Since 2019 the Uniting Church has marked a Day of Mourning on the Sunday before 26 January to reflect on the dispossession and ongoing injustices faced by Australia’s First Peoples, acknowledge our shared history and renew our commitment to justice and healing. The Uniting Church has acknowledged our nation’s history through its Preamble to the Constitution, Covenanting Statements, and at many other times through its covenanting journey.

I will be giving this reflection on Sunday 19 January 2025 at the Dungog Uniting Church.

Prayer of Confession

Merciful God, as Second Peoples of this land, whose ancestors travelled and settled in Australia, we acknowledge with sorrow the injustice and abuse that has so often marked the treatment of the First Peoples of this land.

We acknowledge with sorrow the way in which their land was taken from them; the way their their language, culture and spirituality was suppressed.

We acknowledge with sorrow that the Christian church was so often not only complicit in this process but actively involved in it.

We acknowledge with sorrow that in our own time the injustice and abuse has continued.

We have been indifferent when we should have been outraged, we have been apathetic when we should have been active, we have been silent when we should have spoken out.

Gracious God, forgive us for our failures, past and present. By your Spirit, transform our minds and hearts so that we may boldly speak your truth and courageously do your will. Through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Reading Isaiah 62:1–5

For Zion’s sake I will not keep silent,

and for Jerusalem’s sake I will not rest,

until her vindication shines out like the dawn,

and her salvation like a burning torch.

The nations shall see your vindication,

and all the kings your glory;

and you shall be called by a new name

that the mouth of the LORD will give.

You shall be a crown of beauty in the hand of the LORD,

and a royal diadem in the hand of your God.

You shall no more be termed Forsaken,

and your land shall no more be termed Desolate;

but you shall be called My Delight Is in Her,

and your land Married;

for the LORD delights in you,

and your land shall be married.

For as a young man marries a young woman,

so shall your builder marry you,

and as the bridegroom rejoices over the bride,

so shall your God rejoice over you.

Reflection

We all know, I expect, what it feels like to be deeply disappointed; let down, betrayed, forsaken, abandoned. The emotions felt at such a time—emotions of despair and desolation—are named in the reading from Isaiah 62 which we have heard today.

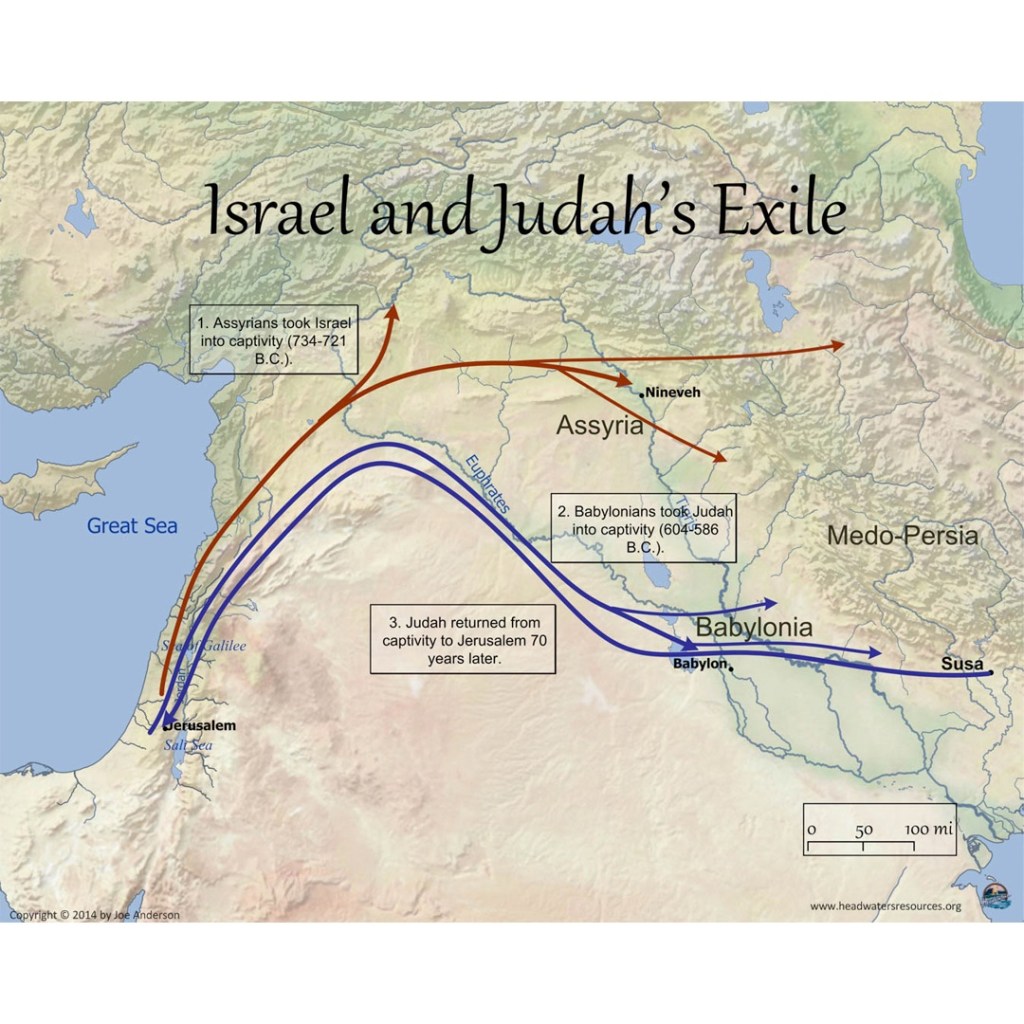

This part of Isaiah comes from the time when the exiles from Israel were returning to their land, leaving behind the difficulties they experienced during their five decades of exile in the foreign land of Babylon. They had returned to a devastated city; it probably looked like the images we have seen on our TVs, from bombed residential areas in Syria and Gaza, to the devastation of mass destruction of buildings from tornadoes in Florida and Louisiana and fires in Los Angeles.

