Jeremiah lived at a turning point in the history of Israel. The northern kingdom had been conquered by the Assyrians in 721 BCE; the elite classes were taken into exile, the land was repopulated with people from other nations (2 Kings 17). The southern kingdom had been invaded by the Assyrians in 701 BCE, but they were repelled (2 Kings 18:13–19:37). King Hezekiah made a pact with the Babylonians, but the prophet Isaiah warned that the nation would eventually fall to the Babylonians (2 Kings 20:12–19). Babylon conquered Assyria in 607 BCE and pressed hard to the south; the southern kingdom fell in 587 BCE (2 Kings 24–25) and “Judah went into exile out of its land” (2 Ki 25:21).

Jeremiah lived in the latter years of the southern kingdom, through into the time of exile—although personally, he was sent into exile in Egypt, even though most of his fellow Judahites were taken to Babylon. The difficult experiences of Jeremiah as a prophet colour many of his pronouncements. He is rightly known as a prophet of doom and gloom.

And yet, in the midst of his despair, Jeremiah sees hope: “the days are surely coming, says the Lord, when I will restore the fortunes of my people, Israel and Judah, says the Lord, and I will bring them back to the land that I gave to their ancestors and they shall take possession of it” (30:3).

He goes on to report that the Lord says to the people, “I will be the God of all the families of Israel, and they shall be my people”, for “the people who survived the sword found grace in the wilderness; when Israel sought for rest, the Lord appeared to him from far away” (31:1–2).

This grace was made known to the people in the affirmation that God makes, “I have loved you with an everlasting love; therefore I have continued my faithfulness to you” (31:3).

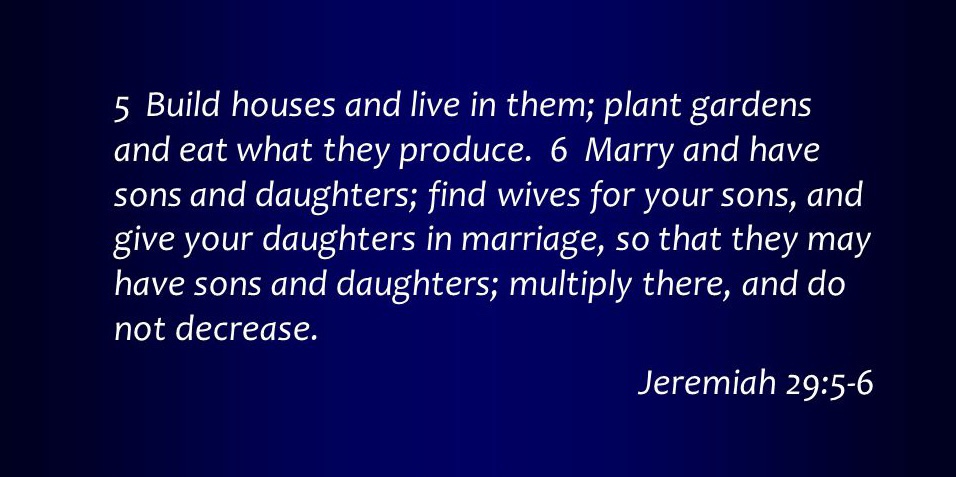

In this context, Jeremiah indicates that the Lord “will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah … I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (31:31–34). This covenant will give expression to the love and faithfulness of the Lord, which is how God’s grace is to be known by the people. This renewal of covenant is offered in grace; the requirements of the covenant make clear and tangible the grace-filled relationship that the people have with their God.

Clear appreciation for the grace that is offered to the people by the laws which guide the people to keep the covenant can be seen in the affirmation of the Torah as “perfect, reviving the soul … sure, making wise the simple … right, rejoicing the heart … clear enlightening the eyes … pure, enduring forever … true and righteous altogether … more to be desired than gold … sweeter also than honey” (Ps 19:7–14), and then by the majestically grand affirmations of Torah in the 176 verses which are artistically-arranged into acrostic stanzas of Psalm 119 (“happy are those … who walk in the way of the Lord … I long for your salvation, O Lord, and your law is my delight”, vv.1, 174). The laws shape the way that the covenant is kept; the covenant gives expression to the steadfast love and grace of God.

