This week we once more read and hear the beginning of the story that Mark tells, about the very early stages of the public activity of Jesus. We have already read about John the baptiser during Advent (Advent 2), and heard Mark’s account of the baptism of Jesus (Epiphany 1).

Now, in this week’s Gospel reading (Lent 1), Jesus is baptised, plunged deep into the water, from which he emerges changed (1:9–11), driven into the wilderness, with wild beasts and angels, to be tested (1:12–13), and then announces what his message and mission will be (1:15–15).

This baptism is sometimes regarded as Jesus attesting to a deeply personal religious experience that he had in his encounter with John, who had been preaching his message of repentance with some vigour (1:4-11). His encounter with John deepens his faith and sharpens his commitment.

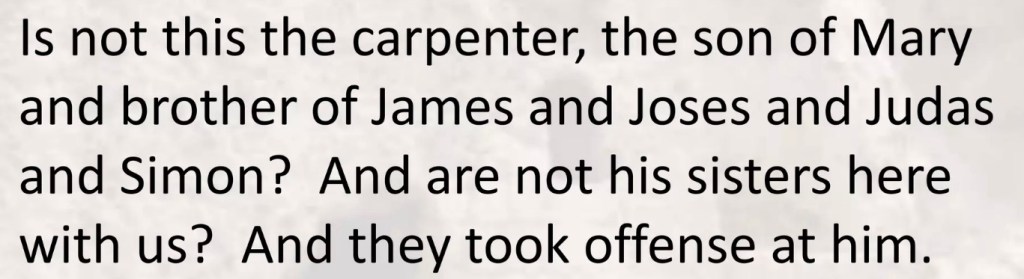

The relationship between Jesus and John is interesting. In the orderly account of things being fulfilled, which we attribute to Luke, it is clear from the start that John is related to Jesus (Luke 1:36). By tradition, they are considered to be cousins–although the biblical text does not anywhere expressly state this.

It seems also that some of the early followers of Jesus had previously been followers of John himself. This is evidenced in the book of signs, which we attribute to the evangelist John. Andrew, later to be listed among the earliest group of followers of Jesus, appears initially as one of two followers of John (John 1:35-40). They express interest in what John is teaching (John 1:39).

Andrew is the brother of Simon Peter, later acknowledged as the leader of the disciples of Jesus. He tells his brother about Jesus. It is Peter who comes to a clear and definitive understanding of the significance of Jesus, even at this very early stage: “we have found the Messiah” (John 1:41). Andrew and John are thenceforth committed disciples of Jesus.

Was Jesus engaging in “sheep-stealing”? Certainly, the dynamic in the narrative is of a movement shifting away from John the baptiser towards Jesus the Messiah; the juxtaposition of these two religious figures can be seen at a number of points (John 1:20, 29-34, 35-36; see also 3:22-30).

See further thoughts on John the baptiser in John’s Gospel at

and

(And I am looking forward to reading more about John in the most recent book by James McGrath, Christmaker: a life of John the Baptist, published by Eerdmans.)

None of this story relating to John is in view in the account we read in this Sunday’s Gospel. The rapid-fire movement in this opening chapter simply takes us from John, baptising in the Jordan, to Jesus at the Jordan and then in the wilderness, and on into Galilee, beside the lake and in Capernaum (Mark 1:1–45).

See my comments on the character of Mark 1 at

Mark has no concern with exploring the relationship between Jesus and John. He wishes only to indicate that, at the critical moment of the beginning of the public activity of Jesus, it was through contact with John, his message and his actions, that Jesus was impelled into his mission.

The Gospel account moves quickly on from the baptism, to a very different scene, set in the wilderness, where Jesus is tested, challenged about his call (1:12-15). The wilderness was the location of testing for Israel (Exod 17:1-7; Num 11:1-15; Deut 8:2). By the same token, the wilderness was also the place where “Israel tested God” (Num 14:20-23), when Israel grumbled and complained to God (see Exod 14-17, Num 11 and 14). Wilderness and testing go hand-in-hand.

The reference to Jesus being “forty days” in the wilderness evokes both the “forty years” of wilderness wandering for the people of Israel (Exod 16:35; Deut 2:7, 8:2, 29:5; Neh 9:21; Amos 2:10, 5:25), as well as the “forty days” that Moses spent fasting on Mount Sinai (Exod 34:28; Deut 9:9-11,18,25; 10:10).

Forty, however, should be regarded not as a strict chronological accounting, but as an expression indicating “an extended period of time”, whether that be in days or in years. It points to the symbolic nature of the account.

We see this usage of forty, for instance, in the comment in Judges, that “the land had rest forty years” (Judges 5:31, 8:28)–a statement that really means “for quite a long time”. Likewise, Israel was “given into the hands of the Philistines forty years” (Judges 13:1) and Eli the priest served for 40 years (1 Sam 4:18).

David the king reigned for 40 years (2 Sam 5:4, 1 Kings 2:11; 1 Chron 29:27), his son Solomon then reigned for another 40 years (1 Kings 11:42; 2 Chron 9:30), as also did Jehoash (2 Kings 12:1) and his son Jeroboam (2 Kings 14:23). If we take these as precise chronological periods, it is all very neat and tidy and orderly–and rather unbelievable!

Other instances of forty point to the same generalised sense of an extended time. Elijah journeyed from Mount Carmel to Mount Horeb “forty days and forty nights” (1 Kings 19:8), whilst the prophet Ezekiel’s announcement of punishments lasting forty years (Ezekiel 29:10-13) is intended to indicate “for a long time”, not for a precise chronological period. Jonah’s prophecy that there will be forty days until Nineveh is overthrown (Jonah 3:4) has the same force.

So the story of the testing of Jesus for “forty days in the wilderness” is not a precise accounting of exact days, but draws on a scriptural symbol for an extended, challenging period of time.

Details about the conversation that took place whilst Jesus was being tested in the wilderness are provided in the accounts in the Gospels attributed to Matthew (4:1-11) and Luke (4:1-13). This is not the case in Mark, where the much shorter account (1:12-13) focusses attention on the key elements of this experience: the wilderness, testing, wild beasts, angels–and the activity of the Spirit.

For more on Jesus in the wilderness, see

and

The Markan account of this period of testing is typically concise and focussed. The constituent elements in the story continue the symbolic character of the narrative.

The note that “he was with the wild beasts” sounds like the wilderness experience was a rugged time of conflict and tension for Jesus. However, commentators note that the particular Greek construction employed here is found elsewhere in this Gospel to describe companionship and friendly association: Jesus appointed twelve apostles “to be with him” (3:14); the disciples “took him [Jesus] with them onto the boat” (4:36); the man previously possessed by demons begged Jesus “that he might be with him” (5:14); and a servant girl declares to Peter that she saw “you also were with Jesus” (14:67).

If this Greek construction bears any weight, then it is pointing to the companionable, friendly association of the wild beasts with Jesus—a prefiguring of the eschatological harmony envisaged at the end of time, when animals and humans all live in harmony (Isaiah 11:6-9; Hosea 2:18). The wilderness scene has a symbolic resonance, then, with this vision.

Alongside the wild beasts, angels are present—and their function is quite specifically identified as “waiting on him” (1:13). The Greek word used here is most certainly significant. The word diakonein has the basic level of “waiting at table”, but in Markan usage it is connected with service, as we see in the descriptions of Peter’s healed mother-in-law (1:31), the women who followed Jesus as disciples from Galilee to the cross (15:41), and most clearly in the saying of Jesus that he came “not to be served, but to serve” (10:45). The service of the angels symbolises the ultimate role that Jesus will undertake.

Finally, we note that the whole scene of the testing of Jesus takes place under the impetus of the Spirit, which “drove him out into the wilderness” (1:12). This was the place that Jesus just had to be; the action of the Spirit, so soon after descending on him like a dove (1:11), reinforces the importance and essential nature of the testing that was to take place in the wilderness.

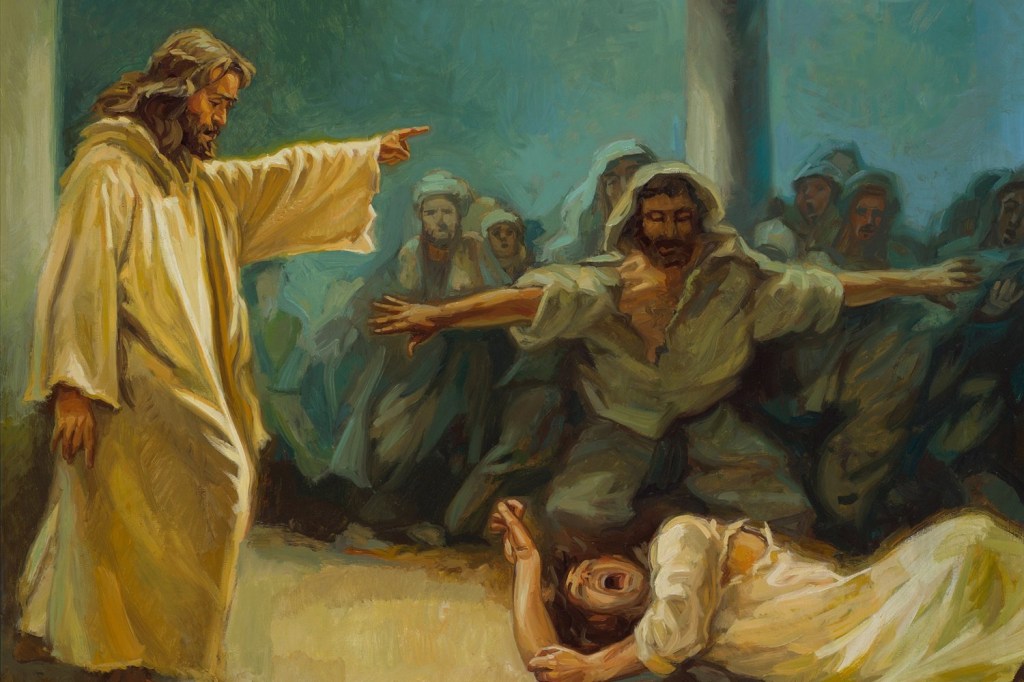

And the action of “driving out” is expressed in a word, ekballō, which contains strong elements of force—the word is used to describe the confrontational moment of exorcism (1:34, 39; 3:15, 22-23; 6:13; 9:18, 28, 38). The testing in the wilderness becomes a moment when Jesus comes face to face with his adversary, Satan—and casts his power aside. The more developed dialogues in Matthew and Luke expand on this understanding of the encounter.

Both of the key elements in this reading (baptism and testing) serve a key theological purpose in Mark’s narrative. They shape Jesus for what lies ahead. They signal that Jesus was dramatically commissioned by God, then rigorously equipped for the task he was then to undertake amongst his people. The two elements open the door to the activities of Jesus that follow in the ensuing 13 chapters, right up to the time when the long-planned plot against Jesus, initiated at 3:6, is put into action (14:1-2).

Of course, this story is offered in the lectionary each year on the first Sunday in the season of Lent. It serves as an introduction to the whole season. Jesus being tested in the wilderness points forward, to the series of events taking place in Jerusalem, that culminate in his crucifixion, death, and burial.

The narrative arc of Mark’s Gospel runs from the baptism and wilderness testing, through to death at Golgotha and burial in a tomb. The weekly pattern of Gospel readings during Lent follows a parallel path, from the wilderness testing of Lent 1, to the entry into Jerusalem on Lent 6, the farewell meal on Maundy Thursday, and the death and burial on Good Friday.

That is the path that Jesus trod. That is the way that he calls us to walk.