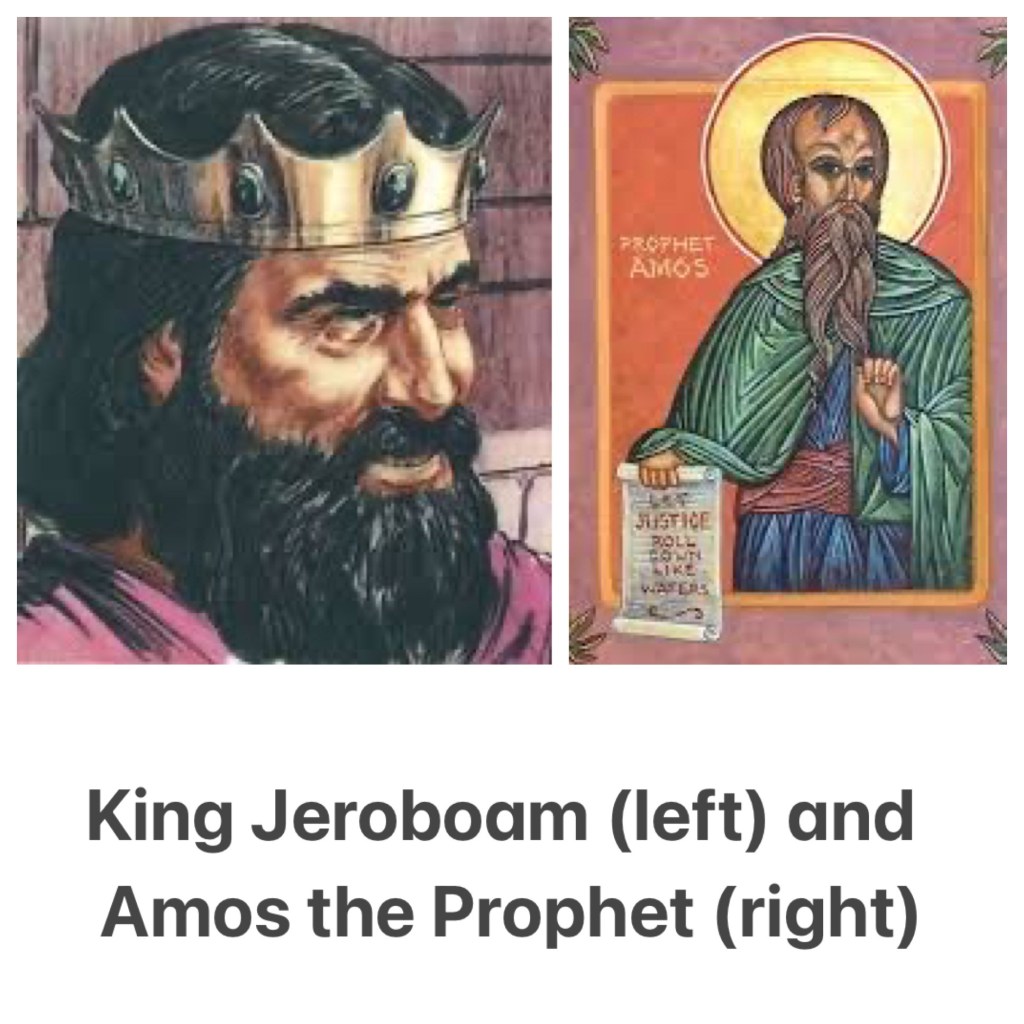

The prophet Amos lived in the northern kingdom of Israel during the reign of Jeroboam II, the thirteenth king of Israel, who reigned for four decades (786–746 BCE; see Amos 7:10). It was a time of prosperity, built on the trading of olive oil and wine with the neighbouring nations of Assyria to the north and Egypt to the south. Jeroboam, however, is remembered as a king who oversaw multiple acts of sinfulness during his years on the throne.

