Scripture contains many sayings. Of particular note in the Hebrew Scriptures are “sayings of the wise” (Prov 24:23), offering insights into the best ways of living with integrity in daily life. The book of Proverbs refers to “thirty sayings of admonition and knowledge” (Prov 22:20), but in fact it contains a multitude of succinct two-part sayings, known as proverbs, attributed to King Solomon (Prov 10:1—29:27), Agur Ben Jakeh, a sage of Arabic descent (Prov 30:1–33), and King Lemuel, perhaps of Assyria (Masa) (Prov 31:1–9).

The Preacher, characteristically, bemoans that “the sayings of the wise are like goads, and like nails firmly fixed are the collected sayings that are given by one shepherd” (Eccl 12:11). He notes that “of the making many books there is no end, and much study is a weariness of the flesh” (Eccl 12:12). He presumably sees little need for saying after saying after saying.

Nevertheless, scripture as a whole has collected and retained “treasuries of wisdom” in which there are many “sayings of the wise” (Sir 1:25), sayings which are “life to those who find them, and healing to all their flesh” (Prov 4:22). Attention to these words means that “you may hold on to prudence, and your lips may guard knowledge” (Prov 5:2).

Faithful people are advised to “keep your father’s commandment, and do not forsake your mother’s teaching; them upon your heart always; tie them around your neck” (Prov 6:20)—words which evoke the directions given to Israel concerning the Torah itself: “bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as an emblem on your forehead, and write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates” (Deut 6:8–9).

So the “sayings of the wise” are regularly described in some of the terms used to describe Torah: they are “commandments” (Prov 2:1; 3:1; 4:4; 7:1–2; 10:8) and “precepts” (Prov 4:2), and like the Torah itself, they provide “instruction” (Prov 1:8; 4:1, 13; 8:10, 33; 9:9; 10:17; 15:5, 32–33; 19:20, 27; 23:12, 23; 24:32). Ben Sirach links the two when he advises, “if you desire wisdom, keep the commandments, and the Lord will lavish her [i.e. Wisdom] upon you”, for “the fear of the Lord is wisdom and discipline” (Sir 1:26–27).

The people are told that, “if you accept my words and treasure up my commandments within you, making your ear attentive to wisdom and inclining your heart to understanding … then you will understand the fear of the Lord and find the knowledge of God” (Prov 2:1–2, 5). The connection between “the fear of the Lord” and the wisdom that is conveyed by “the sayings of the wise” is manifest (Prov 1:7; 2:5; 9:10; 14:27; 15:33).

Penetrating into the wisdom contained within these sayings ought to come readily to those who are regular and persistent in listening to them; yet, as Job laments regarding God, “how small a whisper do we hear of him!”, and “the thunder of his power who can understand?” (Job 26:14). At the end of the long whirlwind speech of God, Job concedes that his knowledge of God had been quite inadequate, noting that “I had heard of you by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees you” (Job 42:5).

The introduction to the book of Proverbs recognises the difficulty of gaining clear understanding of these sayings, indicating that it takes work: “let the wise also hear and gain in learning, and the discerning acquire skill, to understand a proverb and a figure, the words of the wise and their riddles” (Prov 1:5–6).

Ben Sirach notes that “the one who devotes himself to the study of the law of the Most High” is one who “seeks out the wisdom of all the ancients, and is concerned with prophecies; he preserves the sayings of the famous and penetrates the subtleties of parables; he seeks out the hidden meanings of proverbs and is at home with the obscurities of parables” (Sir 39:1–3).

Those hidden meanings and obscurities may well be what has driven the psalmist, in the psalm offered in this coming Sunday”s lectionary psalm, to refer to “hidden things, things from of old” (Ps 78:2, NIV)—or more ominously, as the NRSV translates it, “dark sayings from of old” (Ps 78:2, NRSV). What are these hidden things, these dark sayings, from the past?

Although the psalmist refers to “the glorious deeds of the Lord, and his might, and the wonders that he has done” in years past, recounting them with admiration and gratitude (Ps 78:5–16), they note with pathos that the people “did not keep God’s covenant … refused to walk according to his law … forgot what he had done”, that they “sinned still more against him, rebelling against the Most High in the desert … tested God in their heart … spoke against God” (Ps 78:10–11, 17–19). Understanding came hard to the people.

