The following “transcript” reports an imagined interview that I conducted with “Luke”, the person claimed to be the author of the third Gospel and its sequel, Acts. (Of course, what the “Luke” of this “interview” articulates is what I have come to think about him and how he saw things.) Wouldn’t it be great if we did have the transcript of an actual interview with the author of this Gospel? Well, for the moment, we will just have to settle for this. Enjoy ………

What motivated you to write about Jesus?

I thought I had something to offer, in short. Lots of stories about Jesus have been passed on by word of mouth for some years now; there have been collections made of his best sayings and parables, as well as sets of well-known miracles. There is also an account of how he met his death (some call it “the passion of Jesus”) which has obviously been put together by someone who knew the psalms, especially the psalms of the righteous sufferer.

But beyond hearing these oral accounts, I have become aware more recently that some others have written about Jesus. I wanted to provide an extended version of the story of Jesus that highlighted both his connection to his Jewish heritage, and also how what he said and did provided the foundation for the development of the church. To achieve this I actually had to write a second volume, which some have called “the acts of the apostles”. But because I am convinced that the whole life of Jesus was guided by the Spirit, and that has continued on into the church, I prefer to think of it as “the acts of the holy spirit”.

At any rate, I wanted to provide my personal understanding of this important figure and the movement that he instigated. For everything that took place, I believe, is on accord with the predetermined plan of God. This plan involves both the very good things that took place, as Jesus drew people to him and as the movement spread across the world, as well as things that seemed to be quite a setback, such as the crucifixion of Jesus, the stoning of Stephen, and the trials of Paul. They are all part of this overall plan. We know that God confirmed all of this by raising Jesus from the dead—and by blessing the spread of the movement as the number of disciples grew—why, even some priests became followers!

So I think that my account, which is orderly and accurate, will stand well alongside these other works that I know of. Indeed, it is presented as a consistent work with an overarching theme of divine providence, which has been a favoured theme of numerous historians in the past, and much considered by philosophers in every age. So I am quite sure that the corrections and expansions that I offer in my work, as well as the deepened theological understandings that it contains, are all important to put on the public record.

Finally, I must express again my thanks to my patron Theophilus, whom I have acknowledged in the prefaces to each volume of my work. I am indebted to him for his provision of lodging, access to his wonderful library, and material support during the months when I was researching and writing my two volumes. I am most grateful to him for all of this. He has served me well as a fine patron.

Where did you get your information from? How well did you know Paul, for instance?

Well, I stated right at the start of my work that I was drawing from people who were actually with Jesus and were eyewitnesses of what took place, right from the very first. These people subsequently made sure that the words of Jesus and stories about him were remembered and passed on by word of mouth. The remembrances that they provided were very helpful, because I didn’t actually see anything in person of what I wrote about.

As well as stories from these eyewitnesses, I also drew from the recollections and writings of those who were part of the growing movement that developed in the years after the time of Jesus, as word spread around the various provinces of the Roman world—and beyond, down to Ethiopia, even. It has been important for me to receive and assess a whole host of stories from these “servants of the word”, as I call them. Even if some of them were, well, a little rough and unformed. So, I have worked diligently to put them in an order that conveys the truths that Jesus and the apostles each in turn spoke. All inspired by the Holy Spirit, of course.

Paul? Well, I’ve heard of him, of course; who hasn’t? Quite a character he was, it seems. Rather divisive, it is said; people either loved him or hated him. But I have never met him. Never travelled with him. Never heard him speak. Just heard about him, where he went, what he did, who he travelled with, what he said; and what eventually happened to him when the might of the Roman Empire caught up with him, despite his best efforts to defend himself. So I have tried to capture this in my second volume.

I have heard that Paul was quite a letter writer—although for myself, I haven’t seen many of his letters. What I have read seems to have been quite sharp and polemical. Perhaps that reflects his rabbinic upbringing at the feet of Gamaliel; he learnt how to argue hard! But I am not sure how helpful his polemical stance has been for the development of the movement.

I know that Paul was a faithful follower of Jesus in the years after his conversion, so I have given him the benefit of the doubt, making sure that any of his words that I included were consistent with what the apostles in Jerusalem had preached in earlier years. Harmony and consistency across the movement is important, I believe, despite the conflicts we have experienced over the years. That’s why I provided a careful account of the council held in Jerusalem in my second volume, when a major tension within the movement was resolved by the leaders coming together—and the spirit, of course.

It is said that you are a doctor. Where did you learn your medical skills?

Ah, yes, this old chestnut. So let’s be clear: I have no medical qualifications. I have never provided trained medical assistance to anyone. I do, however, know about medical things—like anyone who takes the time to read and think about these things does. I know technical medical terms. I know how healers operate. Indeed, I had to learn about this in order to give an accurate portrayal of Jesus as he went about healing people.

However, the medical insights you can see in my work don’t come from my own particular training or experience. No, it’s because I have read widely in literature that includes technical discussions of ailments and illnesses and healings, that I know about these things. As would any well-read person, I assume.

But this whole matter has not been helped, no doubt, by the fact that there are references to a person with the same name as me in letters associated with Paul. Although I haven’t seen these letters, I am told that in one letter written while he was imprisoned in Rome, Paul sends greetings from “Luke the beloved physician” to Nympha and Archippus, and those in their household gatherings.

That’s all well and good, but I can assure you that this particular person is not me. It’s simply a case of sharing the same name—a common-enough occurrence. I mean, how many people do you know named Paul? Or John? Or Mary? As I said before: I have never travelled anywhere with Paul. So I am not a physician, as this particular companion was. Although I am quite happy to be known as “beloved”. Someone amongst the followers of Jesus surely deserves this appellation!

Your story about Jesus is often called “the Gospel for the Gentiles”. What do you think about this description?

It’s true that I really wanted to offer an explanation to the wider world in which we live—beyond the Judaism of the land of Israel itself—about the relevance and the importance of the movement that Jesus initiated for everyone in that wider world. He fulfils the prophetic word that “all flesh” shall see the salvation that God is bringing through Jesus.

So I am undertaking the process that some call “apologetics”; writing a work that “speaks out” the meaning of the faith (that’s what “apologetics” means), reaching across the divisions of language and culture to explain a message from one context in a way that makes sense in another context. Like others who have done this before. I try to anticipate the difficulties and objections that might be raised, and try to provide ways that people of the Way can respond to these objections.

Yes, it is true that Jesus was a Jewish man, from Galilee, who taught in parables and debated Torah interpretation with the scribes, and went on pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem—presumably to offer sacrifices to the Lord God. There’s no doubting his Jewishness. Nevertheless, I am certain that his teachings about the reign of God are applicable to people who do not know the God of Israel. So my two volumes show how the words of this Galilean prophet offer hope and salvation to Gentiles across the world.

And, you know, for a long time now, Jews have lived in many places beyond Jerusalem. There are many Jews that live in diaspora (in the Dispersion), and they have done so ever since the time of the Exile, when the people of Judea were taken away into captivity by the Babylonians. Many of them stayed where they were taken, married locals, learnt the language, planted vineyards, and established family businesses. And they emigrated elsewhere around the Mediterranean Sea—not just back to Israel, but to Egypt and to many other provinces which are under Roman rule.

So those of us who follow the Torah while we live in Diaspora have a particular interest in the teachings and the vision of this Galilean prophet.

Wait a minute: you said “those of us who follow the Torah while we live in Diaspora”, did you? But I thought you were a Gentile!

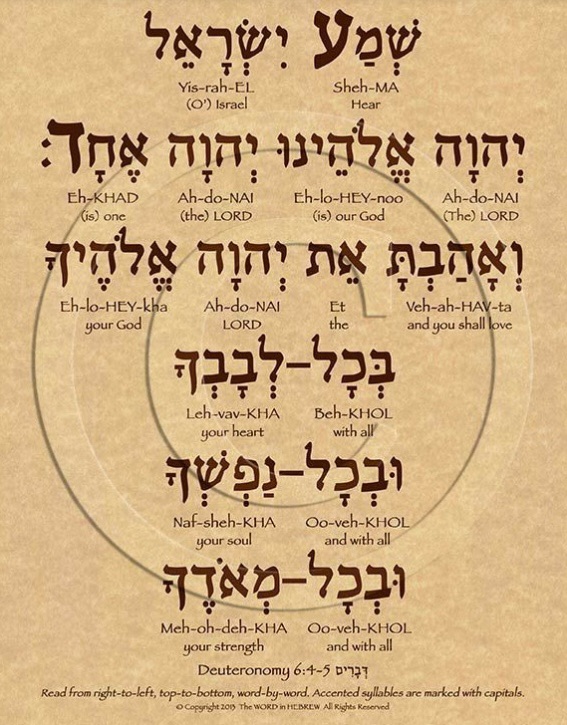

Yes, that’s a common misunderstanding. Just because I speak and write Greek, live outside Israel, in a strongly hellenised city amongst people who continue to worship many gods, and participate in public ceremonies along with other well-to-do citizens, does not mean that I am not one who keeps Torah. I believe in the one God, I follow the high ethical standards set out in Torah, and I take part in gatherings in the synagogue as often as I can, given my other civic duties.

Some people say that I am a “godfearer”, thinking that I am a Gentile who is attracted to the synagogue because of its high ethical standards. And that makes for a fairly easy transition to follow the way of Jesus, I must admit. I actually included a number of such characters in my second volume, you know: Cornelius, Lydia, some men attached to the synagogue in Antioch, Titius Justus and Crispus in Corinth, some leading women in Thessaloniki, and a group of some significant women and men in Beroea, for instance.

However, I was born, in diaspora, into a Jewish household. I was taught Torah as well as reading the literature of Greece and Rome. I have read from the scroll in the synagogue, just as I report Jesus doing—although I have never said “today this scripture has been fulfilled”, as he did! And yes, since you undoubtedly want to know, I am circumcised. I can read Hebrew, obviously, and can also speak our local language of Aramaic, just as Jesus did. And I am so pleased that I could report how Jesus, speaking in the synagogue after he read from the scroll, affirmed that God wants “release to the captives, recovery of sight to the blind, [and] to let the oppressed go free”, just as the prophet declared.

But all of this has not stood in the way of my reading and learning from Greek philosophers and historians, enjoying plays and poems by Greeks and Romans, as well as studying Torah and the teachings offered in the synagogue. I am a Jew, but I suppose you would say a very hellenised Jew. In fact, if there’s anyone in the work that I have written that I admire, and who I identify with—apart from Jesus himself—is Apollos of Alexandria. He’s quite cosmopolitan, well educated, and has a way with words. He was raised a Jew but has known about the Way of Jesus since the early days of John. I’d like to think I am rather like him.

If you had your time over again, what would you do differently with the story that you wrote?

There’s a couple of minor glitches that eagle-eyed readers of my work have drawn to my attention. The reference made by the Pharisee, Gamaliel, to the revolutionary Theudas was a slip of the pen: Gamaliel was speaking in the early 30s, but Theudas was active in the 40s. His uprising, which did not last long, was some years after the speech that I placed on the lips of Gamaliel! And I would remove the reference to the census that took place in Syria under Quirinius, as this confuses the matter. Some of my critics have said, wasn’t Jesus born when Herod was still alive? So I regret that error.

I think I should also clarify that the description of the Temple being surrounded and destroyed by the Roman army that I placed on the lips of Jesus was actually informed by my own knowledge of those events, as I have learnt about it from others closer to that event itself. I shouldn’t have had Jesus speak in such detail. I know that he was a prophet, and that he saw the ways that our people had become disobedient, but I don’t think his prophetic insight stretched quite as far as the specific details I provided.

And in contrast to those who say that I have confused the order of things in the account of the last supper that Jesus had with his disciples, I maintain that I got it right. A blessing over a cup of wine comes before a blessing over the bread—and then other blessings follow, including another blessing over another cup. At least, that’s the practice that I am used to.

In the same vein, to those who have criticised me for retaining the saying by Jesus about how “this generation will not pass away until all things have taken place”: I simply note that he said it! I think I have made it clear in other speeches of Jesus just how this expectation has already been modified and altered within the movement. Such reinterpretation is going on all the time!

Any final comments?

Thanks for giving me the chance to talk about my work, to explain some key things, and to set a few things right. I appreciate that. I hope everyone who reads it enjoys it and learns from it.

*****

What did “Theophilus” think about the work that “Luke” wrote? I have also written a series of Letters to Luke in which I imagine how his writings might have been received. You can find the links to these six letters at

*****

The above “interview” and these “letters” draw on the research on Luke and Acts that I have undertaken over the years, which has been published as:

The plan of God in Luke—Acts (CUP 1993)

“The plan of God in Acts” in The Witness of the Gospel: the Theology of Acts (ed. I.H. Marshall and D. Peterson; Eerdmans, 1998)

At table with Luke (UTC Publications, 2000)

A commentary on “The Acts of the Apostles” in the Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible (ed. J.D.G. Dunn and John Rogerson; Eerdmans, 2003)

“The Gospel of Luke” in the Cambridge Companion to the Gospels (ed.Stephen C. Barton and Todd Brewer; CUP, 2006)

Many of the blogs on this website also reflect this continuing research.