*****

The renewal of the covenant was not a new idea in the story of Israel. God had entered into covenants with Abraham, the father of the nation (Gen 15:1–21) and before that, in the story of Noah, with “you and your descendants after you, and with every living creature that is with you … that never again shall all flesh be cut off by the waters of the flood” (Gen 9:8–11). The covenant given to Moses on Mount Sinai (Exod 19:1–6), accompanied by the giving of the law (Exod 20:1–23:33), is sealed in a ceremony by “the blood of the covenant” (Exod 24:1–8).

The covenant with the people that Moses brokered is renewed after the infamous incident of the golden bull (Exod 34:10–28), then it is renewed again under Joshua at Gilgal, as the people enter the land of Canaan after their decades of wilderness wandering (Josh 4:1–24). It is renewed yet again in the time of King Josiah, after the discovery of “a book of the law” and his consultation with the prophet Huldah (2 Chron 34:29–33).

The covenant will be renewed yet another time, after the lifetime of Jeremiah, when the exiled people of Judah return to the land under Nehemiah, when Ezra read from “the book of the law” for a full day (Neh 7:73b—8:12) and the leaders of the people made “a firm commitment in writing … in a sealed document” which they signed (Neh 9:38–10:39). So renewing the covenant, recalling the people to their fundamental commitments made in relationship with God, is not an unknown process in the story of ancient Israel.

However, the particular expression of renewal that Jeremiah articulates is significance, not only for the exiled Israelites, but also centuries later, for the followers of the man from Nazareth who came to be recognised as God’s Messiah. Jeremiah’s articulation of the promise of a “new covenant” will prove to be critical for the way that later writers portray the covenant renewal undertaken by Jesus of Nazareth (1 Cor 11:25; Luke 22:20; 2 Cor 3:6–18; Heb 8:8–12).

Especially significant is the claim that this renewed covenant “will not be like the covenant that I made with their ancestors when I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt—a covenant that they broke” (Jer 31:32), for God “will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people” (31:33). It is a covenant which has “the forgiveness of sins” at its heart (31:34)— precisely what is said of the “new covenant” effected by Jesus (Matt 26:28; and see Acts 5:31; 10:43; 13:38; 26:18).

*****

To signal his confidence in this promised return, Jeremiah buys a field in his hometown of Anathoth from his cousin Hanamel (32:1–15). the purchase serves to provide assurance that the exiled people will indeed return to the land of Israel; “houses and fields and vineyards shall again be bought in this land” (32:15).

Jeremiah exhorts the people to “give thanks to the Lord of hosts, for the Lord is good, for his steadfast love endures forever!” (33:11). Here, Jeremiah makes use of a phrase that recurs in key places throughout Hebrew Scripture, where it crystallises what the Israelites appreciated about the nature of God. The Lord is said, a number of times, to be “gracious and merciful, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love” (Exod 34:6; 2 Chron 30:8–9; Neh 9:17, 32; Jonah 4:2; Joel 2:13; Ps 86:15; 103:8, 11; 111:4; 145:8–9). This is the Lord God who enters into covenant, time and time and again, with the people.

There is a strong sequence of affirming, hopeful oracles which characterise this section of Jeremiah, from “the days are surely coming … when I will restore the fortunes of my people, Israel and Judah, and I will bring them back to the land that I gave to their ancestors” (30:3) to “I will restore their fortunes, and will have mercy on them” (33:26). All of this is done because, as the Lord declares, “only if I had not established my covenant with day and night and the ordinances of heaven and earth, would I reject the offspring of Jacob and of my servant David” (33:25–26). It is the covenant which holds the Lord and the people together.

So Jeremiah offers a clear sign of hope for the future; in the places laid waste by the Babylonians, “in all its towns there shall again be pasture for shepherds resting their flocks … flocks shall again pass under the hands of the one who counts them, says the Lord” (33:12–13). As the people return to the land, the Lord “will cause a righteous Branch to spring up for David; and he shall execute justice and righteousness in the land” (33:15).

This oracle, also, is significant for the later community that developed from the followers of the man from Nazareth; the promise of a “righteous branch for David” becomes the title “Son of David”, which is then applied to Jesus in all three Synoptic Gospels (Mark 10:47–48; 12:35; Matt 1:1, 20; 9:27; 12:23; 15:22; 20:30, 31; 21:9, 15; 22:42; Luke 18:38–39). The whole sequence of oracles in this section of Jeremiah is of key significance for followers of Jesus in later ages.