The psalmist places these “hidden things”, these “dark sayings from of old” in parallel with parables (Ps 78:2). The Hebrew word translated as parable is mashal, which signals a comparison; it literally means “is like”. We know about parables from the use that Jesus made of them in his teaching. “The kingdom of heaven is like …”, or “what shall I compare the kingdom of God to?” are introductions to short stories which Jesus tells, in which the realm of God is explained with reference to a familiar situation in daily life—making bread, keeping sheep, tending a vineyard, seeking work, attending a marriage.

A mashal, a parable, is simply a comparison. So in Proverbs, we can read various parables: “the path of the righteous is like the morning sun, shining ever brighter till the full light of day; but the way of the wicked is like deep darkness; they do not know what makes them stumble” (Prov 4:18–19); “like a gold ring in a pig’s snout is a beautiful woman who shows no discretion” (Prov 11:22); “the words of the reckless pierce like swords, but the tongue of the wise brings healing” (Prov 12:18); “a king’s rage is like the roar of a lion, but his favour is like dew on the grass” (Prov 19:12); “like a roaring lion or a charging bear is a wicked ruler over a poor people” (Prov 28:15); and so on.

Elsewhere in the Hebrew Scriptures, we find comparisons—parables—that are short and succinct. A classic short, simple Another example is the proverb quoted by two prophets, about the impact of the Exile: “the parents have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge” (Jer 31:29; Ezek 18:2). The point of this saying is clear, and telling.

We also find more extended comparisons—parables with developed plots and allegorical elements. (In an allegory, particular individual features can play an independently figurative role, so that the story told becomes a kind of riddle which invites a response from the listener. “What do you think?” becomes the implied way that the allegory-riddle ends.) The most famous examples in the Hebrew Bible are Samuel’s story-parable comparing David with a callous rich herdsman in 2 Samuel 12 and the prophet’s lovesong-parable comparing Israel with an unfruitful vineyard in Isaiah 5.

The Hebrew word in parallel to mashal (משל, “parable”) in Ps 78:2, which is translated as “hidden things” (NIV) or “dark sayings” (NRSV), is the word chidah, חַידָה, which is most often translated as “riddle”. This word refers to a parable “whose point is deliberately obscured so that greater perception is needed to interpret it”, according to the Jewish Virtual Library (reference below). A good example is the riddle is that spoken by Samson, “out of the eater came something to eat; out of the strong came something sweet” (Judg 14:14). The narrative comment that follows is delightful: “for three days they could not explain the riddle”!

A number of proverbs are classified as riddles, especially in the section of Proverbs containing “the sayings of Agur son of Jakeh—an inspired utterance” (Prov 30:1). For instance: “There are three things that are never satisfied, four that never say, ‘Enough!’: the grave, the barren womb, land, which is never satisfied with water, and fire, which never says, ‘Enough!’” (Prov 30:15b—16). Another example comes a few verses later: ““There are three things that are too amazing for me, four that I do not understand: the way of an eagle in the sky, the way of a snake on a rock, the way of a ship on the high seas, and the way of a man with a young woman” (Prov 30:18–19).

In Psalm 78, we do not seem to have specific verses that can be categorised as riddles—rather, it presents as one of the psalms which retell the saga of the origins of Israel (as well as this psalm, see also Psalms 105, 106, 135 and 136). The particular perspective of the psalmist in retelling this story in Psalm 78 is that the people “should set their hope in God, and not forget the works of God, but keep his commandments” (v.7), in the hope that “they should not be like their ancestors, a stubborn and rebellious generation, a generation whose heart was not steadfast, whose spirit was not faithful to God” (v.8). After all, God had performed many miracles in the Exodus, at the formational stage of the people of Israel (vv.12–16).

Nevertheless, the repeated sinfulness shown by Israel in the wilderness (vv.17–19) is replicated in later times; in spite of all that God did for them in the wilderness (vv.20, 23–29), “they still sinned; they did not believe in his wonders” (v.32), “their heart was not steadfast toward him; they were not true to his covenant” (v.37), “they tested God again and again, and provoked the Holy One of Israel” (v.41), thereby incurring the great wrath of God (vv.44–51).

