The long detour away from Mark’s Gospel draws to a close. Next week we will rejoin the story of the beginning of the good news of Jesus, Messiah (which we know as the Gospel of Mark), after having spent more than a month with the book of signs, which contains just some of “the many things that Jesus did” (which we know as the Gospel of John).

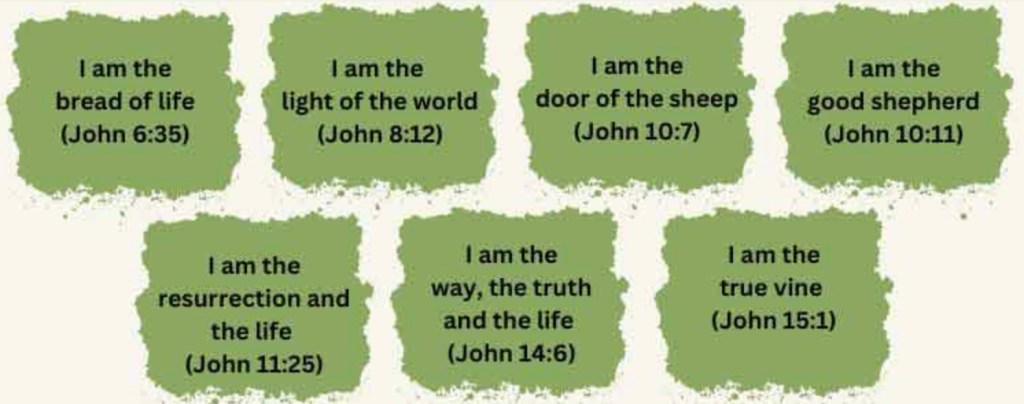

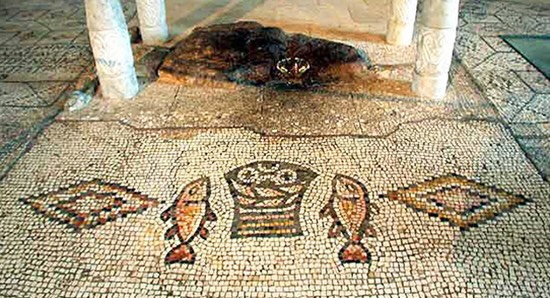

Some weeks ago, after hearing John’s version of Jesus feeding a large crowd (6:1–13), we heard a passage ending with the first declaration by Jesus, “I am the bread of life” (6:24–35). Then we heard the next section of that discourse, dealing with an elaborated midrashic exposition about that “bread of life” (6:35–51), followed by the disputes that this teaching generated with the Judaean authorities (6:51–58). This coming Sunday we hear the final section of the discourse where Jesus turns to deal with dissent from his own disciples (6:56–69).

The early section of this passage contains verses which are always controversial when they are read in worship. Last week’s passage had drawn to a close with Jesus declaring that “those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day” (v.54), before continuing on to provide a further statement: “my flesh is true food and my blood is true drink” (v.55). The language is significant; Jesus does not talk about his body (sōma), but his flesh (sarx). That continues through to v.58, and on into v.63.

The passage proposed for this coming Sunday picks up at v.56, in the middle of this discussion, and runs through to the end of the chapter. We have noted that verse 58 provides a neat conclusion to the lengthy midrashic treatment that began in v.31, with the citation of a scriptural verse and was focussed by the statement of Jesus, “I am the bread of life” (v.35, repeated at v.48). That’s a neat inclusio for the whole extended discussion.

The conclusion in v.58 rehearses this central theme: “this is the bread that came down from heaven, not like that which your ancestors ate [with reference to v.31], and they died”. Jesus then extends the imagery to cover those who are his followers: “the one who eats this bread will live forever”. That includes his disciples in the eternal state that he himself enjoys. So v.58 actually functions more like a hinge, connecting what has gone before with what then follows.

The difficulty that the disciples identify (v.60) is inherent in the language and concepts of what Jesus has said. As far back as v.51 he has stated, “the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh (sarx)”. He continued with the claim, “unless you eat the flesh (sarka) of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (v.53), intensifying the claim with “my flesh (sarx) is true food and my blood is true drink” (v.55).

