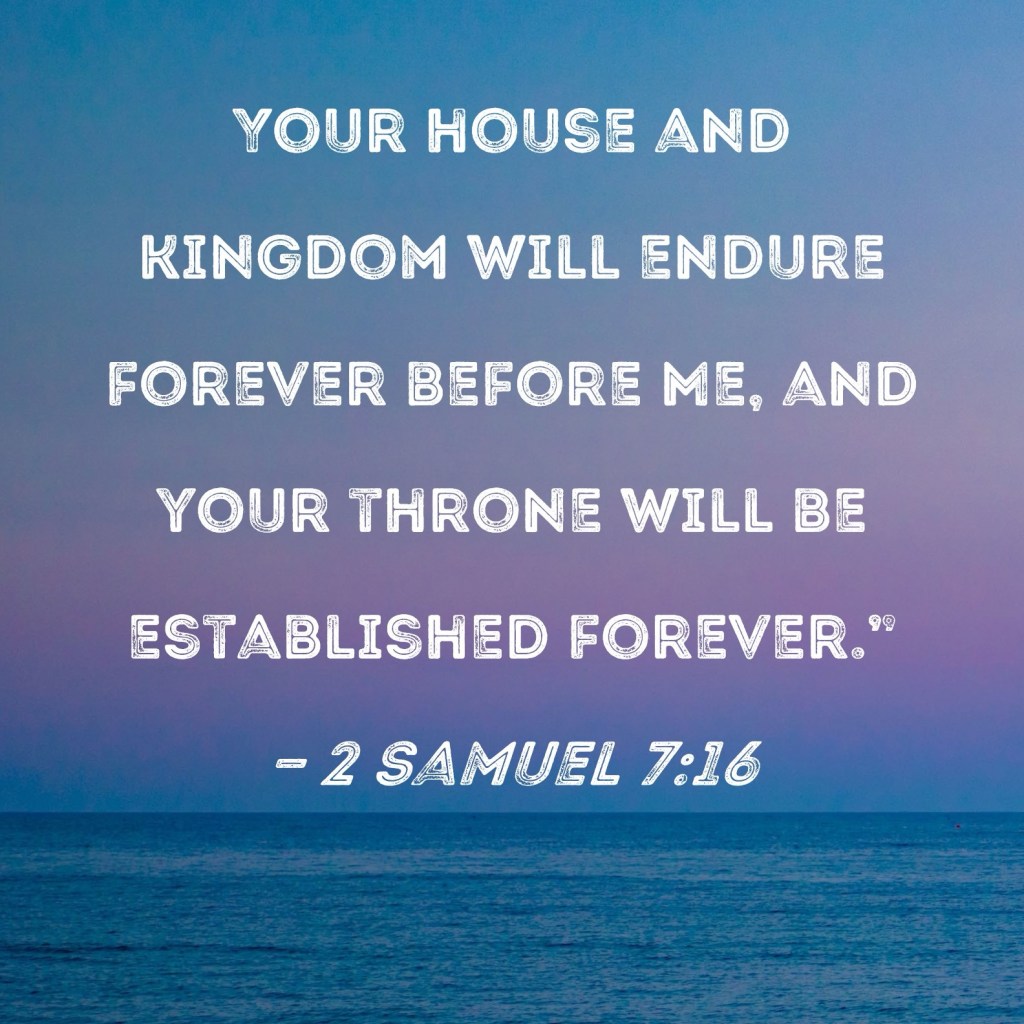

“A king forever”. That is the promise of these well-known words in 2 Samuel 7, which we will hear and reflect on in worship this coming Sunday. They are significant words for Jews; they are also significant words for Christians, for they have informed the way that followers of Jesus would talk about him. The words are given initially to David, only the second king of Israel, but the one who would provide descendants to sit on the throne for half a millennium.

The words of the prophet Nathan, given to him (as he says) by the Lord God, are reported and remembered over those centuries as validation of the power of those kings, even though so many of them “did evil in the sight of the Lord” (as later verses in the historical narratives of Israel report). God stood by those leaders over many generations, consistently reminding the people of their responsibility to adhere to the covenant, affirming them at moments when their faith is evident, and rebuking them at times when that is not the case.

These words have been remembered further by Christians, who see that in Jesus, God has sent “the King of the ages” (1 Tim 1:17), to whom “belong the glory and the power forever and ever” (1 Pet 4:11; also Rom 16:26; Eph 3:21). This is in accord with the “eternal purpose that [God] has carried out in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Eph 3:11), to lead believers to “eternal life” (Luke 10:25; John 17:3; Rom 5:21; 6:23).

Of course, in those words which Nathan speaks to David, we recognise the play on words that occurs. David understands God to be promising a “house” which is “a house of cedar” (v.7), but God actually intends to establish “offspring after you … his kingdom” (v.12).

Writing in With Love to the World, Mel Pouvalu observes that “The word “house” is used fifteen times in 2 Samuel 7, where it has three different meanings. It refers to David’s palace (vv.1–2), to the temple of the Lord God (vv.5–7, 13), and then to David’s dynasty (vv.11, 16, 18–19, 25–27, 29).” She continues, “It is important to see that our ways are not God’s ways, even if we mean well. The story promises a stable future for generations to come, and these narratives are reminders that God will always be seeking us.”

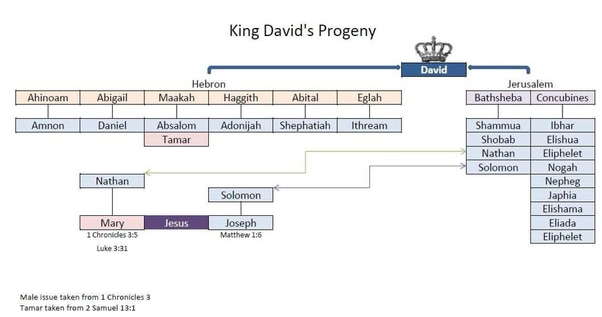

The motif of a kingdom that lasts “forever” is linked both with the affirmation that there will be a king “forever”, and also with the belief that the covenant with Israel will last “forever”. That there will be a king “forever” is integral to God’s promise to David that “your throne shall be established forever” (2 Sam 7:16), repeated by the Chronicler, “when your days are fulfilled to go to be with your ancestors, I will raise up your offspring after you, one of your own sons, and I will establish his kingdom … and I will establish his throne forever” (1 Chron 17:11–12).

The kingdom that will last “forever” is introduced by God’s words in 2 Samuel 7, where God promises David that “your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me” (2 Sam 7:16). The Chronicler also repeats this promise, quoting God as saying of David, “I will confirm him in my house and in my kingdom forever, and his throne shall be established forever” (1 Chron 17:14).

Affirmation of a covenant that will last forever is found in a number of psalms. “The Lord our God … is mindful of his covenant forever, of the word that he commanded, for a thousand generations, the covenant that he made with Abraham, his sworn promise to Isaac, which he confirmed to Jacob as a statute, to Israel as an everlasting covenant” (Ps 105:7–10).

The covenant is noted in a number of psalms. “The friendship of the Lord is for those who fear him, and he makes his covenant known to them”, sings the psalmist (Ps 25:14). “I have made a covenant with my chosen one, I have sworn to my servant David”, God sings in another psalm; “I will establish your descendants forever, and build your throne for all generations” (Ps 89:3–4).

In this same psalm, God affirms that, even if the children of David “forsake my law and do not walk according to my ordinances”, God will punish them, but “forever I will keep my steadfast love for him, and my covenant with him will stand firm … I will not violate my covenant, or alter the word that went forth from my lips” (Ps 89:28, 34). That covenant is to last “forever” (Ps 111:9).

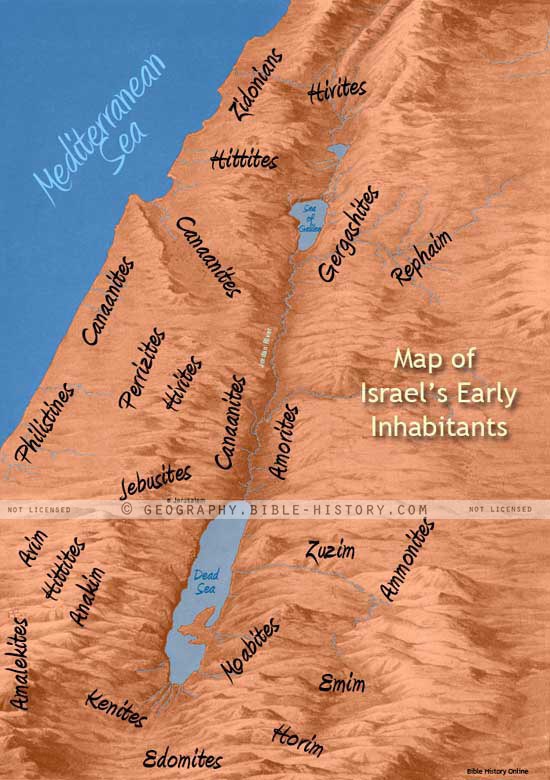

The ultimate message, then, is that God will stand by the leaders of Israel, punishing them, forgiving them, loving them at each step along the way. A promise to sustain a king and a kingdom “forever”, by virtue of a covenant that lasts “forever”, undergirds this reality for the people of Israel. The modern nation state of Israel has adopted this confident assertion, although without any critical appreciation of the context and the purpose of this promise in antiquity. The dreadful results of this unthinking adoption of the mantra that “God is always with us” is playing out in the many deaths, injuries, and sadness that is taking place in Gaza, even today.

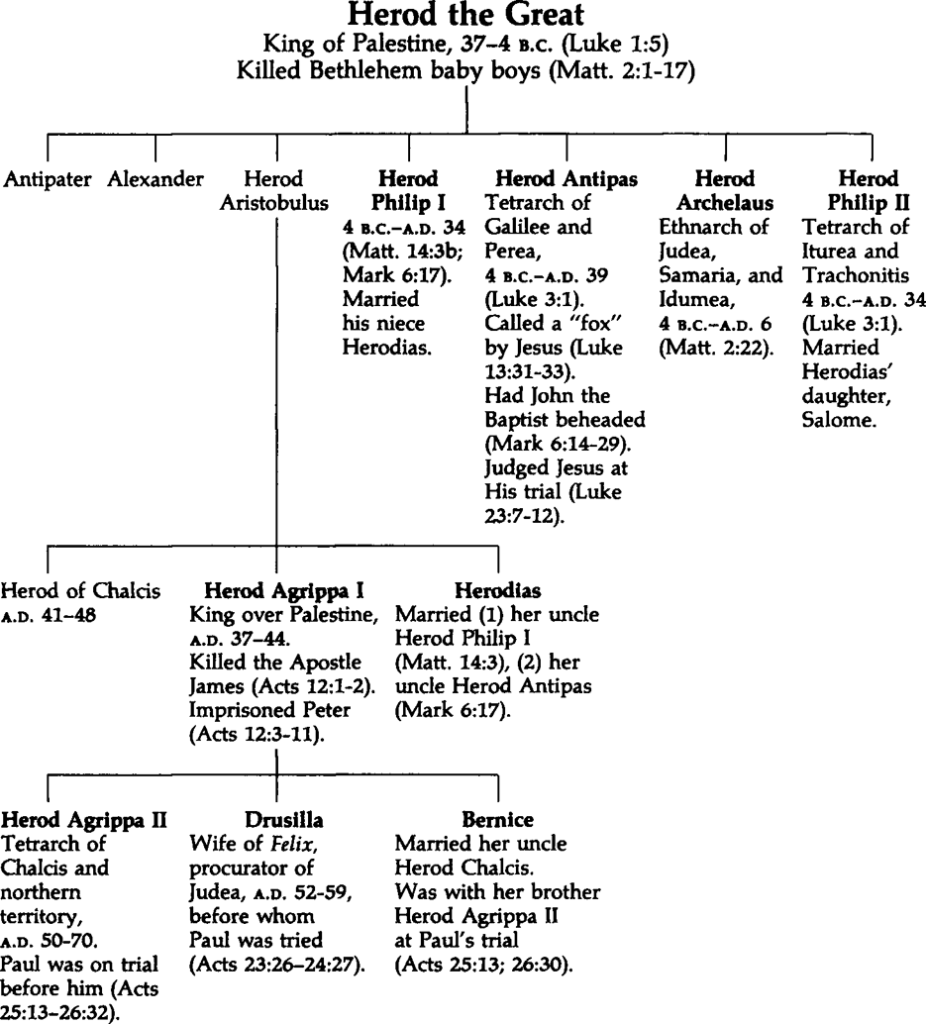

Of course, in the traditional understanding of Christianity, the “forever” component has been taken up in the application of 2 Samuel 7 to Jesus of Nazareth. Jesus is acclaimed as “Son of David” in the Synoptic Gospels (Mark 10:47–48; 12:35; Luke 3:31; 18:38–39; and especially in Matt 1:1, 20; 9:27; 12:23; 15:22; 20:30–31; 21:9, 15; 22:42). This claim is also noted at John 7:42; Rom 1:3; 2 Tim 2:8; Rev 3:7; 5:5; 22:16). The heritage of David lives on in these stories.

This particular son of David, as Christian understanding develops, was understood to be king “forever”; “he will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end” (Luke 1:31–33). The covenant that he has renewed and enacted with the people of God is “forever” (Heb 9:15; 12:20); and the kingdom that he proclaimed and for which we hope will also be “forever” (2 Pet 1:11).

In the late first century document that we know as letter to the Ephesians, for instance, the resurrected Jesus is seen as seated at the right hand of God “in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion, and above every name that is named” (Eph 1:20–21). That place of authority for Jesus is envisaged as stretching into eternity, “not only in this age but also in the age to come” (1:20), and as encompassing all places, for God “has put all things under his feet and has made him the head over all things” (1:22).

The global and eternal rule of Christ is here clearly articulated. The statement by the writer that God “seated [Jesus] at his right hand in the heavenly places, far above all rule and authority and power and dominion” (1:20–21) has inspired the development of the imagery of Christ as Pantocrator (Greek for “ruler of all”) in Eastern churches, both Orthodox and Catholic.

Jesus Christ Pantocrator; from a mosaic in the Hagia Sophia mosque (formerly a church), in Istanbul

This line of thinking has culminated in the festival of the Reign of Christ, which has been celebrated in the Roman Catholic Church since it was introduced by Pope Pius XI in 1925. It has since been adopted by Lutheran, Anglican, and various Protestant churches around the world, and also, apparently, by the Western Rite parishes of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia.

1925 was a time when Fascist dictators were rising to power in Europe. I have read that “the specific impetus for the Pope establishing this universal feast of the Church was the martyrdom of a Catholic priest, Blessed Miguel Pro, during the Mexican revolution”; see Today’s Catholic, 18 Nov 2014, at

The article continues, “The institution of this feast was, therefore, almost an act of defiance from the Church against all those who at that time were seeking to absolutize their own political ideologies, insisting boldly that no earthly power, no particular political system or military dictatorship is ever absolute. Rather, only God is eternal and only the Kingdom of God is an absolute value, which never fails.”

The scriptures puncture the pomposity of powerful kings, and subversively present Jesus as the one who stands against all that those kings did. This festival provides a unique way of reflecting on the eternal kingship of Jesus. It offers a distinctive way for considering how the kingship bestowed upon David has been understood to last “forever”.

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.

You can subscribe on your phone or iPad via an App, for a subscription of $28 per year. Search for With Love to the World on the App Store, or UCA—With Love to the World on Google Play. For the hard copy resource, for just $28 for a year’s subscription, email Trevor at wlwuca@bigpond.com or phone +61 (2) 9747-1369.