Where is “the fat lady”? We know that, as the saying goes, “it’s not over until the fat lady sings”. So where is “the fat lady”? And has she sung?

Our state and federal leaders appear to think that she has been centre stage, singing her heart out. They are acting as if it is, indeed, over—that the passing of the virus through community spread has diminished, so that we can get back to “business as usual”. (Business being the operative word in government considerations about this matter—business, not health, not wellbeing, but business.)

“It’s not over until the fat lady sings”. It’s a terrible saying, actually, playing on unhelpful stereotypes about body shape and body size. The saying originated, it is often claimed, as a reference to the large-sized women who sang lead parts in operas. (Perhaps the large body size relates to the large lung capacity that is required to perform operatic arias?)

Wikipedia helpfully refers to Wagner’s grand opera cycle, Der Ring Des Nibelungen, and specifically, the last part of that long cycle, Götterdämmerung. It hypothesises that “the ‘fat lady’ is thus the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, who was traditionally presented as a very buxom lady. Her farewell scene lasts almost twenty minutes and leads directly to the finale of the whole Ring Cycle. As Götterdämmerung is about the end of the world (or at least the world of the Norse gods), in a very significant way ‘it is [all] over when the fat lady sings’.”

Others claim that it was a saying first uttered by an American sports commentator, who used the phrase at the end of a university athletics meeting in 1976; or at the end of a 1978 NBA playoff. Or perhaps it is a variant form of the phrase, “It ain’t over till it’s over”, attributed to the famous baseball player, Yogi Berra, at a baseball game in 1973.

Whatever the origin, the saying (in its various forms) is widely known. And, as far as I am concerned, it is very relevant to our current time. For we are now at a point when many people are acting, in relation to the COVID pandemic, as if “it’s over”. I hear this in what people say; I see it in how people behave—low levels of mask wearing, low levels of social distancing, less attention to ensuring that physical contact is minimised, less attention to diligent hand washing and to sneezing into your elbows, and high levels of assuming that we are back to “business as usual”. Goodness, now there is even no requirement that people stay at home when they are sick; saying that people “just need to self-regulate” is a recipe for disaster, especially amongst people who rely on the income they get each week to ensure that they “make ends meet”.

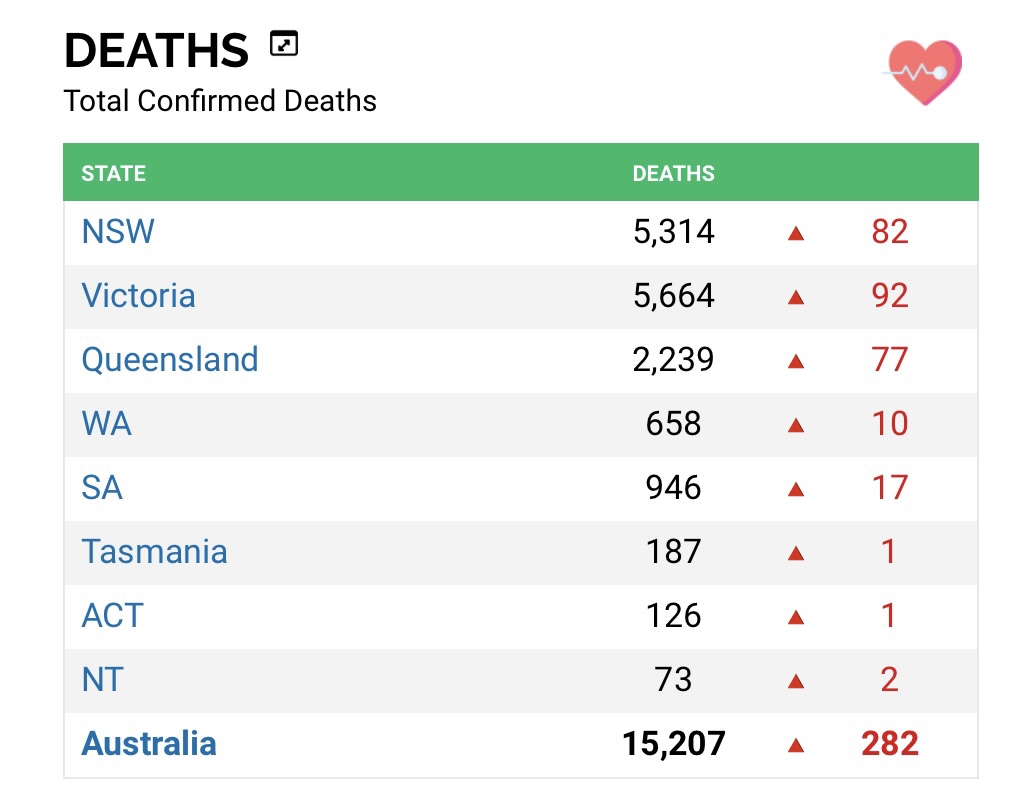

The plain truth is that it’s not over—and that it won’t be over for quite some time. And the costs of the continuing impact of the virus are many. First, we should not forget that deaths from COVID are continuing; they take place at an unacceptable rate; the latest figures show that 323 people across Australia died as a result of COVID in the week ended 21 September—that’s 46 each and every day. A week later, and the number of deaths was slightly lower, at 282, but still at a high level—that is still just over 40 people still dying each week; or 6 a day; or one every four hours.

