This essay and the one before it in a previous blog is written by my friend and colleague, the Rev. Dr Geoff Dornan, offering a Christian ethical perspective on a recent controversy (one of so, so many) in the United States of America. Geoff has a PhD in Philosophy, Theology & Ethics from Boston University, USA. He is currently serving as Minister in Placement at Wesley Uniting Church in Canberra, ACT.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the first essay, I traced the events of the conflict between, the American Vice President J.D Vance and the Vatican at the beginning of 2025 – in particular the former Pope, Francis I – when Vance offered a theological and moral defence of the Trump Administration’s policy of forced mass deportations without due process, in defiance of the fifth and fourteenth amendments of the American constitution.

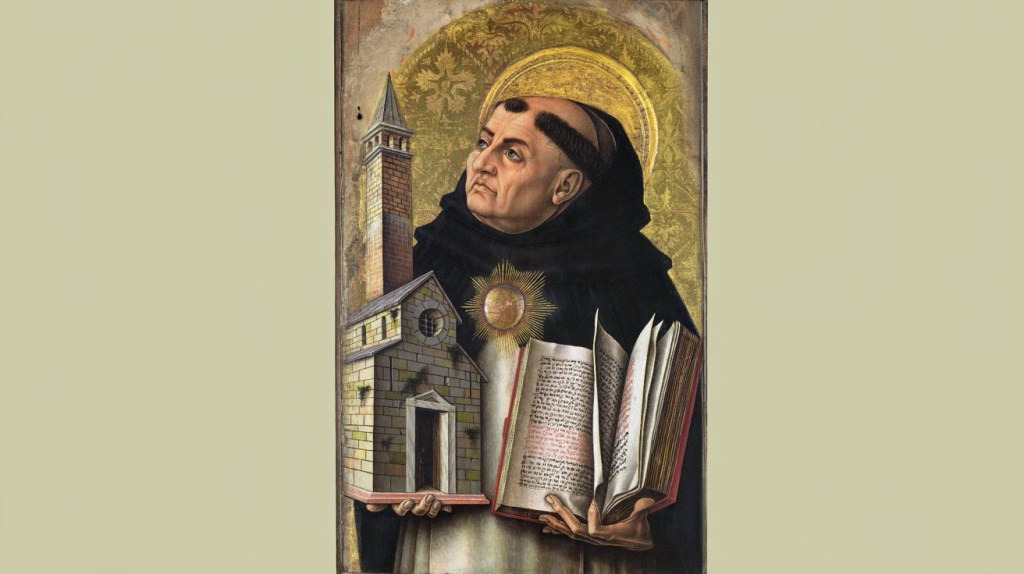

The defence that Vance offered was grounded in the thought of St Thomas Aquinas’ Ordo Amoris, the right ordering of love. In that paper, I concluded that Thomas does not offer any such defence to the Trump Administration’s policy or practice. I also suggested that the Ordo Amoris is not a sufficient basis in and of itself for any modern discussion of the issue. I noted that a millennium has passed since Thomas offered his rationale on love of the neighbour, and that any adequate discussion must consider developments since.

See

In this essay, I shall explain those developments. My contention is that if J.D. Vance had been cognizant of them, he would have been more cautious in his ill-considered action of grasping Thomas for his own political purposes. The first developmentconcerns the change in the purpose and service of Catholic theology. The second aspect concerns the rise of Catholic Social Teaching in the last 100 or so years, that has helped redefine that purpose as an enterprise directed to the poor of history: that which is sometimes referred to as the Gospel’s “preferential option for the poor”.

2. WHAT SORT OF SERVICE MAY THEOLOGY RENDER?

Historically speaking Catholic theology has been quite different to its Protestant counterpart. The latter has been directed to the believer, as they work out their faith in the world. Protestant theology has taken many forms – evangelical, liberal, dialectical, existentialist, political, liberationist, feminist, black and process – to name but a few.

Catholic theology on the other hand has been less haphazard, more tightly organized, and better managed, but not for that matter, any less prone to conflict. In reading Catholic theology, one can understand both the official line approved by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith and the dissident lines to which the Dicastery responds. In Catholic theology the parameters are always clearer.

Now, the great debate in Catholic theology which has repeatedly surfaced over the last 120 years or more has concerned its purpose. For much of Catholic history, theology had been addressed to the theologians, not the faithful as such. This took a particularly pellucid, explicit form in what was called neo-Thomism, where theology was a conversation between intellectuals.

Grounded in mediaeval thought, neo-Thomism was really a form of romanticism that lasted until the middle of the 20th century and still prevails among some conservative Catholic circles. It held that theology was the queen of the sciences, a super-science, that offered security and certainty from the instability and vicissitudes of the volatile, erratic human sciences. It held to the immutability of Catholic teaching, excusing itself from the obligation of adapting to modern times.

