For the Hebrew Scripture passage this coming Sunday, the lectionary offers a controversial passage (2 Sam 1:1, 17–27). The controversy revolves around the nature of the relationship between David and Jonathan. That relationship has an interesting history, and comes to a full expression in this passage.

In recent decades, a critical question that has been the focus of interpretation of the relationship between Jonathan and David has been, was this a loving same-gender relationship? Quite a number of scholars have argued that this was, indeed, the case.

Of course, more conservative and fundamentalist interpreters steadfastly refute this. They offer a number of arguments in support of their claims. The way that Jonathan’s love for David (1 Sam 18:3; 20:17) and the way that David describes his love for Jonathan (2 Sam 1:26) did not have sexual connotations, they claim. Alongside this, David is never said to have “known” Jonathan, which is a way that sexual intercourse is elsewhere described (Gen 4:1, 17, 25; 1 Sam 1:19).

These conservative scholars do not see the forming of a covenant (1 Sam 18:3) as signalling a loving relationship, as it was a political mechanism, as we noted in the previous blog on this passage. They claim that the “knitting” or “binding” of Jonathan’s soul to David (1 Sam 18:1) was more akin to the love of a father for his son; they also claim that Jonathan’s shedding of his clothes (1 Sam 18:4) was not in order to make love, but done as a political gesture.

However, I think that such arguments swim against the strong current that flows through the story of Jonathan and David. Writing thirty years ago, the biblical scholars Danna Nolan Fewell and David M. Gunn observed that “few commentators afford serious consideration to reading a homosexual dimension in the story of David and Jonathan”.

Fewell and Gunn note that “this is hardly surprising, given that until recently, most have been writing out of a strongly homophobic tradition… [but] far from stretching probability, a homosexual reading … finds many anchor points in the text.” (Fewell and Gunn, Gender, Power and Promise: The Subject of the Bible’s First Story [Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993], 148-49.) we need to explore this claim in more detail.

The key feature of the relationship that is anchored in the text is conveyed in the word אַהֲבָה (ahabah), which is translated “love”. It is a word which appears 40 times throughout the Hebrew Scriptures, describing the relationship that God has with Israel (Deut 7:8; 1 Ki 10:9; 2 Chron 2:11; 9:8), as well as that between husband and wife (Prov 5:19; Eccl 9:9), and most specifically the sexually-passionate love expressed in the Song of Songs (Song 2:5–7; 3:5, 10). In these latter places, there are strong romantic and sexual dimensions to its meaning.

Certainly, love defines the relationship between Jonathan and David; the word is used three times in this regard, as we have noted above (1 Sam 18:3; 20:17; 2 Sam 1:26 ). Joel Baden, in a fine article “Understanding David and Jonathan”, notes that “over and over again we are told that Jonathan loved David”. He observes that while the most common sense of the term is “a non-romantic meaning of ‘covenant loyalty’ … the use of the word in the case of Jonathan seems to go beyond that.”

Baden lists the accumulation of evidence in a series of key verses. First, “Jonathan does not just ‘love’ David. ‘Jonathan’s soul became bound up with the soul of David’ (18:1).

Second, when we read that “Jonathan ‘delighted greatly in David’ (19:1)”, Baden notes that “the same Hebrew word used in Genesis to describe Shechem’s desire for Jacob’s daughter Dinah (Gen 34:19).”

Third, Baden observes that when Jonathan dies, “David laments for him in these words: ‘More wonderful was your love for me than the love of women’ (2 Sam 1:26)”. That is a very strong statement indeed; as Baden notes, “the comparison to the love of women can hardly have a political valence; this is as close to an expression of romantic attachment between two men as we find in the Bible.”

