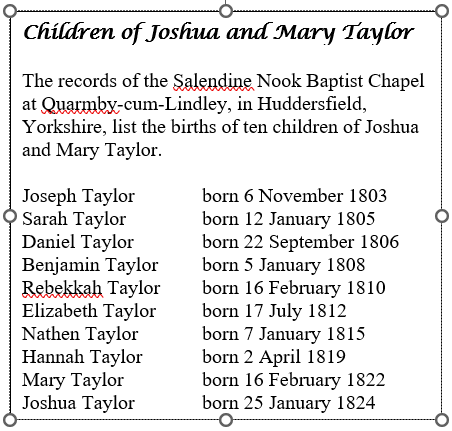

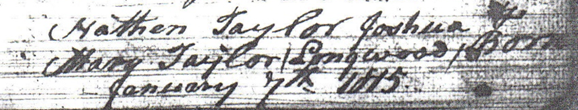

Nathan Taylor was born on 7 January 1815, the seventh of ten children born to Joshua and Mary Taylor, of Longwood, a village near Huddersfield in Yorkshire. Joshua and Mary were “non-conformists”, who attended the Salendine Nook Baptist Chapel at Quarmby-cum-Lindsey, a village to the west of Huddersfield,

in West Yorkshire.

This Chapel had grown out of the meeting of a group of Scottish dissenters, who came to England seeking religious freedom just over a century before. A meetinghouse was built between 1739 and 1743, and worship has continued there for nearly three centuries.

for the birth of “Nathan Taylor”, to Joshua and Mary Taylor

The Chapel register contains the records for the birth of ten children to Joshua and Mary, over the period of 1803 to 1824 (see below). All ten children have biblical names, reflecting the strong religious convictions of these Baptist parents. (Notice the spelling “Nathen”.)

Marriage and children

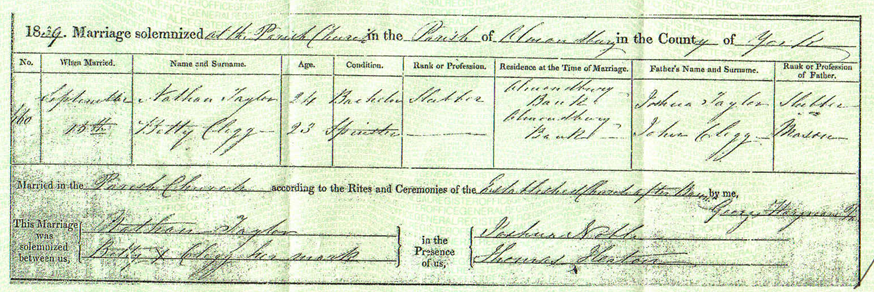

At the age of 24, Nathan Taylor married Elizabeth (Betty) Clegg, the daughter of John and Betty Clegg, at Almondbury, a village to the south-east of Huddersfield. The marriage took place on 15 September 1839; it was conducted by the vicar, George Hargreaves, in the Parish Church, and their place of residence is listed as Almondbury Bank. It seems that the Clegg family were members of the established Church of England.

of Nathan Taylor and Betty Clegg.

A son, William, was born in 1839. (Perhaps he was the reason that Nathan and Elizabeth married?) Sadly, William later would die by drowning at the age of 18. Then a daughter, Mary, was born in 1841.

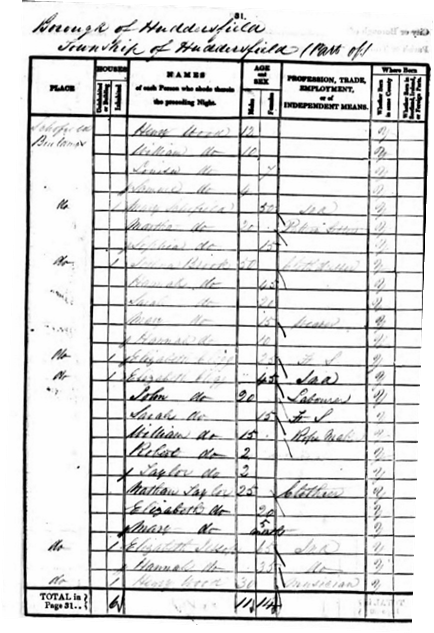

The returns for the 1841 Census for the division of Upper Agbrigg (Agbridge) in Huddersfield, Yorkshire (pictured below) list a family of Nathan Taylor, 25, Clothier, his wife Elizabeth, 20, a daughter, Mary, aged 5 months, living in Schofield Lane in the township of Huddersfield.