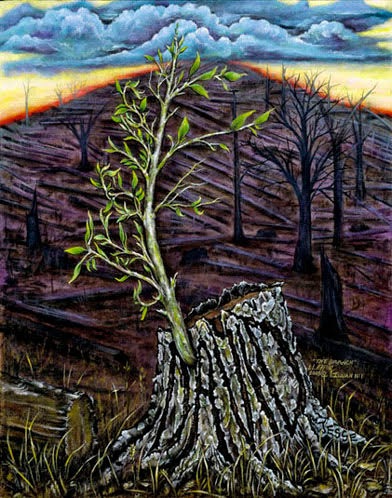

In just such a setting, as the people laboured day and night to rebuild and restore their beloved city, an unnamed prophet speaks out, bringing a word of hope: “You shall no more be termed Forsaken, and your land shall no more be termed Desolate, but you shall be called My Delight Is in Her and your land Married.” The hope that the prophet offers is of a time when desolation is left behind, when the sense of being forsaken has been replaced by loving acceptance and care and belonging; the language of a marriage provides a good analogy.

There are people in our midst, in this town, across this country, who know that sense of desolation and being forsaken. Today we remember them, especially, on a day which the Uniting Church now names as the annual Day of Mourning. On this day, we remember that First Peoples, custodians of this land since time immemorial, caring for creation in their respectful lifestyle and customs, were invaded, colonised, massacred, marginalised, and demonised.

The massacres across the country that took place from the early years of British settlement into the second decade of the 20th century, and the shattering of families by the removal of the stolen children, which lasted well into the 1960s, have given the Gringai, Worimi, Biripi, Wonnarua, and many other peoples cause for ongoing lament and despair. Many still alive today remember what was done to them or to their parents and grandparents. The pain is live.

So on this Day of Mourning, we commit to standing with the First Peoples, acknowledging their pain, sharing their distress (to the extent that we can), treating them respectfully, and committing to work for justice for the First Peoples today. We should know that their pain is still real, present, and powerful.

The referendum held last year offered a ray of hope across the country; fuelled by a campaign of disinformation that played on fears and prejudices, that hope was shattered. The Uniting Church had joined with many other Christian denominations, and leaders of a number of faith communities, to advocate a Yes vote. We have shared in the disappointment of First Peoples, and the sense that this is yet another hurt that they have to bear.

On Australia Day in 1938, a large group of protestors marched through the streets of Sydney, followed by a congress attended by over a thousand people. One of the first major civil rights gatherings in the world—decades before Martin Luther King Jr led massive rallies in the USA—it was known as the Day of Mourning. Following the congress, a deputation led by William Cooper presented Prime Minister Joseph Lyons with a proposed national policy for Aboriginal people. Unfortunately, this was rejected because the Government did not hold constitutional powers in relation to Aboriginal people. That changed in 1967.

From 1940 until 1955, the Day of Mourning was held annually on the Sunday before Australia Day and was known as Aborigines Day. In 1955 Aborigines Day was shifted to the first Sunday in July after it was decided the day should become not simply a protest day but also a celebration of Aboriginal culture. This led to the formation of the National Aborigines Day Observance Committee (NADOC), which later then became NAIDOC, the week in July focussed on remembering Aboriginal people and their heritage.

In 2018, At the Uniting Church Assembly in Melbourne—which Elizabeth and I attended—it was decided to reinstate an annual Day of Mounring on the Sunday before Australia Day. So we stand in a grand tradition, and we stand in solidarity with our brothers and sisters, people who have cared for this land over millennia—many, many thousands of years.

This year, President Charissa Suli and Congress chairperson Mark Kickett invite us “to listen deeply and learn humbly, and bear one another’s burdens; to receive the outstretched hand of friendship offered in grace and hope, and to trust in Jesus, whose reconciling love continues to mend the brokenness within and among us.”

They remind us that “the same ancient Spirit of God which has always been present in these lands has given us ‘a destiny together’ as the body of Christ in this time and place”, and so invite us “to celebrate the immense gift we have in each other [as First and Second Peoples], giving thanks for the transformative and boundless love of Christ which holds us.”

Let us pray.

Gracious God, we know that reconciliation between First and Second Peoples is a challenge. We sense that this must begin with reconciling ourselves in truth and humility with you, our God.

We know that is then that we can do the work of being peacemakers and justice seekers.

So help us to act responsibly and respectfully, to care for one another and to support one another. Amen.

We sing The Aboriginal Lord’s Prayer

Prayers adapted from the resources for the Day of Mourning 2025, https://uniting.church/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Day-of-Mourning-2025_Final.pdf

Artwork by Zoe Belle, Guwa Koa and Kuku Yalanji woman. “The artworks depict the story of Christ’s presence being amongst First Peoples of these lands of his creation for generations. His teachings have long been displayed within the stories, songs, dances and ceremony First Peoples have used them to connect with God as great Creator and teacher for our communities.”