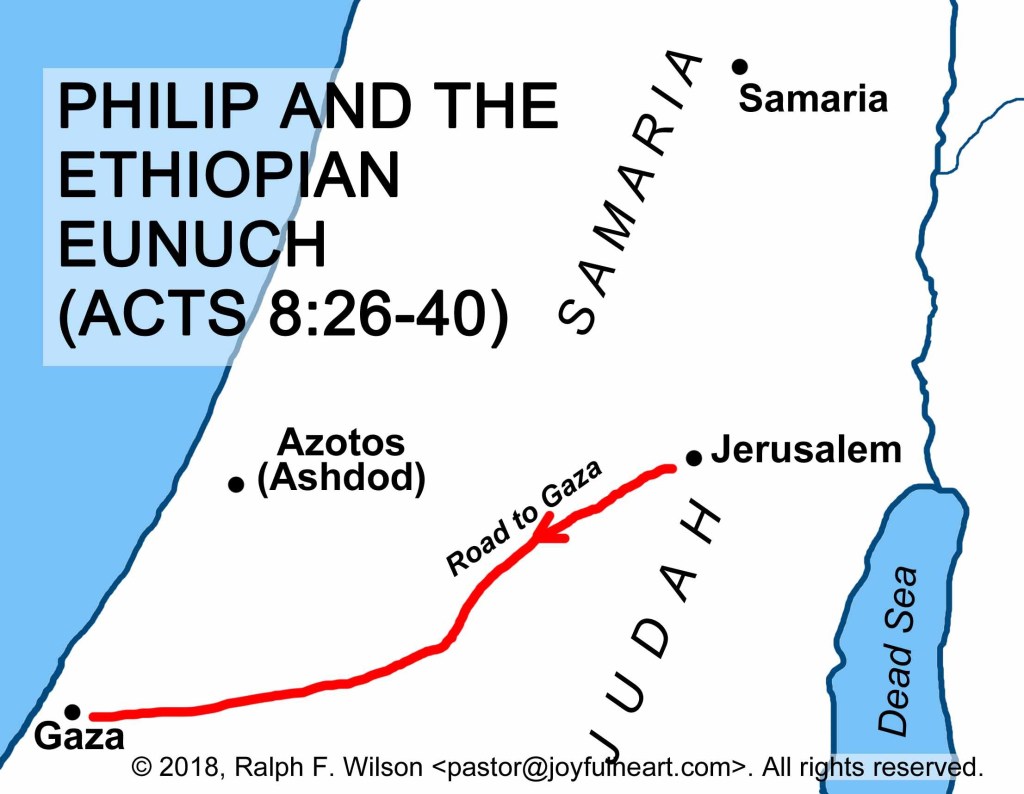

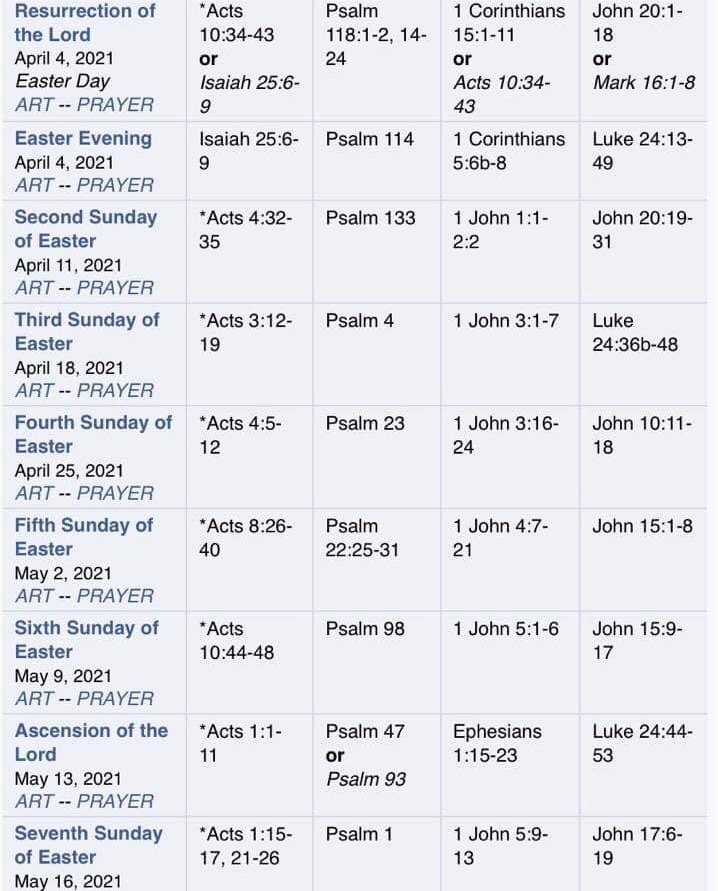

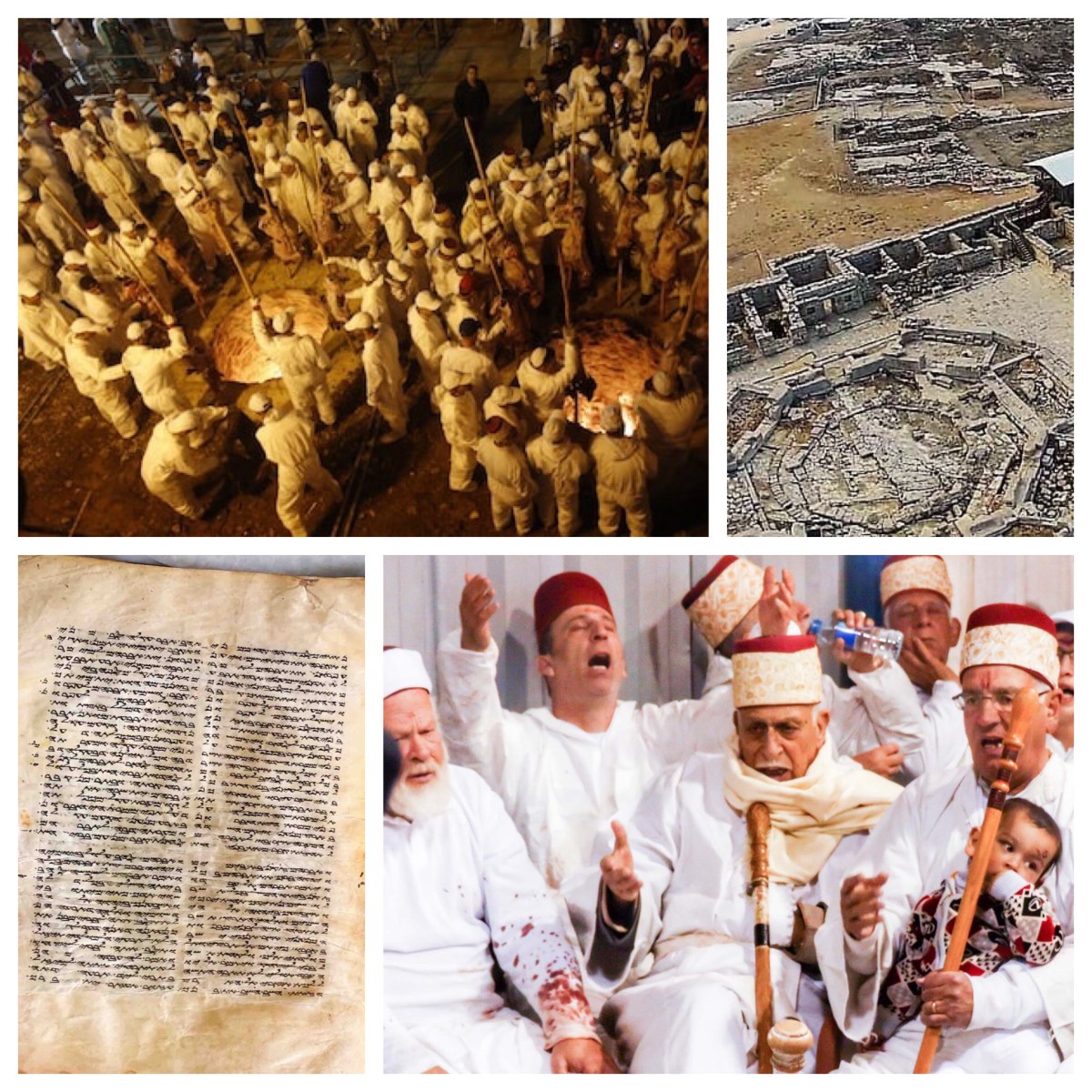

The reading from Acts offered this Sunday takes us to the edges. The man who encounters Philip is from Ethiopia. The Israelites regarded Ethiopia as the furthest extent of the earth in the south-westerly direction (Isa 11:11-12). I’ve already pondered whether this passage might provide a clear Lukan pointer to how the Gospel went “to the end of the earth” (see https://johntsquires.com/2021/04/27/edging-away-from-the-centre-easter-5-acts-8/)

Although the man was a Gentile, he was returning from worship in Jerusalem (8:27); he is probably thus the first of a number of proselytes who appear in the narrative of Acts (10:2; at 13:50; 16:14; 17:4,17; 18:7).

