The letter which we call 2 Corinthians is comprised of three main sections, each of which has its own distinctive focus. In the first section of the letter (1:1–7:16), Paul and Timothy write to offer consolation and hope to the people who are part of the community of followers of Jesus in Corinth. It is clear that members of the community have undergone some difficult times; Paul empathises with them, drawing on his own experiences, as a way of offering a message of hope to the believers in Corinth.

In a second main section (8:1–9:15), Paul addresses a very practical matter—the collection of money which he was making amongst the churches of Achaia and Macedonia, which he was planning to take to Jerusalem for the benefit of the believers there who had been experiencing difficulties. Then, in a third main section (10:1–13:13), Paul’s tone is markedly apologetic, as he writes in severe tones to defend himself in the face of criticisms which have been levelled against him in Corinth.

The lectionary offers us an excerpt from the first main section (3:12—4:2) for the Festival of the Transfiguration, this coming Sunday. It is obvious why this excerpt is suggested, since the argument includes a reference to the passage from Exodus which will also be read and reflected upon this Sunday. “The people of Israel could not gaze at Moses’ face”, Paul and Timothy note, “ because of the glory of his face” (3:7).

They go on to contrast this with the consequences of that one scene in the life of Jesus that the Synoptic Gospel writers later tell in narrative detail, arguing that “all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another” (3:18). That is, whilst the transformation of Moses was not able to be witnessed by the people of Israel, the transformation of Jesus is shared in abundance with the followers of Jesus. It’s a stark contrast.

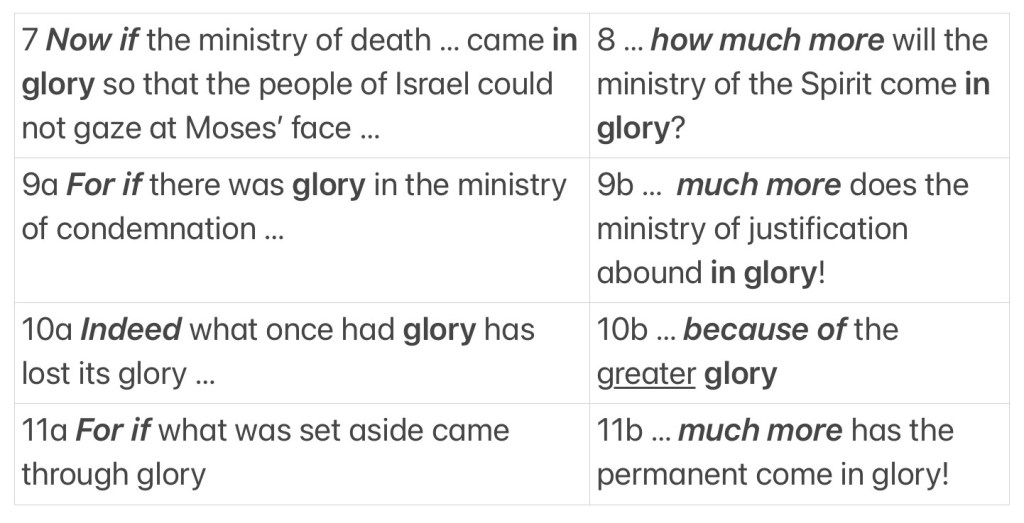

The fundamental point in what Paul and Timothy argue here is thoroughly polemical. They press, again and again, on the difference between the Exodus scene and the scene that we know as the Transfiguration of Jesus. They use the typical juxtaposition of two opposites that characterized the rhetorical style of the diatribe (and which we find in a number of other letters of Paul).

The juxtapositions have begun in the preceding verses. In full polemical flight, Paul presents himself and Timothy as a “ministers of a new covenant”, which defines as “not of letter but of spirit”, continuing with the explanation “the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life” (3:6). He then contrasts “the ministry of death” with “the ministry of the Spirit” (3:7–8). The former is “chiseled in letters on stone tablets”, whilst the latter brings “glory”. It is clear where Paul’s preference lies.

This leads to two new, snappy slogans: “the ministry of condemnation” and “the ministry of justification”, which are then contrasted (3:9–11). The former did have its element of glory—the face of Moses shone with God’s glory—but “what once had glory has lost its glory”. Paul and Timothy advance the argument through a series of direct contrasts.

How this “loss of glory” occurred, it seems, was “because of the greater glory; for if what was set aside came through glory, much more has the permanent come in glory!”. The argument, somewhat convoluted, seems to be that the former, seemingly inadequate, glory is completely overshadowed by the later, far more powerful glory.

Paul launches then into an attack on that former ministry which becomes quite vindictive. Moses is criticized for covering his face so that the people of Israel could not “gaze at the glory” that he was concealing (v.13). The minds of the people thus were “hardened”; indeed, even “to this very day”, he says, that hardening of heart remains when they hear “the reading of the old covenant” (3:14). In contrast to this deadly scenario, “in Christ” that veil is lifted, that hardening of heart is softened “when one turns to the Lord” (3:16). The exultant conclusion is that “all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another” (3:18).

