A reflection given by the Rev. Dr John Squires at Dungog Uniting Church on Sunday 18 January 2026.

In just over a week, on 26 January, no doubt many people around Australia will gather to cook at the BBQ and swim in the surf. Families and friends will enjoy a relaxing time on a public holiday. Somewhere in the background, perhaps, there will hover a sense of satisfaction that we are “the lucky country” full of “mates and cobbers”, where there is “a fair go” for everyone, a country in which we can wave our flags, have our BBQs, kick back and relax.

Indeed, around the world, people who call Australia home will most likely be gathering, perhaps with fellow-Aussies, to celebrate the day. I know that when I was living in a foreign country, 40 years ago, I did just that—finding some other Australians in the university’s Graduate Student Housing to share in a meal as we celebrated “being Australian” in a foreign land.

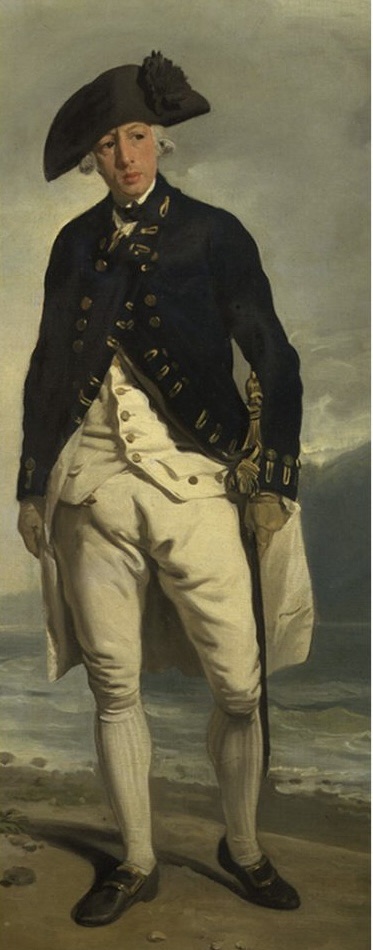

That was all almost half-a-lifetime ago, now; and my perspective on this has changed somewhat, I confess. I am still, as I was then, a fervent republican, believing that Australia needs to be a completely independent nation with no role at all for the imperialist blueblooded family whose forbears colonised this continent and who still have a formal, legal role in the affairs of this country, from many thousands of kilometres away.

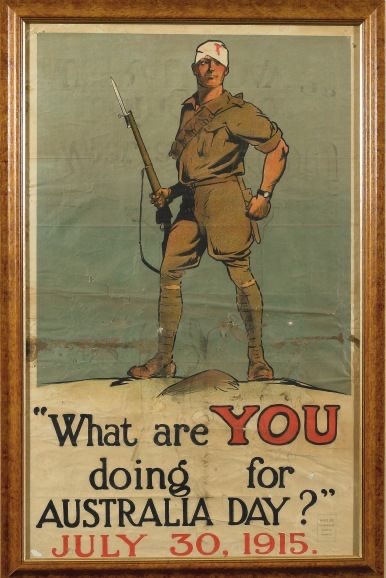

And I am still resolutely opposed to the primitive tribal tendencies inherent in nationalism, and its ugly cousin jingoism, because of the emotional damage that this does to impressionable minds, and the consequent savagery that it has unleashed in warfare across the years.

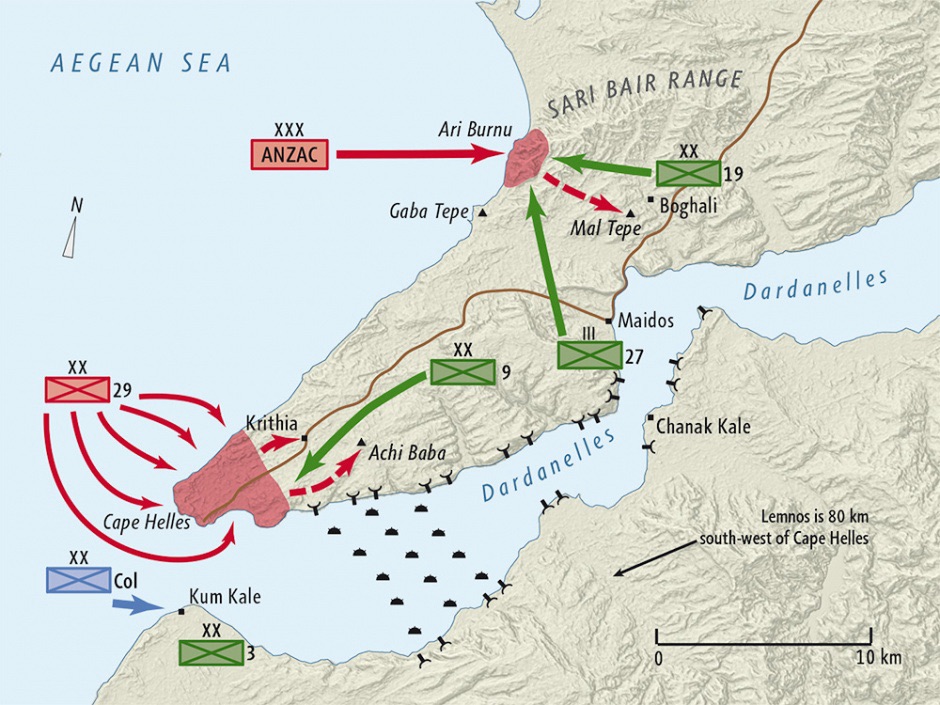

The cost of war is immense and long-enduring; the “victory” won by a nation in prosecuting war is fleeting by comparison. War means injury and death, to our own troops, and to the troops of those we are fighting against. Every death means a family and a local community that is grieving. There is great emotional cost just in one death, let alone the thousands and thousands that wars incur. To say nothing of the damage done to civilians, particularly women and children, as “collateral damage” in these nationalistic enterprises. Jingoistic nationalism fuels the appetite for warfare. So let us be wary about how far we are carried away by the rhetoric of living in “the lucky country” and extolling the virtues of this “great southern land”.