The whole sequence comes to a head with the narrator’s comment that “Jesus, being aware that his disciples were complaining about it, said to them, ‘Does this offend you?’” (v.61). The Greek verb in what Jesus says is skandalidzō, which we might translate as “scandalized”. That translation well encapsulates the outrage and disgust of the disciples.

The use of the word sarx in this sequence of statements is jarring. Elsewhere in Eucharistic passages in the New Testament, Jesus refers to his body as sōma, a word which has connotations of materiality, earthiness. The more physical term, sarx, refers to flesh. Eating the body of Jesus is one thing—already a difficult enough concept—but eating the flesh of Jesus makes it sound like a cannibalistic feast (as later critics of the Christians argued).

Some commentators maintain that the use of the more basic term sarx reflects the incarnational emphasis of this Gospel, already set forth with clarity at 1:14, “the Word became flesh and lived among us”. In that same section of text, one description of human beings is “those born of the will of the flesh”, so that argument does carry some weight. James Dunn (in a short article in NTS 17, 1971, p.336) says that the choice of vocabulary is “best understood as a deliberate attempt to exclude docetism by heavily, if somewhat crudely, underscoring the reality of the incarnation in all its offensiveness”. However, I find it somewhat unusual that the author of this Gospel would operate in this rather clumsy manner.

Added to this observation, we might note that the word that is used here for “eating” is a very base word, most commonly referring to “munching” or “chewing”, as the BAGD Lexicon notes. This verb, trōgō, is used in quick succession in verses 54,56,57,58, and also at 13:18, where it is in a quotation of Ps 91.10, “the one who ate my bread has lifted his heel against me”. This vocabulary, then, is quite distinctive; it, too, is quite earthy and base.

A common interpretive question is whether the references to eating bread and drinking blood in this latter part of John 6 were intended to be eucharistic—that is, to evoke the moment in the last supper that Jesus ate with his disciples when he broke the bread and shared it with them? On face value, that seems unlikely. John’s Gospel does have Jesus sharing a last meal with his disciples (from 13:1 onwards), but there is no mention of any breaking of bread and drinking of wine in the formal pattern found in the Synoptic Gospels. Rather, in that meal the focus is initially on washing feet (13:3–5), before Jesus offers a long, extended “farewell discourse” (or, more accurately, two such discourses) stretching through until his long prayer in ch.17.

The recollection of the last meal of Jesus is clearly attested in four separate New Testament books. The earliest to write about it, Paul, recalls the tradition that he received, in which Jesus said “This is my body, which is for you; do this in remembrance of me” (1 Cor 11:24). Mark recalls the words of Jesus as the simple “Take, this is my body” (Mark 14:22), while Matthew, utilising Mark’s account, slightly extends this to “Take, eat; this is my body” (Matt 26:26). The latest of the four, the Lukan record, has more of an evocation of Paul’s version, “This is my body, which is given for you; do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19). All four passages have Jesus use the word sōma, body. In John 6, however, the word sōma is nowhere to be found, unlike in John’s account, where Jesus is reported as using the word “flesh” (sarx).

Raymond Brown, in his thorough analysis of this Gospel and working within his hypothesis regarding the complex formation of the text through various stages, is clear: when compared with verses 35–50, “verses 51–58 have a much clearer eucharistic reference” (Brown, The Gospel according to John, vol.I pp.290–91). However, he concedes that this reference is “scarcely intelligible in the setting in which it now stands”. In Brown’s view, the various redactional layers in the text means that the original intention has been lost.

Writing decades later, Australian scholar Francis Moloney notes that, in true Johannine style, “the midrashic unfolding of the verb ‘to eat’ naturally led to the use of eucharistic language to insinuate a secondary but important theme” (Sacra Pagina: The Gospel of John, p.224). For Moloney, the occurrence of regular eucharistic celebrations, even in those ancient times, would evoke and bring forth the eucharistic sense that underlies the passage.