There is no mention of a son, William, in this record. However, it does appear to be the correct Taylor family, for in the building next door in Schofield Lane, there is recorded a family which is most likely to be the family of origin for Elizabeth (Betty).

This family comprised the mother, Elizabeth Clegg, aged 45, and children John, 20, Sarah, 15, William, 15, Robert, 2, and Taylor, 2. Elizabeth’s father, John Clegg, would appear to have died by the time of the Census.

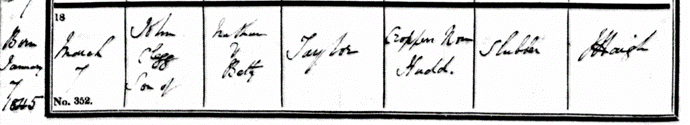

A second son, John, was born to Nathan and Betty in Huddersfield on 7 January 1845, and then a further son, Ben (presumably short for Benjamin) was born on 19 January 1847. The record of baptisms in the parish of Huddersfield (see below) indicate that John and Ben were both baptised on 7 March 1847, by the parish priest, Rev. J. Haigh.

John was given the maiden name of his mother, Clegg, as his middle name, and he consistently appears in official records as John Clegg Taylor. (That’s a neat connection for me, as my middle name is Taylor, my mother’s maiden name—John Taylor Squires, the same pattern as my gtgtgtgtgrandfather, Nathan Clegg Taylor!)

The surname Clegg appears to have a local origin in northern England. It appears in earlier records from north Lancashire, initially with a prominent family at Clegg Hall at Rochdale, about 20 miles from Huddersfield. The name is most densely concentrated today in Oldham (near Rochdale) and Holdfirth (just south of Huddersfield). See https://www.jacksoneditorial.co.uk/yorkshire-surnames/#clegg

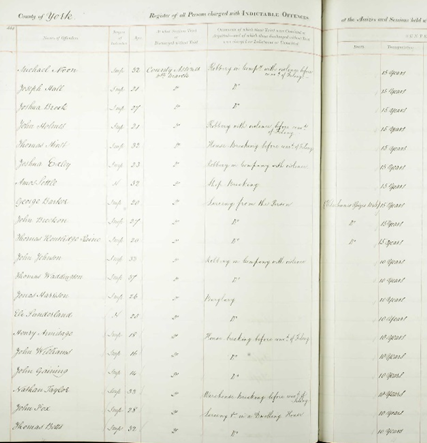

Active as a Chartist

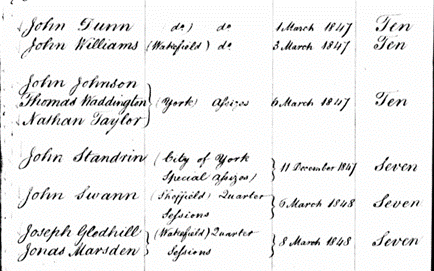

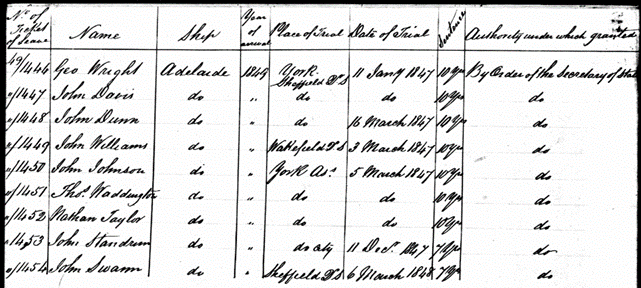

However, within two years, the family, was torn apart. On 6 March 1847, at the age of 33, Nathan Taylor was tried at the York Assizes, on the charge of “Warehouse breaking”. He was sentenced to ten years imprisonment. Also tried with him that day were John Johnson, 33, and Thomas Waddington, 37, both of whom received the same sentence for their crime of “Robbery in company with violence”. (See the court records below.)

