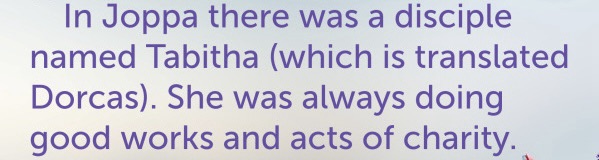

Tabitha (also known as Dorcas) is an unlikely role model for disciples. There is no record of her preaching the Gospel, or casting out demons; and no direct statement that she was hosting a house church or offering hospitality; although she did make clothing for widows and this could be seen as an act of hospitality, perhaps. Rather, Tabitha is known simply for the fact that she was a disciple who was “devoted to good works and acts of charity” (Acts 9:36, NRSVUE translation).

Quite strikingly, she is a woman who is named (a striking feature, as many women in scripture go unnamed); and we are given her name in two languages, Aramaic and Greek. It is possible that Tabitha is derived from Tsibiah, the name of the mother of King Jehoash (1 Ki 12:1). So Tabitha is worth remembering. Mostly, however, she is remembered for the fact she had fallen ill and had died; when Peter and two other disciples came to Joppa, where she lived, she was brought back to life (9:37, 40–41).

Whilst this may mean that Tabitha exemplified the pathway that Jesus trod (into death, then back to life), she is not put forward as an example of that paradigmatic pattern (which Paul, for instance, sees as fundamental; see 1 Cor 15:3–4; Rom 6:3–8, 11; 2 Cor 4:8–11; Gal 2:19–20; Phil 3:10–11). Why, then, is this story included in Acts? Tabitha is part of a group of stories that form a crucial pivot in the storyline of Acts, from the time of the church in Jerusalem (chs.1—7) to the activity amongst the Gentiles (chs.13 onwards) that begins to spread the good news “to the ends of the earth” (cf. Acts 1:8).

The way that Tabitha is introduced may well serve to point to her ultimate significance in this book which records various incidents because of their foundational importance for Christian faith and life. In the very first verse, Tabitha is praised for “doing good works” and performing “acts of charity”. This is reminiscent of the introductions offered for a number of other characters, all valued for their piety and the good things that they did (not just “what they believed”).

Good works and acts of charity

Elizabeth and Zechariah, at the start of Luke’s Gospel, are described as “righteous before God, living blamelessly according to all the commandments and regulations of the Lord” (Luke 1:6). They did what was considered to be good, performing the acts of charity required by Torah. Simeon is introduced as a man who was “righteous and devout” (Luke 2:25) whilst Anna “never left the temple but worshiped there with fasting and prayer night and day” (Luke 2:37). They too did what is good, as they adhered to Torah. And in Acts, immediately after the story of Tabitha, we meet Cornelius, “a devout man who feared God with all his household; he gave alms generously to the people and prayed constantly to God” (Acts 10:2). Cornelius is yet another example of someone who did good.

So Tabitha “was devoted to good works and acts of charity” (Acts 9:34). Often these terms are viewed through a narrow lens, based on a hardline reading of Paul’s affirmation that “a person is justified not by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ … we [are] justified by faith in Christ, and not by doing the works of the law, because no one will be justified by the works of the law” (Gal 3:26). He offers a similarly strenuous affirmation along these lines at Rom 3:24–25, 28–30, followed by his detailed argument that Abraham was justified by his faith, and not by any “works of the law” (such as circumcision; see Rom 4:1–25).

This Pauline focus on “faith, not works” generated a negative attitude towards “doing good”. This came to full fruition amongst the Reformers, when they rejected the medieval Roman Catholic system of indulgences (accruing merit in the eyes of God through the support of charitable works, amongst other things) and declared that “doing good” and “charitable works” were of a lesser value than “simply believing” and “having faith in Jesus”. From this perspective, amongst more recent Protestant churches, a healthy disdain for these good deeds has developed. Good works were not “the heart of the Gospel”. Tabitha would hardly be seen by them as a role model for a faithful disciple.