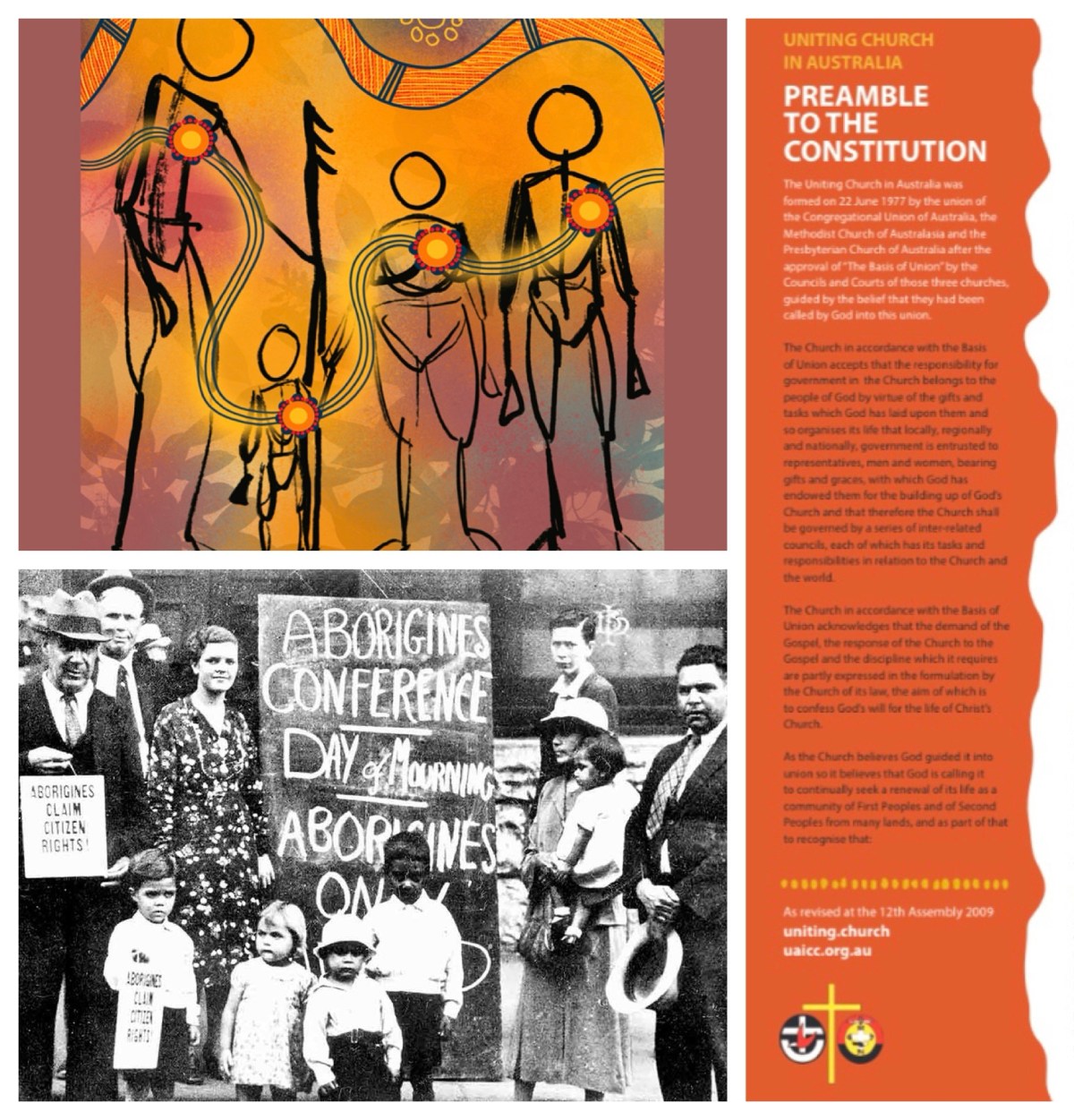

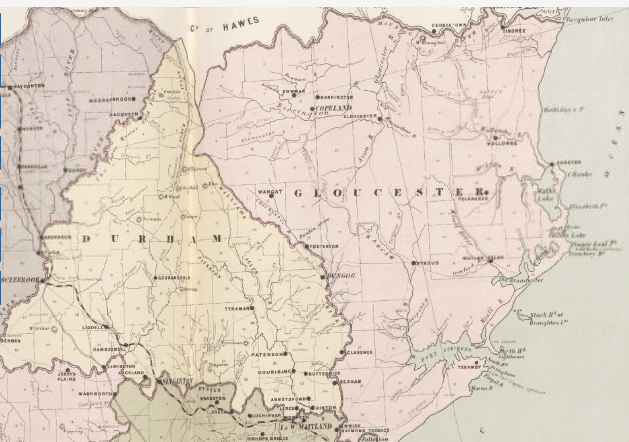

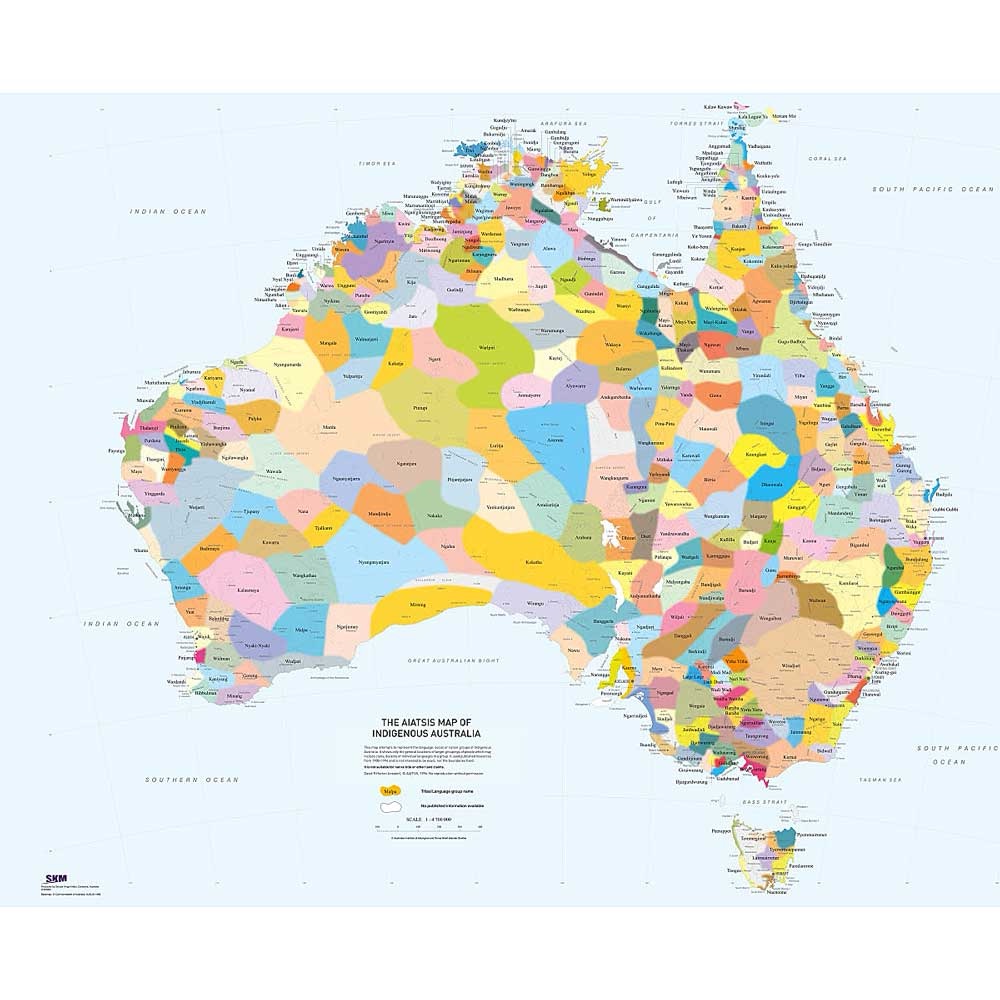

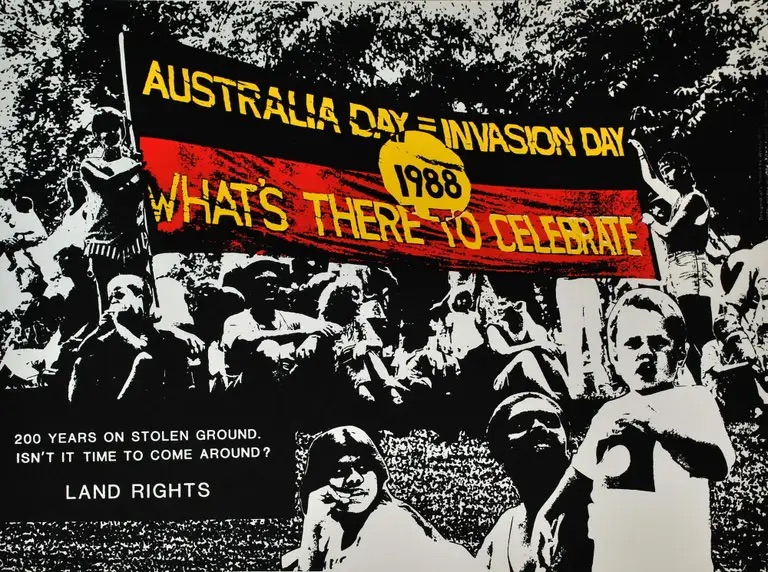

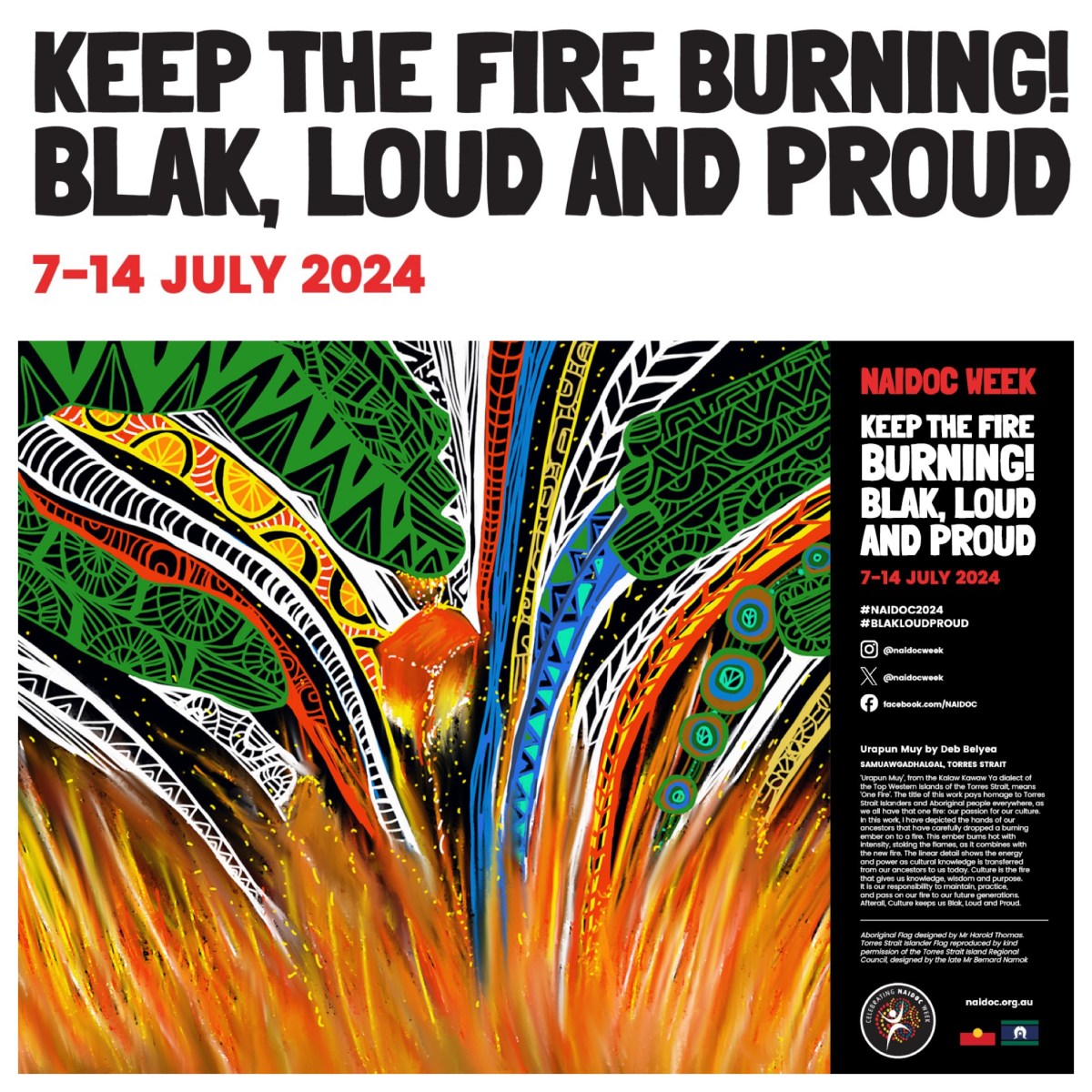

Standing in contrast to any nationalistic fervour that may well grip people on 26 January, I note that the many congregations of the Uniting Church have taken up the invitation of the Assembly to hold a Day of Mourning each year on the Sunday before 26 January. On that day, we are invited to reflect on the dispossession of Australia’s First Peoples and the ongoing injustices faced by First Nations people in this land. This resets and reorients the focus of the time