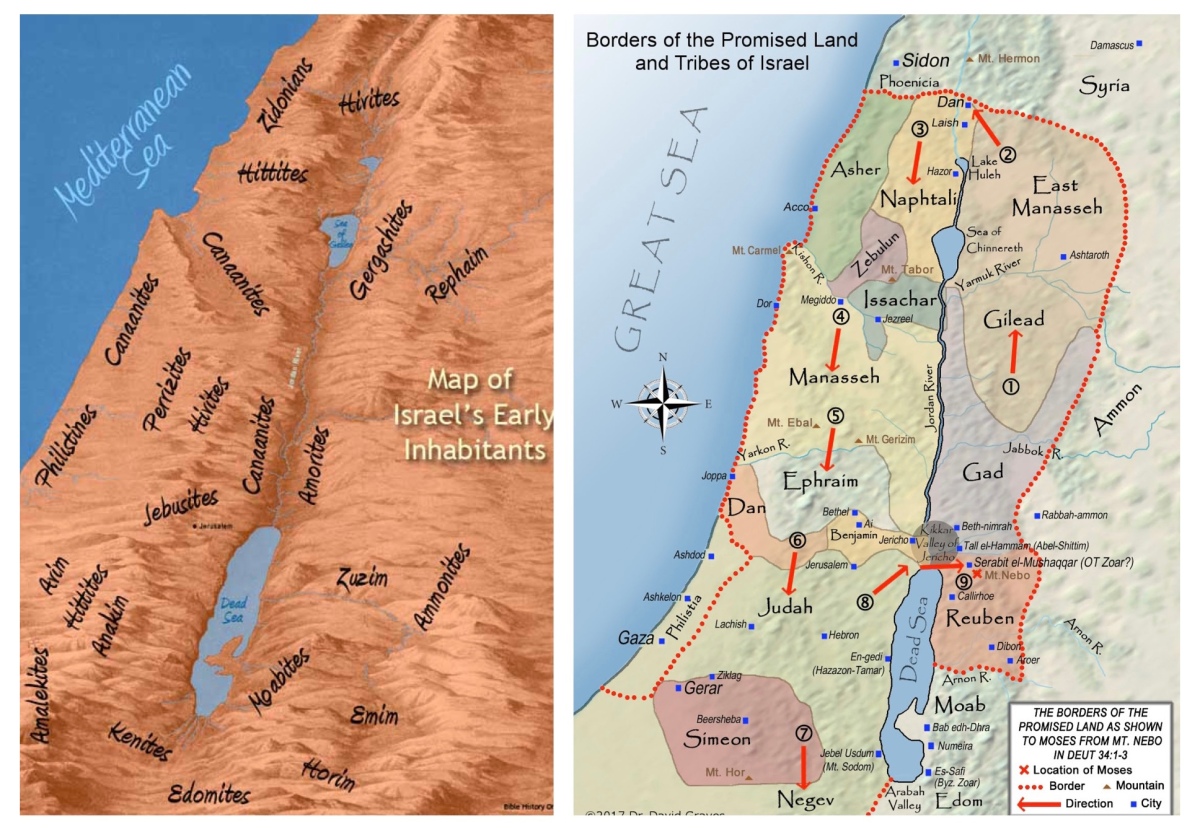

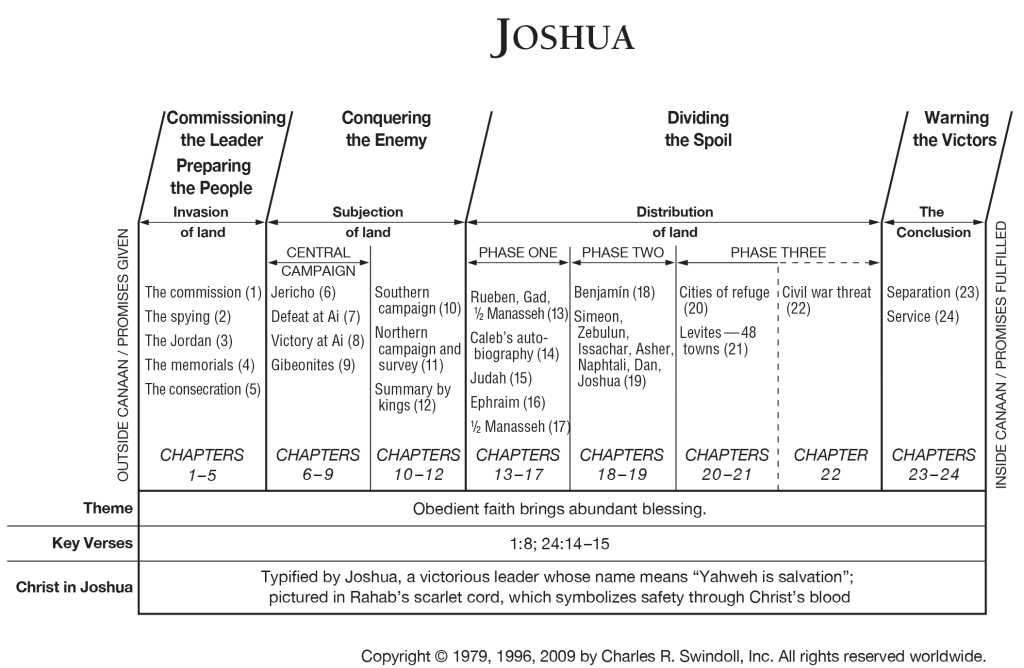

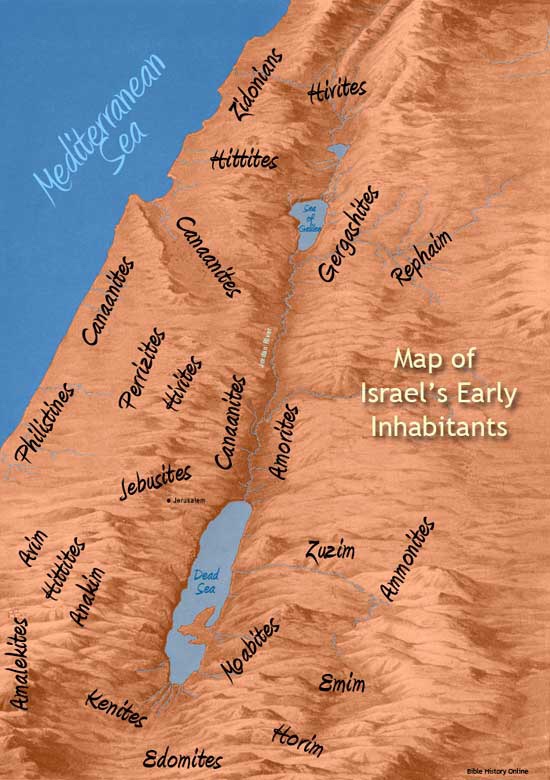

Even when God led them to Canaan and “drove out nations before them; he apportioned them for a possession and settled the tribes of Israel in their tents” (v.56), still “they tested the Most High God and rebelled against him; they did not observe his decrees, but turned away and were faithless like their ancestors; they twisted like a treacherous bow” (vv.56–57), incurring still more punishment (vv.58–64).

The psalm ends with a picture of pastoral bliss as God favoured the tribe of Judah with the site of the temple, and David is installed as the shepherd-king of the people (vv.65–72). The conclusion is encouraging; “David shepherded them with integrity of heart; with skillful hands he led them” (v.72).

Perhaps, notwithstanding this irenic ending, this is the chidah, the riddle, the dark saying of the past? Perhaps it is about the stubborn, incorrigible nature of human beings—exemplified by Israel’s regular return to sinful ways?

Perhaps the psalm was written in the knowledge of the persistent inadequacies and sinfulness of the kings who came after David? (We might note the regular refrain about the kings who “did evil in the eyes of the Lord” throughout the narrative books, first applied to Solomon at 1 Ki 11:6 and then forming a recurring formula of condemnation of many of the kings that followed him in the northern kingdom as well as a number in the southern kingdom).

Perhaps it is that, no matter how much God did for God’s people, their persistent sinfulness would always rise to the surface? If that is so, it is a dark saying, indeed.

On parables in Hebrew Scripture, see https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/parable

On later developments on rabbinic literature, see https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/11898-parable