Doing good

Yet “doing good” and performing “charitable deeds” are valued as positive and advocated as necessary by many voices in scripture. Prophets instructed the people of Israel to “learn to do good, seek justice” (Isa 1:17; see also Isa 41:23; Jer 4:22), following the example of the Lord God who does good (Micah 2:7; Zech 8:15). Psalmists sang a refrain to “depart from evil, and do good” (Ps 34:14; 37:27) and to “trust in the Lord and do good” (Ps 37:3), once again following the example set by the Lord God, who is acknowledged in this manner: “you are good and you do good” (Ps 119:68).

Similar advice appears in later Jewish literature. In the story of Tobit, the angel Raphael in the guise of “brother Azariah” instructs Tobit and his son Tobias to “do good and evil will not overtake you” (Tob 12:7), whilst in Ben Sirach Wisdom herself advises, “if you do good, know to whom you do it, and you will be thanked for your good deeds. Do good to the devout, and you will be repaid—if not by them, certainly by the Most High” (Sir 12:1–2). Wisdom also offers advice to “do good to friends before you die, and reach out and give to them as much as you can” (Sir 14:13).

This focus on “doing good” continues throughout Second Temple Judaism. As this period draws to a close, Jesus himself instructs his followers to “love your enemies, do good to those who hate you” (Luke 6:27), reminding them that “if you do good to those who do good to you, what credit is that to you?” (Luke 6:33). He further reinforces these instructions with the words “love your enemies, do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return” (Luke 6:35).

Jesus extends the image of the tree bearing fruit first spoken by John (Luke 3:8–9) with his teaching that “no good tree bears bad fruit, nor again does a bad tree bear good fruit; for each tree is known by its own fruit”, noting that “the good person out of the good treasure of the heart produces good” (Luke 6:43–45). The commitment to “doing good” which is seen in prophets, psalms, and wisdom writings, is expressly affirmed also by Jesus.

Furthermore, in Matthew’s Gospel Jesus declares that “not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven” (Matt 7:21). He tells his disciples they are “the light of the world” and then says, “let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works” (Matt 5:14-16). Later in that Gospel, he makes it clear that those doing this “will of my Father” by performing “good works” are those who feed the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, welcome strangers, clothe the naked, take care of the sick, and visit those in prison (Matt 25:35–36).

This, of course, itself draws on the guidance provided by the post-exilic prophet whose words are included in the book of Isaiah, posing the rhetorical question about “the true fast”: does it not include, amongst other things, “to share your bread with the hungry, and bring the homeless poor into your house; when you see the naked, to cover them, and not to hide yourself from your own kin?” (Isa 58:6–7). And this is how Peter remembers Jesus when he preaches to Gentiles in Caesarea about “how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and with power; how he went about doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil, for God was with him” (Acts 10:38).

Followers of Jesus who wrote letters to encourage and instruct other followers in the next few decades repeat the same instruction: “see that none of you repays evil for evil, but always seek to do good to one another and to all” (1 Thess 5:15); “do not neglect to do good and to share what you have” (Heb 13:16); “let those suffering in accordance with God’s will entrust themselves to a faithful Creator, while continuing to do good” (1 Pet 4:19).

Even Paul notes that “to those who by patiently doing good seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life” (Rom 2:7), while a later writer of the first century CE evoking the authority of Paul includes amongst the requisite qualities of a widow that she is “well attested for her good works, as one who has brought up children, shown hospitality, washed the saints’ feet, helped the afflicted, and devoted herself to doing good in every way” (1 Tim 5:10). Finally, another letter writer concludes that “it is better to suffer for doing good, if suffering should be God’s will, than to suffer for doing evil” (1 Pet 3:17). “Doing good” is a persistent biblical motif.

Acts of charity

Closely related to this is the statement that Tabitha was known as one who performed “acts of charity” (Acts 9:36). This, too, is a strong biblical theme. The word translated by the NRSVUE as “acts of charity” is ἐλεημοσυνῶν (eleēmosunōn), which derives from the root word meaning “to have mercy”—a quality that is advocated for at various places in scripture. In other translations, it is rendered “almsdeeds” (KJV, ASB), “acts of mercy” (WEB), “compassionate acts” (CEB), or “helping the poor” (GNB, NIV).

Mercy was a quality seen in God by the Israelite prophets. Isaiah declared that “the Lord waits to be gracious to you; therefore he will rise up to show mercy to you, for the Lord is a God of justice; blessed are all those who wait for him” (Isa 30:18). Hosea says that the Lord promises Israel, “I will take you for my wife in righteousness and in justice, in steadfast love, and in mercy” (Hos 2:19).