around the “national day” of Australia. Indeed, it can provide a timely reminder that First People around this continent were forced into armed engagements with the invading colonisers, as they sought to press the frontiers of their newly-claimed colonial lands further and further.

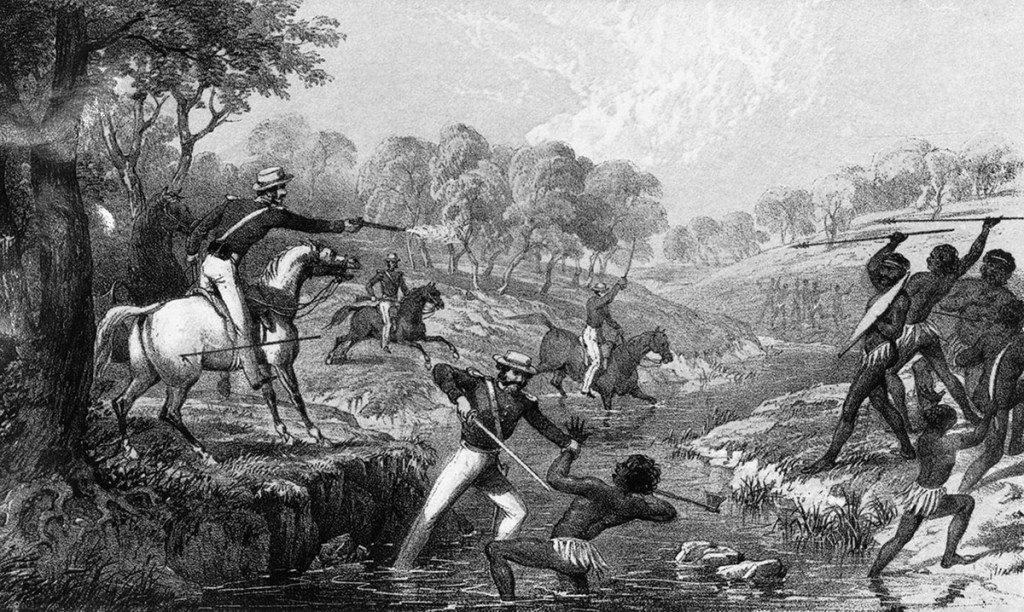

We are now aware that in these Frontier Wars, more Indigenous people died than in the formal military engagement of World War One; and, of course, many settlers also died in these conflicts. But First People were not armed with guns and did not have any way to push back against the superior firepower of the colonists. So they suffered greatly in these wars.