Intriguingly, on the day immediately after this (as noted above), the two sons of Nathan and Betty, John and Ben, were baptised in Huddersfield!

John Johnson, Thomas Waddington, and Nathan Taylor were amongst 302 convicted men who subsequently were transported to the colony of New South Wales on board the ship Adelaide. They were Chartists.

A whole group of a Chartists had been sentenced to ten years, and then sent to the Colony, under special arrangements (as detailed below).

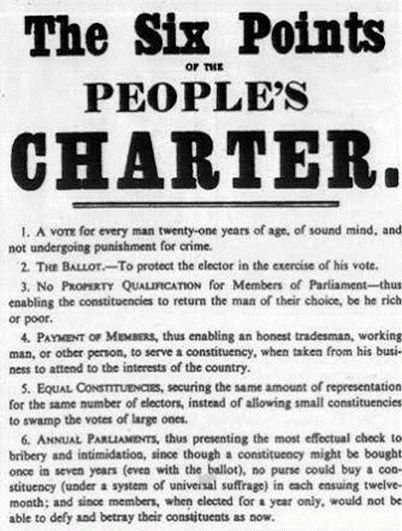

Chartism was a movement in Britain during the period of 1838 to 1857 which was initiated by the promotion of a Peoples Charter in 1838. The Chartists held mass protest meetings and collected petitions which were presented to Parliament. There were protest activities by Chartists in many English cities. It was especially strong in the northern regions of England—precisely where Nathan Taylor was living.

The Chartists were seeking a series of reforms to the political system (reforms which were eventually adopted, and which are taken for granted in modern democracies)—the vote for all adult males, the use of a secret ballot, the removal of a requirement for property ownership by Members of Parliament, payment of Members of Parliament, electorates with equal numbers of electors, and annual Parliamentary elections.

The arrangement concerning convicted Chartists was that such men would be sentenced to ten years and then sent to the colonies, and if they exhibited “exemplary” behaviour on the voyage to the south, they would be pardoned on arrival. This appears to have been what was done in relation to Nathan Taylor. See https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/A_Guide_to_Researching_Political_Prisoners

Transported on the Adelaide

The Adelaide departed London on 17 August 1849, with John Johnson, Thomas Waddington and Nathan Taylor amongst the 302 convicted men who were on board. The Adelaide was a wooden ship which had been built in 1832 and was used three times as a convict transport (1849, to New South Wales; 1855, to Western Australia; and 1863-64, to Gibraltar.)

See https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/adelaide

An extract from the ship’s record, listing the convicts on board, including Nathan Taylor.

The Sydney Morning Herald 30 November 1849 published this report from England:

Portland, England. On Monday morning, a party of 132 well-conducted convicts left the convict establishment, and were embarked for Port Phillip in the ship Adelaide, which had been some days waiting for them. We understand that, upon arriving in the colony (should their conduct on board be proved exemplary), they will each be presented with a ticket of leave which will entitle them to work for themselves, being comparatively speaking, free.

In addition to the above, there were 170 selected from Pentonville, the hulks, and Parkhurst prisons, who will be allowed a similar indulgence. A guard, composed of 50 soldiers, will accompany them on the voyage, selected from her Majesty’s 63rd, 65th, and 99th regiments of foot. There is an experienced surgeon on board, who has the care and management of the convicts, and also a religious instructor. The Adelaide was still in the roads on Tuesday night, waiting for a fair wind. See https://www.jenwilletts.com/convict_ship_adelaide_1849.htm

The last convict ship

The Adelaide duly arrived in Hobart on 29th November, where 40 men were disembarked. The ship sailed on to Port Phillip, with the intention of offloading more men, but it was refused entry and sailed on northbound to Port Jackson.

The settlement at Port Phillip had received around 1,750 convicts sent as political prisoners (often referred to as “Exiles”) in the years 1844 to 1849, but resistance to their presence grew in those years and was strong by 1849, as it attested by the failure to offload all the men on the Adelaide.