José Comblin, a Belgian priest who spent many years in Latin America in mission and teaching, put it this way: “It was an intellectual realm living on the margins of world history, anachronistically reconstructing some total form of learning and resurrecting a mediaeval world in the very midst of a technological and scientific society”.

Fr. José Comblin

Unsurprisingly, neo-Thomism, in considering theology as a detached, immutable and contemplative exercise, considered God in the same way. God was seen as removed from the world, utterly ‘other’ in transcendence, to such an extent that divine grace never really touched the world. Grace and nature remained strangers to each other. There was a gap between them.

Perhaps the biblical reading in John’s Gospel where Jesus is reported to have said, “My kingdom is not of this world” (18:36) in his interrogation under Pilate, typifies this gap. Speaking theologically, in neo-Thomism, divine grace is extrinsic to, stands outside of concrete human experience, because God is understood to eclipse, surpass creation.

The problem with this interpretation of Christianity was that the utterly transcendent God remained almost irrelevant to human beings and human experience. Grace and salvation – the latter explained as “the tangible experience of grace’s results in our lives”, were reduced, diminished to the interior spiritual life, ignoring altogether those crucial human dimensions of the social and the political.

So, the problem for Catholic theology in a nutshell was that it was caught between two worlds: the natural and the supernatural, earth and heaven, with no real link, connection, or affiliation between them. The basic theological ideas of neo-Thomism were mere abstractions. Theology offered the service of debating abstract metaphysical ideas for the cultivated erudite Catholic elites, but little more.

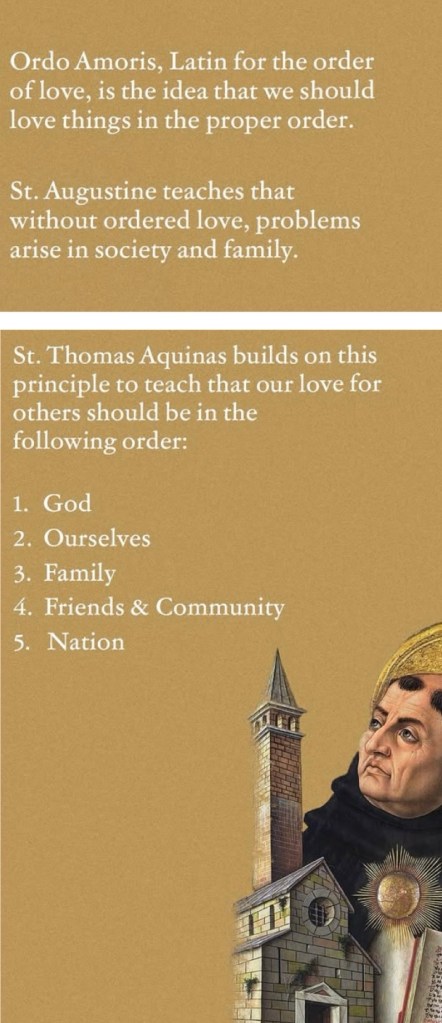

But then things changed. This separation of nature and grace, this misunderstanding of salvation as esoteric or super-spiritualised, never social or political, was finally addressed in modern Catholic thought in the reforming council known as Vatican II, (1st October 1962 to 8th December 1965). In essence, Vatican II was a revolution in the Roman Catholic church, with its spirit of aggiornamiento – the Italian for renewal or updating. This renewal led to the construction of a new connection between grace and salvation, with human experience and social justice.

In turn, this dramatic change stimulated Latin American Liberation Theology in the 1960s and modern German Political Theology at about the same time. In remarking upon this new connection, one of the great popes of the 20th century, Paul VI – to whom it fell to continue the reforms of Vatican II – wrote in his apostolic exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi, “On Evangelization in the Modern World” (December 8th, 1975),

“The Church…has the duty to proclaim the liberation of millions of human beings, many of whom are her own children – the duty of assisting the birth of this liberation, of giving witness to it, of ensuring that it is complete. This is not foreign to evangelization. (EN.30)

3. CATHOLIC SOCIAL TEACHINGS

If the rethinking of the relationship between nature and grace led to a recasting of the connection between salvation and social justice, Catholic Social Teachings were the vehicle through which this occurred. I have already referred to Pope Paul VI’s document Evangelii Nuntiandi, which is part of Catholic Social Teaching. But we need to dig deeper if we are to bring to light J.D. Vance’s misadventure in poor theology and poor politics.

Let us then ask the question, what are Catholic Social Teachings? Most Protestants know nothing about it, but then again, few Catholics do either. How did they begin and how do they operate today?

A. ITS ROOTS

Catholic Social Doctrine, today referred to as Catholic Social Teachings, began less as an enlightened project of the Catholic Church and more a defensive strategy at the end of the nineteenth century, as the Catholic Church, submerged in the first industrial revolution, fought against the rise of Marxist Socialism, and the exodus of the European working class from the pews.

This response in the face of exploitative capitalism, nevertheless, did not suggest a sudden rethinking of the tradition as a whole. Rather, the conservative Catholic dogmatic tradition, centred in Thomas Aquinas continued. In fact, it was reinforced, with but a few sporadic endorsements of modernity.

In keeping with this entrenched approach, in a letter of 1892, Pope Leo XIII directed all Catholic professors of theology to accept particular statements of Thomas as definitive. Where Aquinas had not spoken on a given theme, any conclusions reached, had to be in harmony with his known options and opinions. Within a generation neo-Thomism became an unquestioned and unquestionable ossified orthodoxy in Catholic educational institutions.

B. IT CONFRONTS ‘THE REAL’

As we have just read, Catholic theology maintained two quite separate streams: conservative dogmatic theology for the intellectuals, detached from the real world, and the growing presence of Catholic Social Teaching, that confronted ‘the real’, the struggles of the poor. It was a binary approach that remains today.

That said, even though Catholic Social Teachings were born in a context of obscurantism and traditionalism, it is this stream which has grown, as Rome has understood that the Catholic Church must face the problems of our age.

Let us make mention of some of the key teachings. The first encyclical, penned by no other than Leo XIII himself, entitled Rerum Novarum (New Things), called for what today are still radical measures: a passionate attack upon unrestricted market capitalism, the duty of state intervention on behalf of the worker, the right to a living wage and the rights of organized labour. This newfound radicalism changed the terms of all future Catholic discussion of social questions.

From there followed some outstanding statements: Pius XI’s Quadragesimo Anno, (On Reconstruction of the Social Order) in 1931; Exsul Familia, (The Émigré Family) in 1952; John XXIII’s, Pacem in Terris, (Peace on Earth) in 1963; Vatican II’s Gaudium et Spes (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World) in 1965; Paul VI’s Popolorum Progressio, (On the Development of Peoples) in 1967; The International Synod of Bishops, Justicia in Mundo, (Justice in the World) in 1971; John Paul II’s Laborem Exercens, (On Human Work) in 1981; and Centesimus Annus, (On the Centenary of Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum, looking back and updating thought about Worker’s Rights) in 1991.

In all these encyclicals up till the turn of the twentieth century, the recurring themes were those of the dignity of the human person, the priority for the immigrant and refugee, the priority of labour over capital, the centrality of the common good, and the universal destiny of all goods of creation to serve all peoples, not just some.

Can we then speak of a difference between Thomas and Catholic Social Teachings? Clearly yes! Catholic Social Teaching’s reading of the order of love, how love is to be structured in the world, is more naturally comprehensive; deeper than that of Thomas. And how could it be otherwise as theology must respond to change; especially that of a larger and interdependent world, where the very concept of the neighbour has broadened.

CONCLUSION

So, what may we say? What may we conclude?

The fundamental point that must be made here is that J.D. Vance’s approach to Christian theology is both too narrow and too defensive. To justify the Trump Administration’s policy and practice regarding the forced mass deportation of non-US citizens without due process, he seizes upon Ordo Amoris but as we saw in the first paper, notwithstanding Thomas’ weaknesses, Vance fails to honour Thomas’ integrity of thought.

More importantly, Vance fails to read theology through an historical lens, ignoring the entirety of Catholic Social Teachings, which have been around for some time: over one hundred years. It is a similar approach to those who grasp a biblical text, ignoring its wider theological context and meaning, to sanction their already prejudged agenda.

Pope Francis in his communication to the U.S. bishops sums it up as he speaks of the “rightly formed conscience”, implying that it is this that is missing in the Trump Administrations’ approach.

Francis writes:

“I have followed closely the major crisis that is taking place in the United States with the initiation of a program of mass deportations. The rightly formed conscience (my italics) cannot fail to make a critical judgment and express its disagreement with any measure that tacitly or explicitly identifies the illegal status of some migrants with criminality. At the same time, one must recognize the right of a nation to defend itself and keep communities safe from those who have committed violent or serious crimes while in the country or prior to arrival. That said, the act of deporting people who in many cases have left their own land for reasons of extreme poverty, insecurity, exploitation, persecution or serious deterioration of the environment, damages the dignity of many men and women, and of entire families, and places them in a state of particular vulnerability and defencelessness.”

For Pope Francis, and as far as we may judge, the recently elected Pope Leo XIV, the Gospel concern is above all about the defence of the salvation and liberation of the poor in a hostile global pro defensio salutis et liberationis pauperum.

For J.D. Vance, on the other hand, the concern is – as we should expect – the interest of the United States within the global order. Which concern should carry greater weight in the Christian scheme of things, and how each may creatively interact with the other, if at all, remains a matter of judgment and discernment over the remaining period of the Trump presidency.