Week ending 28 September 2022

One person dying every four hours. Think about that. All Ministers and lay people who conduct funerals and provide follow-up support to bereaved families know the deep and enduring emotional impacts that the death of one loved one can incur, spreading across the wider family, friends, and others connected with them through their life. That’s already a significant cost, both in terms of lives taken as well as in terms of ongoing emotional impacts, for one death. Imagine that recurring every four hours, constantly, without pause, day after day. That’s a huge cost in emotional, psychological, and thus medical ways. A huge cost for society.

You can access statistics relating to COVID since early 2020 at https://covidlive.com.au/nt

Second, the consequences of Long COVID continue to be documented as medical studies take place; the Mayo Clinic notes that the long-term effects of “post-COVID 19 syndrome” include “fatigue, fever, respiratory symptoms, including difficulty breathing or shortness of breath and cough, neurological symptoms or mental health conditions, including difficulty thinking or concentrating, headache, sleep problems, dizziness when you stand, pins-and-needles feeling, loss of smell or taste, and depression or anxiety, joint or muscle pain, heart symptoms or conditions, including chest pain and fast or pounding heartbeat, digestive symptoms, including diarrhea and stomach pain! blood clots and blood vessel (vascular) issues, including a blood clot that travels to the lungs from deep veins in the legs and blocks blood flow to the lungs (pulmonary embolism), and other symptoms, such as a rash and changes in the menstrual cycle”.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/in-depth/coronavirus-long-term-effects/art-20490351

That’s a wide range of issues which can each be very significant, causing longterm difficulties, and in some cases, contributing to an early death. That’s a second major cost.

Third, rates of absenteeism provide a striking indicator that the impacts of the pandemic are still with us. In February, the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that “more than one in five (22 per cent) employing businesses had staff who were unavailable to work due to issues related to COVID-19”

https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/staff-absent-22-businesses-due-covid-19

In April, the Australian Financial Review reported that “absenteeism rates sitting 33 per cent higher than long-term averages, analysis of MYOB’s payroll data reveals”.

https://www.afr.com/work-and-careers/workplace/havoc-as-absentee-rates-surge-by-a-third-20220408-p5ac52

By July this year, this had grown to “absences already running at 50 per cent above average levels, as the highly contagious BA.4 and BA.5 variants drive a new wave of infections and hospitalisation”.

https://www.afr.com/policy/health-and-education/bosses-brace-for-a-month-of-record-sick-leave-20220710-p5b0h9

The media delighted in showing lengthy lines at airports because of staff shortages; perhaps many of us have experienced slow service at local cafes because of the same reason. The cost of extra sick leave payments is just one component of the cost in this regard. It is said that during pre-pandemic times, the “regular rates of absenteeism” cost Australian businesses around $32.5 billion a year. With increased rates of absenteeism, that cost has surely risen.

Of course, now that the requirement to isolate at home whenever a person is symptomatic has been removed, we will surely see further disruption to business enterprises—since people dependent on their wage will go to work when “just a little bit off”, and if infected with the virus, they may be infectious, and thus may well spread illness to their fellow workers—thus resulting in more people off, more time lost. I can see this. Why can’t our leaders see this?

All of which leads me to the conclusion that “it’s not over until it’s not over”—and clearly, “it’s not yet over”. We need to ensure ongoing protection from the virus in our day to day life. Of course, one hugely important way to provide strengthened protection against the COVID-19 virus is to be vaccinated— and to have each of the “booster doses” as they become available. It’s clear that widespread vaccination has contributed to a slowing of the spread of the virus.

Sadly, however, the rate of deaths due to COVID continues to be of concern. That’s simply because people who are more at risk of infection—the elderly, those with compromised immune systems, those with multiple medical conditions, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders—are thereby more likely to have a bad response to the virus, with more medical complications, and higher death rates.

I’ve found a recent study which sought to compare the efficacy of vaccination amongst healthy people with the efficacy amongst immunocompromised people. It measured the level of seroconversion, which is the capacity of the system to repel the virus. The study concluded that “the immune response to the influenza vaccine might not be as strong in immunocompromised patients, yet they appear to derive some benefit from vaccination. These findings reflect what is now being experienced with covid-19 and vaccination.”

See “Efficacy of covid-19 vaccines in immunocompromised patients: systematic review and meta-analysis”, https://www.bmj.com/content/376/bmj-2021-068632

All of which means that vaccination is a wise move, but it in no way guarantees that a person once vaccinated will definitely not suffer ill effects; and a person with medical vulnerabilities, such as having an immuno-compromised system, will still be vulnerable to illness, serious medical,complications, and death.

Which means that we need to continue all those precautions that we learnt in early 2020: wear a mask; practise good hygiene; wash your hands; sanitise with alcohol-based hand rubs; maintain social distancing; don’t touch your face; cover your mouth or nose with your arm, not your hand, when you cough or sneeze; stay t home when you are sick; close the toilet lid before flushing. All of these things, even though they are not “mandated”. All of these things, because it is just common sense to continue to take great care. Because it’s not over. Not by a long shot. There is no fat lady, not yet. It’s not over.