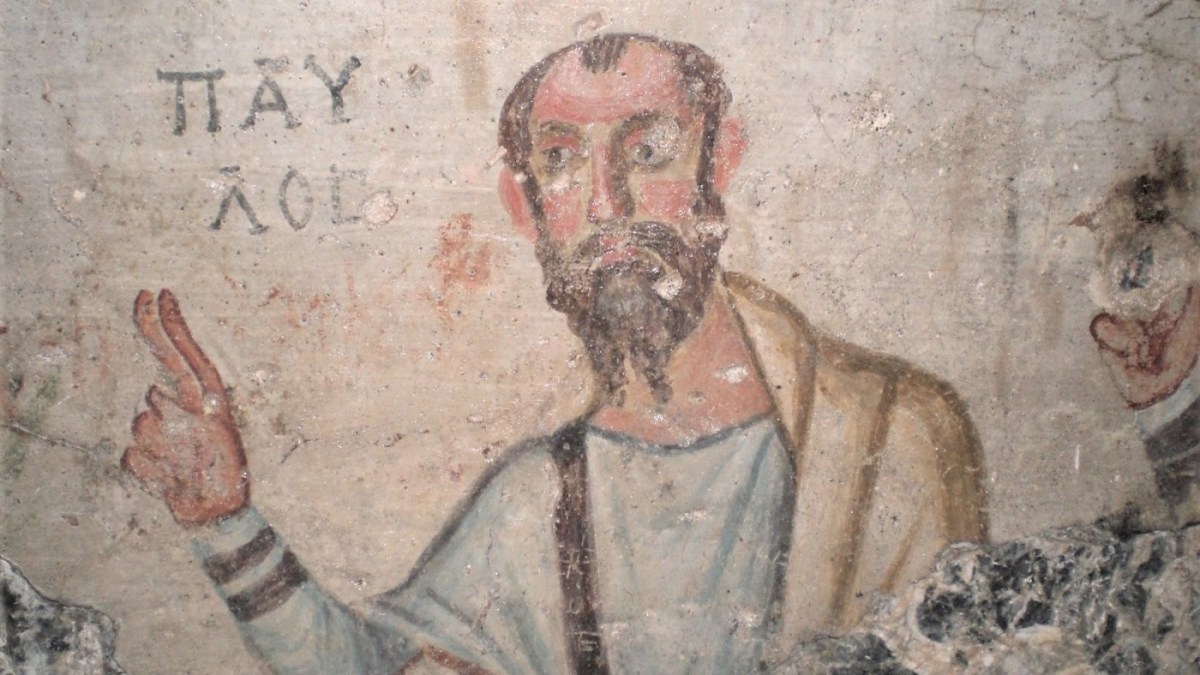

The cross is the benchmark for understanding how believers are to behave, how they are to relate to one another, and how the community that they form is to be described. This is the thesis that Paul and Sosthenes propose near the start of their lengthy letter to “the church of God that is in Corinth, to those who are sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints” (1 Cor 1:1–2), and also to “all those who in every place call on the name of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1:2). And as we have already noted, “the word of the cross” features prominently in the authentic letters of Paul.

The thesis is stated in a rhetorically balanced, theologically incisive two-part statement, the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God (1:18). The claim is worked out in the first two chapters of the letter, in passages that we will hear this week (1 Cor 1:18–31) and then next week (2:1–12). It then serves as the basis for much of the ethical and theological discussion that follows in later chapters of the letter.

In the two passages currently in view, Sosthenes and Paul remind the Corinthians that “we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles” (1:23), that they “decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ, and him crucified” (2:2), and that the paradoxical wisdom that is at the heart of the story of Jesus, “none of the rulers of this age understood this; for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory” (2:8).

The rhetorical structuring of this paradoxical argument is evident throughout the whole of the passage that the lectionary offers for this Sunday (1:18–31). There is a neat symmetry of clauses in each verse of the passage, with frequent use of balancing subsidiary phrases continuing the symmetrical structure. I’ve attempted to show this schematically as follows:

*****

To begin, Sosthenes and Paul ground their argument in prophetic declarations drawn from the Hebrew scriptures—in fact, explicit citations bookmark their argument at 1:19 (quoting Isaiah) and 1:31 (quoting Jeremiah). This is typical of rabbinic literature, where an initial citation (a subsidiary text) begins an argument, and then the primary text for the matter being addressed concludes the argument. This was the fourth of Rabbi Hillel’s seven principles for scripture interpretation (Aboth de Rabbi Nathan 37).

