Two weeks ago, we considered the section of Paul’s letter to the Romans which the lectionary offered: Paul grappling within “the sin that lives within me” (Rom 7:14–25a). The following week, the lectionary continued following the argument developed by Paul, as he rejoices that “there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (8:1–11). This week, we read the next passage in this letter, which reflects on “being led by the Spirit” and praying the prayer, “Abba, Father” (8:12–25).

In earlier weeks, we have been tracing the progression of Paul’s argument in this letter, as he sets out how he understudy the Gospel is “the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek” (1:16). He has set out the way that “the righteousness of God is revealed, through faith for faith” (1:17), the way that “this righteousness of God has been disclosed, and is attested by the law and the prophets” (3:21).

He has noted that this has been effected through “the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith” (3:24–25), and that this is consistent with the way that God had already acted, when “faith was reckoned to Abraham as righteousness” (4:9). This means, says Paul, that this same righteousness “will be reckoned to us who believe in him who raised Jesus our Lord from the dead” (4:24).

Accordingly, Paul tells the Romans that, “since we are justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have obtained access to this grace in which we stand; and we boast in our hope of sharing the glory of God” (5:1–2). What follows is a detailed exploration of what this theologically rich affirmation entails: understanding the significance of the death of Jesus for believers (5:6–11); exploring the origin of sin and the parallel offering of being declared to be righteous (5:12–21); the life of faith with the risen Christ (6:1–11); the relationship between sin and grace (6:12–23); the place of sin, the law, and death in the life of faith (7:1–25); and life in the Spirit (8:1–11).

This is heavy going: Paul is entering into difficult areas for consideration—but he plunges in head-first, deploying the familiar techniques he has used in some of his earlier letters: vigorous debate using the techniques of diatribe, question-and-answer dialogues, with scriptural citation and exposition in the style of the rabbis (see especially Galatians and both letters to the Corinthians). This shows the complex, cross-cultural nature of Paul’s life, and the sophisticated way that he operated.

In the section of this letter that is offered this coming Sunday, then (8:12–17), Paul pauses the vigorous debating style of earlier sections, and here operates more by offering pastoral exhortation in the manner of moral philosophers, as he does especially in 1 Thessalonians and Philippians. In this instance, the focus is to offer encouragement regarding the present state of believers, reiterated in these words: “all who are led by the Sprit of God are children of God” (8:14), “you have received a spirit of adoption” (8:15), “we are children of God” (8:16).

Paul continues his dualistic perspective, here, by contrasting “to love according to the flesh” with being “led by the Spirit of God”, which means to “put to death the deeds of the body” (8:13–14). This dualism, from the strong Greek influence on Paul (and, indeed, on many of his hellenised Jewish contemporaries) drives his thoughts away from the integrated Hebraic view of the whole person, the nephesh, which is at the heart of how the Hebrew Scriptures regard humanity.

Those scriptures had clearly indicated that God created nephesh hayah, “living creatures”, in the seas (Gen 1:20, 21) and on the earth (Gen 1:24); indeed, in “every beast of the earth … every bird of the air … everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life (nephesh hayah)” (Gen 1:30). The same phrase occurs in the second creation story, describing how God formed a man from the dust of the earth and breathed the breath of life into him, and “the man became a living being (nephesh hayah)” (Gen 2:7). The claim that each living creature is a nephesh is reiterated in the Holiness Code (Lev 11:10, 46; 17:11).

For Paul, however, flesh and spirit compete with one another within the same person; he has stated this conflict clearly at Rom 7:5–6, and developed his thinking further at 8:3–9. In an earlier letter, Paul has taken this flesh/spirit dichotomy as a primary lens for viewing the various conflicts and problems within the gatherings in Corinth (1 Cor 3:1–4; 6:16–17); a similar dynamic can be seen in the extended allegory of Sarah and Hagar (Gal 4:21–31; see esp. v.29). Concerning the dissension in Philippi, he is clear: “we who worship in the Spirit of God … have no confidence in the flesh” (Phil 3:3).

It is a shame that this adoption of Hellenistic dualism has overshadowed and then overwhelmed the rigorously wholistic approach to the human condition that is the gift of the Hebraic tradition. Paul’s words occupy much less space in our scriptures than do the material from the ancient scrolls of Israel, but we have allowed the writings of Paul (the seven authentic letters, as well as the later pseudonymous works) to take up so much more space than those earlier works—and, indeed, more space than the Gospels in the New Testament—in the thinking, writing, and doctrinal exposition of Christianity.

This dualistic dynamic that Paul has adopted and integrated into his way of thinking spills out into the further imagery that is used in Rom 8, where the flesh is entangled in “a spirit of slavery” which leads people to “fall back into fear”, but believers “have received a spirit of adoption” which attests that they are “children of God” (8:15–16).

That people can be considered to be “children of God” is a common point of view today; it is a way of recognising that we are all created by God and share the same characteristics as human beings. It is perhaps a point of view that has developed from the observation that Paul occasionally refers to “the children of God”.