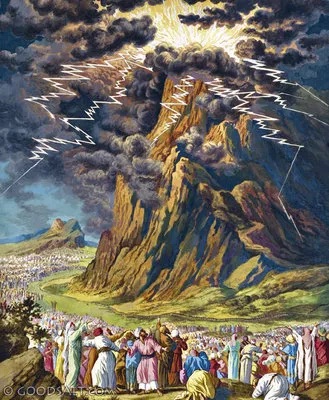

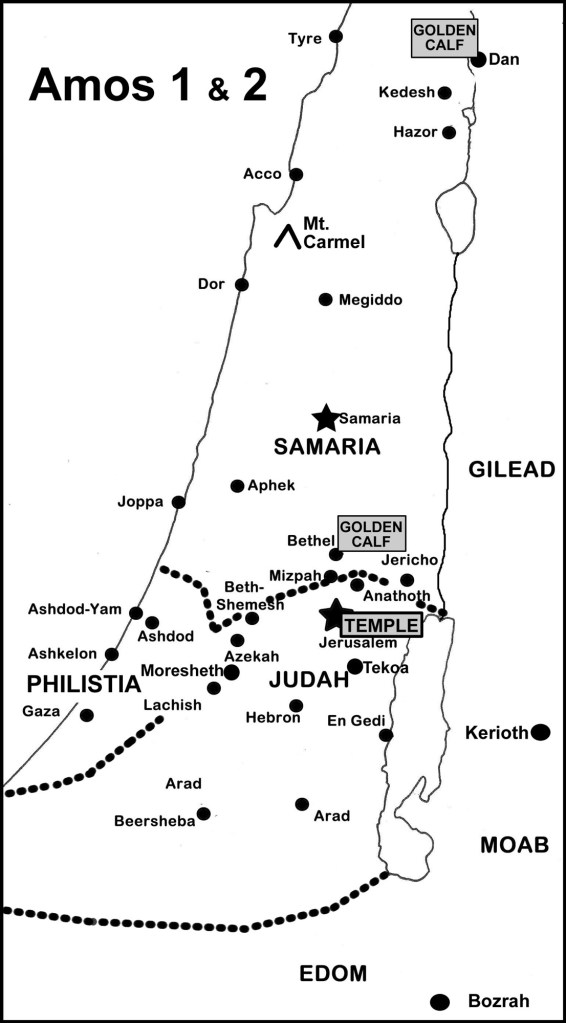

Most infamously, he replicated the sin of Aaron, who oversaw the creation of a golden calf during the time that the people of Israel were awaiting the return of Moses from his time on the top of Mount Sinai (Exod 32). Jeroboam had the city of Shechem built, as a direct challenge to the centrality of Jerusalem; and he had two golden claves built and installed, one at Bethel, the other at Dan (1 Ki 12:25–30).

For these and other persistent sins during his 22 years as king, reported at 1 Ki 12:31–33 and 13:33–34, Jerobaom incurred the divine wrath, such that God determined that “ the house of Jeroboam [was to be] cut it off and destroyed from the face of the earth” (1 Ki 13:34). Later passages in this book refer to “the sins of Jeroboam” (1 Ki 14:16; 15:30; 16:2, 19, 31; 2 Ki 10:29, 31; 13:2, 6, 11; 14:24; 15:9, 18, 24, 28; 17:22) and “the way of Jeroboam … and the sins that he caused Israel to commit, provoking the Lord, the God of Israel, to anger by their idols” (1 Ki 16:26).

