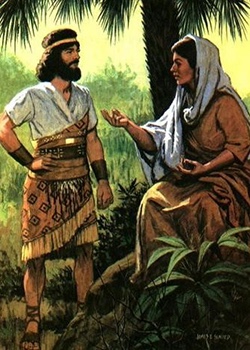

“At that time, Deborah, a prophet*, wife of Lappidoth, was judging Israel. She used to sit under the palm of Deborah between Ramah and Bethel in the hill country of Ephraim; and the Israelites came up to her for judgment.” (Judg 4:4–5).

[* Most translations use the feminine ‘prophetess’ here, as the Hebrew is nebiah, the feminine form of nabi, ‘prophet’. However, the key point is not her gender, but the role she fulfils, so I have followed the recently Updated Edition of the NRSV in using the generic term ‘prophet’ here to highlight that point. At any rate, the very next phrase, ‘wife of Lappidoth’, clearly indicates her gender.]

After the death of Joshua, the narrative reports that “the Israelites did what was evil in the sight of the Lord and worshiped the Baals; and they abandoned the Lord, the God of their ancestors, who had brought them out of the land of Egypt; they followed other gods, from among the gods of the peoples who were all around them, and bowed down to them; and they provoked the Lord to anger” (Judg 2:11–12).

In this context, God decided to “deliver them out of the power of those who plundered them” (Judg 2:16). So the book of Judges tells of a string of judges, men who worked hard to recall the people to their covenant with the Lord God: Othniel (3:9), Ehud (3:15), Shamgar (3:31), an unnamed prophet (6:8), Gideon (6:11–18), Tola (10:1), Jair (10:3), Jephthah (11:1; 12:7), Ibzan, Elon, and Abdon (12:8–15), and Samson (13:24–25; 16:28–31).

from the Icons of the Bible collection by James C. Lewis

The chapters of Judges maintain that these men, chosen to be judges over Israel, mostly exemplified good, positive qualities—although the story told of Samson, in particular, might cause us to question this assessment! The text declares that the spirit of the Lord came upon Othniel (2:10), as well as Gideon (6:34), Jephthah (11:29), and Samson (14:6, 19; 15:14). Othniel was called a deliverer (3:9), as were Ehud (3:15) and Shamgar (3:31), and Gideon was commissioned to deliver Israel (6:14–16, 36–38), as were Tola (10:1) and Samson (13:2–5). Led by the spirit, called to be a deliverer: these are qualities that Christians read about in the story of Jesus, many centuries later.

The impact of the efforts of these various judges was merely transitory; the people returned again and again to their sinful, idolatrous ways. “The Israelites did what was evil in the sight of the Lord” (initially at 2:11, repeated at 3:7) is a recurring refrain throughout the book of Judges. It signals that the people reverted to their evil ways after Othniel (3:12), Shamgar (4:1), Deborah (6:1), Jair (9:6), and Abdon (13:1). As a result, we are told that the people were “given into the hands” of their enemies on each of these occasions (3:8; 4:2; 6:1, 13; 10:7; 13:1).

Beyond these summary statements, in the final chapters of the book, details are given of the evil deeds of the mother of Micah, who made an idol of cast metal (17:1–6); the men of Gibeah, who raped the Levite’s concubine (19:22–25); the Levite himself, who cut his concubine into twelve pieces (19:27–30); and then the attacks on the Bejaminites by the other tribes of Israel (20:1–48). The book draws to its end with the mournful conclusion, “in those days there was no king in Israel; all the people did what was right in their own eyes” (21:25).

So many good leaders; so many evil deeds; so little progress over the four centuries covered by the stories told in the book of Judges. The pattern is relentless (see 2:18–20): first, “the Lord raised up judges for them, the Lord was with the judge, and he delivered them from the hand of their enemies all the days of the judge” (2:18). The explanation for this rests with God: “the Lord would be moved to pity by their groaning because of those who persecuted and oppressed them” (2:18).

However, this did not last: “whenever the judge died, they would relapse and behave worse than their ancestors, following other gods, worshiping them and bowing down to them” (2:19). So “the anger of the Lord was kindled against Israel” (2:20) and the cycle repeated. The pattern adheres to the typical Deuteronomic view, that God blesses those who “fully obey the Lord your God and carefully follow all his commands” (Deut 28:1) and curses those who “do not obey the Lord your God and do not carefully follow all his commands and decrees” (Deut 28:15).

from the Icons of the Bible collection by James C. Lewis

Amidst this string of male judges, Deborah stands out. She is, of course, the only female amongst the list of male judges noted in this book. That makes her quite exceptional—she stands alongside Sarah, Miriam, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah, and Esther as one of the seven female prophets in Israel. Whilst stories approving of the leadership of some of those male judges are told (notably, of Gideon and Samson), much more is said of the female judge Deborah.

For a start, no other judge is accorded a long poetic song celebrating their achievements; Deborah is (5:1–31), as she joins with Barak son of Abinoam to “make melody to the Lord, the God of Israel” (5:3) and celebrate that “the earth trembled, and the heavens poured, the clouds indeed poured water, the mountains quaked before the Lord, the One of Sinai, before the Lord, the God of Israel” (5:4–5), when “you arose, Deborah, arose as a mother in Israel” (5:7).