Moloney and Brown are Roman Catholics; we might expect such commentators to lean towards the eucharistic understanding. Coming from a rather different ecclesial context (as an evangelical Baptist), however, George Beasley-Murray admits that “neither the Evangelist nor the Christian readers could have written or read the saying without conscious reference to the Eucharist” (Word Biblical Commentary: John, p.95).

One final comment on this issue from me: we know that in the early centuries of Christianity, there was much passing on of tradition by word of mouth; for some (such as Papias) oral traditions were even to be preferred over written documents. The context was fluid, so the possibilities for variations and differences was much higher than our contemporary context, in which written texts are precise and need to be quoted exactly (at least in academic and careful liturgical contexts). The author of John’s Gospel could well be working from a slightly different tradition and saw no constraints in developing it in the direction that particularly wanted to take it.

The whole chapter draws to a close, after the intense explanation of eating and drinking that Jesus offers, with his response to the offence taken by the disciples, as he reiterates the “spirit” emphasis that was central in his encounters with the Pharisee in Jerusalem (3:4–8) and the woman in Samaria (4:23–24). Indeed, since the Spirit had descended upon Jesus (1:32–33), it is now the one “whom God has sent [who] gives the Spirit without measure” (3:34). So he declares, “it is the spirit that gives life … the words that I have spoken to you are spirit and life” (6:63). Jesus says more about the Spirit later, in his farewell discourses (14:15–17, 25–26; 15:26; 16:12–15).

Of course, in the very same breath, Jesus dismisses the flesh as “useless” (6:63), thereby relativising the impact of the incarnational affirmation of 1:14 that we have noted above. Jesus here presses the importance of faith, ultimately, in what God is doing: “no one can come to me unless it is granted by the Father” (v.65). This is the framework of reality that he operates in, and into which he invites his followers.

I am wary of reading this as a kind of proto-Calvinist claim about predestination. Rather, I think it reflects the sectarian nature of the community for which the author is writing (as I have noted in earlier posts). The group was battered by the conflicts they had experienced, culminating in their expulsion from the synagogue. They needed to recall the story of Jesus in a way that encouraged them and affirmed their own sense of holding to “the truth”.

Through this long and complex chapter, then, Jesus has been building a picture of the “symbolic universe” in which he, the disciples, and his opponents are located. This is the context in which the members of the community understood themselves to be. All that takes place is set within the overarching framework of God’s work, which is what Jesus is called to do (4:34; 17:4) and what his followers are called to undertake (6:29–30; 9:4). The whole thing becomes mutually self-reinforcing.

The teachings they have heard from Jesus, however, are portrayed as being off-putting to some of the disciples, who “turned back and no longer went about with him” (6:66). The division amongst humanity, signalled from very early in the Gospel (1:10–13) and acted out in the extended conflict with the Judaean authorities which runs through the whole Gospel, here infiltrates the company of disciples. Some continued with Jesus, some departed from him.

Jesus puts “the twelve” on the spot, asking them, “do you also wish to go away?” (v.67). Simon Peter here speaks on their behalf (as he does often in the Synoptics) to affirm faith in Jesus: “you have the words of eternal life; we have come to believe and know that you are the Holy One of God” (6:69). This is the Johannine equivalent of the confession that Peter speaks, on behalf of the disciples, at Caesarea Philippi (Mark 8:29; extended at Matt 16:16; see also Luke 9:30). In John’s Gospel, however, this high point of confession is repeated later in the narrative by Martha, who extends her statement even further: “I believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world” (John 11:27).

The chapter ends with the gathering of ominous dark clouds, as Judas is identified as the one who was going to betray Jesus (v.71)—quite dramatically, he is identified as “a devil” (v.70). This is explained later, in the introduction to the last meal scene, as “the devil had already put it into the heart of Judas son of Simon Iscariot to betray him” (13:1). The lines are drawn. And so the ultimate end of what is being narrated about Jesus is signalled.

For previous blogs, see

and on the whole sequence of this chapter