For those of us who are Second Peoples from many lands, the focus of a Day of Mourning offers an opportunity to lament that we were and remain complicit in the ongoing consequences of this dispossession and warfare. It also invites us to consider what we might do to move away from that negative trajectory.

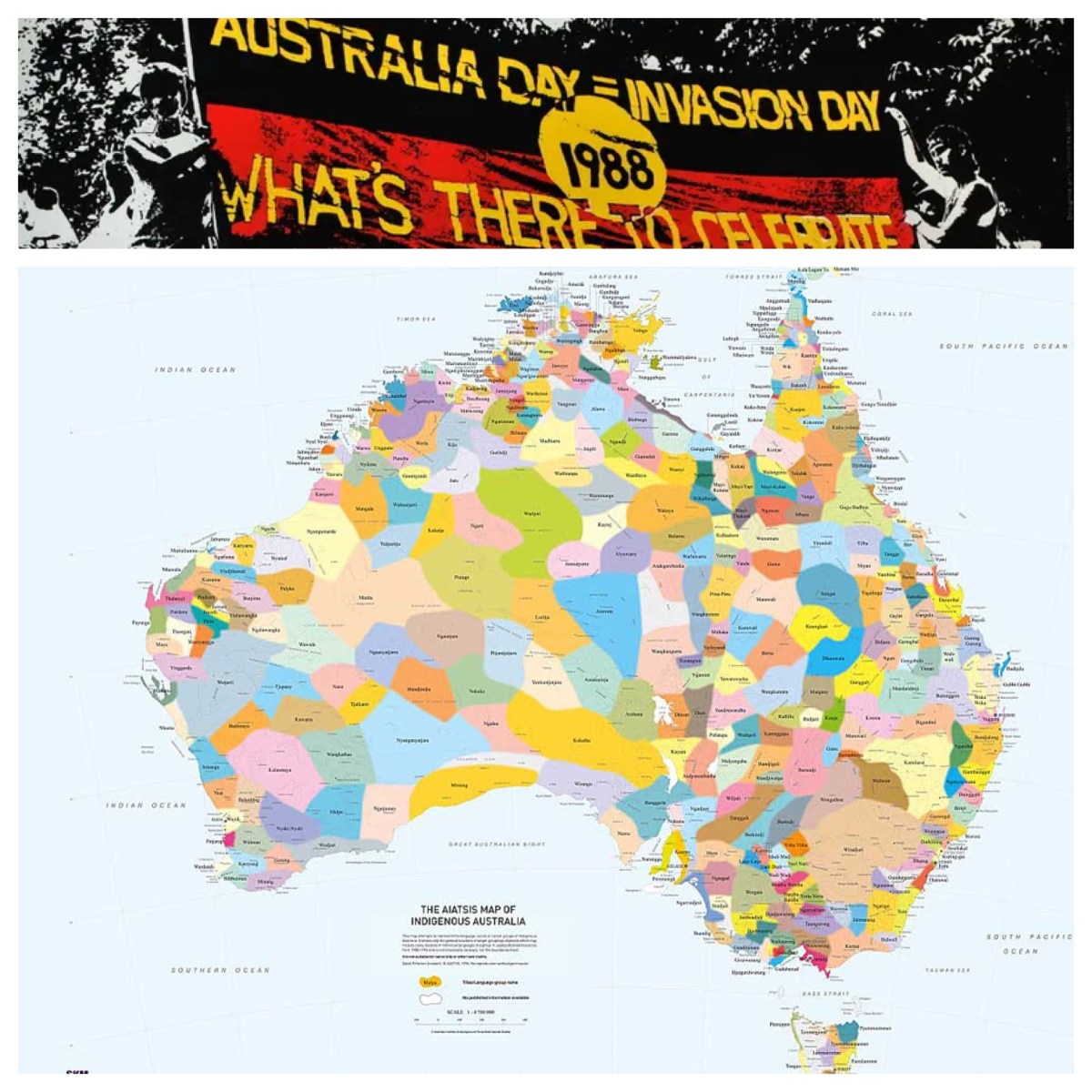

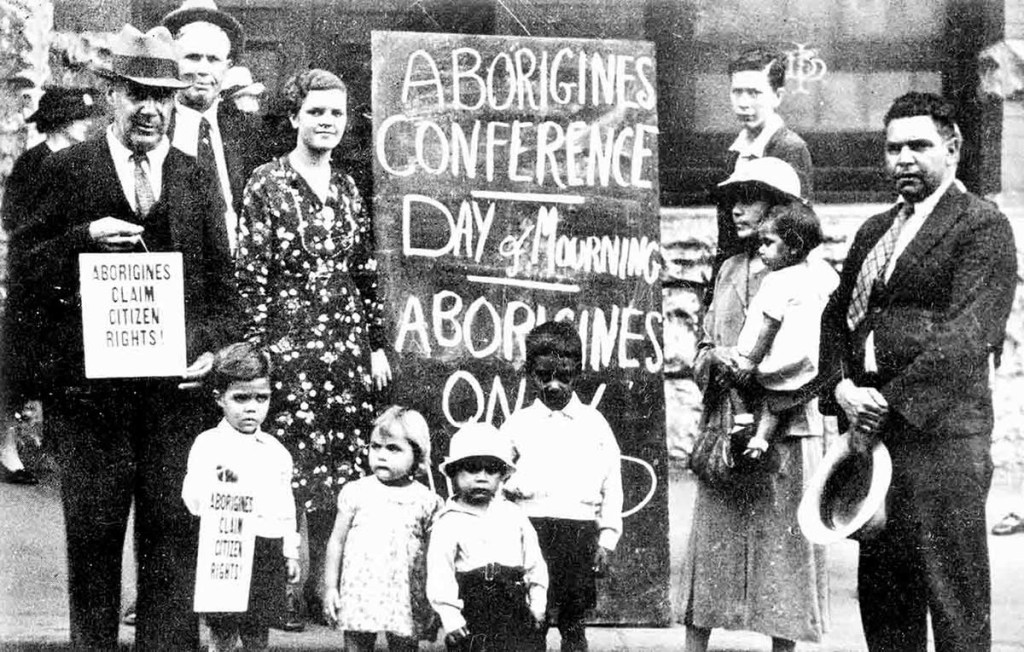

The observance of a Day of Mourning on the Sunday before 26 January looks back to the first Day of Mourning in 1938, after years of work by the Australian Aborigines League (AAL) and the Aborigines Progressive Association (APA). In a pamphlet published for the occasion, it was stated that “the 26th of January, 1938, is not a day of rejoicing for Australia’s Aborigines; it is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years’ so-called “progress” in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country.”