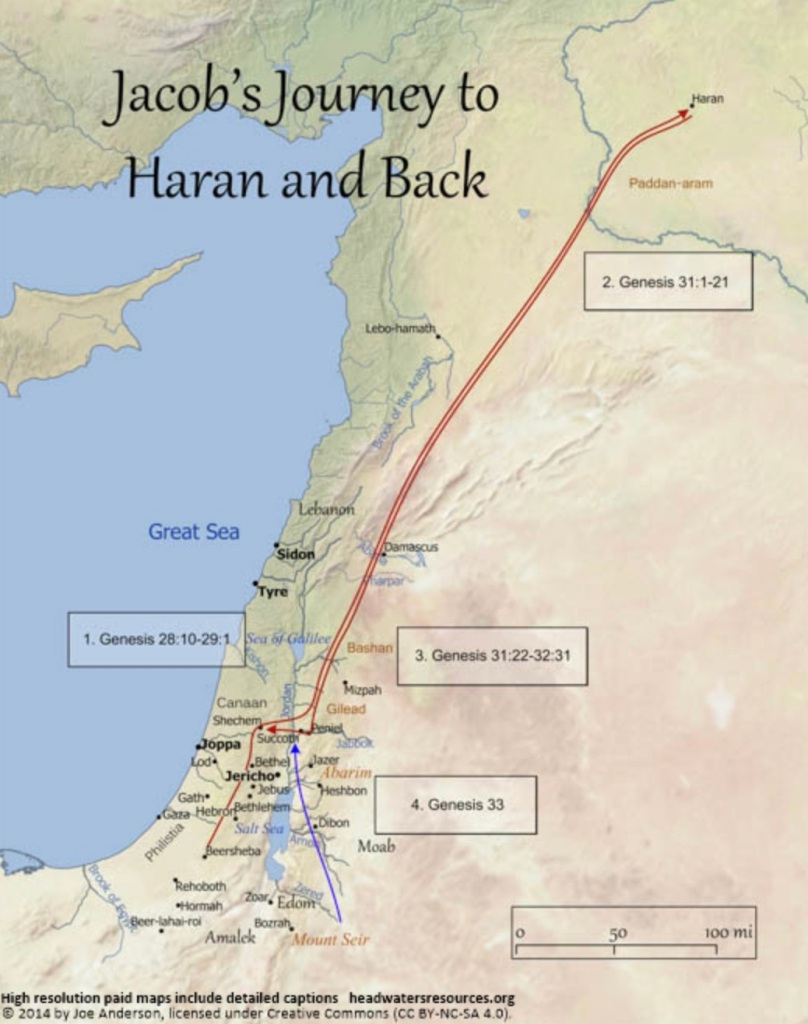

So although the Temple in Jerusalem was the focus for religious activity in the southern kingdom (Judah), Jeroboam had established a number of religious sites in the northern kingdom. Amos warns about the sites at Dan, Bethel, Gilgal and Beersheba (Amos 5:5; 8:14). At these places, not only was the Lord God worshipped, but idolatrous images were used in worship services (5:26). Amos is trenchant in his criticism of the worship that the people offer (5:21–27); embedded in this crisis is a doublet of poetry, words most often associated with Amos: “let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream” (5:24).