So there should be no surprise that we find such a technique employed in a letter written by Sosthenes, a leader of the synagogue (the place where scripture interpretation was taught and debates about scripture flourished), and Paul, trained as a Pharisee (at the feet of Gamaliel, if Acts 22:3 reflects historical reality) and well-versed in the Torah, the first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures (Phil 3:5; Rom 7:12, 22). As Jews immersed in the knowledge of Torah and the application of scripture to daily life, this way of speaking and writing was second nature to them.

After stating their thesis (1:18), Sosthenes and Paul cited the prophet Isaiah in support (Isa 29:14). In the typical rabbinic fashion of arguing a point, this first quotation is the subsidiary text for their argument. The words come from an oracle that the prophet delivers when Israel and Judah had been invaded by the Assyrian power to the north (2 Kings 17–19). This invasion of 721 BCE is characterised by Isaiah as an expression of God’s judgement (Isa 28:21–22). The northern kingdom had been conquered (2 Kings 17) and the southern kingdom was invaded (2 Kings 18). Two decades later, under Sennacherib, the city of Jerusalem itself was under siege (Isa 29:1–3). Ultimately Sennacherib withdrew his army back to Nineveh and was killed by his sons (2 Kings 19:36–37).

Whilst the experience of the people in the besieged city of Jerusalem was one of “moaning and lamentation” (Isa 29:2), the prophet presses the claim that this is brought about by God himself: “the Lord has poured out upon you a spirit of deep sleep; he has closed your eyes, you prophets, and covered your heads, you seers” (Isa 29:10). This, the prophet insists, “comes from the Lord of hosts; he is wonderful in counsel, and excellent in wisdom” (Isa 28:29).

Because the people claim allegiance to God but fail to live according to the covenant they have made with God—“their worship of me is a human commandment learned by rote” (Isa 29:13)–God’s intervention through the Assyrian encirclement of Jerusalem will mean that “the wisdom of their wise shall perish, and the discernment of the discerning shall be hidden” (Isa 29:14). Eventually, through this intense hardship, “those who err in spirit will come to understanding, and those who grumble will accept instruction” (Isa 29:24).

It is this message of the paradoxical inversion of the widely-accepted wisdom by divine intervention that the apostle and his co-author draw on, when they remind the Corinthians of God’s way: “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart” (1 Cor 1:19, quoting Isa 29:14b).

*****

In developing their argument in the following verses, Sosthenes and Paul explain this inversion to the Corinthians in three compact sequences. First, they pose a series of three rhetorical questions ending with a fourth question that expounds the paradoxical nature of how God acts:

The implied answer, of course, is “yes”.

Then follows a doublet with matching halves (wisdom of God, wisdom of the world; foolishness, salvation):

The pattern of wisdom-wisdom, folly-?? is broken with the declaration of salvation for believers; this is what “God decided”.

The third sequence contrasts Jews with Greeks (that is, Gentiles) but then places both of them in contrast to the proclamation of “Christ crucified”. The word of the cross functions as the definitive marker; this is the pivot on which the section turns.

The word of the cross—the proclamation of “Christ crucified”—might be understood as a stumbling block and a folly, but is actually a demonstration of divine power and wisdom. It is in the cross that the age-old dynamic of how God works is seen: it is an upheaval, a reversal, an overturning of received wisdom—just as Isaiah had been proclaiming to his fellow Judahites eight centuries earlier.

The conclusion is made clear in a punchy doublet in parallel paradox:

*****

In what follows next, attention turns to the actual community of believers in Corinth. The letter writers invite the believers in Corinth to “consider your own call, brothers and sisters”, followed by two triplets of rhetorically powerful statements:

That few were wise, powerful, or born as nobles in Corinth should come as no surprise. Certainly, a number of high-status names are mentioned in the letter (Stephanus, Fortunatus, and Acaicus at 16:17; and perhaps Chloe, if “Chloe’s people” at 1:11 are her servants), and other letters demonstrate a similar presence of high-status people, such as those who host “the church in the house of” Aquila and Priscilla (1 Cor 16:19; Rom 16:3), as well as a number of those mentioned in the string of names in Rom 16:3–16.

However, later in the letter we learn that when the community of believers comes together, some enjoy a rich meal and get drunk, while others starve (1 Cor 11:21). The condemnation is on those who “humiliate those who have nothing” (11:22); they are instructed, “when you come together to eat, wait for one another” (11:33). Here, as in a number of other places in the letter, the teaching is given that all members of the community are to be regarded as equal, for “in the one Spirit we were all baptized into one body—Jews or Greeks, slaves or free—and we were all made to drink of one Spirit” (12:13).

Indeed, in the second century, Pliny would describe Christians as being “of every age, of every rank, of both sexes” and “not only in the towns, but also in the villages and farms” (Pliny, Epist. 10.96.9). And social-scientific commentators on the early Jesus movement have published careful analyses that support the notion that early Christian communities contained a cross-section of society (see Gerd Thiessen, The First Followers of Jesus, on the rural origins of the movement, and Wayne Meeks, The First Urban Christians, on its consolidation in the cities of the Roman Empire).

So in the rhetorically powerful argument of 1:18–31, God’s paradoxical choice is emphasised; God chose fools, weaklings, and lowly despised people, not wise, powerful, noble-born. In the second triplet, the final affirmation is extended with another rhetorical intensifier, reinforcing “the wisdom from God” with three additional theological claims (righteousness, sanctification, and redemption).

*****

At the end of the argument, in typical rabbinic style, a closing citation clinches the case, with words from the prophet Jeremiah (Jer 9:23–24): “as it is written, ‘Let the one who boasts, boast in the Lord’” (1 Cor 1:31). This is the primary scripture passage which undergirds the argument that commenced in 1 Cor 1:19 with the citation of the subsidiary passage from Isaiah.

Jeremiah lived at a turning point in the history of Israel. The northern kingdom had been conquered by the Assyrians in 721 BCE; the elite classes were taken into exile, the land was repopulated with people from other nations (2 Kings 17). The southern kingdom had been invaded by the Assyrians in 701 BCE, but they were repelled (2 Kings 18:13–19:37). King Hezekiah made a pact with the Babylonians, but the prophet Isaiah warned that the nation would eventually fall to the Babylonians (2 Kings 20:12–19). Babylon conquered Assyria in 607 BCE and pressed hard to the south; the southern kingdom fell in 587 BCE (2 Kings 24–25) and “Judah went into exile out of its land” (2 Kings 25:21).

Jeremiah lived in the latter years of the southern kingdom, through into the time of exile. He was sent into exile in Egypt (Jer 43:1–8), even though most of his fellow Judahites were taken to Babylon. The difficult experiences of Jeremiah as a prophet colour many of his pronouncements. That is certainly the case for the long oracle from which the one-line quotation at 1 Cor 1:31 is drawn.

“My joy is gone, grief is upon me, my heart is sick”, the prophet laments (Jer 8:18), posing a question that has come into popular speech in later times: “Is there no balm in Gilead? Is there no physician there? Why then has the health of my poor people not been restored?” (Jer 8:22).

Jeremiah warns of the coming devastation that the Babylonians will bring, framing it as God’s righteous judgement: “I will make Jerusalem a heap of ruins, a lair of jackals; and I will make the towns of Judah a desolation, without inhabitant” (Jer 9:11). Accordingly, the prophet poses the question, “who is wise enough to understand this?” (Jer 9:12), calls for the people to mourn (Jer 9:17–23), and advises them that the Lord declares, “Do not let the wise boast in their wisdom, do not let the mighty boast in their might, do not let the wealthy boast in their wealth; but let those who boast boast in this, that they understand and know me, that I am the Lord; I act with steadfast love, justice, and righteousness in the earth, for in these things I delight, says the Lord” (Jer 9:23–24).

This is the declaration from which Sosthenes and Paul take the one line to draw the argument to a close, pressing the paradoxical way by which God overturns the power of the world and inverts the wisdom of the world. There can be no boasting in human wisdom. Trust can only be placed in the wisdom of God, which has its own logic and distinctive purpose. Boasting is feasible only in this context: “as it is written, ‘Let the one who boasts, boast in the Lord’” (1 Cor 1:31). That is what “the word of the cross” is, to the believers in Corinth–and to “all those who in every place call on the name of our Lord Jesus Christ”.

*****