He is travelling in the wilderness; the place where, by tradition, God could be encountered in a new way, a way that deepens faith and sharpens understanding. The journey through the wilderness figured in the songs of Israel, being regularly recalled in the Psalms (68:7, 78:15-20, 40, 52, 95:8, 106:14-33, 136:16). It also appears in various prophetic oracles (Isaiah 40:3-5, 41:17-20, 43:19-20, Jer 2:6, 31:2-3, Ezekiel 20:8b-21, Hosea 13:4-6, Amos 2:9-10, Wisdom of Solomon 11:1-4) and occasional narrative references.

The exodus from Egypt and the subsequent wilderness wandering, provided the foundational story for Israel, from long ago, and still through into the present. Journeying through the wilderness is how Israel encountered God, deepened their faith, and shaped new ways of obedience.

The wilderness was where Israel met God; where Israel’s commitment was tested; where Israel’s faith was shaped. And as the story continues, that is exactly what happens for the man from Ethiopia. In the wilderness, he encounters God, and is welcomed into community.

*****

However, when he was in Jerusalem, this man from Ethiopia would have been barred from entering the temple precincts because he was a eunuch (Deut 23:1). In the eyes of the Law, he was not perfect, and thus not able to present himself directly before the Lord. He could approach the temple, but not take part in its rituals.

And yet, we see that the man was reading from the book of the prophet Isaiah—from the Hebrew Scriptures. He was reading of the trials of the servant, suffering humiliation and injustice, before being sent to his death (Isa 53:7-8). Philip, of course, relates this poem to the story of Jesus.

But once Philip has left the man, I wonder: did he keep on reading?

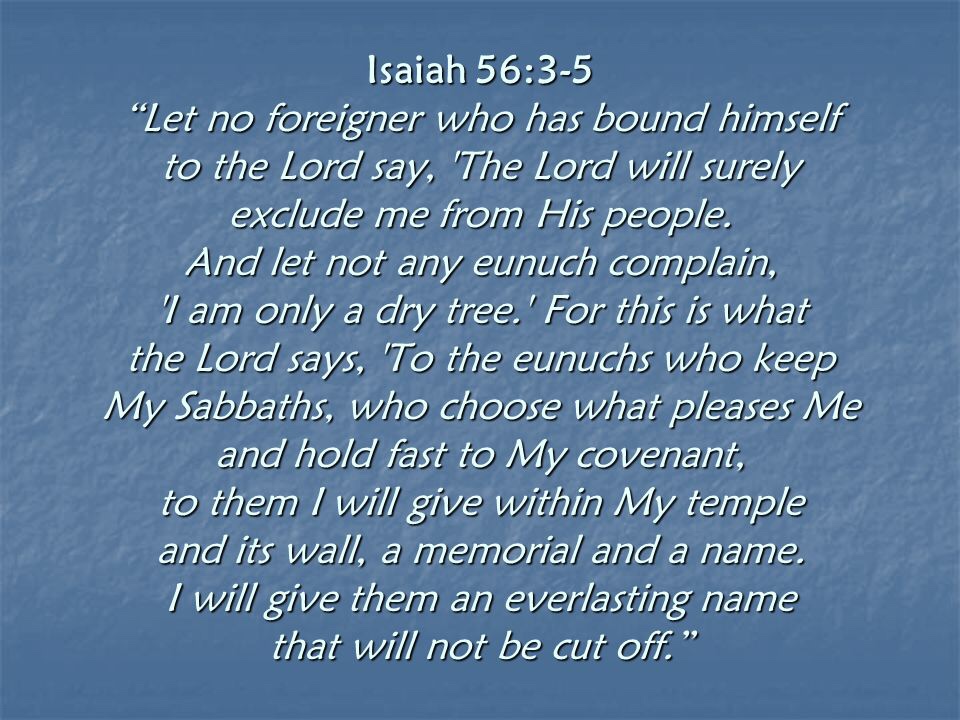

If he had done so, he would fairly soon have come to this striking passage in chapter 56:

Do not let the foreigner joined to the LORD say,

“The LORD will surely separate me from his people”;

and do not let the eunuch say, “I am just a dry tree.”

