Respectable gentlemen, pillars of society, and good citizens all. Advocating obedience and emphasising responsibility. Preaching “good news” which requires trust, faith, and “a serving heart”. Teaching “godliness” which entails decency, seemliness, and propriety. The outward appearance looks good, honourable, and worthy.

What this wraps around, however, is a world of rigorous discipline and strong patriarchy, a relentless drive to ensure submission to “the head” (i.e. the man) and obedience to parents, a persistent marginalising and oppressing of women, a strident denunciation of all who stray from the “narrow way” of “Bible-believing Christianity”, and an incessant repetition of the fundamental message that “all have sinned” and all such sinners can only be “saved by the blood of the lamb”. Obedience and disciplined acceptance of what authority decrees are essential.

This is the world of hard-line conservative evangelicalism, which has long been part of the Establishment in Britain and, with a strong Puritan twist, has captured so many Protestant churches in the USA. It is present in Australia, most strikingly in the Sydney Anglican diocese, but there are tentacles into many other Anglican dioceses around the country—and, indeed, into a number of other denominations as well. (There has been a small and declining element of this in my own denomination; the most vigorous proponents of this distorted theology wisely decided to leave a couple of years ago.)

We have seen the very worst manifestation of British conservative evangelical Christianity in recent times, with revelations relating to the masochistic treatment meted out to school-age boys over many years by the head of a reputable evangelical organisation, the Iwerne Trust. The Trust held annual camps to instruct schoolage boys in so-called “muscular Christianity”. These camps were run on military lines; the leader of the camp was the “commandant”, his deputy was the “adjutant”, and all of the leaders were known as “officers”. (It sounds just like the regimented school cadets system that I remember from my schooldays, decades ago.)

It was in this kind of environment that a barrister named John Smyth found an opportunity to implement his harsh disciplininary measures. Smyth was camp leader on the Iwerne camps 1964–84, chair of the Iwerne Trust 1974–81, and a Scripture Union trustee 1971–79. (The Iwerne Trust operated under the umbrella of Scripture Union, but appears to have been only loosely associated with SU leadership.)

The details of what he did have been documented in church reports—the first, written around 40 years ago, but I comprehensively shelved by those in the know—as well as in media interviews with survivors and even his own son, who endured emotional abuse and vicious physical violence at the hands of his father (aided and abetted by his compliant mother). What is revealed is truly, deeply disturbing.

Smyth died some years ago. He had been forced to relocate countries twice in his life, fleeing the revelations of his horrid modus operandi. But each time he moved on without any brief of the suspicions relating to him being forwarded to the next “Christian” organisation that he worked with. He avoided justice throughout his lifetime.

The latest public push regarding this man and the way his actions were covered up by complicit colleagues has led to the very public resignation of the Archbishop of Canterbury, who knew Smyth decades ago, apparently knew the suspicions swirling around him then, clearly learnt the full truth over a decade ago, but never did anything to bring this person to account. Welby has become the scapegoat for widespread institutional failure.

What a shocking indictment! Welby’s sins, whilst totally unacceptable, seem to pale in comparison to the atrocious coverups of so many male clergy. It is just disgusting. But of course we know that the general culture fostered by hardline conservative evangelicals is punitive, oppressive, homophobic, and completely alien to the Gospel. Smyth was living out a distorted theology that had been developed from the increasingly strident message that was being promulgated by hardline evangelicals within the church—and which still lives and grows today. And he got away with it because so many people just gave him “another chance”, or turned a blind eye, wanting to protect the reputation of the church, or simply refused to believe that such a “devout man” could do this.

Prof. Adrian Thatcher has written with his typical clarity on this matter, arguing that “the Church of England will never ‘learn lessons’ about the causes of Smyth’s shocking exploits until it reviews its own theological failings.” In particular, he maintains that “many of [the Church of England’s] members and organisations do hold ideological beliefs that hurt people and are ‘followed at the expense of a core care and regard for every human being’.” He notes that there are “copious references among the testimony of survivors in the [2024 Makin] Report to misogyny, homophobia, to ‘muscular Christianity’, to outrageous sexism (remember the ‘lady helpers’), in the camps and organisations where Smyth’s wickedness was propagated.”

Thatcher quotes Makin’s conclusion that “the patriarchal approach in the organisations and cultures that John Smyth operated, was a conducive and organisational factor to the abuse”. That patriarchal approach is a key characteristic of conservative evangelicalism, whose leaders, Thatcher argues, are still “protected from an overdue examination of their patriarchal, sexist and homophobic beliefs, all ‘Bible-based’, and the harm that derives from them.”

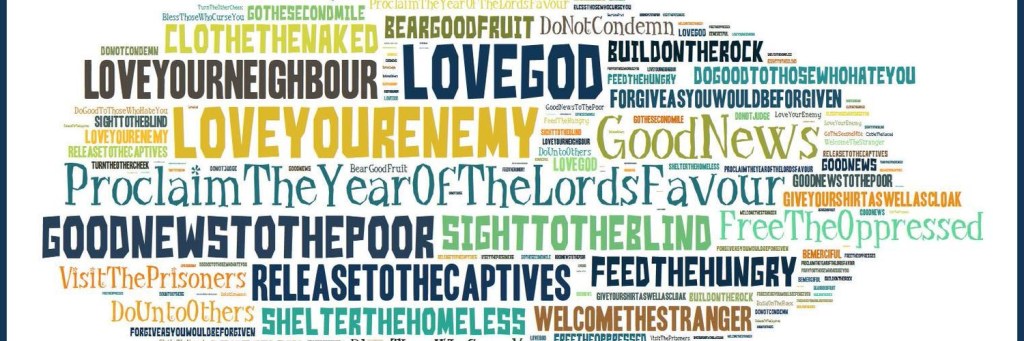

The challenge to hardline conservative evangelical leaders is to reflect on the harm done by their ideological attachment to this distorted theology, to repent of the sins that have been and are being committed, and to rediscover the actual Gospel—good news—for humanity, which, as the latest Church of England media release says, is not about “a seemingly privileged group from an elite background to decide that the needs of victims should be set aside, and that Smyth’s abuse should not therefore be brought to light”, but rather “about proclaiming Good News to the poor and healing the broken hearted.”

Amen.

The Church of England’s media release about the Makin Review is at https://www.churchofengland.org/media/press-releases/independent-review-churchs-handling-smyth-case-published

Prof. Adrian Thatcher’s analysis is at

One detailed discussion of the complicity of some in the terrible coverup that has occurred is at https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/ideas/religion/church-of-england/68541/justin-welby-is-a-scapegoat-for-establishment-failures?

Another is at https://sixtyguilders.org/2024/11/18/st-ebbes-and-the-smyth-scandal-an-inadequate-response/?