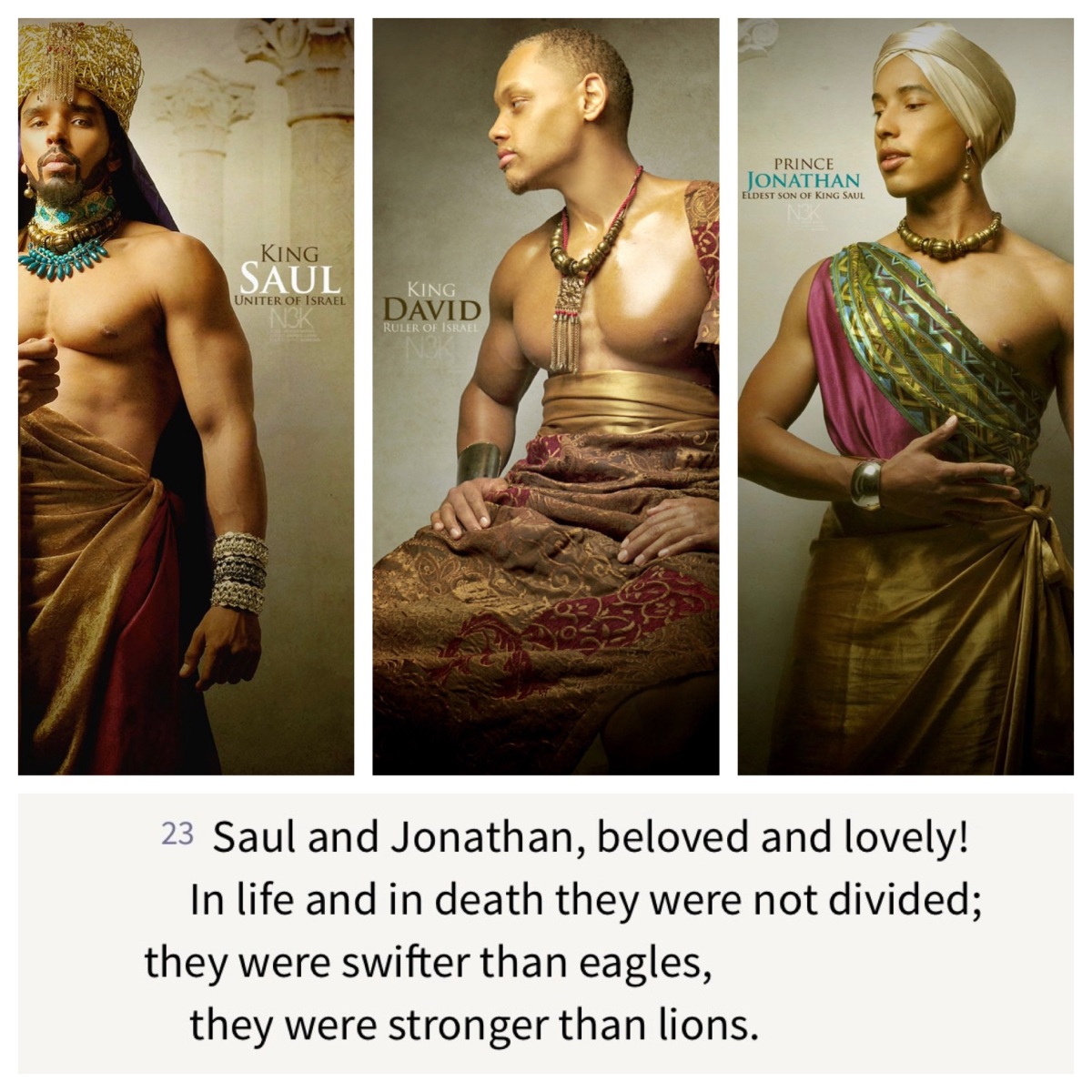

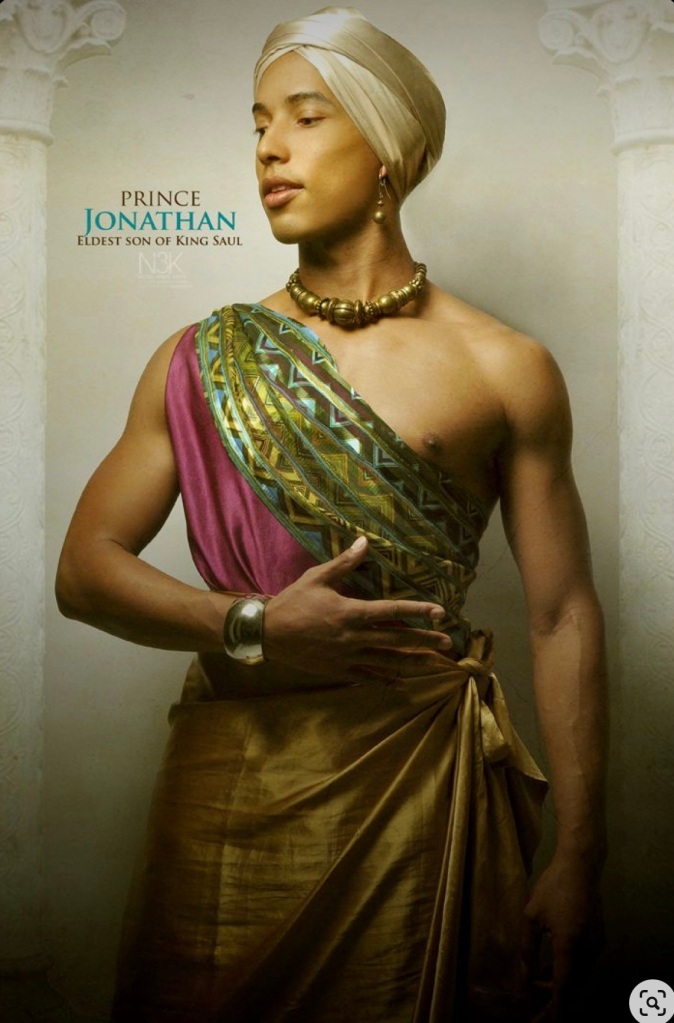

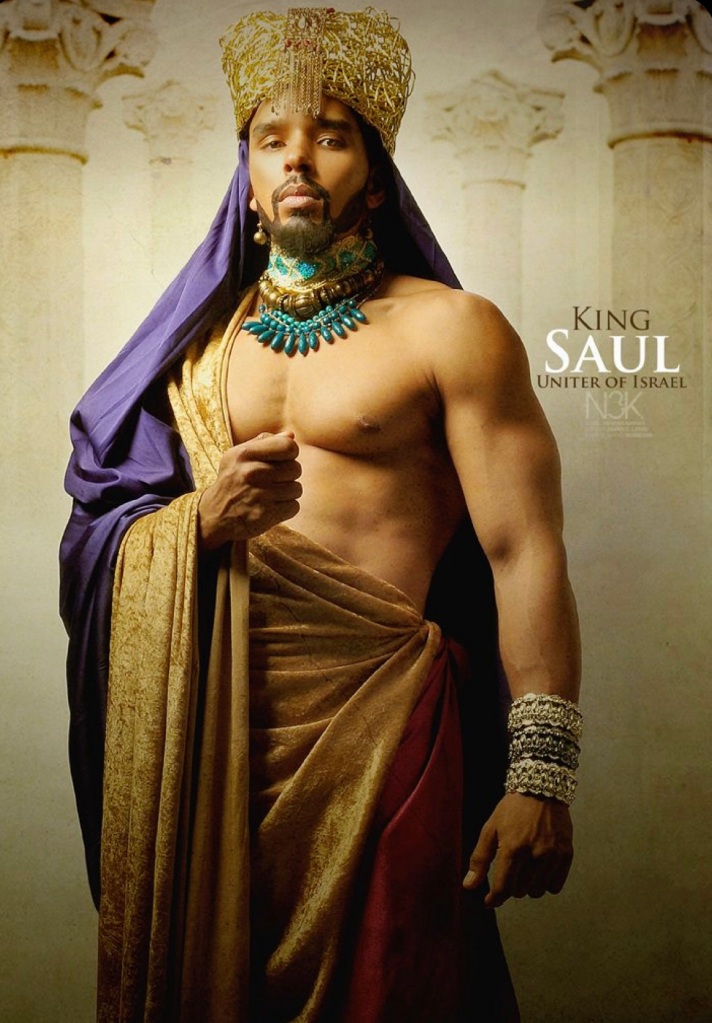

by photographer James C. Lewis

Indeed, we might reflect more on David’s comparison of Jonathan’s love for him with the love of women for him. Remember, he had no less than eight wives, who bore him at least eighteen children! So David knew a lot, we might assume about “the love of women”. It is worth pondering the comparisons that are drawn between the way that David experienced his living relationship with Jonathan, and his relationship with his first wife, Michal, whom he had married soon after he had entered into the covenant with Jonathan (1 Sam 18:20–27)—thereby incurring the wrath of Saul (18:28–29). I will explore this in a subsequent blog.

For the full discussion by Baden, see https://bibleinterp.arizona.edu/articles/2013/12/bad378027

*****

I think there are two important factors to consider as we think further about the relationship that David had with Jonathan. The first has to do with the function of the Jonathan—David relationship in the whole Samuel—Kings narrative. The second has to do without understanding of same gender sexual attraction.

With regard to the first matter: is it satisfactory simply to read the story of David and Jonathan as entirely political? Or, by contrast, as entirely personal? In a fine recent article, Nila Hiraeth offers a thoughtful and detailed consideration of the issues, drawing on a range of recent scholarly discussions of the story of David and Jonathan.