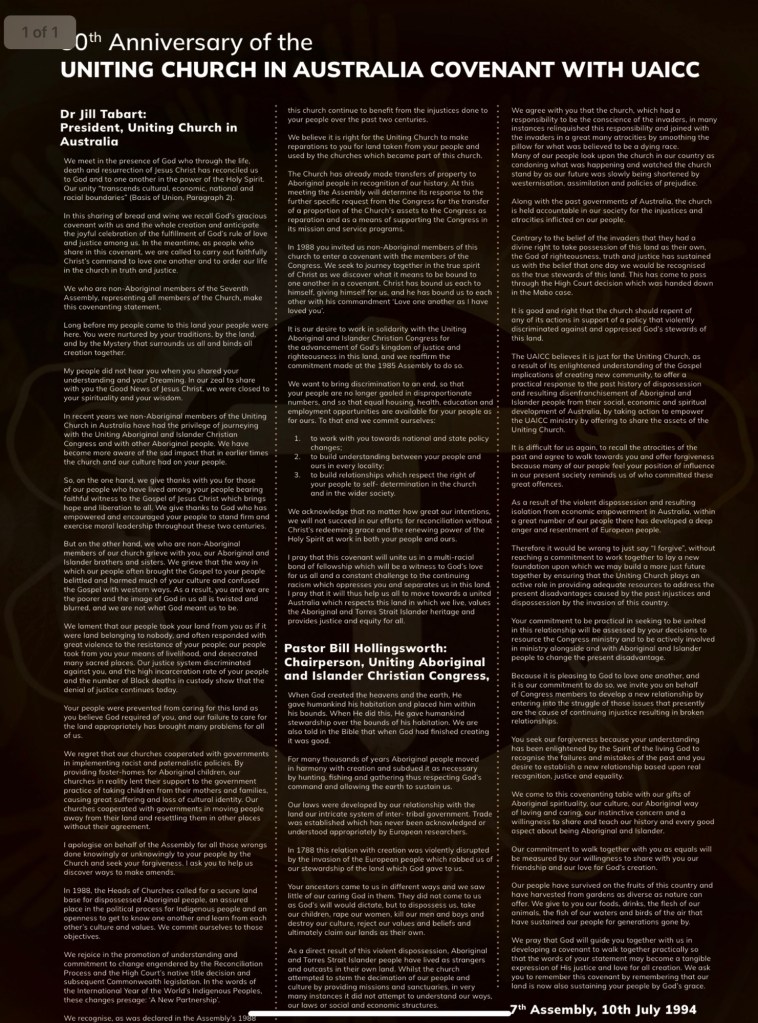

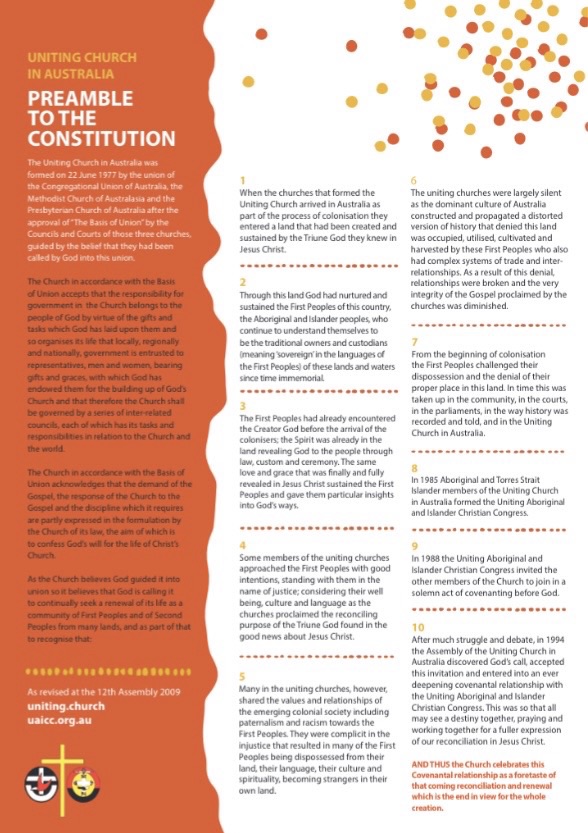

The national body of the Uniting Church, the Assembly, has acknowledged that our predecessors in the denominations which joined in 1977 to form the Uniting Church have been “complicit in the injustice that resulted in many of the First Peoples being dispossessed from their land, their language, their culture and spirituality, becoming strangers in their own land”. That itself is a cause for lament and mourning.

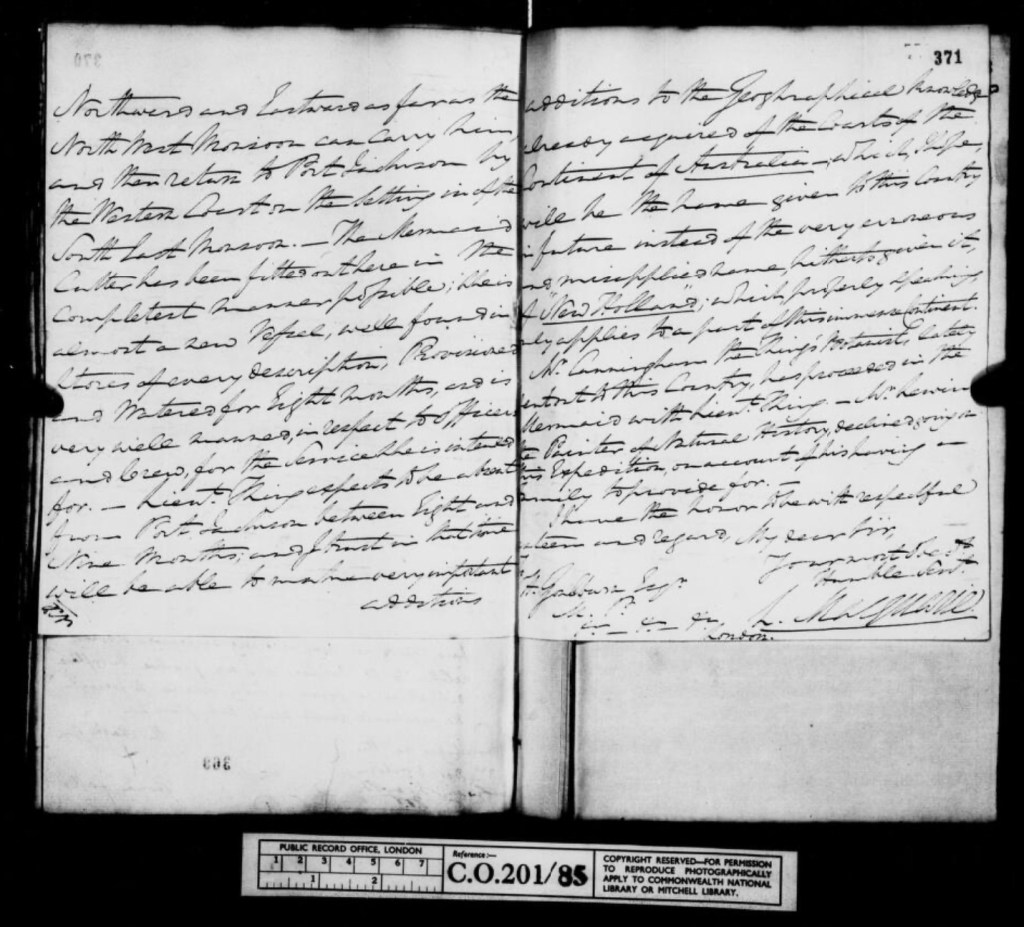

The Uniting Church Assembly has also recognised that people in these churches “were largely silent as the dominant culture of Australia constructed and propagated a distorted version of history that denied this land was occupied, utilised, cultivated and harvested by these First Peoples who also had complex systems of trade and inter-relationships”. [These quotations come from the Revised Preamble to the Constitution of the Uniting Church in Australia, adopted in 2009]

In worship resources prepared in relation to this Revised Preamble, we are invited to affirm the general belief that “the Spirit has been alive and active in every race and culture, getting hearts and minds ready for the good news: the good news of God’s love and grace that Jesus Christ revealed”, as well as the specific statement for our context, that “from the beginning the Spirit was alive and active, revealing God through the law, custom and ceremony of the First Peoples of this ancient land”. God is not confined to the way that we know things, the people we are familiar with, the customs and culture that we inhabit. God acts beyond all of these.