For thus says the LORD: To the eunuchs who keep my sabbaths,

who choose the things that please me and hold fast my covenant,

I will give, in my house and within my walls,

a monument and a name better than sons and daughters;

I will give them an everlasting name that shall not be cut off.

And the foreigners who join themselves to the LORD,

to minister to him, to love the name of the LORD,

and to be his servants, all who keep the sabbath,

and do not profane it, and hold fast my covenant—

these I will bring to my holy mountain,

and make them joyful in my house of prayer;

their burnt offerings and their sacrifices

will be accepted on my altar;

for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples.

Thus says the Lord GOD, who gathers the outcasts of Israel,

I will gather others to them besides those already gathered.

What an amazing passage! What a delightful expression of the gracious opening-up from the old, valued traditions of Israel, to the new, more expansive, more inclusive community of faith. Outsiders, foreigners, even eunuchs, will be welcome in the house of the Lord. They will be gathered in, accepted, valued, and loved. They will be integral parts of the community of faith.

The story of Philip and the wealthy, privileged court official from Ethiopia is a story that moves this gracious welcome of God, promised in Isaiah 56, into a reality, as the story of Acts 8 is told. Coming from another nation, coming as a man considered not to fit into the predetermined categories of gender and purity in the culture of the time, Philip’s welcoming of this Ethiopian eunuch challenges the categories, opens the doors, and invites into the centre, this person from the edge.

Whether or not the man from Ethiopia continued reading until he encountered this passage in Isaiah 56, the story recounted in Acts 8 clearly indicates that he was welcomed into the community of faith.

*****

Here is the word of God for us, today. Tradition is important. History cannot be denied. Our inheritance is significant. We bring all of this into our life today, as a community of faith. And yet, the driving dynamic in this story is about the acceptance of the outsider, the integration of the edges into the centre, the reaching out for fresh and new expressions of faith.

This is a pivot story, taking us from the central religious site of the people of Israel, the Temple, in the capital of the nation of Israel, Jerusalem; out on the road, into the wilderness, heading out towards the edge of the known world, to the ends of the earth, with a man who came from the edges, from a land at the ends of the earth, of a different religion and culture, and of uncertain gender identity.

The story actually ends with Philip in Caesarea (8:40), which is where Peter preaches and the Spirit moves amongst Gentiles (10:44-48; 11:15-18). It is another pivotal location in the overarching story of Acts. This is where God provokes the leadership of this movement to reach out and encompass new people, different people, into the community of faith.

So this is the man who was baptised by Philip during his wilderness travels: a man on the edges, out of place, not fitting the expected “normal” categories. “What is there to prevent me from baptising you?”, Philip asks the man who has read scripture, asked questions, received answers, engaged in deepening engagement with the Gospel—and then, was baptised, dunked into the water, welcomed into the community of faith that was shaped by the teachings and stories of Jesus of Nazareth (8:36-38).

From the edges, into the centre. This is who we are to be, as church. Open to those we perceive as outsiders; inviting them in to become integral insiders. Accepting those whose patterns of life we might question—in his case, a person whose gender is uncertain, up for question—maybe even perceived as deviant, by those hardliners who hold fast, without breaking their grip, to the dogmatic way that they understand their faith.

In the congregation where I worship regularly, we welcome all. We especially welcome rainbow people—people who do not readily identify with the dominant pattern of heterosexual male or female, but who name their sexual attraction to others as meaning that they are gay or lesbian, who are grappling with the challenge of being intersex, who have travelled the pathway of transgender identity, who are bisexual or asexual, or who happily adopt the once-derogatory term of being “queer” and use it in a positive, affirming way.

Within the total population of human beings, is a wide range, and amazing diversity, a kaleidoscope of sexual preferences and gender identities; and such diversity is represented within the community of the Tuggeranong Valley, and within the Tuggeranong Uniting Church community. And that is precisely the way that church is supposed to be.

And as we continue to reflect on this passage, we might also remember that this is but one way, this is but one sector in the community, to which we might carefully and intentionally open our doors. Alongside rainbow people, we are called to offer welcoming hospitality to families where issues of faith and spirituality are live and important, but for whom the traditional patterns of church do not satisfy; to those who have been scarred by traumatic experiences in life and who are looking for validation and valuing, for a safe place to belong with no questions asked and no demands imposed; to any who seek the deeper things of the dimension of spirit in their own lives.