See https://thecooperativehub.com/the-opinions/the-opinions/jonathan-s-love-and-david-s-lament-part-3

Hiraeth proposes that the whole Samuel tradition (from his birth at 1 Sam 1 through to his death at 1 Sam 25) “has something to say about post exilic attitudes toward Israel’s transition to monarchy; specifically, a whispering undercurrent weighs the human cost of political pursuits and power-plays”. That is, the whole narrative has a politico-religious edge to it; the particular relationships within the narrative each contribute to that overarching purpose.

Hiraeth therefore does not discount the political dimension of the David—Jonathan relationship; she maintains that it is indeed present, but considers that this does not override the personal dimension of the story. In other words, it is not a binary, either-or, black-or-white scenario. Both political and personal aspects are integral to the story. “In Jonathan’s love we find personal attachment overlaid with political consequence”, she writes, and “in David’s lament we find political gain overlaid with personal loss”.

In terms of what this means, then, for a “queer reading” of the story of David and Jonathan, Hiraeth proposes that the story addresses the age-old tension between love and power. She notes that “the ultimate example for the prioritizing of the personal over the political in the David-Jonathan material is Jonathan, who chooses love over power. The text goes on to suggest that such an ordering of priorities can save lives, bestow dignity, shame kings into right action and move gods to mercy. Beauty for ashes; the government of heaven.”

And so, she concludes that “the David-Jonathan material of the Samuel tradition speaks most helpfully to contemporary discussions around Scripture and sexual identity, where the saving of lives and the bestowing of dignity are central concerns, and where the Christian traditions’ prioritising of power over love continues to carry a terrible human cost.”

David and Jonathan. “La Somme le Roi”, AD 1290;

French illuminated ms (detail); British Museum

A second factor that is important to consider in reading this story—as, indeed, with every story within these ancient narratives that includes elements of same gender attraction or activity—is to recognise the significant difference between ancient understandings and contemporary conceptions of sexual identity and attraction. We need to take care with how we use the terms “homosexual” and “heterosexual”. What we today understand by these terms is, most likely, not what the ancient thought about sexual identity and attraction.

Hiraeth observes that “the Bible clearly presupposes certain attitudes about sex and gender that are rooted in the socio-sexual mores of the ancient Mediterranean world and are foreign to the views likely to be defended openly by most adherents of Christianity and Judaism.” In undertaking a thorough and detailed literary-critical analysis of the texts, Hiraeth observes that “the privileging of a political or theological-political reading of Jonathan’s love over and against a personal and potentially erotic and/or sexual reading arguably has less to do with the text itself and more to do with the imposition of heteronormative values upon the text.” See https://thecooperativehub.com/the-opinions/the-opinions/jonathan-s-love-and-david-s-lament-part-3

The most detailed and helpful recent scholarly work that has been done with regard to ancient and modern conceptualisings of sexuality has been the research of Prof. Bill Loader, who over the past decade has published a number of full-length books as well as more focussed articles. See https://billloader.com

https://billloader.com

Prof. Loader has stated an important principle of interpretation when it comes to dealing with “homosexuality” in the Bible. He notes that biblical texts reflect a worldview quite different from what contemporary scientific research reveals. He proposes that “we need to respect what these texts are and neither read into them our modern scientific understandings nor for dogmatic reasons assert that they are inerrant or adequate accounts of reality.” See https://www.billloader.com/LoaderSameSex.pdf

Citing the matter that generated great controversy in the 19th century—evolution—he observes that “mostly we have no hesitation in recognising the distance between our understandings and theirs [in antiquity] about creation’s age and evolution”. So when we think about sexuality and gender, it should be possible that just as “new information enables us to see that creation is much older and complex”, so we can see that “reducing humankind to simply male and female in an exclusive sense and denying the fact that the matter is much more complex and includes variation and fluidity, at least around the edges, or suggesting this all changed with the first human sin, is inadequate.”

In other words, when we today recognise that people can quite readily identify as “gay” or “lesbian” or “bisexual” or “asexual”, we are a world away from the ancient world in which the biblical texts were written, in which it was assumed that all people were heterosexual but some took part from time to time in sexual activity with people of the same gender. That is radically different from the committed, loving, lifelong same gender relationships that we know exist in the world today.

Prof. Loader has made available his research in an accessible series of short studies, at https://billloader.com/SexualityStudies.pdf

So let us read this passage recounting David’s love for Saul and particularly Jonathan with care. Let’s not “assume” what we think is the reality; let’s not “condemn” what we find abhorrent; let’s not “dismiss” what does not align with our personal commitments. Let’s be open to the strong possibility that the relationship between David and Jonathan was a mutually-fulfilling, deeply personal, committed and loving relationship between two adult men who had a deep-seated attraction to one another. It’s a passage that challenges us in multiple ways!

*****

For part one, see