One of the passages offered by the lectionary for this Sunday, the second Sunday in Advent (Luke 1:68–79), comprises the text of a psalm-like song that is often called The Benedictus, after the opening phrase of the song in the Latin translation. The whole song resonates in every line with words, ideas, concepts from the Hebrew Scriptures. I’ve been considering that in earlier posts on this passage.

See

Luke, as we know, was writing many decades after the events he reports; he certainly wasn’t present at the time John was born, and it is most unlikely that any of the people he refers to as his sources (Luke 1:2) were witnesses to this. Rather, it is sensible for us to consider that he wrote this song, drawing extensively from the Hebrew Scriptures, and placed it in the mouth of Zechariah at what was an appropriate moment in the story that he was telling. (The story as a whole isn’t history; it is Luke’s way of introducing the figure of Jesus by placing him firmly in his historical context, as a Jew of the late Second Temple period.)

In my previous post, I have considered how God is described, and prayed to, in this song, drawing on various scriptural passages. Another way that Luke evokes scripture is when he has Zechariah sings that God “has remembered his holy covenant, the oath that he swore to our ancestor Abraham” (Luke 1:72–73). The phrase explicitly evokes comment in the ancestral narrative, when Moses fled to Midian, that “God remembered his covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” (Exod 2:24), repeated in words on the lips of the Lord to Moses, “I have heard the groaning of the Israelites whom the Egyptians are holding as slaves, and I have remembered my covenant” (Exod 6:5).

The phrase recurs in the psalm that recalls the sins committed by the people of Israel during their time in the wilderness, when “he regarded their distress when he heard their cry”, and so “for their sake he remembered his covenant, and showed compassion according to the abundance of his steadfast love” (Ps 106:44–45). Reflecting on the sins of the people of a later generation, the prophet Ezekiel reports that the Lord God will nevertheless “remember my covenant with you in the days of your youth, and I will establish with you an everlasting covenant” (Ezek 16:60). This idea lies behind the promise offered at the same time by the prophet Jeremiah, that the Lord God “will forgive their iniquity, and remember their sin no more”, and so “will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and the house of Judah” (Jer 31:31–34). Remembering and recommitting to the covenant is embedded in the scriptures.

Zechariah refers to two key characters from Israel’s ancestral stories: Abraham, in referring to “the oath that [the Lord God] swore to our ancestor Abraham” in making the covenant (v.73), and David, in referring to the “mighty saviour” that God has raised up “for us in the house of his servant David” (v.68). These are, of course, two key figures in the story of Israel, to whom much attention is given in the ancestral narratives (Abraham in Gen 12—25; David in 1 Sam 16—1 Ki 2).

Although the song is sung immediately after the birth of the son of Elizabeth and Zechariah (Luke 1:57), to be named John (1:59–63), the father celebrates the birth of his son largely, as we have seen, by celebrating the mighty deeds of God. He does note that this child “will be called the prophet of the Most High” and that he “will go before the Lord to prepare his ways, to give knowledge of salvation to his people by the forgiveness of their sins” (1:76–77). This is indeed how John is portrayed when, as an adult, he becomes active around the Jordan in calling people to repentance (Mark 1:2–8; Matt 3:1–12; Luke 3:1–18).

The one who “prepares the way” reflects the prophetic word of Malachi, who declares “I am sending my messenger to prepare the way before me, and the Lord whom you seek will suddenly come to his temple” (Mal 3:1). The fiery nature of this messenger’s language (Mal 3:2–3) is clearly reflected in John’s message of judgement (Luke 3:7–9, 16–17). That he proclaims “a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins” (Luke 3:3) guides Luke to give to his father words (1:77) that point forward to this very message.

