The story that is told in the Gospel for this coming Sunday (included in the longer reading of Mark 8:27—9:8) is a story about being changed; about being transformed. It’s a story that shows that being transformed means you are able to stand and challenge others to be transformed.

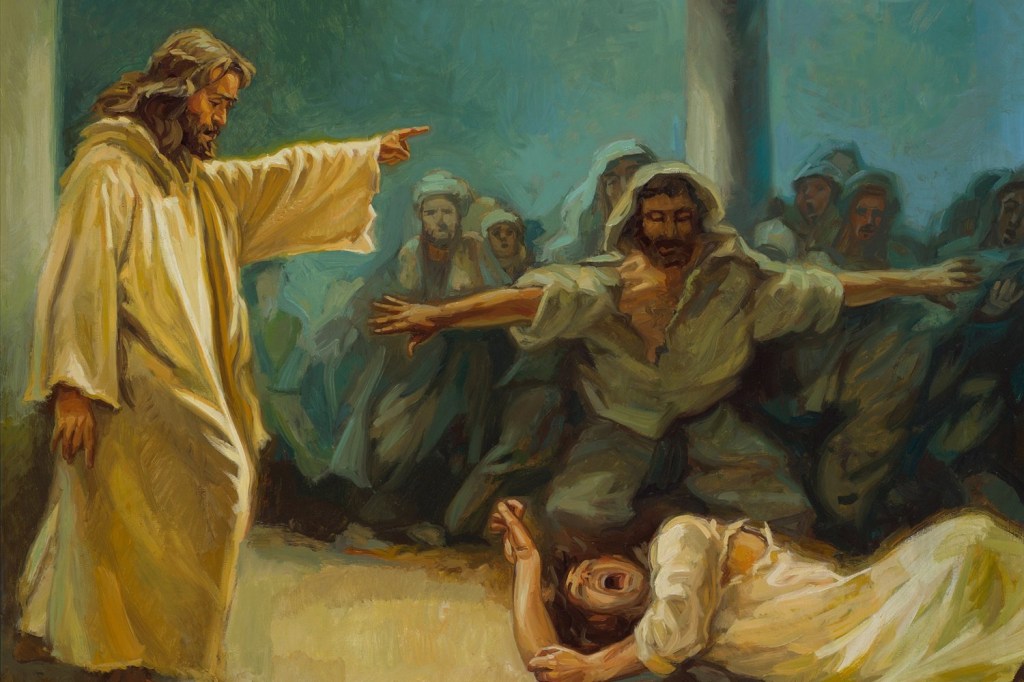

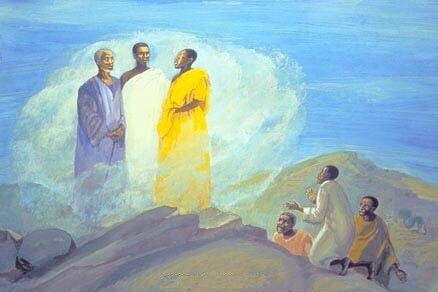

It’s the story of when Jesus took his three closest friends to a mountain, and they had a shared experience of seeing Jesus standing between two of the greats of their people: Moses, to whom God had given the Law to govern the people of Israel, and Elijah, through whom God had established a long line of prophets in Israel (Mark 9:2–8). It’s a story that in Christian tradition is called The Transfiguration.

The word Transfiguration is a strange word. It is not often found in common English usage. It’s one of those peculiar church words, that seems to be used only in church circles. Like thee and thy, holy and righteous, sanctification and atonement … and trinity. These words don’t usually pop up in regular usage!

I looked for some helpful synonyms for the word transfiguration, and found these: change, alter, modify, vary, redo, reshape, remodel, transform, convert, renew … and transmogrify. I am not sure whether that last one gets us anywhere nearer to a better understanding, but some of the others are helpful. Transfiguration is about change, adaptation, and taking on a new shape or size or appearance.

One of the other words offered as a synonym was metamorphose; and that caught my eye, because that word comes directly from the Greek word, metamorphidzo, which is used by Mark in his Gospel, when he tells his account of this incident. “After six days, Jesus took Peter, James and John with him and led them up a high mountain, where they were all alone; and he was metamorphosed before them” (Mark 9:2). Mark then explains that this metamorphosis was evident in that “his clothes became dazzling white”.

The story of the Transfiguration tells of the moment that Peter, James, and John perceived Jesus in a new way. No longer did they see him as the man from Nazareth. In this moment, they see him as filled to overflowing with divine glory. He was not simply the son of Joseph; he was now the divinely-chosen, God-anointed, Beloved Son (9:7).

Jesus brings the heavenly realm right to the earthly disciples. It is what is known, in Celtic Christianity, as a “thin place”: the place where heaven breaks into earthly life.