Jeremiah tells the returning exiles that God has said, “Is Ephraim my dear son? Is he the child I delight in? As often as I speak against him, I still remember him. Therefore I am deeply moved for him; I will surely have mercy on him” (Jer 31:20). and Habakkuk prays, “in wrath may you remember mercy” (Hab 3:2). And in a recurring song various writers affirm that “the Lord is gracious and merciful” (Joel 2:13; and see Exod 34:6; Num 14:18; Neh 9:17b; Ps 145:8–9; Jonah 4:2; as well as 2 Kings 13:23; 2 Chron 30:9).

Many psalms contain an indication that God was seen to be merciful (Ps 69:16; 86:15; 103:8; 111:4; 116:5; 119:156; 145:8) and a number of times, the psalmist prays “be merciful to me, O God” (Ps 57:1), “be mindful of your mercy” (Ps 25:6), “do not, O Lord, withhold your mercy from me” (Ps 40:11), or simply “have mercy on me” (Ps 51:1) or “on us” (Ps 123:3). Of course, in Christian tradition, it is the simple prayer, “Lord, have mercy”, that draws on this tradition; and in the original Greek, kyrie eleison, the verb is derived from the same root word found at Acts 9:36 (“acts of charity”, eleēmosunōn).

It is mercy for which the prophets consistently advocated. Zechariah declared that the Lord is instructing Israel, “render true judgments, show kindness and mercy [hesed] to one another; do not oppress the widow, the orphan, the alien, or the poor; and do not devise evil in your hearts against one another” (Zech 7:9–10). Micah asked his potent question, and then answered, “to do justice, to love mercy [hesed] ” (Mic 6:8). Hosea offered this clear summation: “I desire mercy [hesed], not sacrifice” (Hos 6:6).

It is this last saying that Jesus twice quotes (Matt 9:13; 12:7), both times in rabbinic-style disputations with scribes and Pharisees. This usage indicates that he saw this text as a proof text which could be used to conclude such argumentative debates. He continues the prophetic commitment to “doing mercy” in everyday life. In the final amd most aggressive interaction between Jesus and these Torah teachers, he berates them for their skewed priorities, and identifies “justice and mercy and faith” as “the weightier matters of the law” (Matt 23:23).

In the same Gospel of Matthew, Jesus affirms that the merciful are blessed, “for they will receive mercy” (Matt 5:7), and concludes his parable of the unforgiving servant by having the master declare to him, “should you not have had mercy on your fellow slave, as I had mercy on you?” (Matt 18:33).

Then, in telling a much-loved parable found only in Luke’s Gospel, Jesus responds to the lawyer wondering “who is my neighbour?” by telling a story about a wounded man and three passers-by, and ending with the question, “who do you think was the neighbour?”—to which the lawyer declares, “the one who showed him mercy” (Luke 10:37). Luke, of course, had highlighted the quality of God’s mercy in the songs that appear in the opening chaps of his Gospel (Luke 1:50, 54, 58, 72, 78).

Finally, James the brother of Jesus offers a succinct summation of the importance of mercy: “mercy triumphs over judgement” (James 2:13), while the short letter of Jude concludes by adjuring those who hear it to “have mercy on some who are wavering … and have mercy on still others with fear” (Jude 22–23). Mercy, as a quality which is evident in the lives of followers of Jesus, continues as a clear theme in the works written by his followers.

However, perhaps the weight of understanding of what “mercy” means as Christians read the New Testament has shifted to a sense of mercy as “loving forgiveness and acceptance”, whether by God or by others, rather than mercy as “acts performed in love to assist people in need”.

Tabitha (or Dorcas)

So, to return to Tabitha (or Dorcas), “the gazelle” (which is what her names means, both in Aramaic and in Greek): she was a disciple who was known for the fact that she was “devoted to good works and acts of charity” (Acts 9:36). She was a faithful, diligent, compassionate person, attending to the scriptural injunction, repeated and reinforced by Jesus, to “do good” and to carry out “acts of charity” in the knowledge that the Lord God “desires mercy, not sacrifice”.