The song ends with some observations about the response of people to what God has been and is doing. Zechariah anticipates that those who learn of this might “serve him without fear, in holiness and righteousness before him all our days” (vv.74–75). All three characteristics of this response are, of course, fundamental elements in the piety of ancient Israelites and Jews of the Second Temple period. “You shall fear the Lord your God” is a priestly refrain (Lev 19:14, 32; 25:17, 36, 43) recurring in the words Gos speaks in Deuteronomy (Deut 4:10; 5:29; 6:1, 13, 24; 10:12, 20; 13:4; 14:23; 17:19; 31:12–13) as well as in subsequent narrative books.

Holiness amongst the people is also advocated by the priests, on the basis that God is holy. “I am the Lord your God; sanctify yourselves therefore, and be holy, for I am holy … I am the Lord who brought you up from the land of Egypt, to be your God; you shall be holy, for I am holy” (Lev 11:44–45; see also 19:2; 20:7, 26). And righteousness is declared by various prophets as who the Lord God requires of God’s people (Isa 5:7: 11:4–5; 32:16–17; 52:1, 7; Jer 22:3; 23:5; Hos 10:12; Amos 5:24; Zeph 2:3).

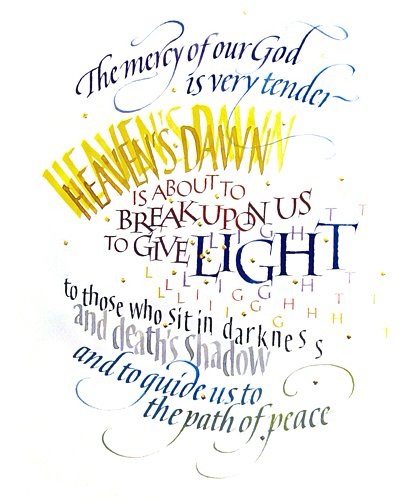

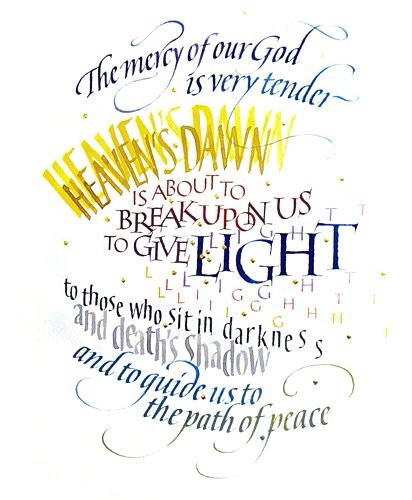

Finally, the closing verses of this song contain evocative imagery which draws from poems in Hebrew Scripture. “The dawn from on high will break upon us” (v.78) resonates with Third Isaiah’s words that “your light shall break forth like the dawn and your healing shall spring up quickly” (Isa 58:8). That dawn will “give light to those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death” (v.79) references the numerous places where light breaks into darkness (Ps 18:12; Isa 9:2; 42:16; 58:10; Mic 7:8; and see the same dynamic in the creation account at Gen 1:1–5). The phrase “the shadow of death” (v.79) alludes to “the valley of the shadow of death” in Ps 23:4.

Then, the final affirmation that this breaking dawn will “guide our feet into the way of peace” (v.79) refers to Third Isaiah again, in his lament that “the way of peace”, missing in his time, will surely come. This oracle, in fact, splices together the same ending notes that we find in Zechariah’s song: “the way of peace they do not know, and there is no justice in their paths; their roads they have made crooked; no one who walks in them knows peace. Therefore justice is far from us, and righteousness does not reach us; we wait for light, and lo! there is darkness; and for brightness, but we walk in gloom” (Isa 59:8–9).

Indeed, in the following oracle the prophet declares: “Arise, shine; for your light has come, and the glory of the Lord has risen upon you. For darkness shall cover the earth, and thick darkness the peoples; but the Lord will arise upon you, and his glory will appear over you. Nations shall come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn.” (Isa 60:1–3). Or, as Zechariah sings, “By the tender mercy of our God, the dawn from on high will break upon us, to give light to those who sit in darkness and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace.” (Luke 1:78–79).

See also