Thinking more about our First People, we are also invited by this Revised Preamble to confess “with sorrow the way in which their land was taken from them and their language, culture and spirituality despised and suppressed”, as well as the reality that “in our own time the injustice and abuse has continued; we have been indifferent when we should have been outraged, we have been apathetic when we should have been active, we have been silent when we should have spoken out.”

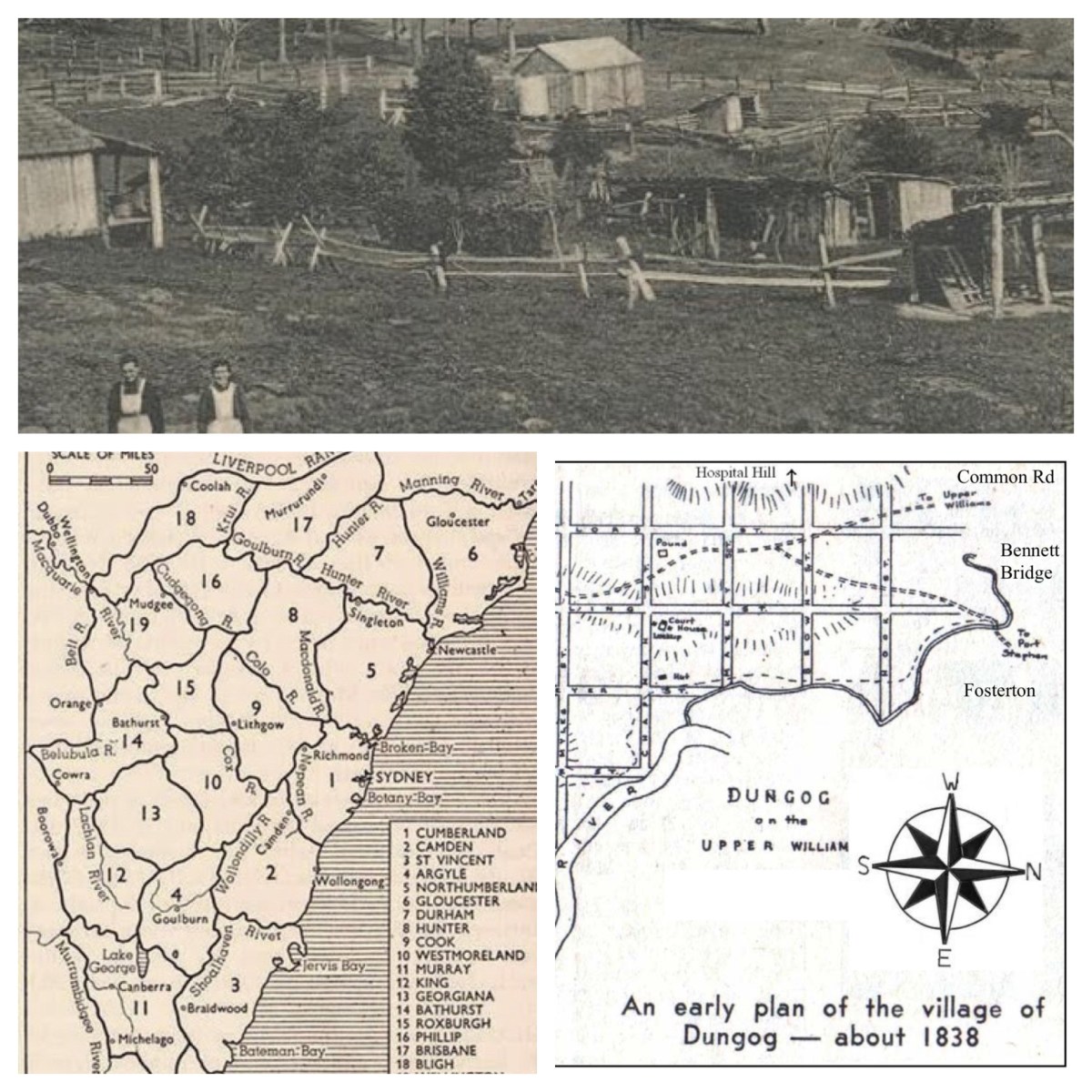

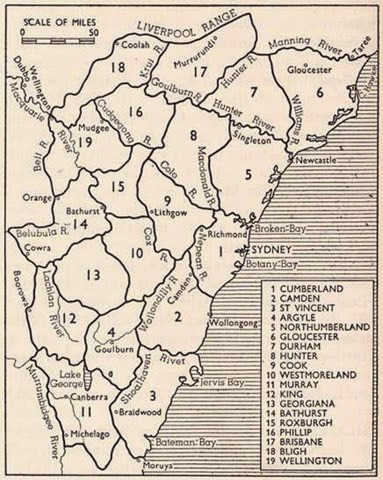

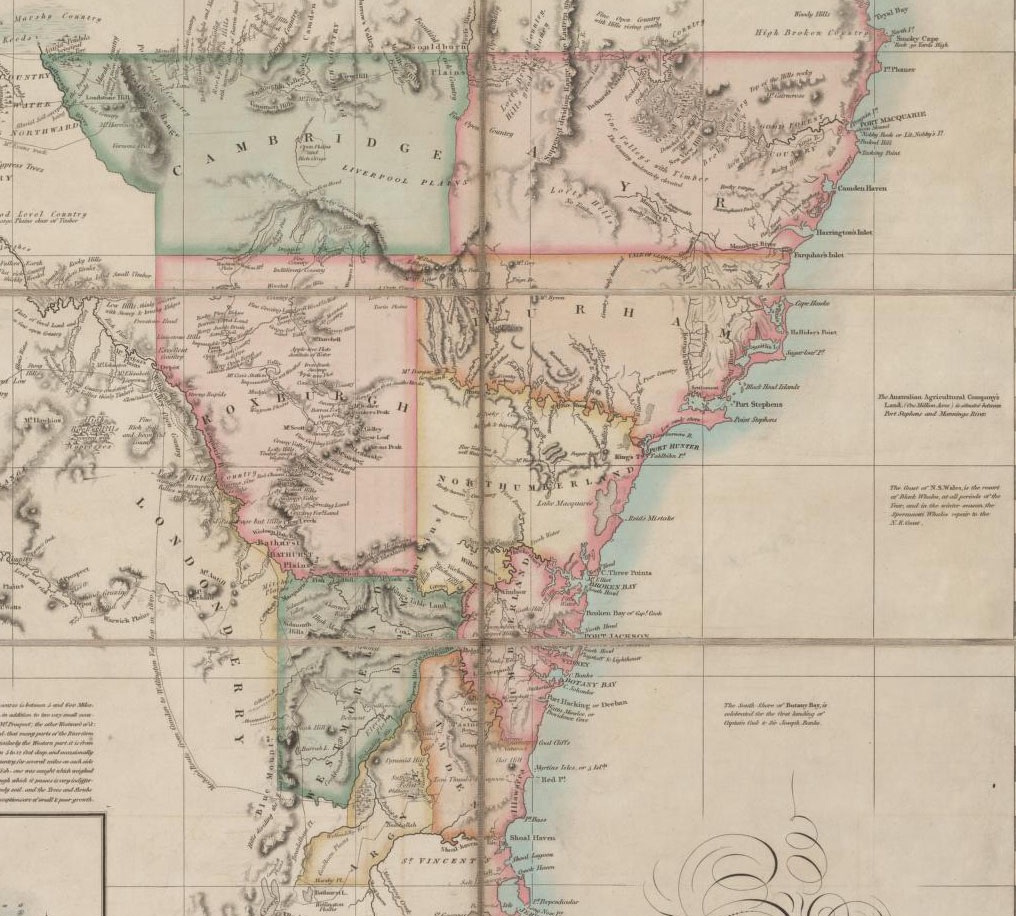

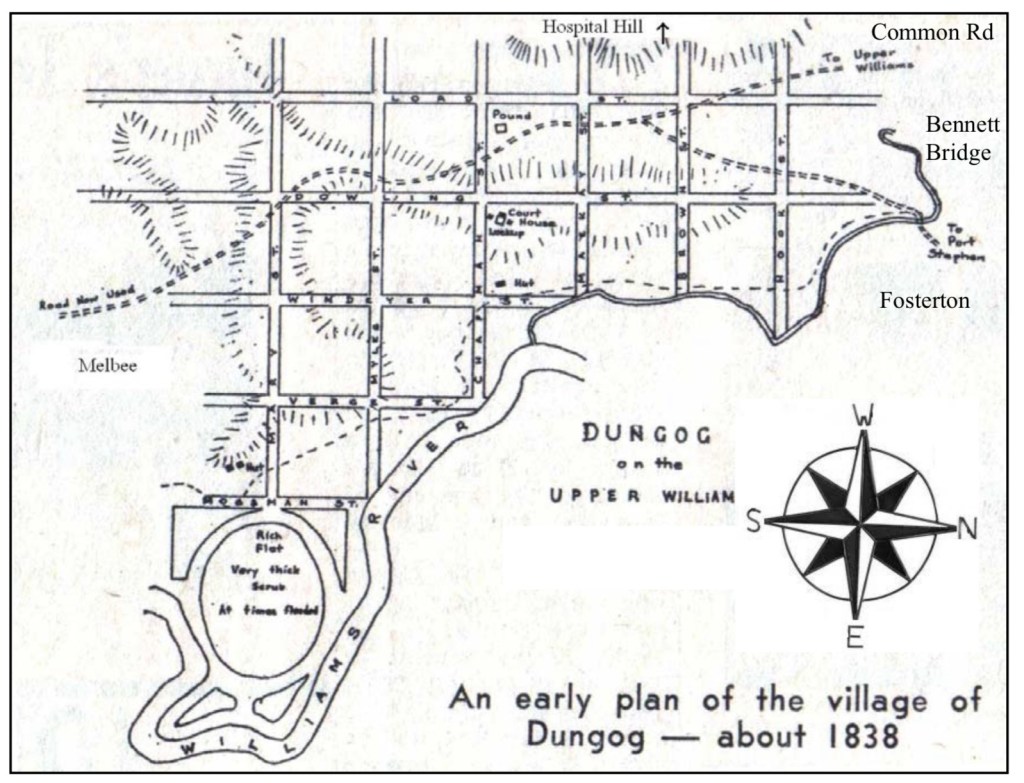

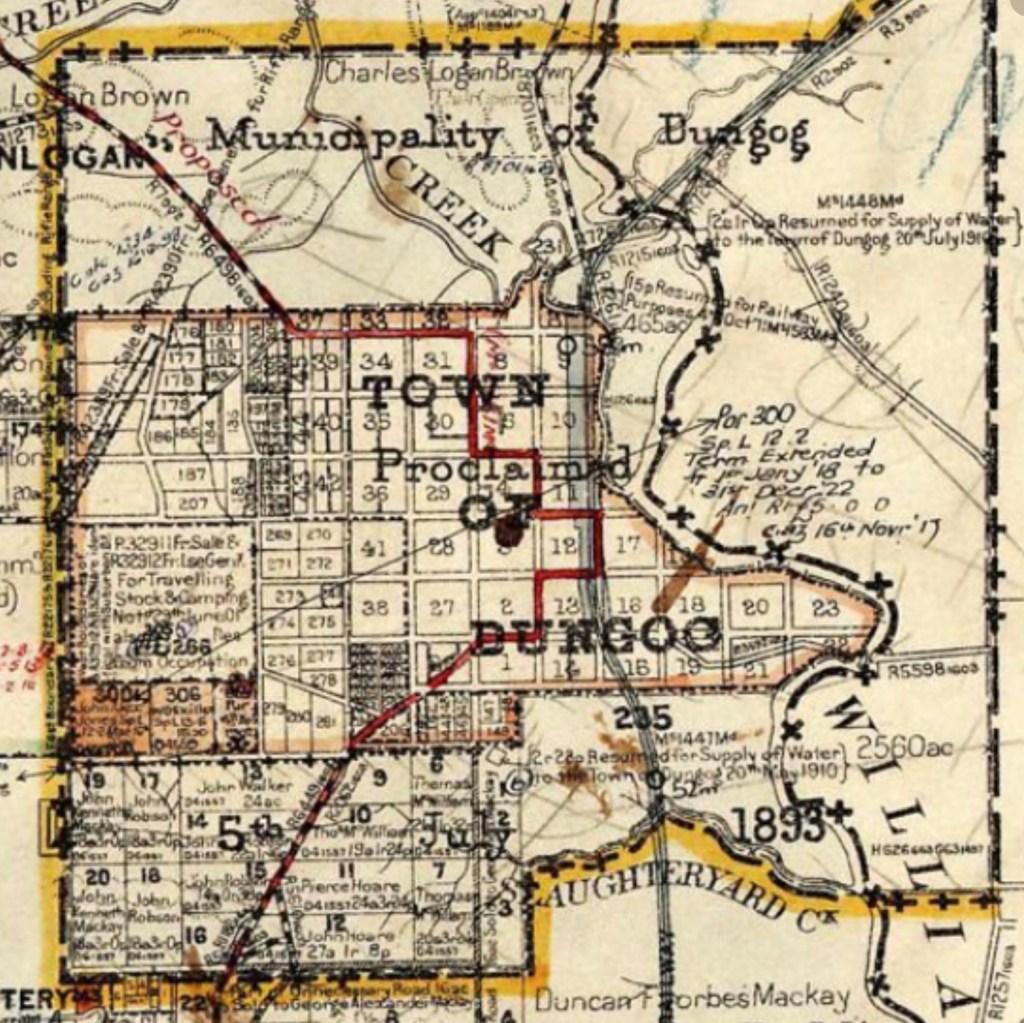

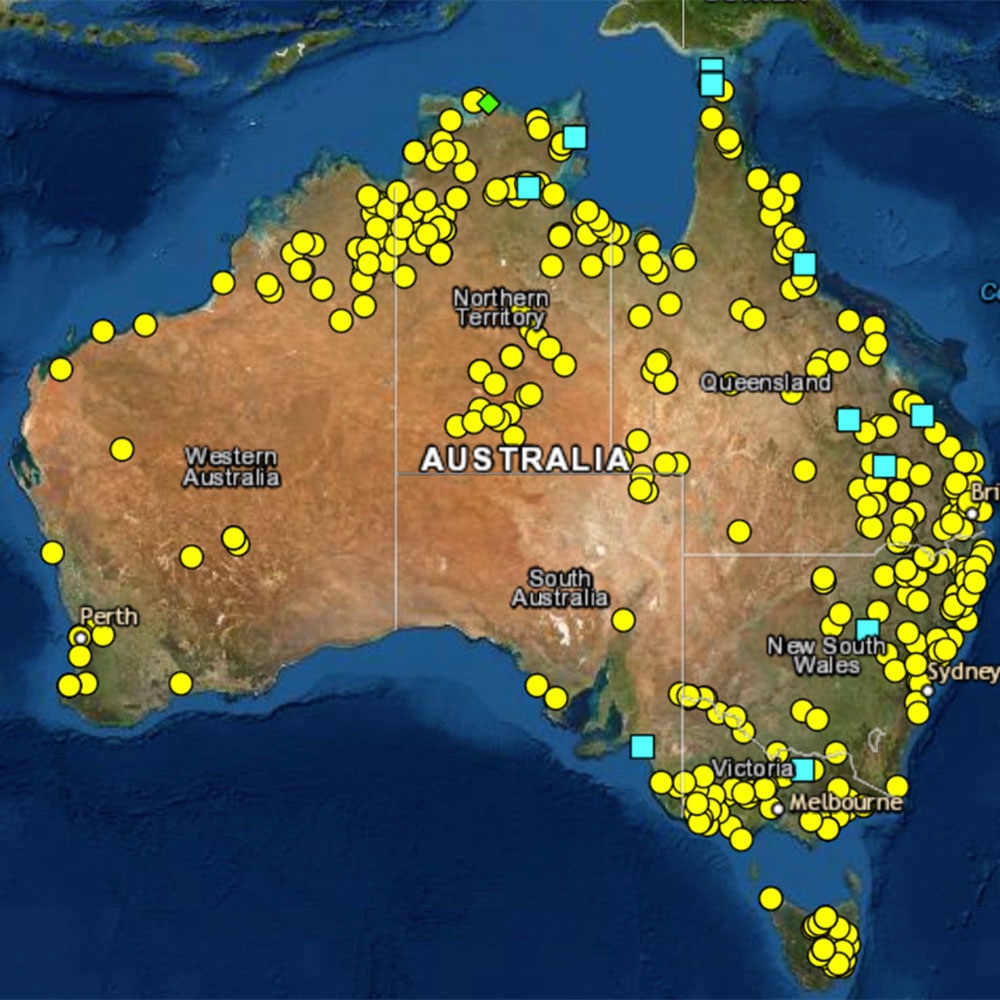

Injustice, discrimination, and oppression was not just the way of life for First People in times past; oppression, discrimination, and injustice still occur against First People today. Massacres do not happen in our time; but they were a feature of Australian life until 1932, probably in the lifetime of all of our parents. That is a national disgrace in our history. This map, compiled in the University of Newcastle, shows just how extensive these massacres were.

Children are not routinely taken from their families and placed into care homes; the policies about this brought mass removals to an end in the 1970s, but still today interventions are made amongst Indigenous people at a higher rate than other ethnic groups.