My wife, Elizabeth Raine, has researched Deborah’s story, and tells me that it is believed that the Song of Deborah (and Barak) is modelled on the Song of Miriam (and Moses) reported as the fleeing Israelites reached safety on the other side of the Sea of Reeds. There, a short song attributed to Miriam (Exod 15:20–21) is linked with a longer song, attributed to Moses, which has the same opening line (Exod 15:1–19; see especially verse 1).

As all the tribes gathered (5:14–18), Deborah and Barak sing of Jael: “most blessed of women be Jael, the wife of Heber the Kenite, of tent-dwelling women most blessed” (5:24), and tell of when Sisera asked for water, “she gave him milk, she brought him curds in a lordly bowl” (5:25), before recounting in gruesome detail, “[she] put her hand to the tent peg and her right hand to the workmen’s mallet; she struck Sisera a blow, she crushed his head, she shattered and pierced his temple” (5:26).

What follows is sung in stark simplicity: “he sank, he fell, he lay still at her feet; at her feet he sank, he fell; where he sank, there he fell dead” (5:27)—and then, in a powerful conclusion, “the mother of Sisera gazed through the lattice”, asking the poignant questions, “Why is his chariot so long in coming? Why tarry the hoofbeats of his chariots?” (5:28).

Then—as we hear at the end of the rule of some of the other judges in this book—“the land had rest forty years” (5:31; see also 3:11, 30; 8:28). It is a stark contrast to the tumult of the battle just recounted.

A second distinctive feature about Deborah is that she is the one judge in this book who is described as making legal judgments (4:4–5). She sat under the tree which later bore her name, “the palm of Deborah, between Ramah and Bethel in the hill country of Ephraim”; there, “the Israelites came up to her for judgment” (4:5). It is this brief note about her role that later is used in the phrase “palm tree justice”, referring to “ad hoc legal decision-making, the judge metaphorically sitting under a tree to make rulings based on common sense rather than legal principles or rules” (Oxford Reference, an online resource from OUP).

Even though the book bears the name Judges, almost all the key characters in the book are not described using this word. The early mention of judges indicates their role in the society of the day (2:16–18); yet later in the book, Jephthah informs the King of the Ammonites that he will not enact judgement; “let the Lord, who is judge, decide today for the Israelites or for the Ammonites” (11:27). The term “judging” is used only of Deborah (4:4)—she is the only person, apart from God, who makes any “judgement” (4:5). The figures whom we regularly describe as judges are actually presented in this book, as we have seen, as deliverers, guided by the Spirit. It is because of the programmatic statement of 2:16–18 that we consider them to be judges.

But it is only Deborah who sits under the palm tree to judge. The palm tree, known for its fruit in Israel (Ps 92:12; Song of Songs 7:7–8; Ezek 41:18–19; Joel 1:12), is one of the trees utilised by Wisdom when she later declares, “I grew tall like a cedar in Lebanon, and like a cypress on the heights of Hermon; I grew tall like a palm tree in En-gedi, and like rosebushes in Jericho; like a fair olive tree in the field, and like a plane tree beside water I grew tall” (Sir 24:13–14), before she extends the invitation, “come to me, you who desire me, and eat your fill of my fruits; for the memory of me is sweeter than honey, and the possession of me sweeter than the honeycomb” (Sir 24:19–20).

A third feature of Deborah is that she did not herself engage directly in armed battle with those living in the land of Canaan. Others who led Israel in this period willingly engaged directly in such battles. Othniel “went out to war, and the Lord gave King Cushan-rishathaim of Aram into his hand” (2:10). Ehud, a left-handed man, “made for himself a sword with two edges, a cubit in length; and he fastened it on his right thigh under his clothes” and then, at an opportune time, he killed King Eglon of Moab (3:16–22).

Of Shamgar, it is noted quite succinctly that he “killed six hundred of the Philistines with an oxgoad” (3:31), whilst Gideon’s successful campaign against the Midianites is narrated in quite some detail (6:7—8:21) and Samson’s conflict with the Philistines also receives detailed attention, culminating in the moment at Lehi when “he found a fresh jawbone of a donkey, reached down and took it, and with it he killed a thousand men” (15:1–15).

Whilst Deborah did instruct Barak, of the tribe of Naphtali, to take up a position on Mount Talbot and prepare to do battle (4:6–7) and, whilst she did travel up Mount Tabor with him and his men (4:8–10), she did not take part in the battle that ensued. Deborah sent Barak and his ten thousand warriors down to engage and defeat the Canaanites under Sisera (4:14).

In a scene that was reminiscent of the time when “all of Pharaoh’s horses, chariots, and chariot drivers” were “ thrown into panic” at the sea of reeds (Exod 14:23–24), we learn that “the Lord threw Sisera and all his chariots and all his army into a panic before Barak; Sisera got down from his chariot and fled away on foot, while Barak pursued the chariots and the army to Harosheth-ha-goiim” (Judg 4:15–16).

The rout was complete, placing Deborah and Barak in the same category as Moses, effecting a complete and total defeat of the enemy. “All the army of Sisera fell by the sword”, we are told; “no one was left” (4:16). The gory end of Sisera, impaled with a tent peg in his skull (4:22) completes the saga of Deborah; this deed was performed by another powerful woman, Jael wife of Heber the Kenite (4:17–21), who is celebrated in the song of Deborah and Barak (5:24–31).

And so the people of ancient faith remember their even older ancestor, Deborah: prophet, judge, warrior, “a mother in Israel”.