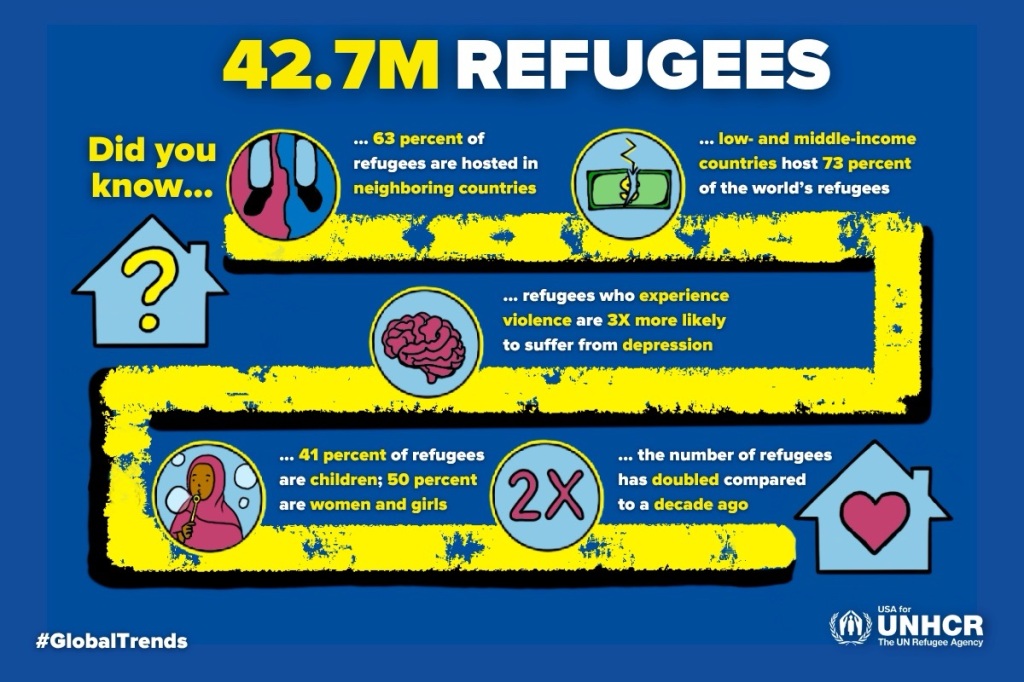

Indeed, it is the perpetration of social inequity within Israel that most causes him to convey the anger of divine displeasure. He admonishes the rich for the way that they mistreat the poor: “they sell the righteous for silver, and the needy for a pair of sandals—they who trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth and push the afflicted out of the way” (2:6–7); “you trample on the poor and take from them levies of grain” (5:11).

Again, Amos rails: “you trample on the needy and bring to ruin the poor of the land … buying the poor for silver and the needy for a pair of sandals, and selling the sweepings of the wheat” (8:4, 6). In a biting oracle, he criticises the “cows of Bashan who are on Mount Samaria” for the way they “oppress the poor, crush the needy” (4:1).

Bashan was the mountainous area to the northeast of Israel (Ps 68:15), which rejoiced in majestic oaks (Isa 2:13) and extensive pasture lands (1 Chron 5:16). The luxurious lifestyle of these people can well be imagined. The reference to “winter houses … summer houses … houses of ivory … and great houses” (3:15) is telling. Luxury and opulence is evident amongst the wealthy.

So, too, is the description of “those who lie on beds of ivory, and lounge on their couches, and eat lambs from the flock, and calves from the stall; who sing idle songs to the sound of the harp, and like David improvise on instruments of music; who drink wine from bowls, and anoint themselves with the finest oils” (6:4–6). The extravagance of the wealthy is obvious, juxtaposed against the plight of the poor, as we have noted.

Amos indicates that God had given Israel a number of opportunities to repent, “yet you did not return to me” (4:6, 8, 9, 10, 11). God pleads for Israel to “seek me and live” (5:4), “seek the Lord and live” (5:6), “seek good and not evil, that you may live” (5:14).

But this is all in vain; ultimately, the prophet insists, the Lord God will bring on the day of the Lord—a day of “darkness, not light, and gloom with no brightness in it” (5:18–20). God is determined; “the great house shall be shattered to bits, and the little house to pieces” (6:11); later, he insists again, “the dead bodies shall be many, cast out in every place” (8:3).

In so many reports of prophetic activity, it is justice which is the heart of their message—God’s justice; the justice which God desires for the people of God; the justice which God speaks through the voice of the prophets; the justice that God calls for in Israel; the justice that provides the measure against which Israel will be judged, and saved, or condemned.

Moses himself was charged with ensuring that justice was in place in Israelite society. One story told of the time after the Israelites had escaped from Egypt places Moses as a judge. Whilst in the wilderness of Sin, being visited by his father-in-law Jethro, we learn that “Moses sat as judge for the people, while the people stood around him from morning until evening” (Exod 18:13).

Noticing that Moses was overwhelmed by the volume of matters requiring adjudgment, Jethro suggested—and Moses adopted—a system whereby appointed men who “judged the people at all times; hard cases they brought to Moses, but any minor case they decided themselves” (Exod 18:14–16). The charge given to these men is clear: they are to give a fair hearing to every member of the community, and they “must not be partial in judging: hear out the small and the great alike; [do] not be intimidated by anyone, for the judgment is God’s” (Deut 1:16–17).

Prophets coming after Moses thus inherited this responsibility to ensure that justice was upheld within society. The most famous prophetic word of Amos is, as we have noted, his call for “justice and righteousness” (Amos 5:22). Micah asks the question, “what does the Lord require of you but to do justice?” (Mic 6:8), while through the prophet Hosea, the Lord God promises to Israel, “I will take you for my wife in righteousness and in justice, in steadfast love, and in mercy” (Hos 2:19).

Isaiah ends his famous love-song of of the vineyard by declaring that God “expected justice” (Isa 5:7) and he tells the rebellious people of his day, “the Lord is a God of justice; blessed are all those who wait for him” (Isa 30:18). He proclaims God’s judgement on those who “turn aside the needy from justice … and rob the poor of my people, that widows may be your spoil, and that you may make the orphans your prey!” (Isa 10:1–2).

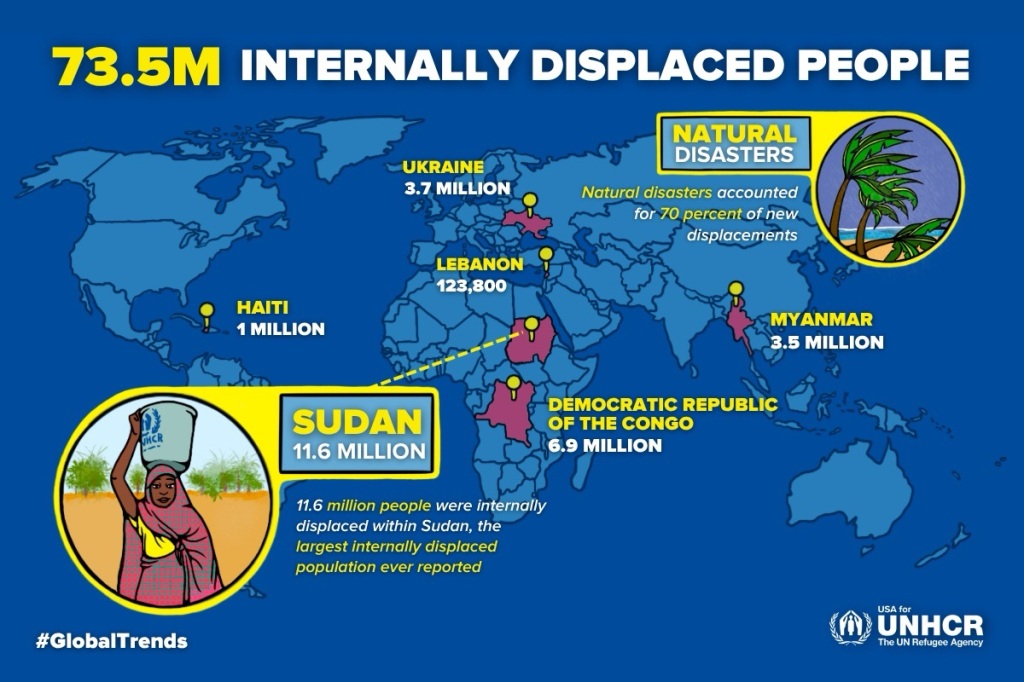

Other prophets join their voices to Isaiah’s declaration. Ezekiel laments that “the sojourner suffers extortion in your midst; the fatherless and the widow are wronged in you” (Ezek 22:7). Jeremiah encourages the people of Jerusalem with a promise that God will allow them to continue to dwell in their land if they “do not oppress the sojourner, the fatherless, or the widow” (Jer 7:5–7).

Second Isaiah foresees that the coming Servant “will bring forth justice to the nations” (Isa 42:1) and knows that God’s justice will be “a light to the peoples” (Isa 51:4). The words of Third Isaiah continue in this prophetic stream, for this anonymous prophet begins his words with a direct declaration, “maintain justice, and do what is right” (Isa 56:1). He goes on to articulate his mission as being “to bring good news to the oppressed, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and release to the prisoners” (Isa 61:1), thereby demonstrating that “I the Lord love justice” (Isa 62:8).

This commitment of Amos and many of the prophets resonates also with the psalmist, who praises “the God of Jacob … who executes justice for the oppressed; who gives food to the hungry … [who] sets the prisoners free, [who] opens the eyes of the blind, [who] lifts up those who are bowed down [and] loves the righteous, [who] watches over the strangers [and] upholds the orphan and the widow” (Ps 146:5, 7–9). See

https://johntsquires.com/2023/05/14/father-of-orphans-and-protector-of-widows-psalm-68-easter-7a/