The Adelaide eventually arrived in Port Jackson on 24 December 1849, after a journey on the high seas that had lasted for 129 days. The Adelaide was the last convict ship to arrive in Sydney. Transportation, which began in 1788, had ended in Moreton Bay (Brisbane) in 1839, but continued to Van Diemen’s Land until 1853, and to Western Australia until 1868.

Arrival in the colonies

Once the ship had docked in Port Jackson, three prisoners were sent to the Hospital at Sydney and three were sent to Cockatoo Island on the recommendation of the Surgeon. The remaining prisoners on board were discharged daily as they were hired, commencing ship on 31 December 1849 and concluding on 9 January 1850.

The relevant page of the ship’s record relating to Nathan Taylor

Ticket of Leave

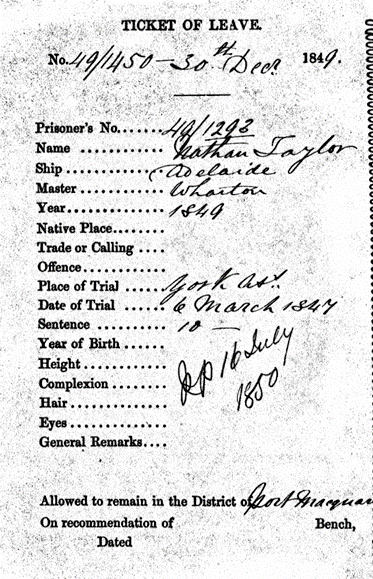

Within a week of arrival in the colony, the prisoners on board the Adelaide were given Tickets of Leave, by order of the Secretary of State. Nathan Taylor’s Ticket of Leave, number 49/1450, was granted on 30 December 1849 (see below).

Nathan was permitted to remain “in the district of Port Macquarie”, which stretched well north of Sydney, and included the northern rivers region (which is where later records place Nathan). From this point on, Nathan Taylor was once again a free man.

The journey of Betty and children on the Ramillies

His wife, Elizabeth, and two children, William and John, were still in Yorkshire. (Mary appears to have died by this time.) However, records indicate that Elizabeth and her two sons sailed to New South Wales on the ship Ramillies, which departed from Plymouth on 18 April 1850.

The Ramillies was a 757 ton barque ship which had been built at Sunderland in 1845. The Hobart Courier reported on 24 July 1850:

Arrived the ship Ramillies, 757 tons. [Master] Carvell, from Plymouth 18th April, with 271 bounty emigrants, and the following cabin passengers — Peter Nicholls, Esq., James Murphy, Esq., Mr. and Mrs. Linnell, one servant; Surgeon Superintendant, Dr. Fletcher. Cargo general. Health good, a few cases excepted. The ship’s records report that there were 97 women, 84 men, 31 boys and 23 girls who travelled in Steerage as Bounty Emigrants.

See http://marinersandships.com.au/1850/08/013ram.htm

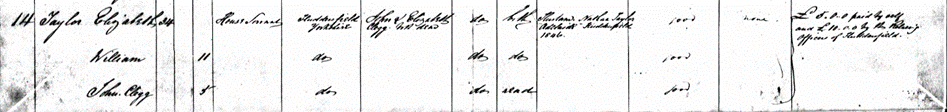

The records of the Assisted Immigrants Passenger Lists identify the passengers by name. These records include specific reference to Elizabeth Taylor, 34, House Servant, of Huddersfield, Yorkshire, daughter of John and Elizabeth Clegg, “both dead”; along with William, 11, and John Clegg, 5, as arrivals on board the ship Ramillies (see below).

In the column “Relations in the Colony” is written, “Husband Nathan Taylor, ‘Adelaide’, Huddersfield, 1847, present address Unknown” (presumably the year refers to the time of Nathan’s activity which caused his arrest). Elizabeth, William and John were all in a good state of “bodily health, strength and usefulness”, and they had no complaints about their treatment on the ship.