There is great danger in these words. The danger is that we absolutise them as validating any criticism, all criticism, of Judaism as a religion; that we value Christianity by demeaning and dismissing Judaism. To do this would mean that we would ignore the reality that these words were written in a context quite different from our own, addressing a situation which may (or may not) have had little do with our own situation. That wider context and that specific situation are very important as we interpret this passage (and, indeed, any passage in the Bible).

We are witnessing today, both in Australia and in many places around the world, a rise in antisemitic words and actions. To be sure, the violent and illegal actions ordered by the current Israeli government against the residents of Gaza (the most recent in a long and tragic sequence of similarly illegal and aggressive actions over decades) has probably inflamed such antisemitism.

But criticism of the policies of one nation state should not be used to foment hatred against a whole people, whether they live in that nation or in other places around the world. Yet antisemitism is growing. (So, too, is Islamophobia—for other reasons, relating both to the Middle East and to other factors. It is equally unacceptable.)

So to the specific context of the passage from 2 Cor. Paul, of course, was a Jew; he writes that he was “circumcised on the eighth day, a member of the people of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews” (Phil 3:5) and boast that “I advanced in Judaism beyond many among my people of the same age, for I was far more zealous for the traditions of my ancestors” (Gal 1:14). Luke reports him as telling Jews in Jerusalem that “I am a Jew, born in Tarsus in Cilicia, but brought up in this city at the feet of Gamaliel, educated strictly according to our ancestral law, being zealous for God, just as all of you are today” (Acts 22:3).

Paul’s writings and his faith are permeated with his Jewish heritage; in almost every letter he quotes Hebrew Scripture and the argument in his most significant letter, to the Romans, is grounded in a prophetic verse from scripture (Hab 2:4a, cited at Rom 1:17b). He is able to declare that “the law [Torah] is holy, and the commandment is holy and just and good” (Rom 7:12) and in great anguish he writes, “my heart’s desire and prayer to God for them [i.e. Israel] is that they may be saved”, noting that “they have a zeal for God” (Rom 10:1–2).

Yet each time he affirms his Jewish heritage and the faith of his fellow Jews, he places a critical comment against this affirmation. Of his own heritage and upbringing, “I regard everything as loss … I regard them as rubbish” (Phil 3:8; the translation of the last word is a very polite rendering of a crass swear word). Of the law, he says “I was once alive apart from the law, but when the commandment came, sin revived and I died, and the very commandment that promised life proved to be death to me” (Rom 7:9).

Of the fate of Israel, a “disobedient and contrary people” (Rom 10:21, citing Isa 65:2), he declares, “Israel failed to obtain what it was seeking; the elect obtained it, but the rest were hardened” (Rom11:7)—and yet, “they have now been disobedient in order that, by the mercy shown to you, they too may now receive mercy” (Rom 11:31). There is a glimmer of hope.

Yet still his rhetoric can be violently abusive: “beware of the dogs, beware of the evil workers, beware of those who mutilate the flesh!” (Phnil 3:2, referring to circumcision); and “anyone proclaims to you a gospel contrary to what you received, let that one be accursed!” (Gal 1:9); and even, “the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out; they displease God and oppose everyone … they have constantly been filling up the measure of their sins; but God’s wrath has overtaken them at last” (1 Thess 2:14–16).

Paul is nothing if not polemical in his letters. And as a Jew, when he writes such criticisms of other Jews, we cannot describe him as being antisemitic; rather, he is being critical of those who hold to Jewish traditions and resist adapting to the changes and modifications that the good news brings. We have seen Paul use this kind of polemical argumentation in other letters, when he uses stridently aggressive statements to articulate his opposition to a view. (Look at Gal 3:1–14, or parts of 2 Cor 10–13, or Rom 5:12—6:23.)

Such polemic was used in ancient rhetoric to refine and develop an understanding of a matter; the back-and-forth of the argument serves to sift and sort ideas, so that the kernel that remains at the end can be rigorously held. Paul knew this style of argument, and used it to good effect in his letters.

So when he writes disparagingly about Moses to the Corinthians, he is not being antisemitic, and we have no justification for using these words to criticize and attack Jewish ideas, or even Jewish people. Paul is using the techniques of his day to argue a point. We should not extract his words from their context and use them to validate criticisms of “all Jews” or of Judaism per se. What he says should be used with care and respect.

As we read on beyond 2 Cor 3:12–4:2, we find Paul writing about the transformation that takes place “from one degree of glory to another” (3:18), explaining that “this extraordinary power belongs to God and does not come from us” (4:7). It results in “an eternal weight of glory beyond all measure” (4:17), such that “we regard no one from a human point of view” (5:16). It is, in the end, “the God who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (4:6).

So Paul concludes this extended message of hope about this promised glory with a reminder that God has “reconciled us to himself through Christ”, and accordingly God “has given us the ministry of reconciliation” (2 Cor 5:18). It is in this spirit that we should reflect on the passage proposed by the lectionary for this Transfiguration Sunday.

For more on glory in Paul and elsewhere in scripture, see