He assures the Galatians that “in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith” (Gal 3:26), and encourages the Philippians to “do all things without murmuring and arguing, so that you may be blameless and innocent, children of God without blemish in the midst of a crooked and perverse generation, in which you shine like stars in the world” (Phil 2:14–15).

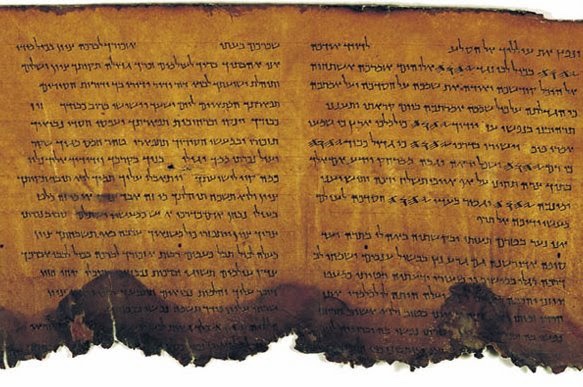

The term occurs five times in this immediate section of Romans (Rom 8:14, 16, 19, 21; 9:8), where Paul makes it clear that “all who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God” (8:14) and “it is not the children of the flesh who are the children of God, but the children of the promise are counted as descendants” (9:8). This usage is different from the contemporary sense that “we are all children of God because God has created us all”—for Paul, the children of God are birthed into that state by virtue of their faith, being led by the Spirit and finding themselves to be “in Christ”.

The phrase is used by the author of 1 John in a similar manner, comparing “the children of God and the children of the devil”—although in the rigorous view taken by this writer, the former “have been born of God [and] do not sin, because God’s seed abides in them” whilst the latter “do not do what is right [and] are not from God”, and indeed they “do not love their brothers and sisters” (1 John 3:9–10; see also 3:1; 5:2).

The phrase appears also in two sayings attributed to Jesus: a blessing of “the peacemakers” (Matt 5:9), and a discussion of those in “the age to come” who “cannot die anymore, because they are like angels and are children of God, being children of the resurrection” (Luke 20:36).

The phrase is also found in two narrative comments by the author of John’s Gospel, affirming that Jesus “gave power to become children of God” to “all who received him” (John 1:14), and in a summation of a high priestly prophecy that Jesus was “about to die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the dispersed children of God” (John 11:52). So this usage is diverse and generalised, rather than conveying a specific focus, which is what Paul clearly has in mind in Rom 8:12–25.

Those described as “children of God”, we have noted, are also described by Paul as having a “spirit of adoption”. This language appears as Paul encourages the Galatians, explaining the significance of Jesus in the short saying: “when the fullness of time had come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, in order to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as children” (Gal 4:4–5). He continues that, “because you are children, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Gal 4:6), the very same prayer that he references in Rom 8.

The concept of adoption is taken up in the language of a post-Pauline letter, which declares that God “destined us for adoption as his children through Jesus Christ, according to the good pleasure of his will, to the praise of his glorious grace that he freely bestowed on us in the Beloved” (Eph 1:5).

In his letter to the Romans, Paul equates this adoption with “the redemption of our bodies” (Rom 8:23), indicating that the concept fits neatly, in Paul’s thinking, within his adopted hellenistic dualistic worldview. The Spirit which gifts this adoption to believers as “children of God” is the Spirit which makes us to be “heirs, heirs of God and joint heirs with Christ” (8:17). The end result of this process is, as Paul then declares, that “we suffer with him [Christ] so that we may also be glorified with him” (8:17).

The idea that we are glorified with Christ is then reiterated later in this chapter, where Paul writes about the overarching providence of God, stating that “those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son”, using once again a family image to explain what this means: “in order that he might be the firstborn within a large family” (8:29). This process drives inexorably towards the moment of glorification: “those whom he predestined he also called; and those whom he called he also justified; and those whom he justified he also glorified” (8:30).

This is an unusual portrayal of what this means for believers. To “be glorified” in scriptural usage normally applies to God (Lev 10:3; 1 Chron 22:5; Isa 26:15; 44:23; 49:3; 60:21; 66:5; Sir 3:20; 38:6; 45:3; Mark 2:12; Matt 9:8; Luke 5:26; 7:16; John 12:28; 13:31–32; 14:13; 15:28; 17:4) or to Jesus (John 11:4; 12:16, 23; 13:31), although there are some late references to Israel being glorified (Isa 55:3–5), Moses being glorified (Sir 44:25–45:3), and then to David also being glorified (Sir 47:2–6). Paul is placing believers in Christ within that same stream of being glorified by their strong faith and good works.

As he writes to the Romans, Paul refers to a prayer that we find on the lips of Jesus: “Abba! Father!” (Rom 8:15; Mark 14:36). Jesus prays this way in the Garden of Gethsemane, when he was “distressed and agitated” (Mark 4:33) as he grapples with what he now knows is in store for him: “the hour has come; the Son of Man is betrayed into the hands of sinners” (Mark 14:41). It is a reflexive prayer, coming almost automatically from within the depths of Jesus’ inner life, in his very being that is “deeply grieved, even to death” (Mark 14:34).