An additional annotation reports “£5.0.0 paid by self and £10.0.0 paid by the Relieving Officers of Huddersfield”. Relieving Officers were appointed under the Poor Law Act of 1834, to oversee the administration of relief to the poor. It appears that the system was such that Elizabeth was able to petition to be reunited with her husband in the Colony.

Life together in the colony

The Ramillies duly arrived at Port Jackson on 11 August 1850, at which time Elizabeth made enquiries regarding the whereabouts of her husband, Nathan, and ultimately Nathan was reunited with his wife and children.

Indeed, records indicate that, over the next decade, a further five children, three daughters and two sons, were born to Elizabeth and Nathan, all in the Richmond River region in northern New South Wales. Sadly, one of those sons, Charles, died in 1860, during the first year of his life; whilst William, the firstborn, had died by drowning three years earlier, in 1857.

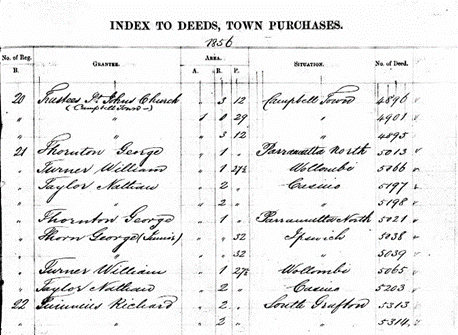

Nathan himself appears to have lived a full life in the Northern Rivers Region, where he was employed initially as a Labourer. In 1856 he bought land in East Ballina, and in 1862 additional land in Casino (see record below).

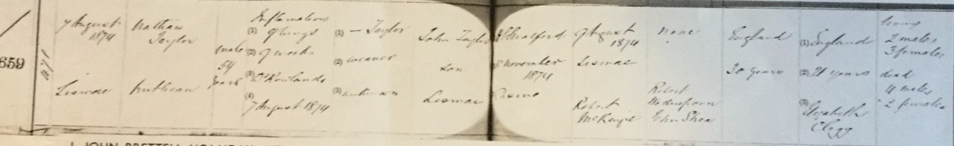

Nathan was appointed as a Foot Constable in the Northern Police District, on 22 November 1858. Police records describe him as 5’8” tall, with light brown hair, brown/grey eyes, and a sallow complexion. He worked as a Constable for six years (Number 782) before resigning on 31 October 1864.

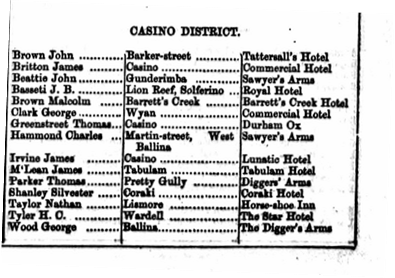

After this, Nathan conducted a store and then was licensed as the publican of the “Horse Shoe Inn” in Lismore in the 1870s. He later bought the warehouse and hotel of Henry Brown, which he kept until his death.

The final years

Elizabeth died of apoplexy in Lismore on 25 June 1871, and Nathan married Caroline Penelope Browning three years later on 28 May 1874, in the Lismore Presbyterian Church. Caroline had been married to Henry Johnson Brown in 1846 and had given birth to fourteen children over the period of 1847 to 1867. Henry died a year later, in 1868, aged on 47 years.

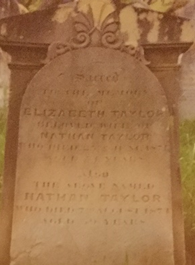

Soon after this marriage to Caroline, Nathan’s lungs became inflamed, and he died just ten weeks after his marriage, in Lismore, on 7 August 1874. He is buried with Elizabeth in the North Lismore Cemetery. (See his death certificate, above, and their tombstone, below.) Caroline subsequently married, for the third time, in 1878, and lived on until 1894.

My line of descent from Nathan and Betty Taylor is through their second son, John Clegg Taylor (1846–1878), who married Eliza Jane Wotherspoon; their son Herbert Taylor (1871–1936), who married Ada May Lee; and their son Jack Leslie Taylor (1897–1968), who married Hazel May Barron; they are the parents of my mother.

*****

See also