We had a Royal Commission into Aboriginal and Islander Deaths in Custody three decades ago, but still the rate of Indigenous deaths in custody remains many times higher than non-Indigenous people in custody. Some died by suicide as they were gripped by the black dog, that deep, deep despair, some by neglect as they were suffering significant medical conditions that were not treated, and some, as we have seen in graphic images and heard in voice recordings, have died through the violent interventions of police and custodial staff. It remains a national disgrace in our own time.

First People were ill-treated in the past; it is still the way that many of them are ill-treated today. Being the victim of racial discrimination, no matter how large or how seemingly small, is still a regular feature for many First People. We have not moved into a new and better era; we continue to perpetuate the sins of our past.

*****

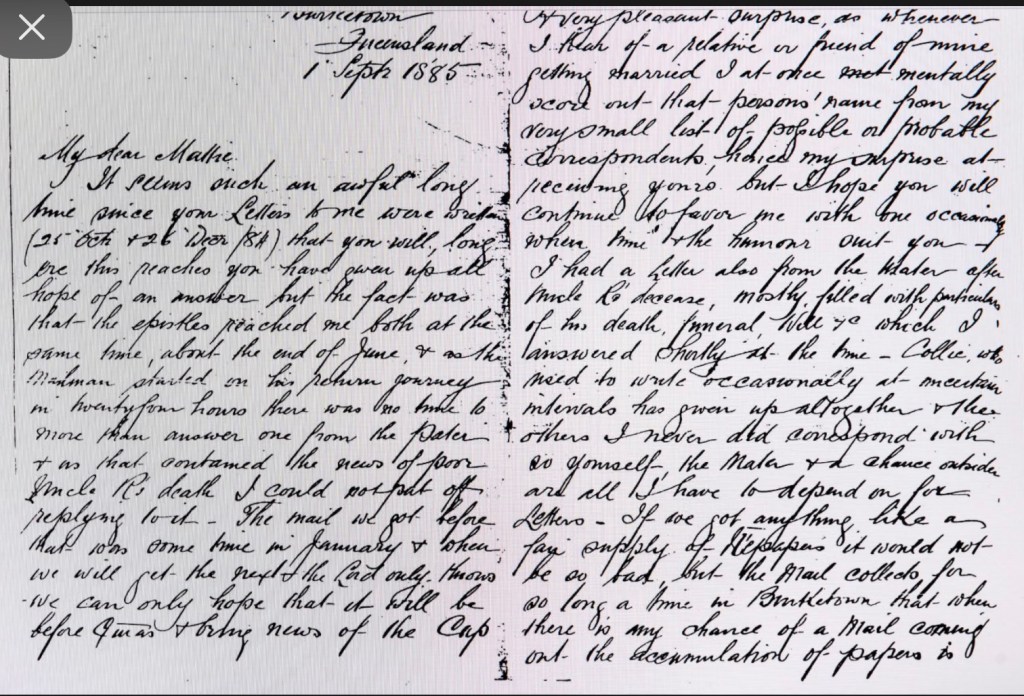

Elizabeth and I are friends with Aunty Karen, a Yeagl woman of the Budjalung nation further to the north of NSW, who lives on Gadigal land in Sydney. She recently wrote this post on Facebook:

“As we near ‘Australia Day’: Please remember the hurt and degradation this day means to Aboriginals Australia-wide. Intergenerational trauma exists (just ask the Jewish community; they still mourn the “Holocaust”). Enjoy yourselves, but remember this day has a different meaning for us Kooris. Please be respectful to each other. It’s time to acknowledge that we have survived, yes, but also carry the hurt and memories of what colonisation has done to our ancestors, and we have long memories.”

And in the latest issue of With Love to the World, I have reproduced a poem that Aunty Karen wrote some years ago, about the day which is our national day. If you’d like a copy of it, I have some WLW copies to give out. It is entitled “Walking Together”.

The droning of the Didgeridoo

as the music sticks plays along;

the sounds of my people’s Corroboree

as they sing their dreaming songs.

For 60,000 years or more,

my ancestors walked the land.

Our homes have changed in many ways,

sometimes hard to understand.

But though long gone are my tribal ways

after millennia of age,

I cannot forget our history:

for this is my heritage.

But to live in anger of the past is wrong,

as hate is such a wasted emotion.

So, let’s forgive the past, say “hello, my friend”,

and forge a greater nation.

In that spirit, let us approach 26 January, mindful of what has been done in the past, aware of the challenges and opportunities before us at the present, and committed to act with justice and to seek reconciliation in our nation.

See more on the UCA and First Peoples in these posts: