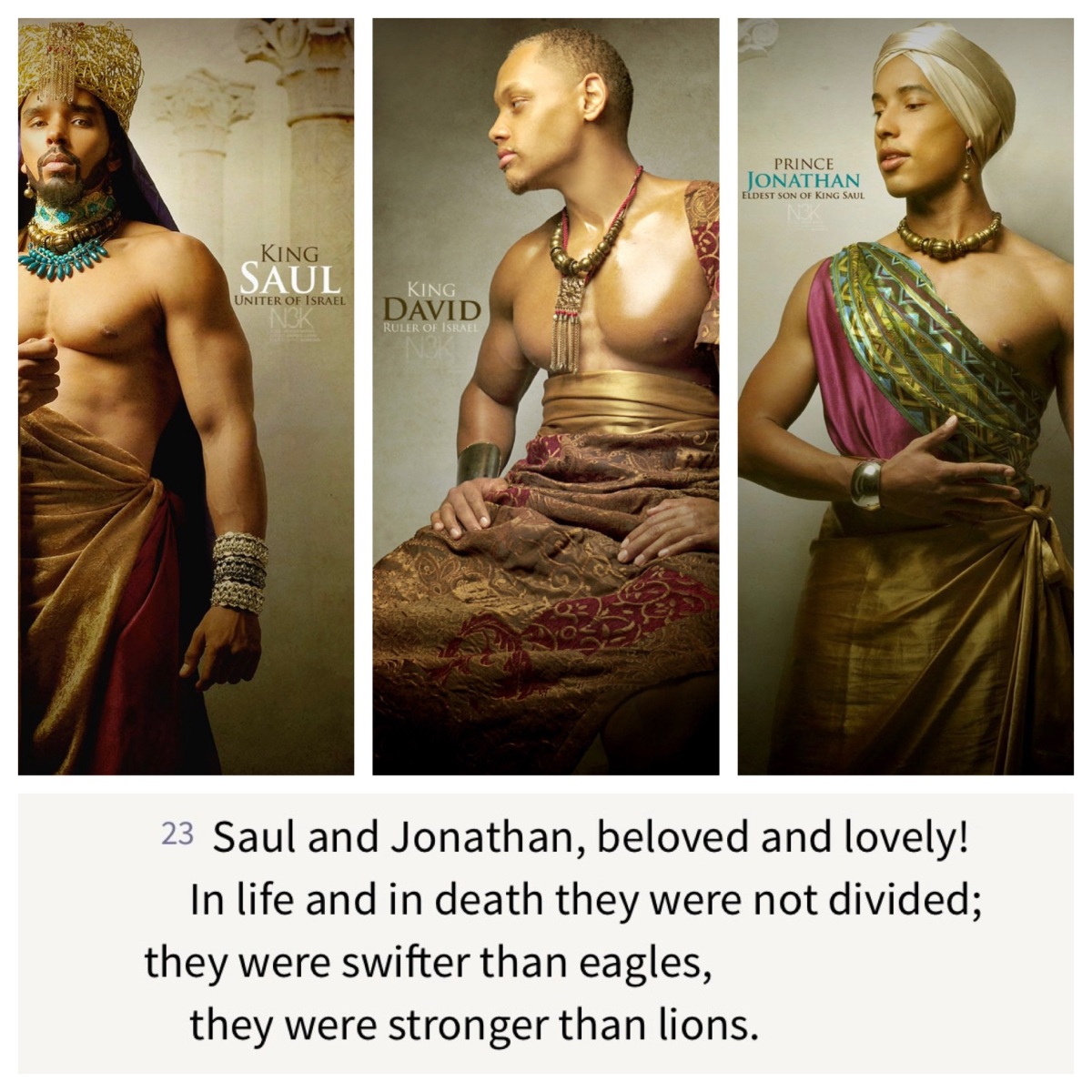

For the Hebrew Scripture passage this coming Sunday, the lectionary offers a passage (2 Sam 1:1, 17–27) that has been the subject of controversy. The passage is a lament, sung by David on the death of Jonathan, the son of Saul. The controversy revolves around the nature of the relationship between David and Jonathan. That relationship has an interesting history, and comes to a full expression in this passage.

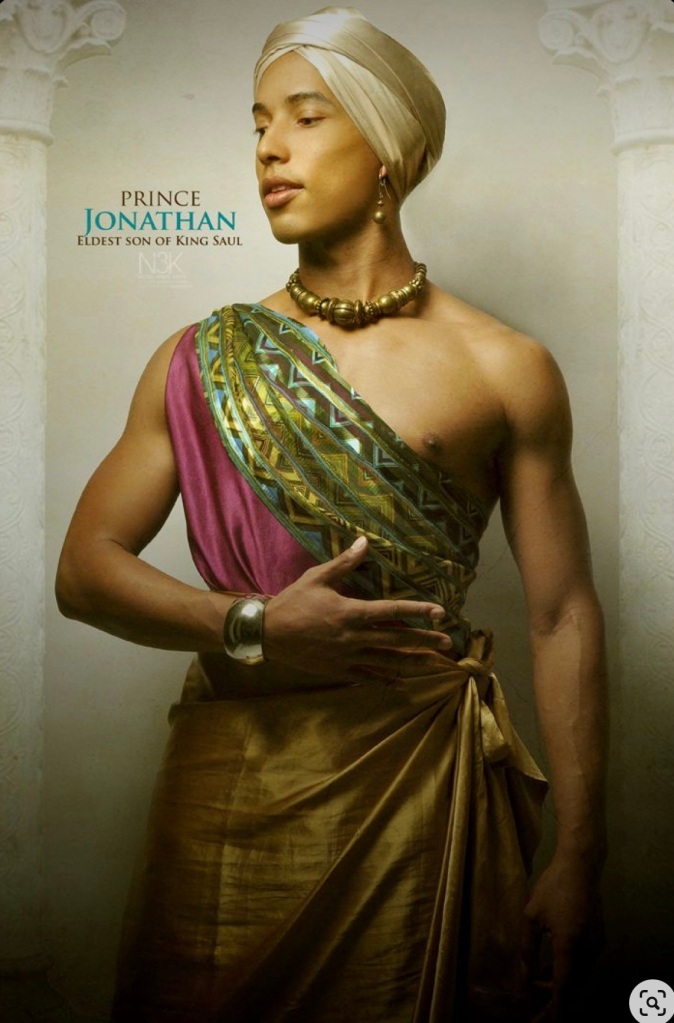

We first meet Jonathan, son of Saul, when he led a thousand troops, defeating the Philistines in a battle at Gibeah (1 Sam 13:2–3). He was successful in a number of subsequent battles; Jonathan was renowned for his skill with bow and sword (2 Sam 1:22). David had met him after he had slain the Philistine giant, Goliath (1 Sam 17); the narrator of this book observes that “the soul of Jonathan was bound to the soul of David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul” (1 Sam 18:1).

What Jonathan does is striking, as he “stripped himself of the robe that he was wearing, and gave it to David, and his armour, and even his sword and his bow and his belt” (1 Sam 18:4). As Saul’s firstborn son, Jonathan might have expected to have inherited the crown from his father; instead, he divests himself of all the royal trappings and places them on the one anointed as king, his friend David. The imagery has political significance. But does it also have a personal dimension?

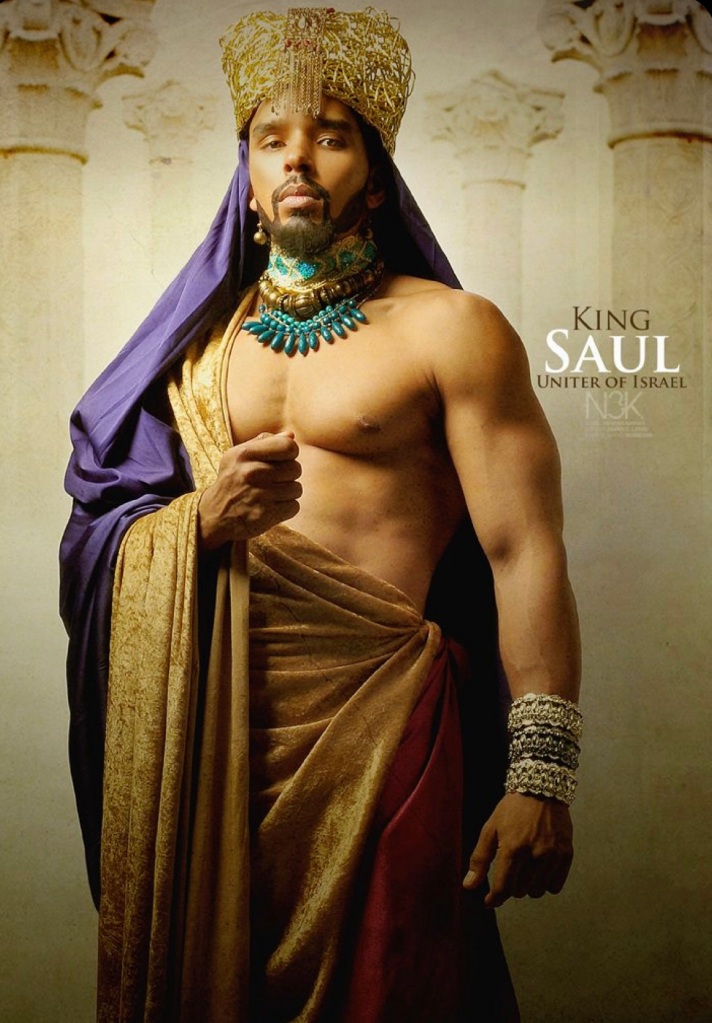

The friendship between David and Jonathan continued through various battles until, eventually, “the Philistines overtook Saul and his sons; and the Philistines killed Jonathan and Abinadab and Malchishua, the sons of Saul” (1 Sam 31:2). Saul himself was wounded (1 Sam 31:3) but then, sensing the inevitable, he “took his own sword and fell upon it” (1 Sam 31:4).

With the death of Saul and the earlier death of Samuel (1 Sam 25:1), a new era was beginning. David, previously anointed as king over Israel by Samuel (1 Sam 16:13), was now also anointed as king over Judah (2 Sam 2:4). A united monarchy would continue for decades.

The relationship between Jonathan and David has been the cause of renewed enquiry in recent decades. Was the love expressed by these two men for one another simply “bruvver love”, as best mates; or was it deeper and more controversial than this? Loving relationships between people of the same gender are increasingly accepted in today’s world, at least in Western societies. Was that what was happening between the king and the former king’s son?

The “great delight” that Jonathan had for David (1 Sam 19:1) and his complete trust in him (1 Sam 20:4) leads them to form a covenant together on the basis that Jonathan loved David “as he loved his own life” (1 Sam 20:16–17).

Entering into a covenant with another person is a serious undertaking. Abraham and Abimelech covenant together at Beersheba, so that Abraham can live peaceably amongst the Philistines (Gen 21:22–34).

Laban and Jacob covenant together at Galeed to consolidate the two-decades-long relationship between the two men (Gen 31:43–55). David made a covenant with the elders of Israel at Hebron when he was anointed as king over Israel (2 Sam 5:1–5). Jehoida made a covenant with the captains of the Carites and of the guards, so that his son Joash would be protected and ultimately proclaimed king (2 Ki 11:4–12).

And, of course, the Lord God made a covenant with Noah and the whole of creation (Gen 9), and then renewed that covenant a number of times—with Abram (Gen 17), with Isaac and with Jacob (Lev 26:42), with all Israel through Moses (Exod 19, 24), under Joshua (John 24), and then with David (2 Sam 7) and various of his descendants. All major exilic prophets look to a time when God will renew the covenant with the people back in the land (Isa 55–56; Jer 31:31–35; Ezek 16:59–63; 37:24–28). The people of Israel were bound to the Lord God in covenant; the steadfast love that God shows towards Israel is an expression of that covenant.

Human-to-human covenants were political tools, creating alliances amongst the leaders of various tribes or nations of people in the ancient world. The covenant formed between Jonathan and David clearly has political implications. Jonathan, the son of Saul and rightful heir to the throne, hands over his armour to David (1 Sam 18:4) to signal that he is ceding power to David as the next king. The scene is infused with the political freight of an ancient covenant.

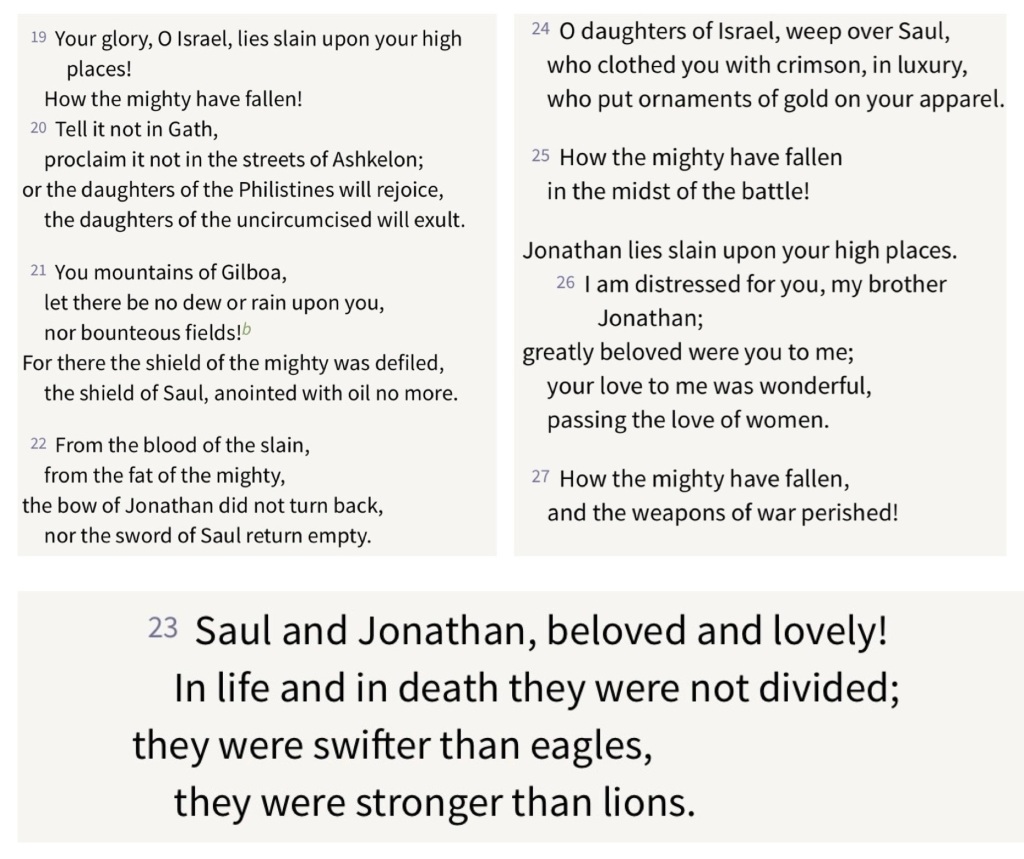

The poem in this week’s reading (2 Sam 1:19–27) offers a clear and loving acknowledgement by David of his respect and love for Saul. Despite the many difficulties encountered in their relationship, at the end of Saul’s life, David is able to acknowledge the virtue of the first King of Israel, and his son. “Saul and Jonathan, beloved and lovely!”, he sings; “in life and in death they were not divided; they were swifter than eagles, they were stronger than lions” (2 Sam 1:23).

Writing in With Love to the World, Kyounghee Cho reflects on the character of David seen in this passage. She writes, “David means “beloved”. David was tremendously loved by God. He was loved by the people of Israel, and now he is cherished and praised as an exemplary figure of faith by Christians worldwide. Today’s passage shows why God loved him and gives a lesson for believers of God. King Saul, David’s enemy, who had been chasing him for 10 years to kill him, died. While Saul’s demise might have been welcome news to David, he understood it not from his personal standpoint but from the perspective of the nation and its people.”

Kyounghee continues, “David paid tribute to Saul as the chosen leader of God and his soldiers as the army of the Lord of Hosts. He composed an elegy and instructed the people of Judah to learn it and sing it.” The song is a wonderful testimony to the king whose name came to characterise most strongly the chosen people, in covenant with the Lord God.

The story of David dominates the quasi-historical narrative of the early decades of the monarchy in Israel, stretching from his initial appearance at 1 Samuel 16 to his death at 1 Kings 2. The covenant people who come in following centuries are regularly identified as “the house of David” (2 Sam 3:1–6; 1 Ki 12:19–20, 26; 13:2; 14:8; 2 Ki 17:21; 2 Chron 10:19; 21:7; Neh 12:37; Ps 122:5; Isa 7:2, 13; 22:22; Jer 21:12; Zech 12:7–14; 13:1; Tobit 1:4; Sirach 48:15; 51:12; and see Luke 1:27).

This identification, of course, is highlighted many times in the New Testament, where Jesus is identified as “Son of David” in the Synoptic Gospels (Mark 10:47–48; 12:35; Luke 3:31; 18:38–39; and especially in Matt 1:1, 20; 9:27; 12:23; 15:22; 20:30–31; 21:9, 15; 22:42). This claim is also noted at John 7:42; Rom 1:3; 2 Tim 2:8; Rev 3:7; 5:5; 22:16). The heritage of David lives on in these stories.

The lament sung by David in 2 Sam 1 also provides a beautiful acknowledgement of the depth and strength of the love that undergirds this covenant between Jonathan and David. Peppering his song with the refrain “how the mighty have fallen” (vv. 19, 25, 27), David laments over his friend: “greatly beloved were you to me; your love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women” (2 Sam 1:26).

Could it be that, even in ancient Israel, such love between two men was valued and accepted? That will form the focus of the next blog that I will offer on this passage.

As we continue through narrative passages from the Hebrew Scriptures, this Sunday, we come to David’s poetic lament for his friend, Jonathan (2 Sam 1). This passage invites us to consider the depth of love that David expressed for Jonathan: “your love to me was wonderful, passing the love of women”. Just what can we make of this relationship? (This is the second of three posts this week on this topic.)

See

*****

With Love to the World is a daily Bible reading resource, written and produced within the Uniting Church in Australia, following the Revised Common Lectionary. It offers Sunday worshippers the opportunity to prepare for hearing passages of scripture in the week leading to that day of worship. It seeks to foster “an informed faith” amongst the people of God.

You can subscribe on your phone or iPad via an App, for a subscription of $28 per year. Search for With Love to the World on the App Store, or UCA—With Love to the World on Google Play. For the hard copy resource, for just $28 for a year’s subscription, email Trevor at wlwuca@bigpond.com or phone +61 (2) 9747-1369.