The disciples had the possibility, in a moment of time, to feel intensely close to the heavenly realm, to stand in the presence of God. They symbolise the desire of human beings, to reach out into the beyond, to grasp hold of what is transcendent—to get to heaven, as that is where God is (see Gen 28:10-12 and Deut 30:12; Pss 11:4, 14:2, 33:13, 53:2, 80:14, 102:19; although compare the sense of God being everywhere in Ps 139:8-12).

This key mountaintop moment contains the words from the heavens about Jesus, “This is my Son, the Beloved; listen to him!” (9:7). These words link back to the initial baptism of Jesus, when the same words were heard (1:11) and forward to the final scene of crucifixion, when a centurion and those with him at the foot of the cross witnesses Jesus’ death, and declares, “Truly this man was God’s Son!” (15:39).

All three scenes contain the foundational statement, recognising Jesus as Son of God, reiterating the words of the unclean spirits in Galilee (3:11) and the man possessed by demons in the country of the Gerasenes (5:7). For, as Simon Peter declares in the pivotal scene at Caesarea Philippi that is also included in this Sunday’s reading, Jesus is “the Messiah” (8:29).

The voice, booming forth from the clouds, “This is my Son, the Beloved; with him I am well pleased; listen to him!” (9:7) seems, at first hearing, to be quoting Hebrew scripture: perhaps the second Psalm, which praises the King of ancient Israel as the one whom God has begotten; or perhaps the song in Isaiah 42, which extols the servant as the one whom God has chosen, or anointed; or perhaps even the oracle in Deuteronomy 18, which instructs the people to listen carefully to the words of the prophet.

Whatever scripture, or scriptures, are here spoken by the divine voice, making this bold declaration from the cloud, it is clear that God has a special task, a special role, and a special place for Jesus. The words of this heavenly voice link this story back to the opening scenes of the story of the adult period in the life of Jesus, and also to a moment towards the end of that adult life.

As this voice is heard, Jesus is on a mountain, with three of his closest followers—and also with two key figures from the past of Israel: Moses, who led the people out of slavery, who then was the instrument for delivering the Torah to Israel; and Elijah, who stood firm in the face of great opposition, whose deep faith bequeathed him the mantle of prophet, as he ascended into heaven.

Mark says that “there appeared to them Elijah with Moses, who were talking with Jesus” (9:4). Matthew reverses the order, placing Moses before Elijah: “suddenly there appeared to them Moses and Elijah, talking with him” (Matt 17:3). Priority, in Matthew’s narrative, goes to Moses. Indeed, Matthew’s concern has been to make as many parallels as possible between the story of Jesus and the story of Moses. The regular reminder that “this took place to fulfil what the Lord has said through the prophets” (Matt 1:22; 2:4, 15, 17, 23) underlines this Mosaic typology.

The covenant given to Moses on Mount Sinai (Exod 19:1–6) is accompanied by the giving of the law (Exod 20:1–23:33), and is later sealed in a ceremony by “the blood of the covenant” (Exod 24:1–8). The scene on the mountaintop, with Jesus and his three disciples, evokes the mystery of the mountaintop scene in Exodus. This story is but one part of the story of Jesus which draws connections with the story of Moses.

*****

The Gospel writers say that Jesus was transformed at that moment. But in this story, also, there is the indication that the friends of Jesus were transformed. That moment on the mountain was a challenge to each of them; the response that Peter wanted to make was seen to be inadequate. Jesus challenged him to respond differently. It was another moment when metanoia, complete transformation, took place. And these disciples did change; yes, it took some time, but these friends of Jesus ultimately became leaders amongst the followers of Jesus, and spearheaded the movement that became the church.

The change, the metanoia, that occurred within Peter, James, and John, spread widely. They faced the challenge head on, and responses, in metanoia. That is mirrored, today, in changes that are taking place in society. Especially, that has been the experience of people over the last few years. We have met the challenge of a global viral pandemic; patterns of behaviour have been modified, as we prioritise safety and care for the vulnerable, and wear masks, sanitise, and socially distance. We have changed as a society.

In the church generally, through the pandemic that hit with such force in 2020, we have changed how we gather, how we worship, how we meet for Bible studies and fellowship groups, how we meet as councils and committees, how we attract people to our gatherings. Transformation has been widespread.

In my own church of these past few years, we worked hard to meet the challenge of reworking our understanding of mission; for across the church, we now see the importance of people from each Congregation engaging with the mission of God in their community as the priority in the life of the church. See

So in each place where people gather as church, there is a pressing need to consider how we might grow fresh expressions of faith, nurture new communities of interest, foster faith amongst people “outside of the building” and outside the inner circle of committed people. It is an ongoing process.

Change is taking place. Change is all around us. Change is the one thing that is constant about life: we are always changing. Sometimes we think that the church doesn’t change, isn’t changing, even resists changing. But that is not the case. Our church is changing. Our society is changing. And the story of the Transfiguration of Jesus encourages us throughout this change.