Paul has also referenced this prayer in a similar moment of encouragement in his letter to the Galatians, when he reminds them that Jesus had come “in order to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as children” (4:4–5). It is because of this state, as children of God, that “God has sent the Spirit into our hearts, crying ‘Abba! Father!’” (Gal 6:6).

Quite tellingly, Paul notes that this is a prayer that we “cry” (Rom 8:15), using the Greek word, kradzein, which is used both in Gospel accounts of casting out demons (Mark 1:23), but, more significantly, 40 times in the LXX translation of Psalms (Ps 3:4; 4:3; 8:6; 22:2, 5; etc). It indicates an intensity of focus in what is being said.

The psalmist “cries aloud to the Lord” (Ps 3:4; 27:7; 77:1) and the response is clear, for the Lord “fulfils the desire of all who fear him [and] hears their cry and saves them” (Ps 145:19), “he gives to the animals their food, and to the young ravens when they cry” (Ps 147:9), and as “I waited patiently for the Lord, he inclined to me and heard my cry” (Ps 40:1).

The Abba Prayer has come to have a life all of its own in contemporary spirituality. It is offered in scripture, both as words that Jesus prayed, and as words which Paul offers to believers for our prayers. It is a good foundation to foster our relationship with God in prayer.

In the final section of the reading that the lectionary offers us for this coming Sunday, Paul makes much of the promise that, since believers are “children of God” and thus “joint-heirs with Christ”, so they will “be glorified with him” (8:17). This theme continues on in the consideration that Paul gives to “the glory about to be revealed to us” (8:18), when “the creation will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God” (8:21), and when “those whom he called he also justified”, such that “those whom he justified he also glorified” (8:30).

Earlier in this same chapter, Paul has reported to the Romans that “we boast in our hope of sharing the glory of God” (5:2). This boastful praise for the promised, soon-to-be realised glory, draws on a strong theme in Hebrew scripture. The glory of God is present in the stories that recount the formation of Israel, through the years in the wilderness (Exod 16:6–10; Num 14:22), on Mount Sinai (Exod 24:16–17; Deut 5:22–24), in the Tabernacle (Exod 40:34–35; Lev 9:23; Num 14:10; 16:19, 42; 20:16), and in the temple (1 Ki 8:1–11; 2 Chron 7:1–4).

The psalmists reinforce the notion that the glory resides in the sanctuary (Ps 26:8; 63:2; 102:16; Hag 2:3) and in the land of Israel (Ps 85:9). In some psalms the realm of God’s glory is extended to be “over the waters” (Ps 29:1–4), “over all the earth” (Ps 57:5; 72:19; 97:6; 102:15; 108:5; also Isa 6:3; 24:15–16; 60:1–2; Hab 2:14) and even to “the heavens” (Ps 19:1; 113:4; 148:13; and Hab 3:3).

This concept of God’s glory plays an important role in Paul’s argument in Romans. “All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God”, Paul brazenly declares (Rom 3:23); some who claim to know God “exchanged the glory of the immortal God for images resembling a mortal human being” (1:23), in contrast to “those who by patiently doing good seek for glory and honour”, to whom “glory and honour and peace” will be given (2:7, 10).

To Abraham, who “grew strong in his faith as he gave glory to God”, his faith would be “reckoned as righteousness” (4:20–22). In God’s time, “the freedom of the glory of the children of God” will given to the creation (8:21). Within the communities of faith in Rome, the imperative of “welcoming one another” is to be done “for the glory of God” (15:7). This glory is God’s gift to people of faith, and indeed to the whole creation. It is this which Paul here yearns for and anticipates with confident hope.

However, it is imperative that we notice that when Paul writes about being glorified with Christ, he prefaces that with an important condition—“if, in fact, we suffer with him” (8:17). Sharing fully in the fruits of God’s glory, as joint-heirs with Christ, means sharing completely in the suffering that Christ experienced, in his betrayal, arrest, trials, and crucifixion.

It is, as Paul famously writes to the Philippians, to “suffer the loss of all things, and regard them as rubbish” (Phil 3:8); and to the Galatians, that “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:19–20); and again, as he has written to the Romans, “we have been buried with Christ by baptism into his death, so that … we might walk in newness of life” (Rom 6:4), and accordingly, “you must consider yourselves dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus” (Rom 6:11).

There is no easy path to that much-anticipated glory; rather, it requires that we enter completely into the passion, the sufferings, of Christ. And that is the challenge that stands before us from these words of Paul.

Next week, the lectionary brings to a close the sequence of passages from chapter 5 through to chapter 8, moving inexorably to Paul’s rhetorical climax of great power: “If God is for us, who is against us? … Who will separate us from the love of Christ? … [nothing] will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” (8:31–39). It then thrusts us into chapters 9 to 11, where Paul sets out his complex arguments concerning Jews and Gentiles—which may, in fact, be the central purpose of the whole letter! (so, more blogs are coming …)